Suggestions for storing, selling, tossing, or giving away unwanted old work

One of the saddest days of my life was the day I carted all my youthful paintings from my parents’ summer house to the dump in Montauk, NY, after selling the property in 2003. These included a couple of fractured nudes made in high school, along with the Tondeleo, recently described in my confessions of a closet painter, works my mother proudly hung on the walls throughout the tiny two-bedroom retreat. Yes, the paintings, for me, were fraught with nostalgia, but of absolutely no value to anyone, and I was at the time living in a New York City apartment with minimal space for my clothes, let alone my adolescent efforts as an artist.

Tondeleo came to mind when Vasari21 member Diane di Bernardino Sanborn suggested a post for the site about what to do with excess inventory and proceeded to kickstart the process with a notice on Facebook asking for solutions. I followed up with some more inquiries, and the answers came rolling in. As I had already learned, it’s damned difficult simply to consign old work to the slag heap, even when you can’t see any need whatsoever to keep it around. But real artists can and often do look back on earlier efforts to pick up on old ideas or see what the journey has been all about, and so it’s worth keeping at least some of the work. And there’s always the chance a collector (or even a museum!) might want a work from one of your earlier periods.

Creative recycling: Diane Sanborn cut up and collaged pieces of an old painting to create a new work called Strategies, acrylic on board, 24 by 36 inches

So the first thing to do is to edit as ruthlessly as possible. If you can’t get friends or partners to help you weed out the chaff, ask a professional. “I’ve had three curators come to my studio at different times, and showed them all my inventory,” says Annell Livingston. “They were very good at helping me sort through the works I needed to eliminate.” She’s also hired a person to help her place her paintings with worthy organizations (like hospitals and nursing homes), where the pieces will be seen and perhaps offer comfort—but more on that later.

“If, upon looking back at the work with new eyes, it is not 100 percent up to my standards, I trash it,” says Hester Simpson. “If, however, it holds my interest in some mysterious way, I store it for the next go-round. The pieces that I love that have not sold in, say, ten years, I give to friends and family or hang in my home.

Ingenious Storage Solutions

No doubt you’ve already crammed every closet, spare bedroom, tool and garden sheds, garage shelves, and attics to the bursting point. But there are still other ways to minimize and maximize at the same time. One obvious one is to take older paintings off their stretchers and roll them together. “I keep adding to the roll until it gets too bulky and then start another roll,” says Barbara Cowlin. “I keep track of what’s in the roll just in case one of the paintings will fit a call for a show or is just right for a collector. Then I buy new stretcher bars and re-stretch. Meanwhile I re-use the old stretcher bars for new paintings.”

Barbara Kemp Cowlin with a roll of canvases and paintings under wraps in a storage closet at home in Oracle, AZ

Maureen Shea, for whom available space is even tighter than most, stacks unstretched canvases and pins them, as many as 10 deep, to the walls of her studio. “Most of these paintings are ‘in process’ in the sense that I want them within easy reach for revisiting, but generally when the stack gets too thick they start to fall, so I remove the most finished ones and roll them up.”

Cynthia Davis converts window screen kits, available in most hardware stores, into shelves for storage

Others have come up with creative storage solutions using materials readily available from Home Depot or Costco. “I used fiberglass window screens to acts as removable shelves for storing papers prints,” says Cynthia Davis. “Screen kits are available at hardware stores and can be made to fit any area smaller than 36 inches. I used screen because it is lightweight, compact, and allows for air circulation to help prevent mildew. The screen shelves are supported with clear plastic corner protectors. These are attached, horizontally, to the wooden sides of my existing storage area with small countersunk wood screws, which act as slides for the screens.”

Lydia Schrufer offers another shelving option, using wooden dowels affixed to the wall at an upward tilt.

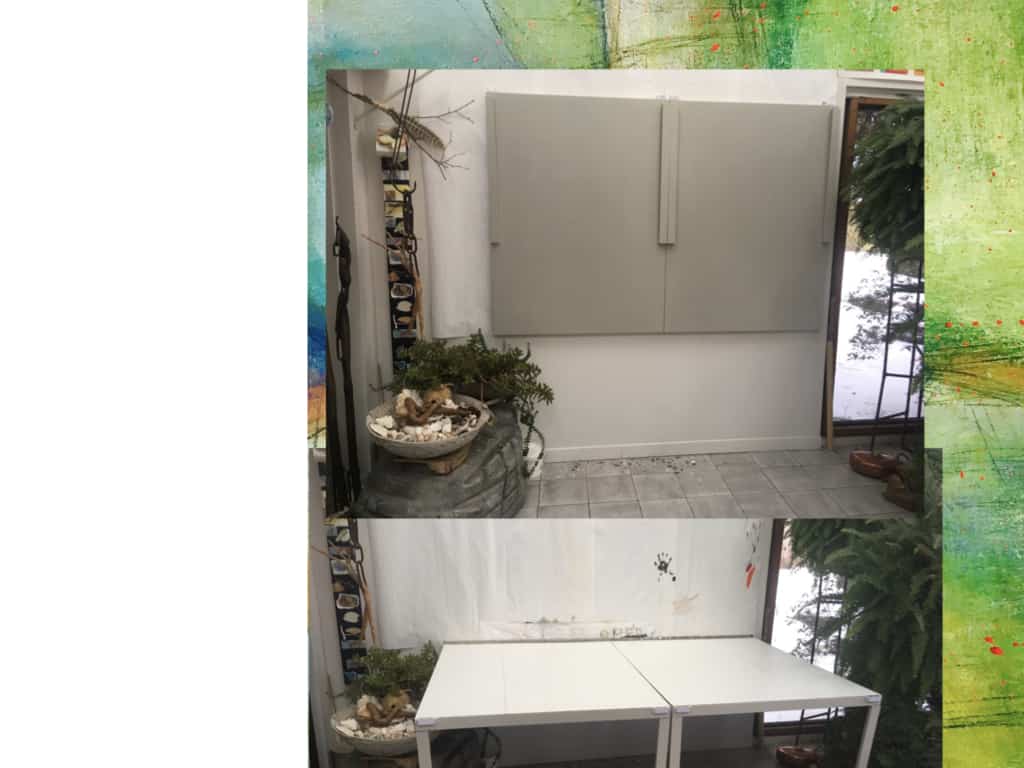

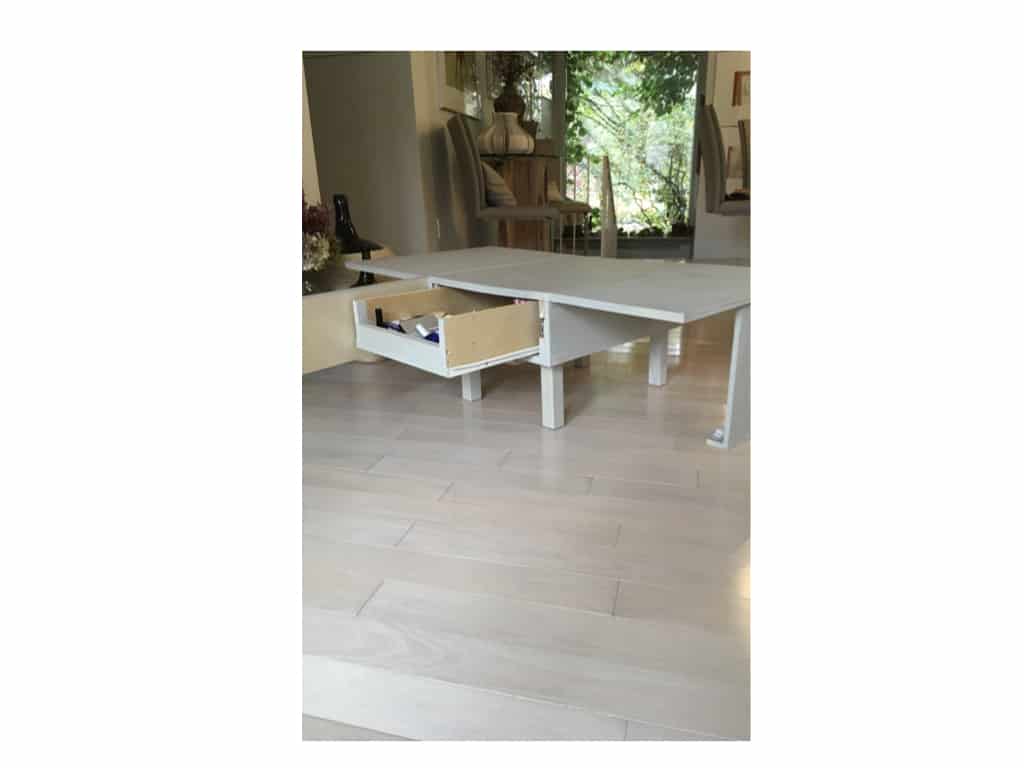

Schrufer, who plainly knows her way around power tools, has built a table that folds up into the wall…

….along with another versatile table that holds a deep drawer and folds down to a compact size that easily takes its place among her living-room furnishings.

Hold an Open Studio or a Fire Sale

There are a couple of ways to go about this: team up with other artists in your area, or turn it into a social occasion for select friends, supporters, and collectors. “I have one open studio each year, during the time one of my primary collectors come to town, and have a party, invite friends, and usually the works find homes,” says Susan Christie. Once every two years or so, as work piles up, Catherine Ruane says she holds an open studio and sells work in small batches. “This has been a productive option that helps me avoid low-ball selling,” she explains. “I do not want to hurt my market value or anger any of my collectors. There are some gallerists who don’t like the idea, and I understand their point of view, but my compromise is not to do open-studio selling to collectors in their area.”

This month, Christopher Rico is hosting what he describes as a fire sale in his new studio in Greenville, SC, a space that is about a sixth the size of his old studio in Clinton. “I previously worked in color and more of a geometrical abstract style against Turner-like undulating fields of earthen palette, he says. “I held on to representative examples of that work when I packed everything up, but as I settle into the new studio I simply don’t have the space.” He’s discounting the work to 2008 prices, and prospective buyers can preview most of the paintings in a self-published catalogue on blurb.com. “What doesn’t sell in a month will be documented again and then it will ‘go away,’” he says.

Give It Away!

When it reached the point where paintings seemed to occupy at least half her work space, Cydney Taylor, who was then living in Taos, NM, called Habitat for Humanity, a nonprofit organization that helps families improve the places they call home. “Take it away!” she said, and so they sent an “art person who came and checked out what I had to give,” she recalls.

Because she spent part of her career teaching and working in Montana, Sheila Miles has given many of her works to institutions in that state, including the Missoula Art Museum, the Yellowstone Art Museum in Billings, and the Holter Museum in Helena. If you do go that route, she advises, “Pick out your best. I’m a former curator, so I know the kind of quality museums aspire to. And be sure the work is labeled properly with the title on the reverse, along with the date and the medium.” You won’t be able to deduct the value of the work, but you can get a tax break for the cost of the materials. And your work may reach a larger audience through such donations. “I would advise people who are giving their works away to have a personal relationship with the institutions they’ve chosen for donations.” That might be a board member, a curator, or anyone on staff who’s shown an interest in your art.

Another option is to give works to a place where they might bring real joy and solace—a hospital, a clinic, a retirement home, or other institution. “When you think about it, people spend more time in hospitals than they do in galleries,” says Annell Livingston, who donated a wall of small gouaches to the new Presbyterian Hospital in Santa Fe, NM. “I have given works to retreats, too. I would consider any place to has to do with healing.” And when the installation is as handsome as the one below, everyone benefits: the staff and patients get a lift every time they look, and the artist gets a museum-worthy testimonial to her talents.

Ann Landi

Top: Cydney Taylor says good-bye to all that before moving to Olympia, WA.

The Art Connection, based in Boston, pairs donated art with nonprofits in the area. I’ve found it a very gratifying resource – the Art Connection staff make sure that the work is labeled and taken care of theartconnection.org/

Ann, thanks so much for this article. So many great ideas were shared!

Diane

LOOKS GREAT!

As finding homes for my paintings is my primary focus these days, I am hugely grateful for this article, Ann. I plan to follow up with some of the ideas.

A couple of questions:

•How does one find, “a person to help … place … paintings with worthy organizations (like hospitals and nursing homes)” ?

•ditto a curator to help separate wheat from chaff?

I also offer another option: Last year (2017), two months before moving from Philadelphia to Seattle, I had a solo show at a non-profit community gallery (iMPeRFeCT), offered everything through a silent auction, and donated the proceeds to the gallery. With the gallery approval, I am inspired to repeat this for a forthcoming exhibit in January 2019 in Seattle.

Hi, Deborah: I would call a local museum to see if a curator in contemporary is available. Or work with a trusted art dealer. But I’ll refer both your questions to Annell Livingston.

Also, see my post on editing: https://vasari21.com/advise-and-select/

Of course, to find a curator, you could call your local museum, or art organization or university. I had three persons, I worked with, when I culled my work a couple of years ago. The process was interesting, each came separately, I paid them by the hour, and did lunch. Often what one liked the other did not, but the final decision about destruction was always mine.

Often the artist loves a work for unknown reasons, maybe it is a transition piece, that is the step to something more important, someone else might not see.

I found the person I hired to help me place my work, from my attorney, when reworking my will. She is retired, but with lots of experience, and knows lots of people. Sometimes it takes that. And she had done this before.