Talk about “Surrealism” in conversation with artists and art lovers you are most likely to think of works by Dalí, Magritte, Tanguy, Ernst, or possibly Paul Delvaux. Mention “American Surrealism,” and the terrain gets tricky. Didn’t Adolph Gottlieb, Mark Rothko, and Jackson Pollock all have their surrealist moments on the way to their more memorable achievements? And then try “female American surrealist,” and see if you can name anyone other than Dorothea Tanning who garnered significant attention in the last century.

So it’s small wonder that a painter like Peter Miller (1913-96) has slipped through the cracks of art history. There is the business of her first name, for example, which she adopted while still studying at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in the early 1930s—recognizing long before the Guerrilla Girls that work ostensibly by a man would be taken more seriously in the art world of her time. (She was born Henrietta Myers, and became Peter Miller after she married C. Earle Miller, a fellow student at PAFA and also an aspiring artist.)

Her obscurity might also be explained by a reluctance to promote herself in the New York art world—which was the art world in the United States as she was launching her career. Her eventual physical distance from that milieu was also not conducive to cultivating the right dealers and collectors. By 1935, she was dividing her time between a farm in Brandywine, PA, and a ranch in Espanola, NM, about half an hour north of Santa Fe (for a pair of young artists, the Millers seemed to have had considerable financial independence).

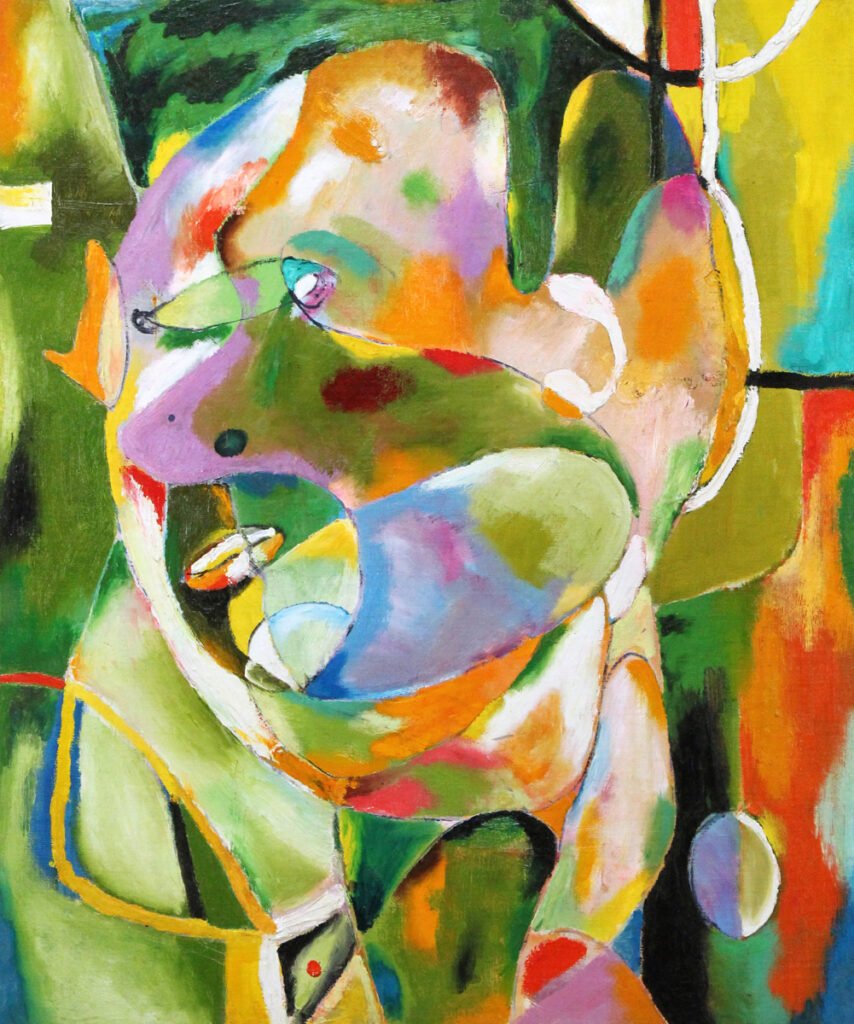

Nonetheless, Miller did show in New York, at the prestigious Julien Levy Gallery in the mid-1940s, and her first exhibition included a catalogue with an essay by Robert Goldwater—now probably better known as the husband of Louise Bourgeois, but in his day a pioneer art historian, the author of the groundbreaking Primitivism in Modern Art. Starting in 1935, the Millers made frequent trips to Europe, armed with letters of introduction from a former teacher to Picasso, Matisse, and Miró. Not surprisingly, echoes of those masters—along with Paul Klee—turn up in her canvases. But critics also noticed the influences of the Native Americans of the Southwest, which the Millers considered their spiritual home. In Espanola, they were neighbors of the Tewa Pueblo, “indigenous people whose crafts and religious beliefs fascinated her,” writes Francis Naumann in his catalogue essay for a show of her paintings at Peyton Wright in Santa Fe, NM, now at the gallery through November 15. “The reliance of Native Americans upon the land and the animals who occupied it permeated her work for the remaining years of her career.”

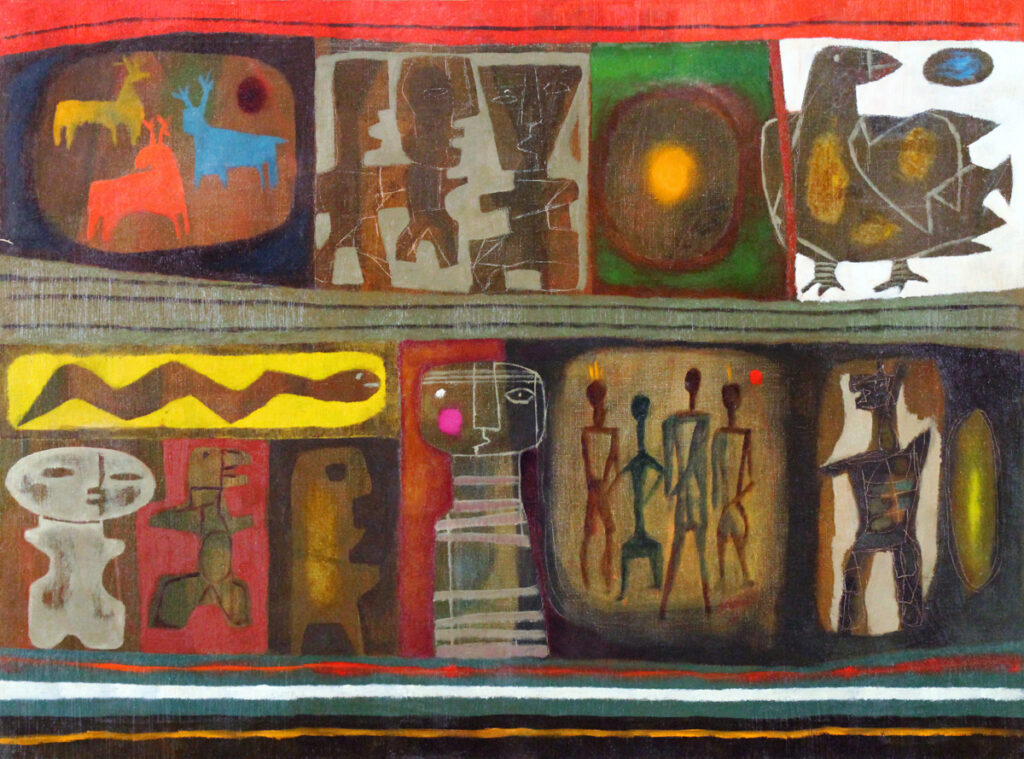

By the time of her second show at Julian Levy, the ethnic subject matter was even more pronounced. “The Indian symbols become a kind of vocabulary to be amalgamated with the sophisticated symbol-language of Miró and Klee,” noted an anonymous contemporary reviewer quoted in Nauman’s essay. “Especially salient is the lesson she has learned from Indian painting of relationships to shape in strange, undefined space.”

Throughout her long life, Miller’s imagery conjured with the symbols, pictographs, pottery, and other components of a culture then still so readily apparent in the Southwest (now it’s mostly reduced to jewelry and tchotchkes marketed to tourists). She absorbed the spiritual values of the Tewa and melded them with the Surrealist vein that throbs in her biomorphs and bright colors. As conservator Paul Gratz, who found a trove of Miller paintings from her estate, notes in the Peyton-Wright catalogue: “Miller’s technique was unique. In some of her paintings, she textured the ground to mimic canyon walls. In others, she used sgraffito and applied thin veils of color that she would then rub with cloth. One small area of the canvas can contain six to eight different colors….The compositions are deliberate, and she had a sophisticated knowledge of color. There are paintings within the painting, layers upon layers.”

She adopted as her personal totem the turtle. “There is no way to know for certain whether Peter selected the turtle herself or whether it was bestowed on her by the Tewa-speaking Pueblo Indians,” writes Bill Richards, an artist friend later in her life, in the Peyton-Wright catalogue. “My guess is that it was divined for her by a Tewa Shaman. She and Earle, a printmaker and sculptor, [maintained] a life-long relationship with the Pueblos, cherished for its depth of knowledge and friendship, including the adoption of Tilano (a Pueblo) and his partner Edith Warner (a Southwest writer originally from Philadelphia) as godparents and mentors.”

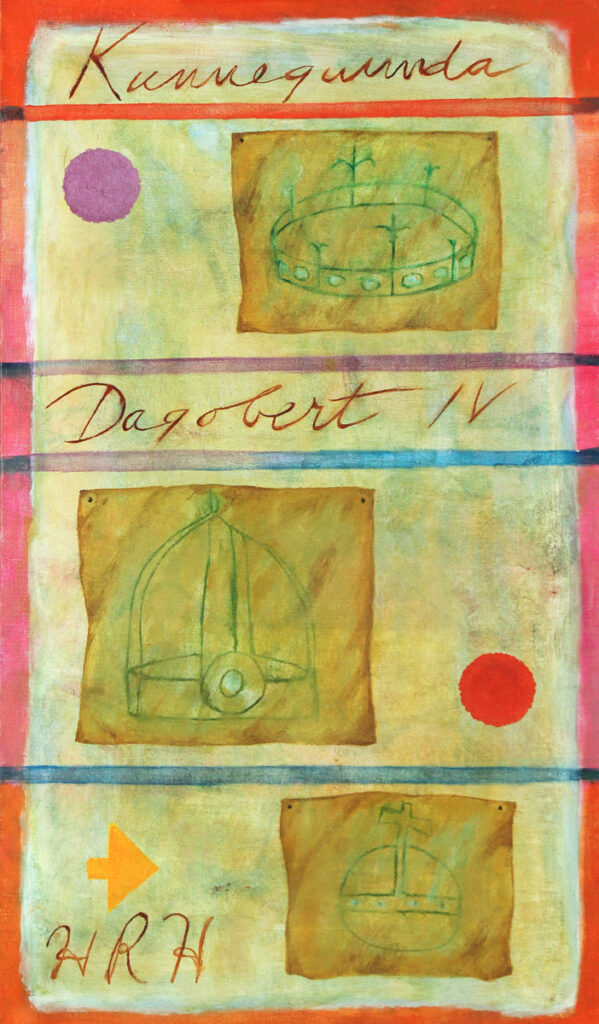

Old myths and prehistoric civilizations continued to fascinate her in her later years—“a number of her paintings from the 1960s and 1970s illustrate tools and various artifacts that appear to have been unearthed from an archaeological dig,” says Naumann. One painting Naumann studied closely seems to refer to the legend of a Polish princess, Kunegunda, who, to avoid marriage, set up a series of impossible tasks for all those who sought her hand. When one brave knight accomplished a tricky circuit along her castle’s walls on horseback, in armor, he rejected her. In despair, the princess jumped to her death. A strange subject for a woman steeped in Pueblo civilization, but other references make their way into her works—matadors and bullfights, symbols derived from Egyptian art and hieroglyphs, unidentified goddesses, and mysterious “bird women.”

Never much concerned with the pre-eminent movements of her mature years—Abstract Expressionism, Minimalism, Color Field painting—she adhered to a resolutely personal vision. One still sees the Miró-like shapes and the abstract geometric patterning of Paul Klee in her later works—so much so that if you looked at some, like Architectural Abstract from the 1960s, you might easily guess it was by Klee. But Miller never really feels derivative. Her voice remained her own—searching, fiercely individual, and both gentle and brave—throughout her life.

Top: Hawksnake (1950s), oil on canvas, 16 by 22 inches

This is a wonderful article, thank you for bringing light to Peter Miller and allowing her to have that voice of her own!