How Critics and Curators Respond to Memorable Works of Art

In a recent issue of The New Yorker, actress Allison Janney reported of her first encounter with Wassily Kandinsky’s Black Lines (1913) in the Guggenheim Museum: “I felt an energy go through my chest.” I could identify. Even after decades of looking at art, I still occasionally feel a little thumpa thumpa (sometimes a big thumpa thumpa) when I come across a work that unaccountably stirs my senses.

Neither I nor anyone I know has ever suffered the peculiar aesthetic shocks known as Stendhal Syndrome, named after the great 19th-century French writer and described in a journal called The Florentine as “a psychosomatic illness that causes rapid heartbeat, dizziness, confusion, and even hallucinations when the individual is exposed to an overdose of beautiful art, paintings, and artistic masterpieces.”

Nonetheless I was curious to know if curator and critic friends had emotional and/or visceral reactions to works of art, ongoing or in the past. And so here’s an intriguing round-up.

Kim Levin: Perhaps I am immune to Stendhal Syndrome. I don’t cry at movies or at works of art in museums, although I know people who do, mostly men. I don’t swoon or faint at beautiful pictures or statues.

However, once in a while a work of art astonishes me, looking unlike anything I have ever seen or imagined. It stops me in my tracks. It takes my breath away. There should be a word for this, though it is not Stendhal Syndrome. Instead of beauty, what grabs me is art that goes to extremes, art that is unnerving or unbearable or incomprehensible. I am not immune to indelible art.

Christopher Knight: Only once have I wept in the presence of a work of art — I mean actual tears welling up—and that was in the early 1980s at the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, while looking at Giotto’s famous frescoes. The response was slow, not sudden. I think it came from realizing that everything I thought I knew about art could not account for how moving they are. The sense of loss was profound; liberating, too.

Karen Wilkin: On occasion, confronted by a particular work of art I’ve had an incredibly strong, unexpected, and unpredictable response. It can be from any period, a painting, a sculpture, a work on paper, a building, sometimes a video. It can be a work I’ve never encountered before or one I thought I knew well. I’ll spend what seems to be a reasonable length of time looking and then, when I try to turn away, the work grabs me by the shoulder and tells me that I’m not finished yet, that I haven’t fully grasped everything there is to be considered. It can happen several times in a row. Matisse has done this to me often. So has Titian. I’ve been stopped in my tracks by a12th century sculpture by Gislebertus from Saint-Lazaire in Autun and several of Anthony Caro’s last steel pieces. I spent three hours watching an entire Douglas Gordon video of a burning piano. (The guard kept giving me concerned looks.) I kept trying to leave, thinking I’d “gotten” the piece, but I couldn’t. It’s most exciting when this reaction is triggered by something completely new to me and/or puzzling. I suppose this is reverse Stendhal Syndrome; instead of needing to flee, because of sensory overload, I crave more and more, in spite of myself.

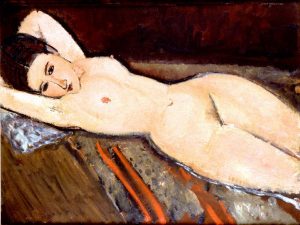

Judith Stein: As a high-school student in New York City, one day I was walking through MoMA when I found myself drawn to Modigliani’s Reclining Nude, c. 1919. I had seen her before, but this was different. My teenage self stood there and acknowledged one implication of being female, that I had the ability to own the sensuality that Modigliani had so magically captured.

Dan Cameron: I’m not sure it qualifies as real Stendhal Syndrome, but I’m a goose-bumps kind of guy. When I see something that truly rattles the bars of my perceptual cage, I get a tingly feeling at the base of the cranium, and maybe a quick cold flash to go with it. There’s also a deeply satisfying feeling of having been there before, even if it’s something I’m seeing for the first time, because the physiognomic reaction is so specific. In . fact, I almost never feel it when I see something again, no matter how long it’s been since the last time or how much I love it. It’s got to be something I’ve never seen before, in which case it has the potential to set off that kind of physical reaction.

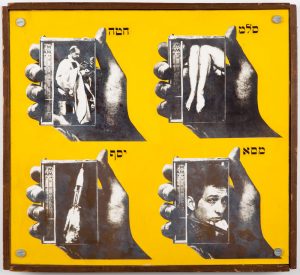

David Rubin: Two memorable experiences and one recent one come to mind. When I saw my first small Rothko painting upon entering graduate school at the Fogg Art Museum in 1972, I was dumbstruck. My response to the optical effects of light emanating from the painting evoked in me a feeling that was transcendent and ethereal. Almost a decade later, when I stood in front of a Wallace Berman “Verifax” collage for the first time, my mind went to another place and then came back. The presence of so many powerfully symbolic images in one grid, presented like X-rays, left me speechless…until a few minutes later when I thought to myself, “This is our universe, these are our options.” Last week, I had the pleasure of walking through the John McLaughlin retrospective at LACMA. There were multiple moments when I was stopped dead in my tracks. Through impeccable craftsmanship and compositional choices, which were particularly daring in terms of color juxtapositions, McClaughlin made me feel what Barnett Newman (who also mastered how to do this) called the sublime. In all these instances, I believe the artists appealed to something that is universal….call it heightened consciousness, being at one with the universe, or simply enlightenment, it takes a great artist to get us there.

Arden Reed: After years of repeated encounters with them, certain paintings continue to thrill me, to make various chakras hum, to provoke visceral if not synesthetic responses. Three examples:

A gray Agnes Martin whose name I forget. Because it’s the large, six-by-six-foot format, it fills your visual field; you relate with your body along with your eyes. Over a lightly penciled rectangular grid, delicate veils of the thinnest color seem to drift. They’re never quite where they were when last you looked. However material, the canvas provokes out of body sensations, indeed, out of this world, or “Ariel” sensations. I feel groundless yet serene.

Caliban comes to mind when I look at the Norton Simon Museum’s Stream of the Puits-Noir at Ornans (1867-68), a landscape by Gustave Courbet. Is it late fall or early spring? Dawn or dusk? In any case, my eye wants to follow the stream back into the recess between two massive granite cliffs. The overarching branches both invite and resist penetration. I hear the stream rustling as it spreads from back left and eventually spills out over the front edge of the canvas. And so the painting situates me in the stream, and my feet feel damp and chilled.

Between sky and earth, I locate an early Matisse in the Phillips Collection: Studio, Quai Saint Michel (1916). Curtains part, inviting us into a classic Parisian garret, circa 1910, where I smell fresh paint on a canvas next to the empty chair. The artist has just sketched the contours of a nude, reclining on a sofa covered with a red cloth. I hear him asking her to remain just so—he’s got the pose he wants. If I looked out the tall windows behind the chair, I’d see some steps descending to the Seine, a tower of the Conciergerie, a spire of the Sainte Chapelle, and from upriver I would hear the bells of Notre Dame chiming.

Ann Landi

Top: Even a replica of Michelangelo’s David can cause sensitive souls to weep

Love reading these accounts that remind us all why art is so important.

Picasso’s “Guernica” took my breath away when I saw it in New York many, many years ago. You could almost hear the painting it was so powerful!

I once had a full on Stendahl Syndrome experience — I was sitting looking at a painting and the branches of a painted tree lifted from the canvas and entered the room. I grabbed the seat I was in and held on until the feeling passed. I didn’t know what the phenomena was called before. Thank you. Now I know I am not crazy.

I can think of several experiences I’ve had with paintings that caused a very powerful emotional and physical response. My love affair with the work of Morandi has been steady over the past 40 years, so of course I was eager to see the 2008 Met Museum exhibit. I was overtaken by tears when looking at several groupings of his paintings and was unable to pull myself away. My legs trembled and the people around me seemed to dissolve. I have also felt physically shaken and been brought to tears in the presence of certain paintings of Rothko and Reinhardt. I’m not comfortable using the word transcendent, but these experiences were exactly that.