Why and How a Catalogue Adds Cachet

In an era when vivid high-quality images can be accessed in a nanosecond on almost any available screen, why bother with something as cumbersome as a hard-copy catalogue with glossy images and real pages? Because the tangible can have, well, intangible benefits. ”A book that you can hold in your hands with good writing and images is significant,” says Michael David, who is both a painter and the co-director of David & Schweitzer Gallery in Brooklyn. “In terms of long-term presence that goes beyond the show, it’s very valuable.” Valerie McKenzie of McKenzie Fine Art on the Lower East Side in Manhattan calls catalogues “a great sales tool.” And Liz Garvey of Garvey/Simon, also in New York, adds that it’s important to “document an exhibition, important for future provenance and pedigree, especially as an artist’s career grows and develops a secondary market.”

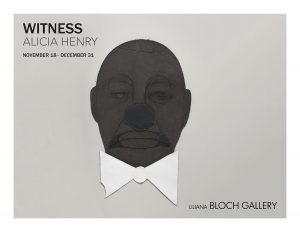

What form a catalogue will take varies from gallery to gallery (and among artists who self-publish). Liliana Bloch of the eponymous gallery in Dallas, TX, forgoes hard-copy catalogues entirely and sends out PDFs to curators, art historians, collectors, and critics. “We create one for every one-person show because we work with curators from out of town, from other cities and countries. That’s the beauty of the internet—we can have a bigger audience.”

Who picks up the expense will vary from dealer to dealer. Some ask artists to foot at least some of the bill, if not all. “I’ve always split costs with artists when I’ve produced catalogues,” notes McKenzie. “However, many artists who teach can get grants from their universities to cover the entire cost.” It used to be that printing an attractive catalogue could run up to $20,000 or $30,000, but with the numerous publishing platforms available, that tab has come down considerably, to as little as $8 to $20 per copy, depending on how many are ordered and what other services, like graphic design and writers’ fees, are needed.

Do It Yourself

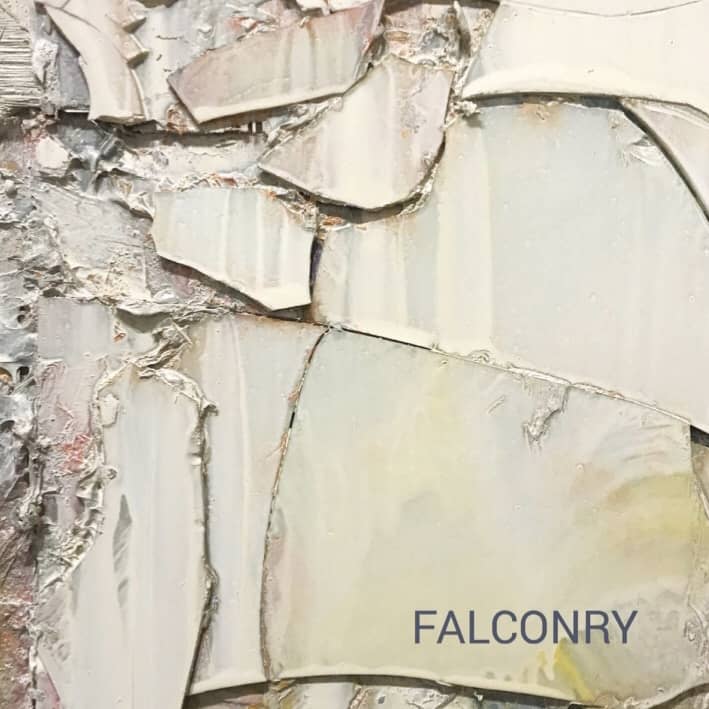

If a gallery chooses not to document your exhibition or your art, you can turn to self-publishing. Kate Petley recently decided to showcase a body of eight paintings in a catalogue. “I want something I can hand to someone that is a real thing, that does not require some kind of device. I don’t think of it as a sales tool. It’s more about building relationships and starting conversations, like going back to writing letters as opposed to sending emails.” And it’s a gesture that shows a certain seriousness about your career.

“I’m going to do two things—the catalogue itself will go in the mail to my collectors and to consultants I’ve worked with over the years, and also to galleries I work with to have on hand,” she says. “And I’ll recreate the catalogue digitally and send it via email to select people on my mailing list.

“The beautiful thing about self-publishing is that it’s not that expensive,” she continues, “and I can control how many I print and make whatever changes I want.” She uses a platform called MagCloud (do a search and you’ll find many such services on the internet) and is including, in addition to the images, a couple of essays, an installation shot from Robischon Gallery in Denver, CO, and a “casual photo” of herself. When she has a show next month at Orth Contemporary in Tulsa, OK, she can swap out photos. “If I’m traveling to a city where I’m having conversations with dealers,” she adds, “I can easily drop off a catalogue.”

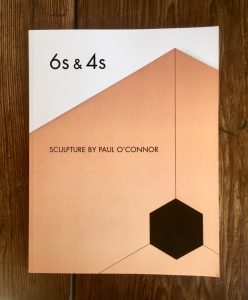

Paul O’Connor, who has worked for most of his career as a photographer, has simultaneously turned to sculpture in the last two decades. After he had a show at Bareiss Gallery in Taos, NM, in 2016, he put together a handsome catalogue containing images of recent work along with a couple of reviews (one of which I wrote for The magazine in Santa Fe—and, no, in general you do not pay the writer for that privilege, but you do ask the publication for permission).

The effort paid off almost immediately. On a visit to Los Angeles, he showed the catalogue to one dealer, who was sufficiently impressed to contact a colleague in New York, who is now showing O’Connor’s work. He made a sale to a collector in Beverly Hills, on the same trip, after showing him the book (he also happened to have a sculpture in the trunk of his car). And passing out copies at the art fairs in Miami last year could lead to a future exhibition in Zurich.

Table of Contents

What you choose to include, aside from high-quality images of the art, is up to you and your dealer, if you’re working with the gallery. “I like to see essays, along with a short selection of publications and exhibitions,” says Michael David. “And it’s nice to have a shot of the artist working in her studio. Don’t try to fit too much stuff in.” You might want to add an abbreviated CV and artist statement, along with a list of collectors.

As for the images, these should be the best you can afford. Both O’Connor and Petley are expert photographers and shoot the work themselves (Paul has offered tips for DIYers in a podcast with me). If your talents are wobbly, consider hiring a pro or asking a talented friend to do the honors. And be sure the images include a caption with title, date, medium, and size. (This sounds patently obvious, but I’m always surprised to see brochures, catalogues, and other printed materials with no information.)

Having written scores of these, I have very decided opinions on catalogue essays about the artist. As readers know from one of my Editor’s Notes, I’m not fond of windy academic writing, arcane references, and a boatload of footnotes. Since writers are often paid by the word, I’m wary of “padding” too (you’ll spot this when the hired pen is repeating the same thing in different words or adding unnecessary quotes). Whether I’m writing an overview or an essay focused on a specific body of work, I like to place the artist within the continuum of art history, if possible, and add biographical details, if relevant. (Did you move to Rome and the art and architecture inspired your vision? Did you study with Joseph Beuys and his philosophy became subsumed into your own?) I try to imagine an audience of intelligent readers who are not intimately conversant with art, and I don’t believe essays should be more than about 1,000 words (museum catalogues, written by scholars and curators, are another matter entirely).

Don’t expect a “name” critic, affiliated with a top-flight newspaper or magazine, to write about your work (though you can always ask). Their publications probably preclude or limit extracurricular assignments, or the writers may not have the time or enthusiasm. Freelance art journalists—and there are many good ones out there—generally charge $1 to $2 a word, and if you need recommendations, ask me. That’s part of why I’m here.

A cheaper way to go, as mentioned above, is to ask your dealer to offer a brief introduction. Or prevail upon poet and novelist friends to write you a blurb. It’s great to have a few words, but it’s the images and your history that count the most.

So keep it beautiful and keep it professional. And bear in mind that a catalogue is a much more meaningful souvenir than a business card, and far less likely to land in the circular file.

Ann Landi

Top: Dallas gallerist Liliana Bloch with artist Bret Slater

As usual, receiving your Vasari21 email blast was perfect timing. Thank you, Ann!

Thank you Ann. I am working on a catalog documenting my recent grant project and considering another one in the near future to highlight a new body of work. Perfect timing for this article and a lot of good information included!

My first attempt at a digital catalogue for a show last fall.

https://issuu.com/mimichenting/docs/willing_to_fly_catalogue

Great information, Ann! Something definitely to add to my to-do list!

Ann, thank you for this very timely article. I just self published a catalogue to accompany my exhibit Dwellers on the Threshold, which opens 4/6 at David&Schweitzer Contemporary. I had design help from another artist and published through Magcloud. I kept it simple and spare, just images, essay and bio. I’ve gotten feedback already on the value of having an informative essay that helps orient the reader/viewer to my work. For me it is wonderful to have a tangible record of the exhibit. Here’s a link to it. https://davidandschweitzer.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Mary_DeVincentis-Catalogue-DSC.pdf

I didn’t see mention in your essay on catalog printing them with amazon self publishing (https://kdp.amazon.com/en_US/) I have done a number of catalogs and one childrens book with them. (https://www.janetmorgan-art.net/shop). The set up is free (a pdf interior and a jpeg for the cover) and then you can purchase up to 999 “author’s copies” for cost, which for a full color 8.5 x 8.5″ 50 pages can be around $5-6 . I did this one for a three woman show at Omega https://www.amazon.com/Quintessence-Three-Visions-Janet-Morgan/dp/1497431212 and the for first big show I curated I did this one with Artfront Galleries in Newark https://www.amazon.com/Divine-Feminist-Janet-Morgan-MFA/dp/1798161524/