The whole notion of recycling seems a very up-to-the-minute politically correct attitude for art in this day and age. And yet the tradition of integrating all manner of stuff from the real world into sculpture and onto two-dimensional surfaces begins more than a century ago with Picasso’s breakthrough collage Still Life With Chair Caning (1911-12), which incorporates a swatch of oilcloth imprinted with a material commonly found on chair seats and backs. Two years later he made a tabletop sculpture in bronze called Glass of Absinthe, adding a real absinthe spoon holding a sugar cube atop the glass. (Absinthe, an anise-flavored liqueur, was originally prepared by pouring the bright green liquid through a sugar cube resting on a slotted spoon.) Picasso spoke of his desire to explore different modes of representation: “I was interested in the relation between the real spoon and the modeled glass. In the way they clashed with each other.”

Pablo Picasso, Glass of Absinthe (1914), painted bronze and perforated tin absinthe spoon, 8 7/8 x 5 x 2 1/2 inches

That seemingly simple gesture opened the floodgates to decades of artistic plundering in the real world. If you were like Marcel Duchamp, who appropriated a snow shovel and a bottle rack wholesale as art objects, you didn’t even bother with making any gestures, like applying paint or supplying embellishments or turning the mundane source material into expensive metal. But in the years since these first forays into the mash-up between the real and the invented, artists have raided sidewalks, dumps, dime and grocery stores, yard sales, newsstands and mailboxes, and collected the detritus of the natural world to spin ordinary stuff into visual delights and puzzlements.

Two of the more extreme examples of this brand of artistic license are Jessica Stockholder, whose works “challenge boundaries, blurring the distinction among painting, sculpture and environment, and even breaching gallery walls by extending beyond windows and doors,” as Carol Kino wrote a few years back. And Rachel Harrison, currently the subject of a mid-career retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Her work—which includes things like children’s toys, clothing store mannequins, life-size skulls, defunct appliances, bedding and “sealed garbage bags filled with you don’t want to know what,” as New York Times critic Holland Cotter put it—has inspired wholesale dismissal from some critics and deeply admiring reviews from others.

Most of the Vasari21 members who answered the call for “recycled art” don’t go to the kind of extremes that have characterized works by Stockholder and Harrison, finding instead a middle ground that will probably resonate with larger audiences. In that fertile territory, the artists presented here, in two parts, find ways to inject their creations with humor, bite, delicacy, whimsy, and sheer delight. The wonder is that so much cast-off and underappreciated stuff is undergoing transformation and finding its way into collections and on to gallery walls.

Jim Condron: I can trace the use of recycled materials in my work to the time I learned that my mother had ALS, a neuromuscular disease, though in general I really try not to think too hard about the overt meaning of things. My mother was my first country uses my mom’s clothing, along with straw and yarrow. Pieces like these that I made for Wings Over Wall Street, the MDA benefit in New York last spring, are obviously directly related to my her struggle with ALS and her death. .

On a lighter note, As she tried to approach. . . uses Grace Hartigan’s canvas and was an homage to my time working with Grace as her graduate assistant at the Maryland Institute College of Art while I was a student.

As she tried to approach him, he moved sideways a step at a time (2017), oil, plastic, fur, Grace Hartigan’s canvas, 27 by 13 by 3 inches

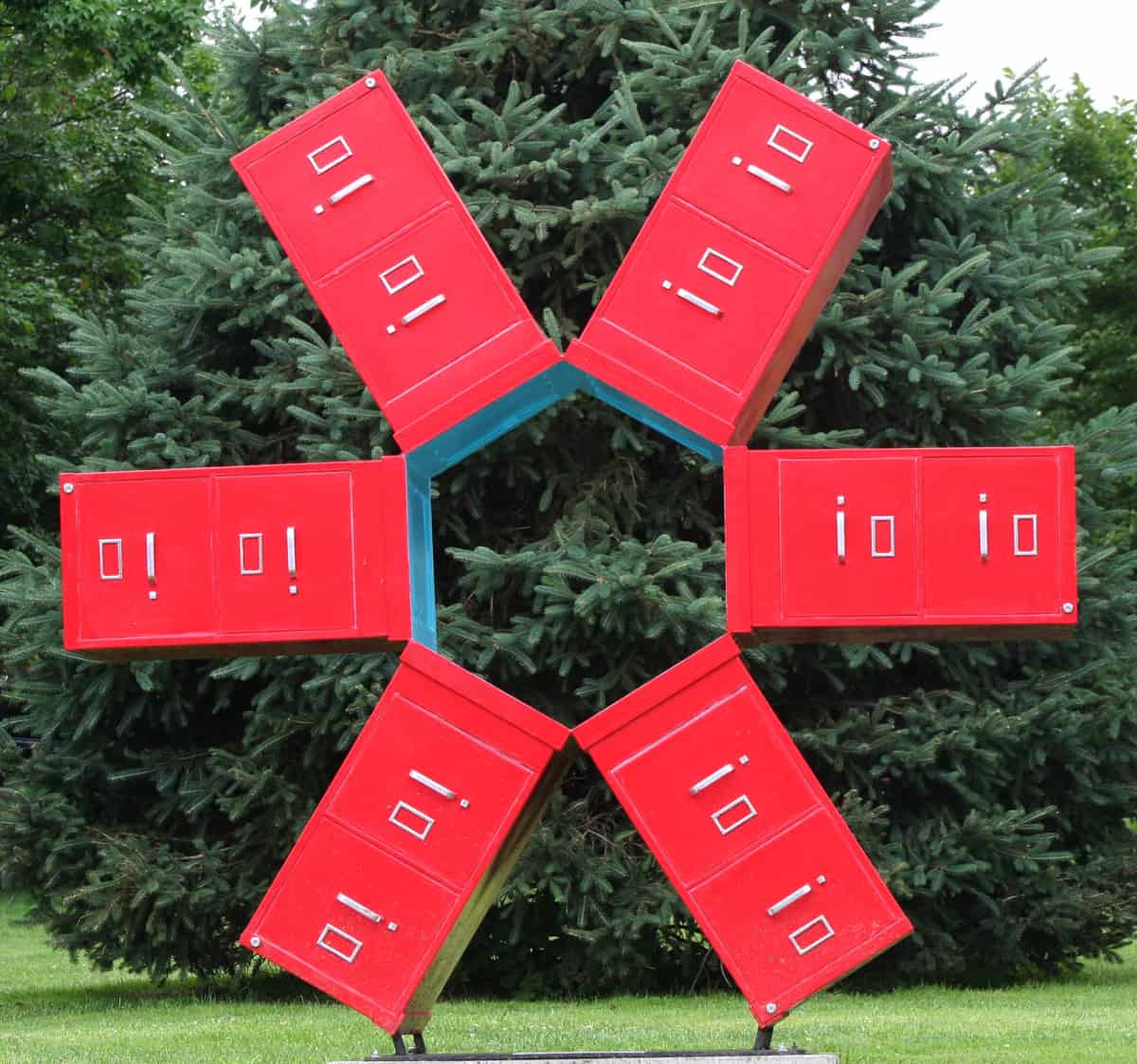

Barbara Lubliner: I have been using castoffs in my sculpture for years. Thinking that I’d make armatures and stands for my figurative pieces, I learned to weld in the early 2000s. I wound up welding found metal into “rattles,” interactive toy-like sculptures that were like cat toys for people. I am attracted to how a found object can keep its original identity yet assume another role and have an abstract formal logic in combination with other forms. The use of recognizable found objects stimulates associative connections, adding resonance to the work. My largest metal piece, File Cycle, consists of six file cabinets welded together and was created for Stamford, CT, which is known as “the city that works.” The sculpture was part of Stamford’s 2007 Art in Public Places exhibit.

From found metal I moved to found plastic, primarily bottles. From single-use bottles I devised a system of joints and components with which I build structures and dogs. I did a number of public projects, most recently Plastic Bottle Succulent Garden for the City Reliquary Museum. I fashioned beverage bottle discards into an abstract rendering of a succulent garden.

For another upcycle project, I was fortunate to be one of the artists invited by Edison Price Lighting to use factory discards to make work. I manipulated copper circuits, laser cut steel, wire, and metal shavings into weavings. The pieces I created play with each material’s reflective qualities.

Peggy Klineman: I began my journey working with upcycled/recycled materials as I was getting ready to leave my Manhattan apartment of 30-plus years for more spacious digs in the country. I had amassed tax returns, financial statements, receipts and cancelled checks from as far back as 1980. I couldn’t just throw them out, so I began shredding them. In the process, I realized what a great raw material for my artwork they would make. That was approximately eight years ago. Since then, I’ve expanded to include selected materials from my own garbage. So many things we throw out have wonderful qualities which are overlooked. I am especially drawn to materials with transparency and shine. I also like plastic netting. The possibilities are endless.

Through my art I give voice to the mundane and elevate it to something precious. I am spotlighting how wasteful we are. Shedding light on how our garbage impacts the environment, especially that which we discard and can’t recycle. It can be repurposed. My art is an example of that, and I hope gives others ideas too!

Carole Kunstadt: As a young artist, many years of working in collage fueled my appreciation for ephemera—ledgers, receipts and antique journals, which I incorporated into my work. The echoes of history and the stories hinted at but yet not deciphered were compelling to me as source material.

Currently, my works reference antique artifacts combined with the material of antique books, deconstructing paper and text, and using it in metaphorical ways. A book is not only the way in which text is presented but it is a container. An irreplaceable aspect of the book is that books absorb histories. Similarly objects retain energies and are evocative of the past. These aspects inspire the work. Through the exploration and manipulation of the materials, the process reveals how language, memory, and history become visual through re-interpretation.

Ovum I: Homage to Margaret Fuller (2016), ostrich egg, steel cut tacks, repurposed vintage fur muff, and paper: fragments from Woman of the Nineteenth Century, and Kindred Papers Relating to the Sphere, Condition and Duties, of Woman, by Margaret Fuller Ossoli, 1855, 6.5 by 10 by 10 inches

Pressing On: Homage to Hannah More, No. 76 (2018), antique sad iron, linen thread and paper, pages from An Estimate of the Religion on the Fashionable World, by One of the Laity,1791, by Hannah More 6 by 3.5 by 5.5 inches

Etty Yaniv: By using recycled material, I am making an environmental statement. I am very concerned about what’s happening to our planet, and sense a need to express it as a layer in our existence today. I have been including so far mostly paper, plastic, and more recently, some fabric. The materials range from found objects such as shipping materials and cables to fragments from my studio practice, such as drawings and photographs.

Sirens (front), 2014-19, mixed media immersive installation, plastic, film, paper, about 8 by 12 feet, and Labyrinth (back), 2015, paper, plastic, film, 13 by 6 feet by 8 inches

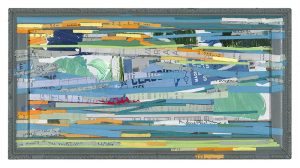

Marcel Speet: Like most artists, I offer a different view on reality. I believe that art can be inspiring for viewers and even affect behavior and thinking patterns. Recycling is almost instinctual for me. I love and re-use materials that are rich in history or sensual qualities, from 100-year-old Canadian pine to the latest papers and textiles.

I like coincidental color schemes, fashion, and architecture. I’ve done some social art projects with urban neighborhoods. Lately I’m in love with old and new textiles—the surface, the feel, the surprising colors and structures.

.

HZxt9, from the “Huayi HZxt” series (2019), incorporating 100-year-old Canadian pine, 25 by 18 by 5 centimeters

GC34 Gant de Couleur (2019), double-sided assemblage, fabrics and acrylic paint. 35 by 20 by 4 centimeters

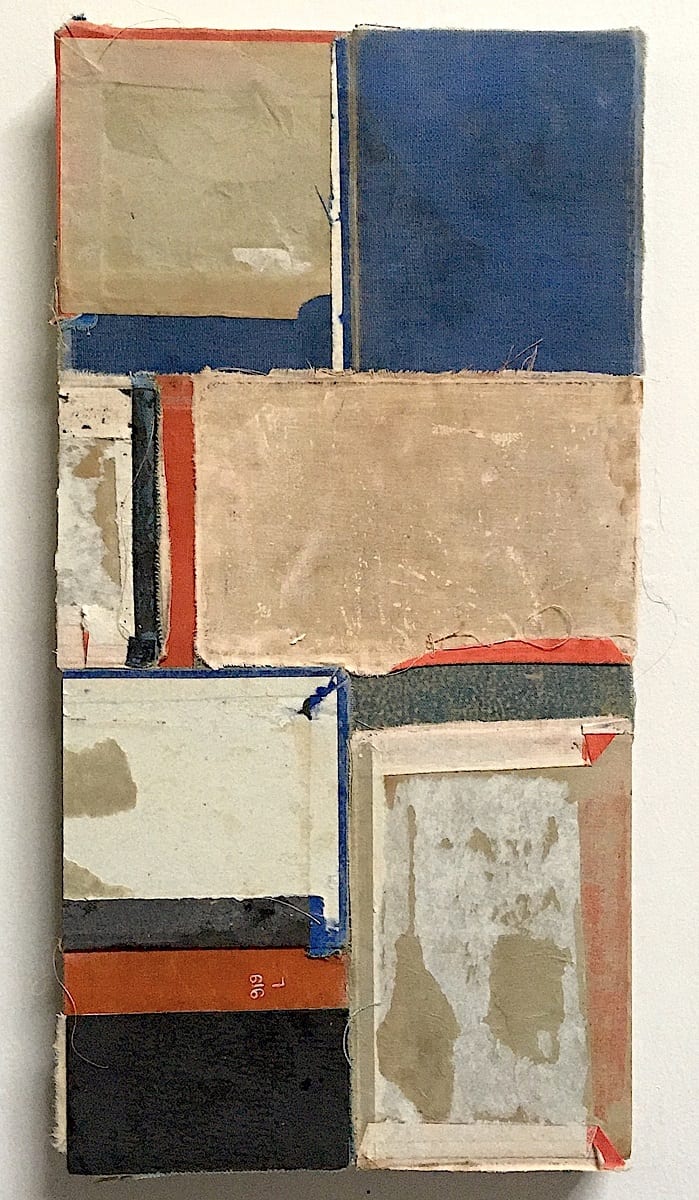

Kerith Lisi: I like using materials that are deemed to have no monetary value. While I do work with discarded books, I use only those that have been picked over by hundreds of people. Fortunately, I live quite close to a library that receives massive book donations on a monthly basis. These books are priced to sell to the public and the ones that do not, then get moved to a “bargain room” for sale at just $5 per bag the following month, one weekend only. At the end of that weekend, teachers and non-profits are welcome to come and take what they want for free.

Many books are damaged from light, from moisture, from a puppy chewing on the corner. I load up on what calls to me and take them home to deconstruct and salvage what looks interesting, often passing on pages to other artists to reuse. Just as walking into a room full of books is full of surprises, so is opening the books when I get home, discovering something placed inside (a love letter, a recipe, even a telegram sometimes).

I keep thinking I’ll tire of books soon and move on to something else, but I don’t feel like I’m done yet. There is just something about taking something that is tossed away and worn out, dusting it off, and letting it tell a story. It is cathartic to lift up and repurpose that which might otherwise be lost.

Jan Sessler: I’ve long been drawn to collecting found, discarded, or recyclable items that I come across, whether it be on a walk, at a yard sale, in the discarded section of the library, or on the ground as I step out of my car. I am intrigued by the weathered beauty in nature’s transformation of something that’s been tossed aside, moving away from what it was originally intended to be. This dialogue between contemporary culture, nature, and time inspires me. I collect these found artifacts and repurpose them to be seen in a new light. Sometimes it takes several years before they are incorporated into a collage, assemblage or sculpture.

Ten years ago ago I also started repurposing recyclables into my sculpture, with the negative space forming the body of the work. I pour cement and recycled paper into forms I create with plastic, paper, cardboard, cartons, or other recyclable containers. In this way too I am seeking to honor the material in a new way.

Sueños (2010), discarded paper from cement bags, found foam, pencil shavings, charcoal and paint, 20 by 8 inches

Wise Elder No. 3 (2020) elements include a found handle, center of a tape roll, discarded wood, cactus wool, cement base poured into plastic plate, 15 by 6 inches

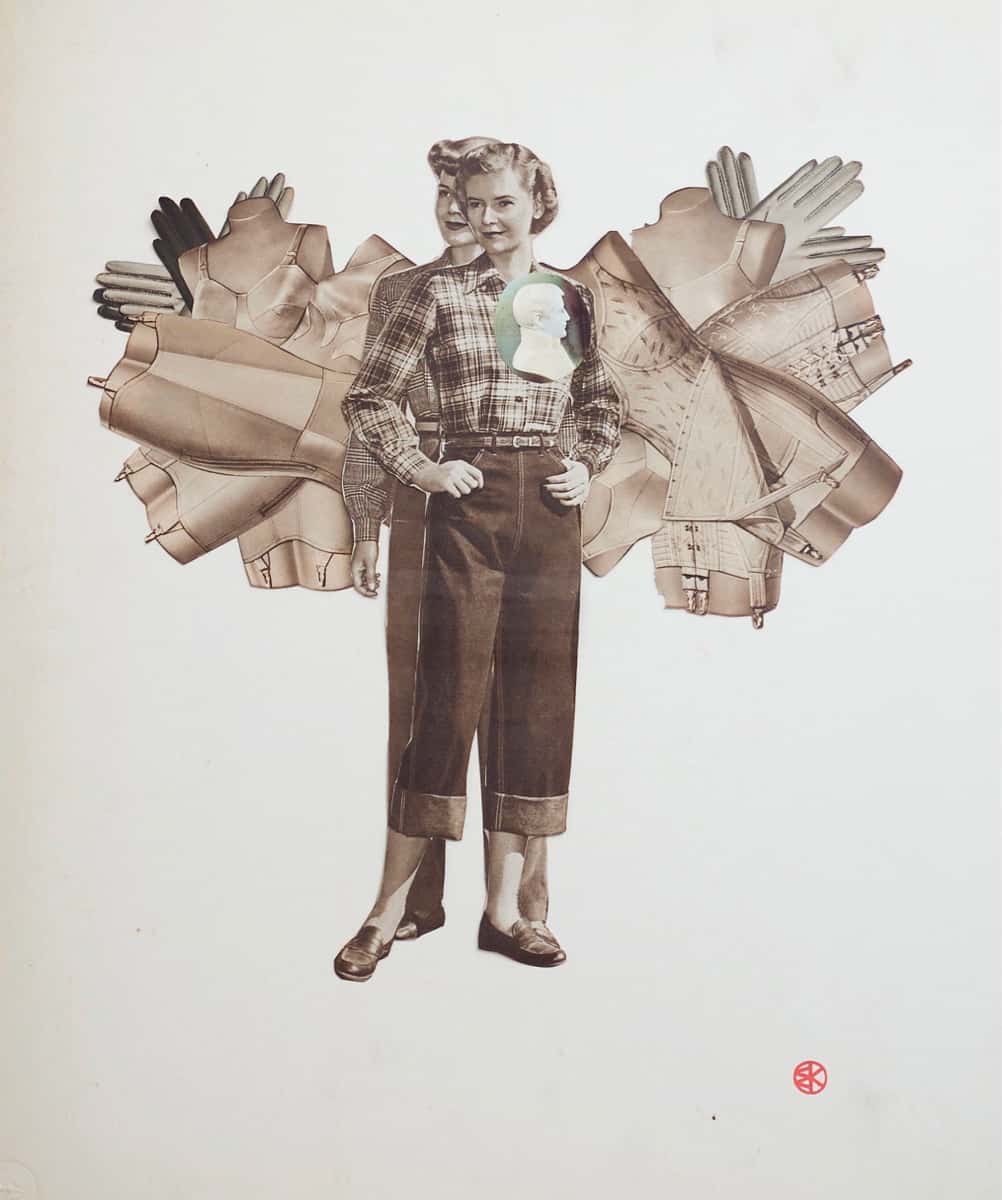

Blythe King: My recycled images have a sense of time. By transforming photographs of models from old mail-order catalogs (circa 1940-80), my work shows the age of the images, at the same time it offers new ways of seeing them. The styles are dated, the images are faded and well-worn, but they are also transparent and radiant, revealing a look beyond the surface, as in Fox Nature. Through collage, my portraits remind us of the lasting effects of advertising, at the same time that they liberate each figure to become a source of wonder and intrigue.

I’m interested in recycling images for a number of reasons. First of all, I collect old paper. To me, there’s a warmth and beauty in the way that paper shows its age, and I love the feel of materials like old envelopes, magazine pages, and newsprint. Second, as an artist, I want to draw the viewer into my work, and I think the familiarity of these images of fashion models makes the art accessible. We recognize the women in my work as advertising from another era, but how have they changed through the art process? The images also make me think a lot about my own experiences growing up in the 1980s, poring over mail-order catalogs. I wonder about how we internalize these images and what happens to them over time.

Top: Peggy Klineman, Garbage Collage (2019), mixed media on cradled panel, 12 by 16 inches (photo: Stephen Petegorsky)

Thoroughly enjoyed this, thank you – so appreciate the thought and care we put into dealing with “stuff” left behind. some amazing inspiring work here.

I appreciate the thoughtful writing and artwork here, but am disappointed that there are no photo credits. Since it is often a fellow-artist who has made the images that are included here, it seems only fair and appropriate to acknowledge and credit their contributions.

Please let me know where photo credits are needed. I depend on the artists to supply this information, but I’m sure they are not always aware that this info can be included.