Thirteen Who Head for the Open Air…in Spite of the Challenges

Artists in significant numbers first took to the great outdoors to work in natural surroundings and more accurately transcribe the effects of light nearly 200 years ago, following the example of landscape painter John Constable, who never inspired a movement in his native England but led the way for a group of French painters to tramp through the woods and fields with portable easels and paint boxes. Known as the Barbizon School, after the forest they frequented, many treated their subjects—peasants and rocky fields and sun-dappled trees—with a new brushy looseness, which later inspired the Impressionists when they turned their sights to outdoor pleasures, both urban and rural, later in the 19th century.

Abandoning the studio (or working only partly indoors) soon gained a foothold in the United States among the Hudson River painters and those who ventured west to capture the newly discovered natural wonders beyond the Mississippi. (In part, plein-air painting owes a lot to the introduction of paint in tubes around 1840; before then, artists mixed ground pigments with a binder, which were messy and difficult to transport.)

Fast-forwarding to the present, and in spite of all the developments in Modernist abstraction, working outdoors, directly from nature, still holds a broad appeal among many painters and sketchers. It’s a way of better understanding the effects of atmosphere and light that even the most advanced photography can’t capture in all its nuances. And it’s an excellent opportunity to get some fresh air and exercise.

As Jivan Lee puts it, plein-air painting can also be a way of understanding your place in the universe: “it’s a humbling endeavor, which I believe leavens the artistic pursuit somewhat and helps deflate overly grandiose notions of one’s place in infinite time and space.”

The 13 artists included here vary in their mediums and approaches: Some make sketches on the spot to use as a springboard for larger efforts; others work exclusively out in the open. But virtually all still employ traditional mediums: charcoal, pencil, pastel, oil and watercolor. The only comparatively new-fangled tools are acrylics and marker pens. Nonetheless, the astonishing variety to be wrought from the basics will be abundantly evident below.

Jane Shoenfeld: When I am painting en plein air, my medium of choice is pastel. There’s tension and excitement as I feel for the essence of what I am seeing and experiencing. The energy beneath the surface is more important to me than what I perceive with my eyes. Interpreting that energy is what motivates me. I avoid the seduction of beautiful details. Painting outside is exciting and requires absolute attention because the visual elements are constantly changing. Pastel’s vibrant and forgiving immediacy is perfect for plein-air painting.

Martin Weinstein: I have always loved the act of painting outdoors. The adrenaline rush of painting quickly changing weather is addictive. The pressure to capture this aspect of reality is so strong that it cancels all the voices of doubt or laziness that might otherwise prevent my working.

These paintings are made on layers of transparent plexiglass, which capture fragments of the landscape painted over periods of days, months or years. These two, different processes; the quick plein-air response to the immediate present and the slow accretion of these responses over time is the heart of my work. Never has the fragility of our natural environment seemed more heartbreakingly beautiful.

I was raised to be an abstract painter, so I missed out on a lot of the methods that traditional plein-air painters have learned to deal with the challenges of nature. It was only a couple of years ago that I was taught the trick of suspending a bucket of water from the easel to keep the wind from knocking it over. Still, I frequently find everything flying around and myself covered in paint.

Clouds and River, October, 2 Years (2017-18), acrylic on multiple acrylic sheets, 20.75 by 27 by 3 inches

June Yokell: While I have done plein-air work in the past, most of my paintings have been studio work done from photos I’ve taken while hiking or walking or just moseying about. I don’t know why I stopped working directly from nature on site, probably the little annoyances, like the wind coming up and knocking things over, or the fact that I’d have to gather up my materials and then haul them somewhere, start painting and then have the wind knock it all again.

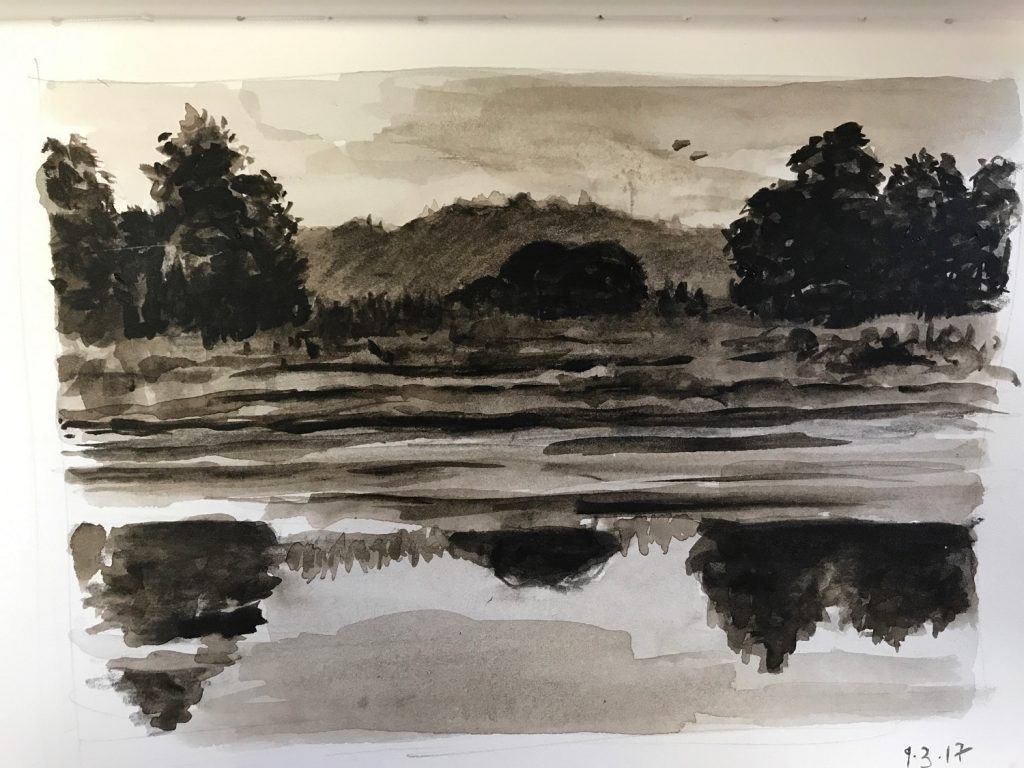

The painting One Fine Day was made from looking directly out of my studio window, so I had the luxury of my studio minus the hassles, though still constrained by the changes of light. The ink drawing was done on site, in the field, but because the materials were so simple I had more control over the outcome. I love nature, and I love painting outdoors and one of the reasons is that I know that the light will change and that I have limited time, I am forced to be totally in the moment.”

Greta Young: I work plein air for the sheer enjoyment of being outside and fiddling in the gorgeous New Mexican air. Usually I go with a friend and make paintings while chatting and eating chocolate. What could be better? Chatting, painting and eating chocolate!

Brian Shields: I was a plein-air painter for close to three decades, and though I still make sketches and an occasional painting on location, I now tend to gather Images—colored by energy and emotion—on long walks, then render what comes of that experience in my studio. Painting on location is about exploring ways to represent the natural elements; the challenge of plein-air painting for me is always one of entwining the visual, sensory, and emotional environments — and all of it transpiring on a relatively small surface. However, when I take the image indoors I am able to condense the memory and work at scale — and I have plenty of time to enter into a more intellectual exploration.

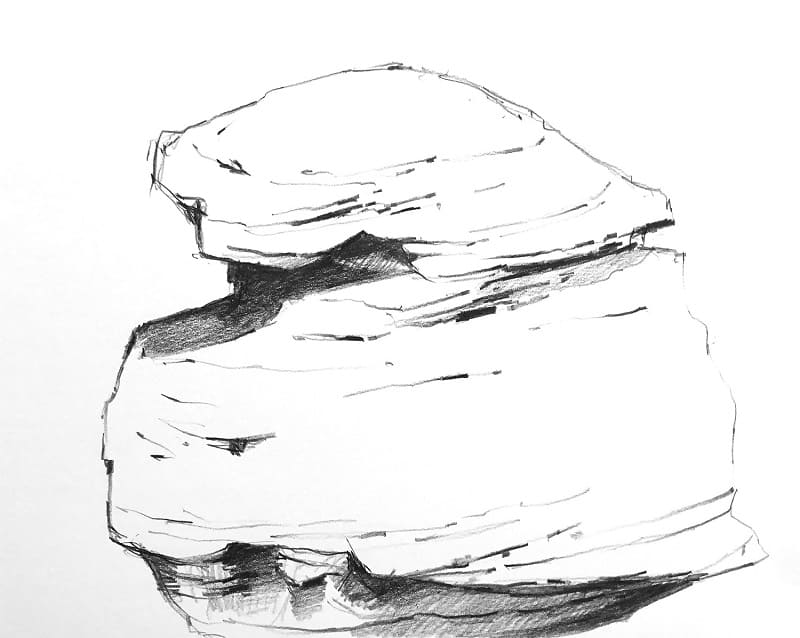

Frances B. Ashforth: During a residency at Ucross in Wyoming, I hiked every morning with a few friends up to these wonderful ridge lines where we could see for miles. The view of the Big Horn Mountains was spectacular. One morning we stumbled across a field full of boulders, which truly looked as though they had just dropped there. The ridge above was craggy basalt, and these were huge singular limestone boulders with no apparent relation to the geology of the ridgeline. When the director visited my studio, she said, “Oh, I see you found the Hobgoblins.” I hiked back to visit and draw these boulders/Hobgoblins quite a few times. I finished five larger drawings in my studio, using my field drawings, as well as referencing back to photos I took for light and detail.

I am mainly interested in drawing outside in the early morning or end of day, times when light contrast and shadows have the most interest to me. Since my drawings are black and white I really enjoy drawing in stark environments, and winter is my favorite time to draw stone. To me, stone truly shines during those months when foliage is no longer a distraction and the black, grays, and whites of winter allow me to focus more directly.

I carry my drawing gear in a backpack, so generally I am working on a 11- by 14-inch pad. Sometimes I snowshoe in to where a good granite outcropping is located. Yes, I have lost pencils because of a gust of wind and once brought all my gear on a river trip, only to have it rain for the entire week. I have many journals and sketchbooks with squashed bugs on the pages, but it is all worth it to me.

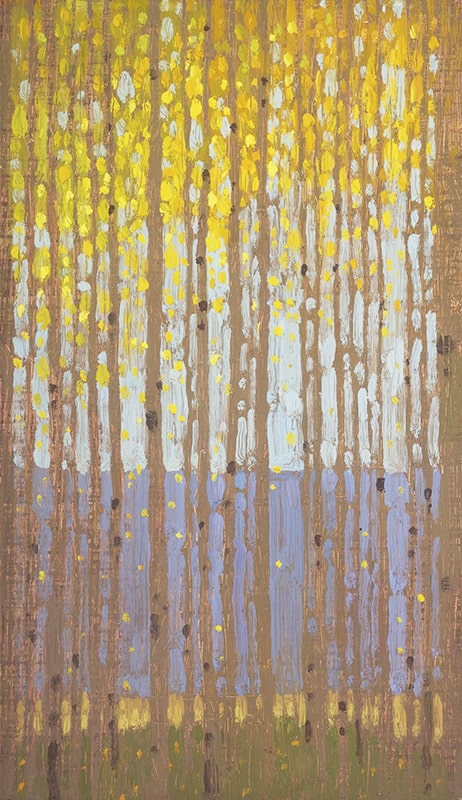

David Grossmann: My paintings of the world around me reflect my longing to find a sense of peace and shelter. The forest, the transitions of colors in the sky, the quiet watchfulness of deer and of birds, the flow of time and seasons…these are where I often look for refuge. My hope is that these paintings will convey a sense of haven, and that they will be reminders of the peace and the beauty that always surround us when we pause to watch and listen.

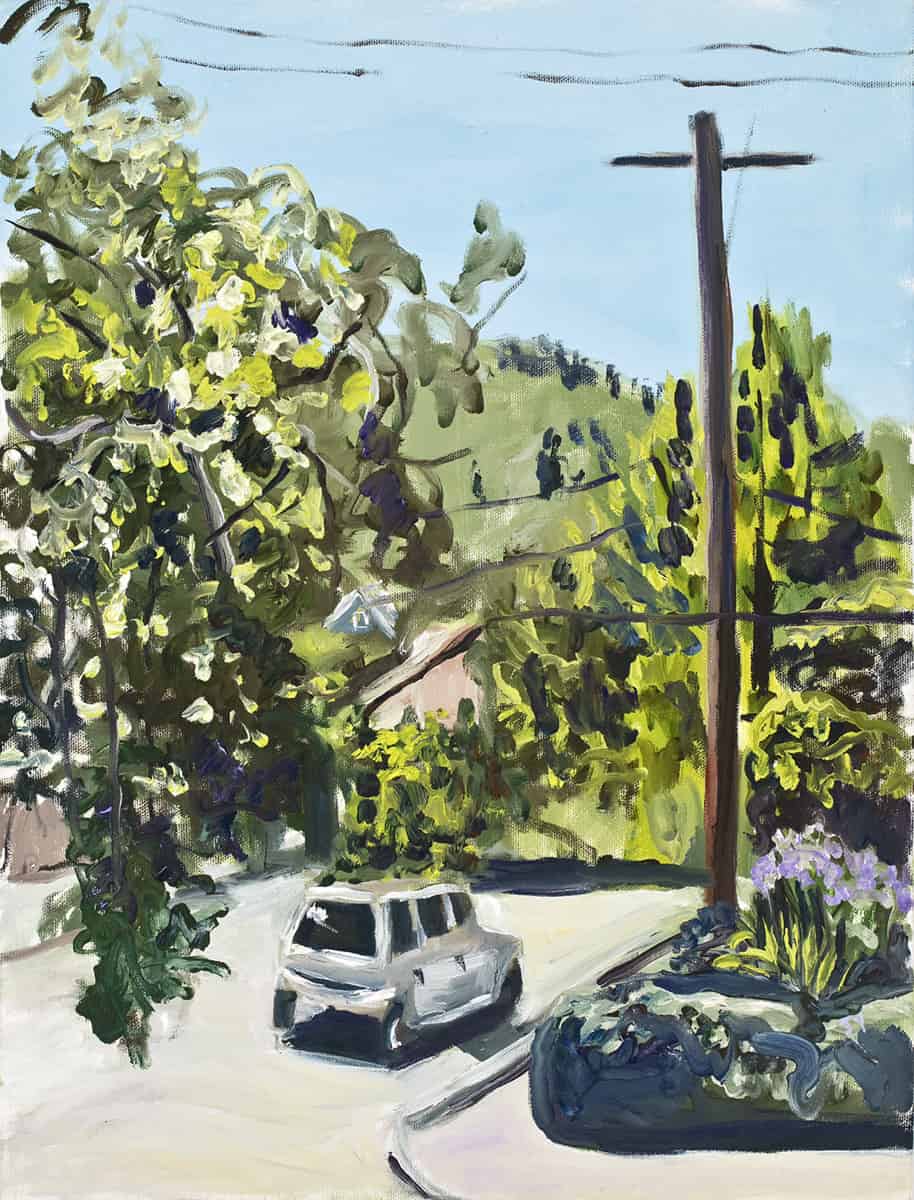

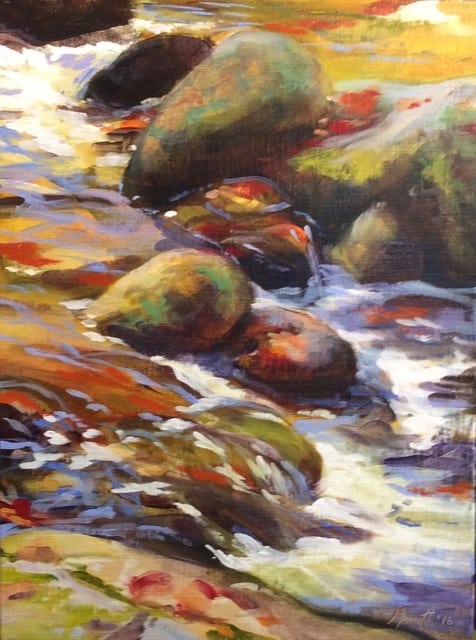

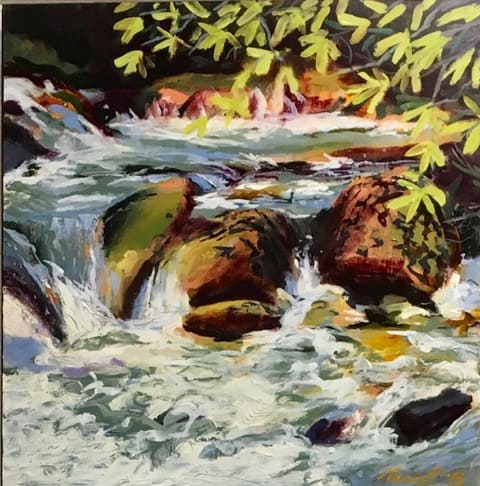

Phillip Garrett: I sometimes do smaller studies plein air and then use those studies and photos to scale up and finish larger works. The two below are of a headwater stream in the Blue Ridge Escarpment area in South Carolina, a place called Jones Gap. Over many years I hiked the area, fly fished for trout, and enjoyed the beauty and serenity I found there.

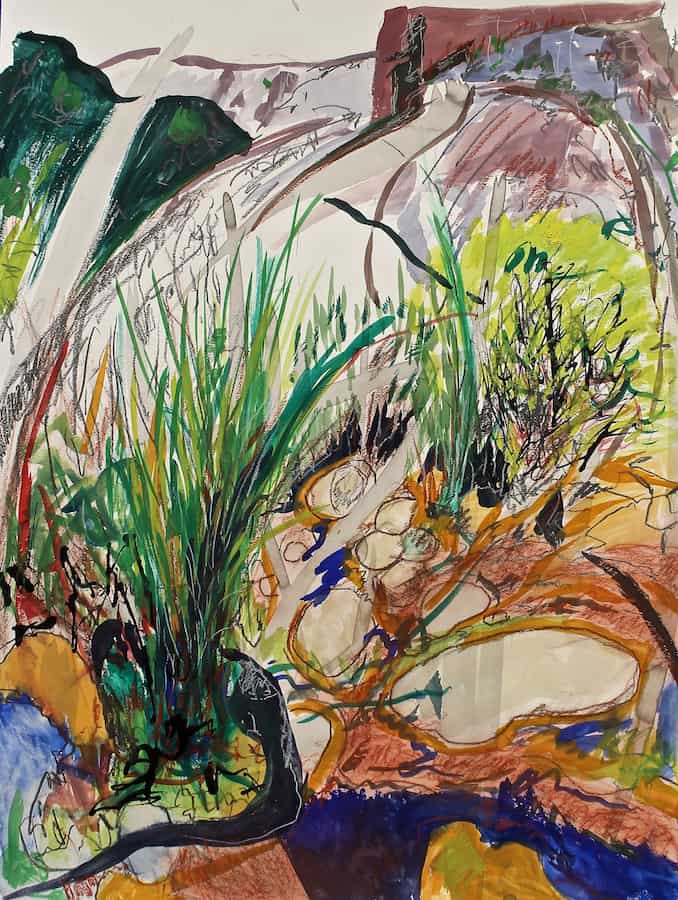

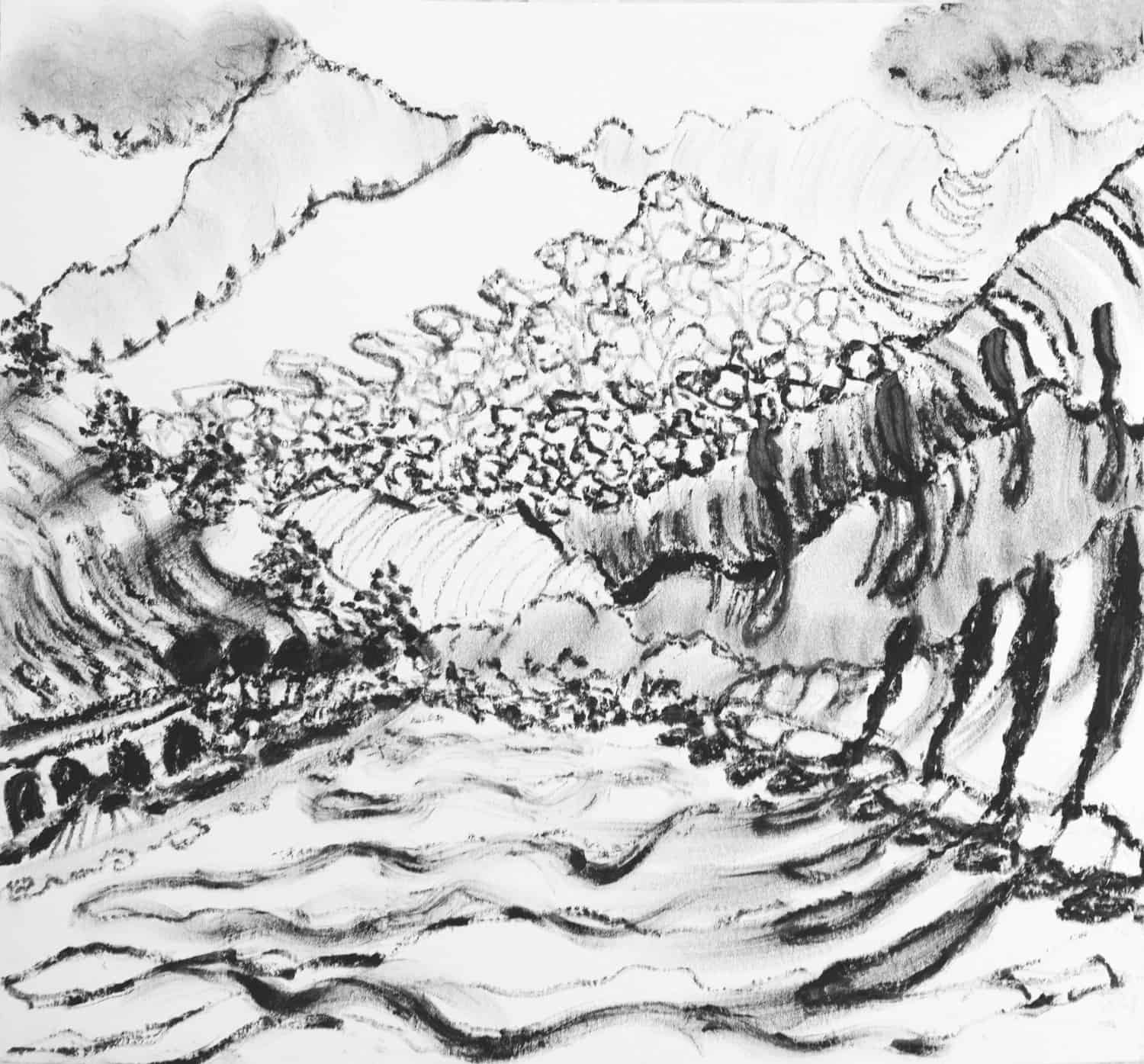

Lily Prince: I approach a place of particular interest with plein-air drawing, beginning in black-and-white oil pastel, moving to color and then to paint. These are the basis for my larger studio works. Returning repeatedly to a specific view, I combine illusionistic space with the interpretive mark-making inherent in an abstract ordering of the chaos of nature. In these times of environmental and societal devastation, I consider it a political act to immerse myself in the landscape to record the natural beauty lurking there—perhaps to incite the arousal of sentiment, a stirring of connectedness.

I consider myself an explorer, studying the atmosphere of diverse spaces. My initially observational works portray the pulsating rhythms and fecundity of New York’s Hudson River Valley, Tuscany’s Crete Senesi, and the Lake Como area of northern Italy. Plein-air drawing represents my visceral connection to nature, to the energy emanating from a specific evocative terrain, and my constant longing to return to it anew, like recurring waves of arrival.

Jivan Lee: The direct experience of color and light is a big reason for working plein air, even when there are elements that are fundamentally uncontrollable and frequently unexpected.

And yet, though working outdoors is beautiful, exhilarating, intimate, and unlike any other creative process I’ve experienced, it sometimes hardly seems worth the effort. This summer while I was on location in Taos, NM, a gust of wind from a nearby thunderstorm picked up my eight-foot shade canopy—even though it was weighted down with 40 pounds of rock—and blew it over my truck. In a flash, the canopy took down my 40- by 60-inch painting, bending my aluminum easel on the way to the ground. The painting and all its impasto fell face first into the dirt.

In five seconds, it seemed, a day’s worth of work was lost along with $1,000 of equipment and supplies. Before I could even attempt to recover the splayed-out painting, I had to untangle the mess of weighted bags, bent poles, and broken canopy parts. The canvas, amazingly, wasn’t punctured—but it had gained a number of indentations, along with a coating of soil, pebbles, and random bits of twig and leaf.

Shortly thereafter the storm hit full-on. First rain and then lots of hail and more incredible wind, the kind that knocks over semi-trucks. I became a frantic blur, hurling everything into the back of my truck as thunder clapped and tiny clumps of ice fell from the sky. Back in the studio I cleaned up the mess and eventually was able to finish the piece. And it’s one of my favorite storm paintings—because it’s a good painting as much as because of the experience, but it’s tough to separate the two because they seem to sustain each other.

Dudley Zopp: I still have a traditional idea of the plein-air painter and feel that I don’t really fit the mold, since I prefer to paint in the studio while referring to sketches and notes done outside. However, I like to capture as much of the living breathing natural world as I can, so perhaps the end result is the same. These two watercolors were done in full view of the rain garden outside my studio door but in other seasons and using iPhone photos as references, The structure of the rocks is a constant. Maybe one of these days I’ll devote at least a season to painting outside. Right now, I like the expansiveness of my painting tables, the elbow room of my studio, and the practice of working on more than one painting at a time.

Valeri Larko: All of my landscapes are painted on location. I spend hours roaming around an area until I find something that resonates with me. Once I do, I set up my easel and return to a site many times. A large painting can take up to three months to complete. I work on one painting in the morning and another one in the afternoon because of the changing light. The process of painting on location over a long period of time is crucial to my working method because it allows me to form a deeper connection to a particular place through careful observation and personal interaction with the people I meet there.

Although my paintings are very detailed, I am less concerned with reproducing an exact documentation of a scene and more interested in capturing the spirit of a place.

For the past 14 years I have been painting in the outer boroughs of New York City, primarily in the Bronx but also in Brooklyn and Queens. Throughout my career I have been interested in industrial sites, urban waterfronts, and more recently the graffiti-laced buildings that are quickly disappearing in the fringes of the city.

Top: Valeri Larko painting on site at the Bronx Golf Center, NY, 2017 (photo by Amy Regalia)

beautiful work thanks

I’d like to share to any and all plein air painters a tool you might find useful. It’s an easel with palette holder that attaches onto a tripod. Super lightweight, compact and inexpensive. It can be found at http://www.LederEasel.com.