The last few years have witnessed a surge of interest in the women of Abstract Expressionism, a loosely affiliated group of artists who came of age in the shadow of the male titans of the movement—Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock, Robert Motherwell, Mark Rothko, et al. “The Women of Abstract Expressionism,” an uneven but widely noticed show at the Denver Art Museum in 2016, seemed at the forefront of a wave of biographies and exhibitions dedicated to individual painters, culminating last year in Mary Gabriel’s irresistibly readable Ninth Street Women, a sweeping history of the period that looked at the lives and works of five women painters: Helen Frankenthaler, Grace Hartigan, Joan Mitchell, Lee Krasner, and Elaine de Kooning.

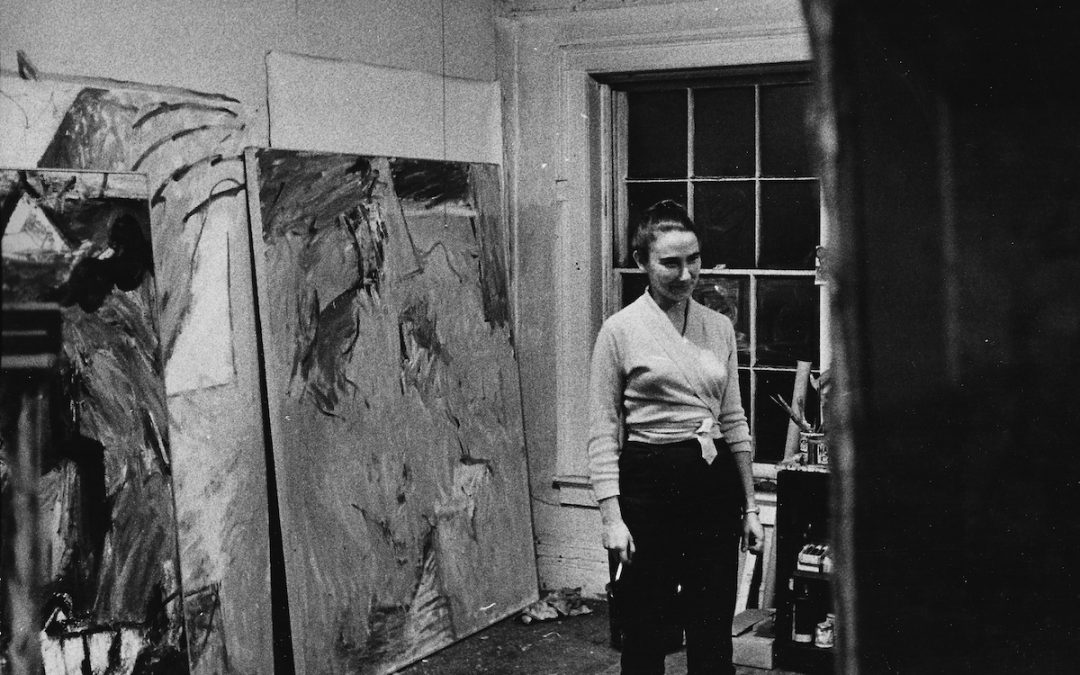

Somehow lost in all this commotion was the fine and fearless Pat Passlof, a painter who was the exact contemporary of Frankenthaler and probably as renowned a teacher as Elaine de Kooning. That oversight is being remedied by a show of the artist’s works called “Pat Passlof: The Brush Is the Finger of the Brain” at the Milton Resnick and Pat Passlof Foundation at 87 Eldridge Street in New York. Organized by critic and independent curator Karen Wilkin, the show and its handsome catalogue document “the story of a determined, daring, and talented young woman in an era dominated by chest-beating male painters and sculptors,” as Wilkin puts it in her essay on the artist.

Passlof was only 20 when she saw de Kooning’s first exhibition, at the Egan Gallery, in 1948, but then and there she determined to learn what she could from the rising star of AbEx. She quit college to enroll at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, acting on a hunch that de Kooning would be teaching there. He was, along with Josef Albers, Buckminster Fuller, and Merce Cunningham. After her return to New York, she became de Kooning’s private pupil for two years—until her parents insisted she earn a real degree and she enrolled at Cranbrook Academy in Michigan.

After graduation, she again gravitated to the downtown crowd and the neighborhood that included so many of the leading artists of the day, who, writes Wilkin, “gathered at the Waldorf Cafeteria, the Cedar Tavern, the Club, and the sidewalks outside them…for intense discussions…about authenticity , the necessity of abstraction, the role of the unconscious, and the artist’s obligation to reveal the unseen….”

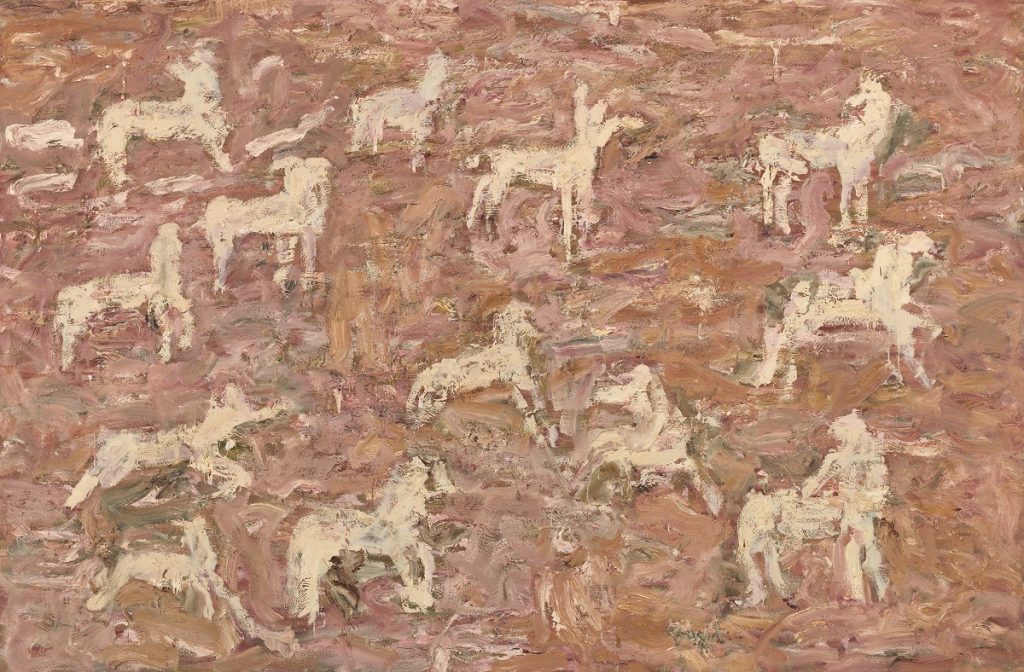

From de Kooning, Wilkin says, Passlof learned the importance of drawing (he had a rigorous academic background from his student days in Rotterdam) and “how to translate perception into mark making.” She was not, however, making imitation de Koonings. From a young age she determined her own course, which would lead her down a number of provocative pathways so that it is hard to pinpoint a definitive Passlof “style.”

It was de Kooning who introduced her to Milton Resnick, a painter and theorist a decade older who had spent two years in Paris on the GI Bill. “She was intensely devoted to him,” says Wilkin, but theirs was a complicated union. They lived together beginning in the mid-1950s, married in 1962, separated in the 1970s, “but remained attached and closely

involved in each other’s work,” Wilkin notes. They lived separately, working in neighboring synagogues converted to living quarters and studios.

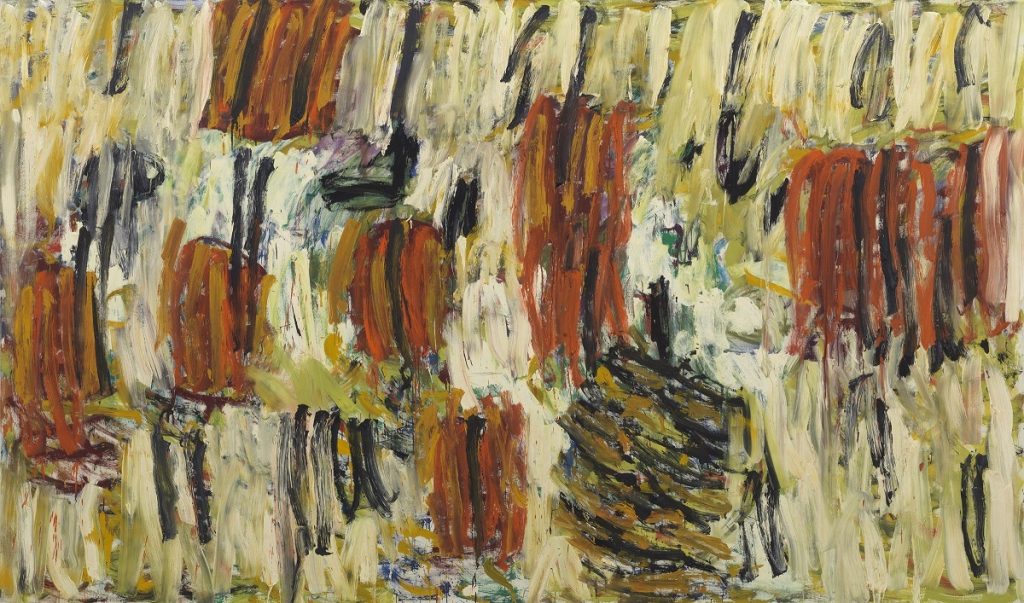

There are affinities in the works of the two—a predilection at certain points for figuration and at other times for all-over abstract compositions. In contrast to de Kooning’s “wet-into-wet , layered efforts,” Wilkin notes, “both Passof and Resnick allowed even their most densely layered brush marks to remain distinct, offering a visible record of the act of depositing pigment on a surface, testimony to both spontaneity and assurance.”

Though many of Passlof’s paintings in both the show and catalogue can seem at first blush superficially dissimilar, the curator points out that there are constants at work throughout her career: vigorous brush marks, energetic calligraphy, a celebration of the sensuality of thick paint, and “a memory of the grid that seems to haunt even her most off-kilter compositions.” Passlof never started with a preconception, says Wilkin. “She always responded to what the paint would do.” Hence her somewhat enigmatic but haunting observation that “the brush is the finger of the brain.”

“The way she applied paint is always part of the meaning of the picture,” says Wilkin.

Passlof was also a memorable teacher for nearly 40 years, at the City University of New York on Staten Island. “I have now heard from at least four students the phrase ‘She changed my life,’” the curator notes. “She managed to convey to them the need to commit to what you are doing. To take it very seriously.”

And that’s a lesson that should endure for the ages. “Pat Passlof” continues at the foundation through April 11, 2020.

All images courtesy of the Pat Passlof and Milton Resnick Foundation. Top: Pat Passlof in her 10th Street studio, c. 1958 (photo: Jesse Fernandez)

I love this article. As usual, full of food for though.

I hadn’t heard of Pat Passlof—such an interesting story. I would love to see more of her work. Guess I should buy the catalog!

I’m also intrigued by her life story. I’m now so curious to learn more about her relationship with Milton Resnick, so intriguing how artist couples work out (or don’t) the intersection of love and competition…I hope a writer does take it upon themselves to write a biography (you???).

I also wonder if she hadn’t been teaching and obviously putting tons of time and energy into her students, whether her art career may have taken off during her lifetime.

Thanks, Barbara. Passlof and Resnick are both wonderful subjects for a biography, but I’ve got enough on my plate as is!

Your article about Pat Passlof was inspiring – sobering too, that an artist of her vision was not recognized until now. Inspiring because she stuck to her vision with integrity, despite the lack of acknowledgment from the Art World.

I see a commonality between her painting ethos and Susan Rothenberg- visceral and honest .

Thank you, Ann!

Thanks for this piece spotlighting Pat Passlof. Her shows over the years at Elizabeth Harris Gallery were always gratifying to behold, and the Foundation is proving to be a treasure.