Some tips for getting art writers to notice your work. Hint: a cow’s tongue probably will not do the trick.

It’s the dream of every artist to be noticed by a prestige critic, like Roberta Smith or Jerry Saltz or any other of the noteworthy art scribes in urban areas. If you are not with a blue-chip gallery or a name commodity in the art world, it’s a long shot but worth even the risk of an out-and-out pan (as Oscar Wilde remarked: “The only thing worse than being talked about, is not being talked about”). With the right moves and much patience, you can woo writers into your lair for a studio visit or spark enough interest to follow you. Below, six critics and art journalists (sometimes there’s not much distinction) reveal what captures their attention.

Franklin Einspruch: Before speaking to how to get a critic to pay attention to your work, let’s ponder whether and why. The days of the influential critic are over. They were the product of a much smaller art world, in a time before the periodicals were eviscerated. It was also a time when fine art was a common cultural touchstone. Williams art historian Michael J. Lewis dates the beginning of the end to 1990, when the American public, prompted by the hearings around the NEA Four, “drew the fatal conclusion that contemporary art had nothing to offer them. Fatal, because the moment the public disengages itself collectively from art, even to refrain from criticizing it, art becomes irrelevant.”

If you merely want to be written about, target the art reporters rather than the art critics. The former are more numerous, and they have more opportunities to write. (Obviously, the critics and the reporters are often the same people.) The feature writer’s main need is what we scriveners call an “angle.” Some poor sap has to convince his editor to let him turn your story into 800 words of copy. If you’re not sure what your story is, enlist the services of an arts marketer to help you form one. Without it, your press release—the next step—is sunk. A certain kind of person can make art with the press release in mind. Whether and to what degree that is appropriate is an exercise left to the reader. I’ll say, though, that as a critic, I can smell a lack of integrity like a Rottweiler can smell fear.

If your goal is not merely to be written about, but to have a genuine creative and intellectual exchange with someone whose judgment you respect, you need only approach the critic with the regard and good faith that you would like the critic to approach you. I do a fair number of studio visits, some of which I arrange, some of which the artists arrange. I often accept offers from artists to meet them at their shows, if they have one up. This goes better if the artist has some idea of where I’m coming from as a critic, but not too much of one, because my tastes are unpredictable and I may surprise you.

Also, your goal should not be to get me to review your current show or your current body of work, but to see it in preparation for your next one, or the one after. I may indeed write about the current one, but time and opportunity often run short. Rather, the idea is that we form some mutual knowledge and respect over a stretch of time, and then our work lives cross one day and I’m available to review your show or write your catalogue or curate you into an exhibition or whatever it is, and I can put something together because I have a sense of your trajectory.

You may not care to bother with any of this. If not, I wouldn’t blame you, and you should just keep making your art. I can’t promise to do anything for you, even if I try. But if I look at your art I will see it to the utter extent of my power to see anything.

Franklin Einspruch is an artist and the editor of Delicious Line (well worth a look if you’d like to write about art yourself). He also contributes regularly to The New Criterion.

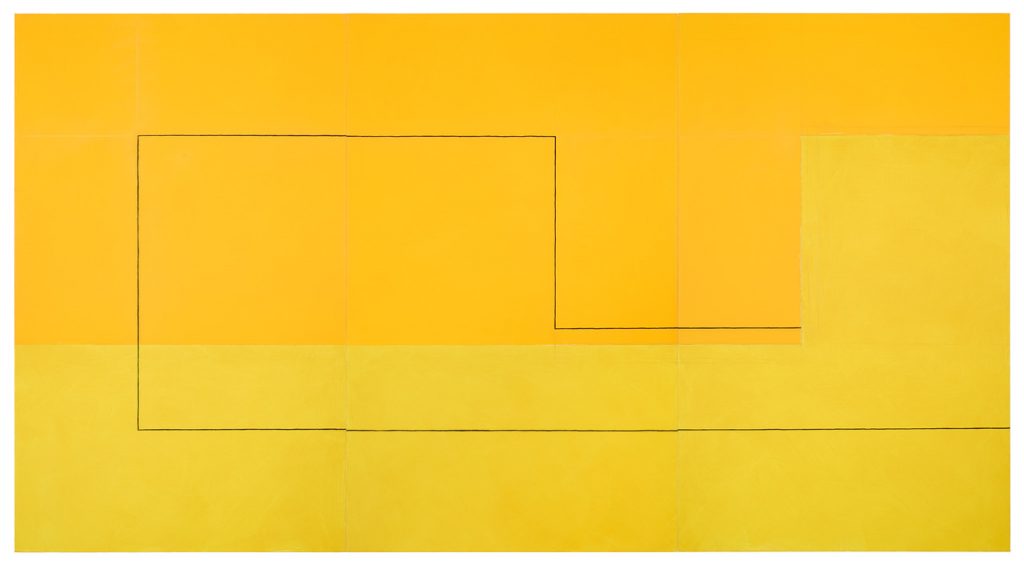

Jan Cunningham’s Yellow Triptych (2018, oil on linen, 60 by 111 inches) caught critic Karen Wilkin’s eye

Karen Wilkin: In my experience, an introduction from someone the critic knows and respects makes all the difference. Like many other things, the personal connection is invaluable. I try to see group shows organized or juried by people whose eyes I trust, where I sometimes make discoveries, but in the interest of self-preservation, I ignore unsolicited or unsupported requests that I see shows or otherwise pay attention. When an artist I’m interested in suggests something, I respond to that, sometimes to my benefit. Robert Taplin, whose work and writing I’ve followed for years, with enthusiasm, recently suggested I see a show by Jan Cunningham, a painter whose work I didn’t know. Turns out she makes subtle, inventively colored geometric abstractions that play different kinds of drawing against the memory of a grid. I’m very grateful to Robert for alerting me to her work and I hope to see more in the future. Other occasions have been less rewarding, such as when I recently participated in one of David Cohen’s review panels and, in preparation for the discussion, trekked to a gallery in the wilds of Brooklyn, open only on weekends (probably only when the wind is from the southeast), to see a pretentious installation by someone I was unfamiliar with and hope to remain unfamiliar with. Luckily, I didn’t have to meet him.

Karen Wilkin is a New York-based critic, curator, and teacher, who writes regularly for The Wall Street Journal, The Hudson Review, and The New Criterion. You can find out more by listening to the podcast interview here.

Jonathan Goodman: Given that there are far too many artists in the art world today, and far too few art writers to pay attention, the problem of catching a writer’s eye has become much larger and more difficult than before. My following advice is based on decades of experience, but success is anecdotal—we can only proceed on the very limited basis of our experiences. The best thing to do, I imagine, is to make as much social contact with writers as possible, and if there is some connection between you (the artist) and the critic, then it makes sense to swiftly pursue the relationship. The idea, of course, is to have the writer come to the studio and, hopefully, write a piece in favor of the artist’s work. To give a particular example, I met the upstate New York sculptor Millicent Young at a reading I was giving; we hit it off, and in light of our warm communication, I decided to do a studio visit with her. I liked her work, and was able to work up a successful interview with her for Sculpture magazine, as well as write a review of her recent show at Cross Contemporary for WhiteHot, a New York-based Internet blog.

But this doesn’t happen easily. Now, critics are very wary of being approached. My own experience has been that if I like an artist I meet, I usually like the work as well (but this is not always the case). The other practical stratagem is to invite critics to your show when you have one, although the New York art world is swamped with such events, and even if the critic is well intentioned, he or she may not be able to come to the show. The emphasis has to be directed toward personal contact. Some writers are more adventurous than others and are willing to take chances—such as traveling a good distance to a studio or an opening, or supporting someone with almost no previous recognition. But many won’t do this, and so it is a long, slow, uphill battle to connect with those whose writing might make a difference in an artist’s career.

To summarize: the number of artists has become so large as to break down normal relations and contact between them and the writer. There is not too much that can be done about this, but it makes sense to connect personally, without immediately demanding professional interest, with a writer who you want to know better. Writers are people too, and do not appreciate a heavy sell. On the other hand, writers today often have more power than they should, given the fact that they are less numerous than the many, many artists they may be writing about. My final advice is to work steadily, not to take anything personally that smacks of rejection, and to slowly cultivate relations with the professional whose help is needed. Remember, we are in this for the long run, not for the immediate spark.

Jonathan Goodman is a regular contributor to WhiteHot, The Brooklyn Rail, Sculpture, and publications in Madrid and Beijing.

Kim Levin: How to get a critic to pay attention to your work? Different people go about things differently, and what works for one artist may not work for another. Chance plays a large part. Serendipity. Luck. Do something you are comfortable with.

It was a very different world in the years I was making studio visits: people answered phones and sent letters and postcards in the 1980s; they sent faxes in the ‘90s.

I once got a phone call from an artist who had just moved to New York. He quoted something I wrote and we discussed it and I ended up making a studio visit to see his work.

On the other hand, I once got a phone call at 1 a.m. on a Saturday from a quite drunk artist, well-known in the Pattern and Decoration movement. He said: “You called my work ‘decorative.’ What the hell did you mean by that?”

Another time, I got a call from Richard Prince, who demanded to know why I had referred to the work of Sherrie Levine as “re-photography.” He claimed to own the word “re-photography.” He told me: “That is my word,” a ridiculous claim from an artist known for his appropriation art. Another artist sent me a cow’s tongue as an announcement for a show, which, since I was traveling, sat in the hall rotting and almost got me evicted. Not the best idea. It’s impossible to forget things like that. So my first advice is to be polite: Don’t hand out announcements for your show at other artist’s openings or in elevators. Don’t bombard a critic for years with news of your art if no interest has been shown in it.

And last, but not least, start by reading as many writings by different critics as you can. Pick a few whose work aligns with yours, whose writing deals with the same issues, whether in form or content or context—critics you feel some affinity with, or whose writing you relate to. And then, especially if you have an exhibition or a work on view, or if they have written something you appreciate, send a handwritten note and invitation with the information and, above all, with images. Or, since we’ve all become digital creatures now, send it by e-mail with a link.

Kim Levin is a former critic for The Village Voice and ARTnews. She is now at work on a book of essays.

David S. Rubin: For me, “a picture is worth a thousand words” has always worked at getting my attention. There was a time when, as a curator and critic, I would save illustrated exhibition mailers and organize them into thematic file folders. Now that we live in the digital age, I think an actual mail piece might stand out and garner a curator’s or critic’s attention. Today, of course, artists use email and social media such as Facebook and Instagram to get their work seen virtually. Email a link to your website along with an invitation to visit your studio. As with approaching a gallery, artists should target the writers they approach, so do your homework and seek out critics who have previously shown an interest the kind of work that you do. You might try friending them on Facebook or connecting on Linked-in if they have an account.. Yet to stand out from the mass emails that critics receive, look into self publishing something about your work in hard copy. I recently visited the studio of an artist who found an inexpensive online printer and produced a low cost but very nice-looking catalog on his work. See if you can get a mailing address and send something that your targeted writers can open in the mail and hold in their hands. If you have an exhibition on view, schedule a gallery talk and be sure to invite your targeted writers to attend.

David Rubin is a Los Angeles-based independent curator, artist, and writer. In addition to organizing a nationwide exhibition of the graphic works of Salvador Dalí, he is curator for Carole Sorell Inc. of “A Notational Guide to the Universe: Paintings by David ‘LEBO’ Le Batard,” which opens in June at the Bradbury Art Museum at Arkansas State University and will travel to other venues.

Sharon Butler: The best thing artists can do is read criticism and reviews. Too many artists want to have their shows reviewed, but never take the time to read criticism themselves. Through reading, artists will begin to understand what type of work each of the critics covers. Decide who is mostly likely to respond to your work and add them to your email list. If they are on Instagram, Twitter, or Facebook, follow them and comment on their posts. In short, start a conversation. Then, when you have a show, they might be more interested in seeing and writing about your work.

You can also raise your visibility by starting a project that creates opportunity for other artists and writers. Curate a show, do artist interviews for a local publication, start a salon. If you contribute in some way, people will be more interested in what you are doing, and, again, writers will be more interested in covering it.

But, most of all, make work that inspires discussion, opinion, argument. If you make the same boring thing year in and year out, no matter how well drawn or painted, there is nothing for critics to write about.

Sharon Butler is a New York-based painter and the founder and editor of Two Coats of Paint, a project that includes reviews, an artists’ residency, and interviews with artists. She is affiliated with the New York Academy of Art, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts and Parsons, The New School

Artist Millicent Young met critic Jonathan Goodman at a reading from his works. The rest was kismet.

As you’ve gathered from reading the above, a key component in snagging a writer’s attention is sociability and even likability. If you are represented by a gallery, you might convince your dealer to help bring critics into the mix. And this doesn’t have to be an expensive proposition. “Since I was operating on a shoestring, I would host a private dinner after the opening that I prepared myself earlier in the day,” says Jen Dragon, whose gallery, Cross Contemporary, just closed its doors in upstate New York. “After a couple of years, I moved the dinners to an Italian Restaurant across the street that could easily seat a large group of us together (and divide the check accordingly). But apart from the opening festivities, I would make a point of personally inviting an art writer to visit the show, and then I would treat them to lunch. This worked well as it gave me an opportunity to get to know the critic and find out more about them. Lastly, many art critics are also poets and/or published authors, so it made sense to host a reading of their work at the gallery. This helped expand the mission of the art gallery into a more cultural space.”

Remember that art writers are people too. We like to be wined and dined and wooed. But be wary of any “critic” who asks to be paid by you, the artist, for a review (a catalogue essay is another matter). Even if the fees are miserly, and they generally are, it’s the publication that pays. Not you. You have enough on your plate.

Ann Landi

Top: critics Roberta Smith and Jerry Saltz with artist Terry Ward in 2012 (photo, The Chelsea Reporter)

Ann, at the risk of redundant praise if there is such a thing – you’ve asked another important question and received a great range of insightful responses, the aggregate of which is illuminating and helpful in making sense of a topic… another fine colllage made of the questions you ask, your gifts as an art writer, and the amazing intelligence of the network you have made from the decades of your professionalism. Vasari21 is really maturing though I know how draining the work can be. I feel so fortunate to be included here in Jonathan Goodman’s part and to feel your support.

One more comment here of appreciation on two threads identified in the piece that bear emphasis – ones that are particularly salient for me, at least. One is the fact that art writers are poorly paid and many artists seem to have the assumption that their work is some form of public service that the artist is due. Indeed art writers are frequently artists themselves. Two is the notion of likeability – that consideration, empathy, generosity, gratitude matter, that its not about ‘you’ all the time.

Thank you so much for yet another informative and wonderful article. Thank you to the art critics and reporters that took the time to respond to Ann Landi about a topic that’s frequently on artists’ minds! I am a huge fan of Millicent Young’s work and enjoyed Jonathan Goodman’s article about her exhibit at Cross Contemporary. And am always grateful for all that Sharon Butler shares through Two Coats of Paint and her other endeavors. I apprecitaed the insight and advice offered by all those interviewed. As an artist, what I want most is to create intriguing unique and evocative work…and then for that work to find its audience. Not always an easy thing to do. I no more expect every art critic/reprter to respond to my work, than I expect for it to resonate with every viewer(though in a perfect world… :)) But getting some insight into how the process works is always helpful. Every time I read Vasari21 I find more artists, writers, critics, and artwork, to learn about, think on and investigate. Thank you!

Great reporting and writing, Ann. Thank you!

Thank you Ann and all those who contributed to this article. It’s always enlightening to look at a topic from another perspective.

Ann, Thanks for all this insight! Living in Montana means I have to seek every relationship. To enforce the ideas set forth here, I just wrote to a critic with a thoughtful response to her essay. She kindly replied. 🙂

Ann, I so appreciate that you continually give us access to the behind the scenes.

I have begun a conversation with three other mature artists here in the Bay Area focusing only many of the concerns and issues articulated by these selected Art Critics.

I appreciate the opinions and suggestions offered as a means for broadening strategies for making contact with the small numbers of thoughtful critics remaining who are available to Artists.