Landing a show at a small museum or university gallery

Let us suppose you’ve been hard-working and fortunate enough to have a slew of gallery shows, group and solo, on your CV. You’ve built up good connections and can perhaps even claim a following of dedicated collectors. Maybe you’ve even earned some notice from critics. You’re at the stage where you can honestly be described as a mid-career artist. Perhaps you’re not ready for MoMA or the Venice Biennale, but what’s next?

Most artists at this point aspire to an exhibition at a university or college gallery, a small museum, or an urban arts center—in short, a respectable venue with a good curator and a professional staff to pull it all together. But how do you make the approach and how do you sell yourself and the show?

It’s not an easy process. Even the most modest of university galleries have a roster of exhibitions in the making for two to five years. “We generally have our own program in the works for a few years out, so we usually do not look at unsolicited proposals,” says Tricia Paik, the Florence Abbott Finch Director of the Mount Holyoke College Art Museum. “When you go to visit museum sites, they almost always say they are not accepting submissions,” adds Tracy Linder, an artist who lives and works in Billings, Montana. “The frustration for the curators is generally that so many artists are approaching them who are an ill fit for their programming.”

Nonetheless, many site members have cracked this particular glass ceiling, and there are a number of smart ways to land a show, perhaps not next month or next season but a year or two or three down the road.

Finding a Venue

“Obviously the best place to start is in your own back yard,” says David S. Rubin, an artist, writer, and independent curator who worked for many years at the San Antonio Museum of Art. “You’ve probably frequented the venue where you want to do a show. Or maybe you grew up in a certain place but don’t live there anymore, yet you still have friends and relatives who do.” Which would allow for an opening like “I spent my youth in the Pacific Northwest, and the geography has always had a profound impact on my work.”

If you’re just starting to do your research, Rubin recommends consulting the Art in America annual guide to museums, galleries, and artists. Or google your home state, suggests Linder. “Iowa art museums,” for example. Is there a program where your art might fit in? Then do your homework carefully. Look to see what kinds of exhibitions have been supported in the past. Do you know anyone on the curatorial staff? Is there a specialty of the institution—say, printmaking or video—that would make you a good fit? Linder, who has a couple of museum shows in the planning stages, says, “If there are artists who are far more successful than I am, but whose work shows a relationship with mine, I will look then up and find out where they’ve had exhibitions.” Two whom Linder has followed because their works have affinities are Deborah Butterfield and Theodore Waddell.

Blind queries often go nowhere, but if you are at the mid-career stage, you should have a network of contacts who can ease your entrée. “To help distinguish oneself from the various proposals and emails that museums receive, it’s more effective for the artist to have an advocate—a dealer, a curator, or a critic—write to the museum on their behalf,” says Paik. “A lot of venues require contacts,” adds Andra Samelson, who has had successful shows at the Fayerweather Gallery at the University of Virginia art gallery and the Loyola University Museum of Art in Chicago. “I was lucky enough to have someone recommend me.”

“If you’re local,” adds Paik, “ask a curator to make a studio visit.” Another way to get a foot in the door is to serve on the board of a nearby institution, because often museums are looking for artists to be part of their advisory committee. “I was on the board at the Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art for years and years,” says Martha Russo, who makes her home in that Colorado town. “I wasn’t looking for a show. I simply wanted to know how a museum works and how to interface with everyone.” But eventually the director approached her about doing an exhibition, and the upshot was a small but handsomely installed retrospective in 2016.

Making the Approach

Whether you are sending a proposal email or snail mail, blind or solicited or through an intermediary, make it as smart, professional, and tailor-made as possible. “Starting a conversation from scratch is difficult,” says Linder. “Most often I open up a dialogue by talking about a show that’s recent or ongoing, so curators will know I’ve checked out the museum. I compliment them about the good work they’re doing and outline how my work might fit in. I’ve been warned so many times that many people don’t like to download material, so I include a couple of images, and if I’m making an email approach, I’ll embed images into the text and provide links as well.”

“Try to find out what’s the best way to communicate—email or snail mail,” says Russo. (You might call and simply ask an assistant.) “I’ve got several snail mail packets out right now,” adds Linder, “but when I’ve been googling museums, some expressly say, Do not send snail mail. Others say the opposite. It’s never an easy find.”

Jim Condron, a site member who has enjoyed several shows at colleges and universities, including most recently exhibitions at Goucher College and Loyola University in Baltimore, says he works closely with his partner, Stacey Lambrow, on tailoring proposals to the venue’s aims. “Goucher has a strong history of liberal arts and a strong economics department, so we pitched a show that would be relevant.” His exhibition had works that featured farm equipment, with the titles of the individual pieces drawn from a Willa Cather novel, so that “the themes were broad and interesting to a wide range of academic disciplines,” he says. “We carefully considered the university’s interests rather than simply asking them to show the work.” (He also called on this writer to do a question-and-answer session at Loyola, and claims I was “a massive draw.”) “Stacey’s thinking was, ‘How does the college benefit from my work? What’s in it for them?’ Once you turn the question around, it becomes easier to make a pitch the curators will find appealing.”

Thinking Inside and Outside the Box

If you have your eye on a particular college or university gallery, there are many ways to get your work noticed by the faculty and administration, says Erin Elder, an artists’ coach and curator in Albuquerque, NM. Look into visiting-artist programs or teaching gigs. “Sometimes those are hidden, not made public,” she notes. But you can always ask the relevant department (visual arts, studio arts, art history). See how your interests as an artist might jibe with academic programs. “There’s a lot of money in science for artists,” she adds. “Look at research laboratories, research facilities, how you can work with scientists to interpret the work.

“Oftentimes opportunities lie in creatively connecting the dots,” she continues. “How can I approach this institution and propose something that only I can do? See what opportunities are out there for interdisciplinary studies—what’s happening in astronomy or geology or anthropology? What can I propose that would bring in students? Maybe you can rack up a collaboration or offer lectures.

“Get over the idea of immediate gratification,” Elder further advises. “Be patient and curious and serious enough to nurture a relationship. An important part of an artist’s career development is thinking in terms of a longer view.”

If this all seems like too much effort and bother, there are a few consultants who guarantee placement with small museums and college galleries. Katharine T. Carter & Associates, based in the Hudson Valley, is one such resource. A contract with Carter offers “exhibition placement services for mid-career artists participating in higher level contractual services,” says the website. What that means, in effect, is that, for a substantial fee, you go through an entire program to package “the whole professional.” That entails an upfront consultation (generally about $500), and then a reworking of your artist’s statement and biography, essays by a professional art writer, production of a brochure, and other assistance.

Kim Thoman, a site member who went through the whole process, has landed shows through Carter at St. Mary’s University of Minnesota, the University of Oregon Cultural Forum, and the Anderson Center for the Arts in Anderson, IN. She has a couple more exhibitions on the agenda at the Goddard Center for the Visual and Performing Arts in Ardmore, OK, and the Hardin Center for Cultural Arts in Gadsden, AL.

“I paid $25,000 for the whole package but made sales of $9,000 in one of those venues,” she says, noting that this is somewhat of a rarity. “I had the financial ability to do this, and it paid off.” At the point she signed on, Thoman was stepping away from a long teaching career and “trying to dive into making art in a serious way.” But, she adds, “never spend this much money unless these are funds you won’t miss.” (A list of KTC artists and the venues where she has placed work is here.)

And in the End….

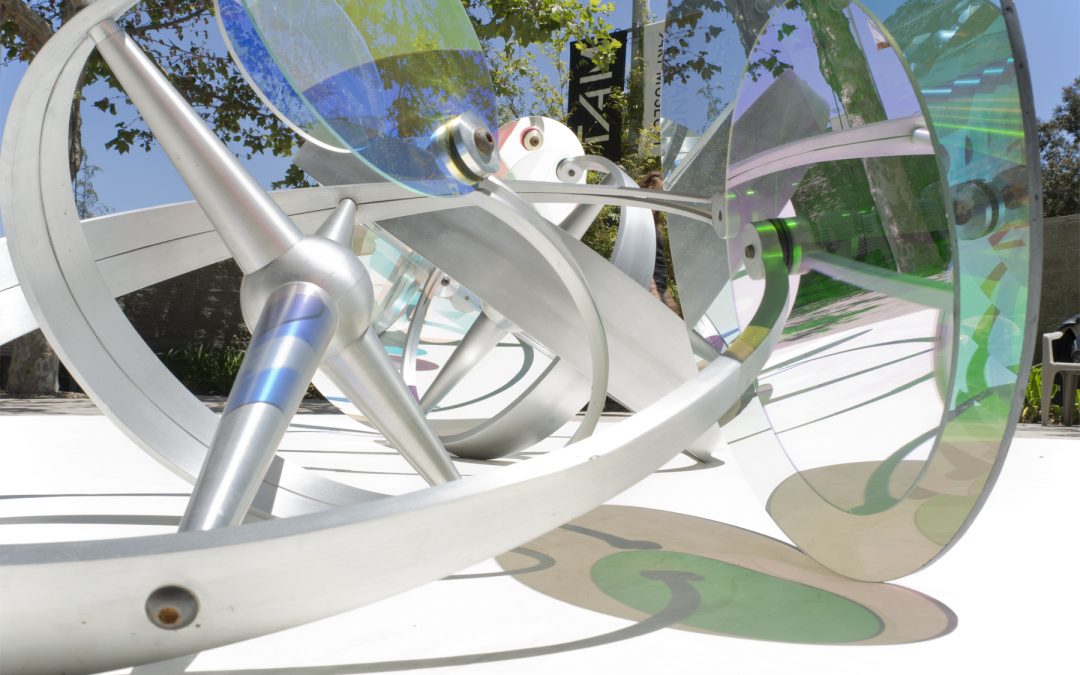

What I heard over and over from artists and curators was, Be persistent without being pushy. And be patient. “I made a good connection with the museum at Loyola University in Chicago and proposed putting something in the lobby,” says Samelson. “They really liked my work but didn’t give me a show for two years!” And “create an authentic network of artists and curators who are loyal and committed to you,” says Paik. You never know where valuable contacts will show up. Jim Condron met a couple of Harvard faculty during his residency at Heliker-Lohatan, and that led to a show at that august institution. When you run into a curator at an opening or a social function, get a card and fire off a “so nice to meet you” note. Jamie Hamilton, who recently scored a show at the Torrance Art Museum in Torrance, CA, met the curator at a round table organized by fellow Vasari21 member Virginia Katz. After the discussion, he ran into the curator at a local hang-out, where they exchanged contact info. “The next day I sent him an email saying it was a pleasure meeting him and thanking him for including me at their table. At the bottom of my note was a link to my website. He wrote me back, inviting me down to the museum to discuss a potential project.

The rewards of connecting, notes Samelson, are worth the effort and may go well beyond seeing your work exhibited. “The university venue is wonderful,” she says. “You get eager students who are open and young and curious, and there’s a lot of stimulating dialogue.”

Ann Landi

Nice and informative article! Thanks Ann!

This article was extremely helpful for a mid career artist…thinking about small museums or university galleries for exhibitions. Great advice.

Thank you for this Ann. Valuable and interesting information. Not there yet but making my way hopefully in that direction.

Thank you for this very helpful article, Ann.

Very informative. Thank you