I’m a sucker for big abstract paintings and for collages that remind me of the contemporary art I fell for hard decades ago (as I wrote in “First Love and Irresistible Impulses”). Video has to engage me within five minutes or so or I’m outta there. I’m not a big fan of the Flotsam and Jetsam School of Sculpture exemplified by artists like Rachel Harrison and Helen Marten (but of course I defend their right to make it). Conceptual art doesn’t do much for me, and I never, ever understood John Baldessari.

But of course I tried and still try to remain open to whatever crosses my path and concede that maybe in time these artists will look better to me. Knowing my own predilections when I’m out and about in galleries and museums (or even just looking online), I was curious to learn if other critics were of aware of similar proclivities. Or simply wanted to talk about what really bowls them over..

And here’s how they responded:

I prefer the word “prejudice” to “bias” because the former describes the problem literally, judging something in advance of seeing it. Such judgments are not necessarily wrong, but they have the distinct shortcoming of being unconfirmed by actual looking. A lot of looking at art will inevitably bring you to the day that your judgment conflicts with your prejudgment. How a critic responds to that conflict is the mark of his worth. A good critic will allow his taste to surprise him, and report on that honestly. A bad critic will talk himself out of his honest response and write according to how he thinks he should have responded. There are critics, even prominent ones, who have spent so much time talking themselves out of their real responses that they have ruined their taste. That’s granting that they had some to begin with.

Prejudices are preferences run amok. Preferences themselves are inevitable and natural. I’ve thought a lot about painting, and I’ve tried to make a lot of different kinds of painting, which is not something I can say about, say, video art. Consequently, I’m better on painting than video art. If it falls to me to write about video I’m careful to make sure that I’m not missing anything basic and I try to err on the side of generosity. I’m indifferent to the indigenous art of North America, which I can’t explain because the indigenous art of South America is fascinating, so I just don’t write about it–obviously I’m missing something. Then there’s conceptual art, which we’re allowed to dislike categorically because it is a categorical exercise to begin with, making a given thing into art by defining it as such and presenting it as such. But it’s important not to pan work you dislike categorically because it usually makes for boring copy. Writing about it sometimes means giving the devil his due.

At any rate, the goal is to pass judgment on the art. This is becoming increasingly impossible, largely due to diminishing opportunities to write about anything. But also, the idea that everything is political, which is wrong, has nevertheless been gaining ground in the arts for a long time. This would be an unfortunate development anyway, but the arts are already a political monoculture, and it results in art judgments disappearing into a background haze of foregone political conclusions.

Franklin Einspruch is an artist in Boston and the editor-in-chief of “Delicious Line.” His reviews appear regularly in The New Criterion,

Karen Wilkin

There are artists I’ve been interested in for a long time, whose exhibitions I follow. Sometimes they are artists whose shows I’ve organized or written about extensively because I find their work so compelling. For some, I’m a fairly regular studio visitor. Some of those whose studios I used to frequent or whose shows I’ve worked on are no longer alive and that makes seeing their work especially moving and poignant.

But particular kinds of art? Hard to say. I’m usually bowled over by Romanesque art. (When I was about 20 and in France for the first time, I kissed a sculpture of a male saint from Autun. There was no one around.) Indian and Islamic miniatures fascinate me, as does a lot of Indian sculpture, but I tend to be indifferent to a lot of historical Asian art, probably because of ignorance. I’ve never gotten Russian Constructivism or Latin American geometric art, which is obviously a sign of some kind of perceptual deficiency, but it bores me to distraction. And there are certain artists whose work makes me want to run screaming from the gallery whenever I’ve come across it.

But there’s nothing better than being engaged by something unexpected. I try to approach work without preconceptions and spend enough time to come to terms with what I’m presented with. Sometimes there are wonderful surprises. I found myself unable to leave a Douglas Gordon video and stayed with it for the entire three hours. The guards were looking at me very oddly.

But there’s nothing better than being engaged by something unexpected. I try to approach work without preconceptions and spend enough time to come to terms with what I’m presented with. Sometimes there are wonderful surprises. I found myself unable to leave a Douglas Gordon video and stayed with it for the entire three hours. The guards were looking at me very oddly.

I don’t think I have particular biases against media, although I am highly critical of a lot of contemporary sculpture that is made of appropriated stuff from the real world; if the stuff isn’t transformed by its new context, but simply remains — say — a length of orange plastic snow fencing, it’s game over for me

Bottom line: there’s no such thing as objective criticism. If you believe Immanuel Kant, value judgements are involuntary and not subject to persuasion, so we’re constantly saying yes or no to what’s in front of us, no matter how open minded we try to be. One can fall back on describing the work in question, but is that criticism?

Karen Wilkin is an independent critic and curator who writes for The Wall Street Journal, Hudson Review, and The New Criterion. She also teaches in the MFA program at the New York Studio School. (Photo by Grace Roselli)

David S. Rubin

Certainly I do have biases, but overall I am a pluralist. When I worked on theme shows as a curator, I often included work because it really fit the project, even if it wasn’t necessarily my cup of tea. As long as it was competent or significant in some way, I would include it. Writing reviews is a bit different, however. At this stage in my life (as a senior), I’m really not interested in reviewing something unless it interests  me. Particularly working in Los Angeles, where there are so many options, I prefer not to write about anything if I find it dull, not up to a certain level of skill, or perhaps too hermetic. My approach as a reviewer is really to ask, “What’s in it for the viewer?” Also, I’m not interested in writing negative reviews, since I have no desire to cause a curator or artist any grief. Rather, where possible, I like to give artists who are doing good work a boost. As a pluralist, I’m open to any genre or medium, but it does have to motivate me first. My basic criteria for curating definitely applies in deciding what to review. I ask four questions: 1) Is it visually engaging? 2) Does it have a fresh and unfamiliar edge? 3) Is there a fair degree of accessibility? 4) Is the work relevant to the time in which it was created?

me. Particularly working in Los Angeles, where there are so many options, I prefer not to write about anything if I find it dull, not up to a certain level of skill, or perhaps too hermetic. My approach as a reviewer is really to ask, “What’s in it for the viewer?” Also, I’m not interested in writing negative reviews, since I have no desire to cause a curator or artist any grief. Rather, where possible, I like to give artists who are doing good work a boost. As a pluralist, I’m open to any genre or medium, but it does have to motivate me first. My basic criteria for curating definitely applies in deciding what to review. I ask four questions: 1) Is it visually engaging? 2) Does it have a fresh and unfamiliar edge? 3) Is there a fair degree of accessibility? 4) Is the work relevant to the time in which it was created?

David S. Rubin is a Los Angeles-based curator, writer, and artist. His curatorial archives are housed in the Smithsonian Institution’s Archives of American Art. Rubin recently organized the nationally touring exhibition “Salvador Dali’s Stairway to Heaven.” He currently writes for Visual Art Source and Art and Cake, and he will have a solo exhibition of his drawings at California State University Northridge Art Galleries in the fall of 2020.

Kim Levin

I have a proclivity for art that is unexpected, unpredictable, and goes to extremes. I like to be astonished—in a good way. I gravitate toward art that is unlike anything I have ever seen before. Art that attempts the unimaginable, that breaks whatever rules the art world of the moment has imposed, that questions assumptions and raises new issues.

Such as, a long time ago, Mudman (aka Kim Jones), a former marine in Vietnam, caked with mud, sporting a backpack of branches and twigs, stationed on West Broadway near the old Mary Boone gallery.

Such as David Wojnarowicz’s first amazing solo in a small storefront gallery in the East Village.

Such as Sarah Sze’s early installation of bits and pieces hiding in corners at PS 1 years ago, or Pipilotti Rist’s hole-in-the-floor video of herself seen from above.

Pope.L’s earliest “crawl” up Broadway. Andrea Fraser’s daring Official Welcome of herself using nine different institutional voices to welcome herself while shedding her clothes, or Maurizio Cattelan’s solid gold toilet at the Guggenheim. To me, astonishing works such as these are the rewards of being an art critic on the front lines, where we function as primary sources. I place my trust in opinionated choices and unconditional love of difficult work. I leave the pretense of objectivity to the art historians.

Kim Levin is a former critic for The Village Voice and the author of the forthcoming volume of essays, ELSEWHERE: The Tainted Garden and Other Essays on Art, Life, and the Anthropocene.

Peter Plagens

The Number One priority for me is the reader; she/he has to get what my opinion is, and to be gotten, the opinion has to be delivered in understandable prose, it has to be backed with pertinent facts, and it has to be reasonably well-argued. All in less than 1,000 words, which is the usual limit general-interest publications. Being “fair” to the artist, the work, or the show is secondary. Of course, if I’m blatantly unfair, it’ll show up in bad prose, bad facts, and bad argument.

No critic comes completely unbiased, but bias is tricky. I’m a painter, and I favor, for my own enjoyment and contemplation, painting and sculpture that stands still. That often means, however, that I’m harder on painting and stand-still sculpture because I’m closer to them. With some paintings, I can feel the moves the painter makes, and often I can suss the reason the moves were made. Installation and video, on the other hand, can sucker me because I’m more a layperson with those mediums.

OK, now the big question these days: Can an old, straight, white male critic judge art by (chose any two) young, female, LGBTQ artists of color? And since young female LGBTQ artists of color tend these days to be not abstract artists but instead figuratively “addressing” some sociopolitical issue (or some unfalsifiable kumbaya) dear to their hearts but perhaps more distant to mine, how can I judge that kind of work?

I start with the fact that the art is made public, i.e., it’s not some coded communication to a secret society (and it’s not a quantum physics equation that I just don’t understand). Affecting people who might publish their opinions in credible outlets is, I figure, part of why the artist(s) went to the trouble to make the art public in the first place. (Note: No one I can remember has ever complained about a rave review by me because I’m from a different age/sex/sexual-orientation/race/ethnic category than the artist.)

I do watch out for my biases—with a catch. Sometimes obviously exaggerating the aesthetic ones, maybe self-effacingly, makes for a more readable review, which is after all the point (see Number One priority, above). Sociopolitically, my main bias is against inefficiency. (As Samuel Goldwyn said to a screenwriter who wanted to make “message” movies: “Messages, messages,” Goldwyn responded, “From Western Union you get messages. From me you get pictures.”) Occasionally a “message” work of contemporary art (about 63.7 percent of what I currently see more or less qualifies as that) has emotional and intellectual gravitas and transcends being—not to put too fine a point on it—propaganda.

Finally, I understand that nothing is ever really settled, that a review by me isn’t the final word, and that a fruitful argument, from which I might learn something, is the best result.

Peter Plagens shows regularly with Nancy Hoffman in New York, and is a critic for The Wall Street Journal. He has also been a contributing editor of ARTforum and Newsweek, and is the author of the recent monograph on Bruce Nauman (Phaidon). Drawing, above, by Walter Gabrielson.

Peter Frank

I have detected a bias on my part toward work that emphasizes line, especially notational (albeit not necessarily language-oriented) work. I also favor high-quality technique (or “craft” if you will) with narrative painting and drawing, as long as it’s not too slick and showy; if someone wants to make pictures, I want the details to be clear. I’m partial to collage, especially on a small scale, and to geometric work, especially as either method harks back to prewar avant-gardes. I think those are my principal biases.

I have something of an aversion to big heads, especially expressionist ones, and time-based art that lacks a sense of time. The latter is a betrayal of its mediumistic truth, as it were, and the former I find an adolescent trope. But beyond puerility and insensitivity, I allow work that adequately reaches its apparent goal with a mature, self-reflective mastery of substance and concept. The goal is apparent in the work itself. I should mention that I never give much credence to artists’ statements unless I’m digging deep or going long in the writing (as in a catalog essay).

Peter Frank is a Los Angeles-based critic, editor, and curator (currently associate editor of Fabrik magazine). He has been the art critic for LA Weekly as well as for The Village Voice and SoHo Weekly. He was senior curator at the Riverside Art Museum and has organized exhibitions for Documenta, the Venice Biennale, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, El Museo Reina Sofia in Madrid, and other institutions. (Photo by Eric Minh Swenson)

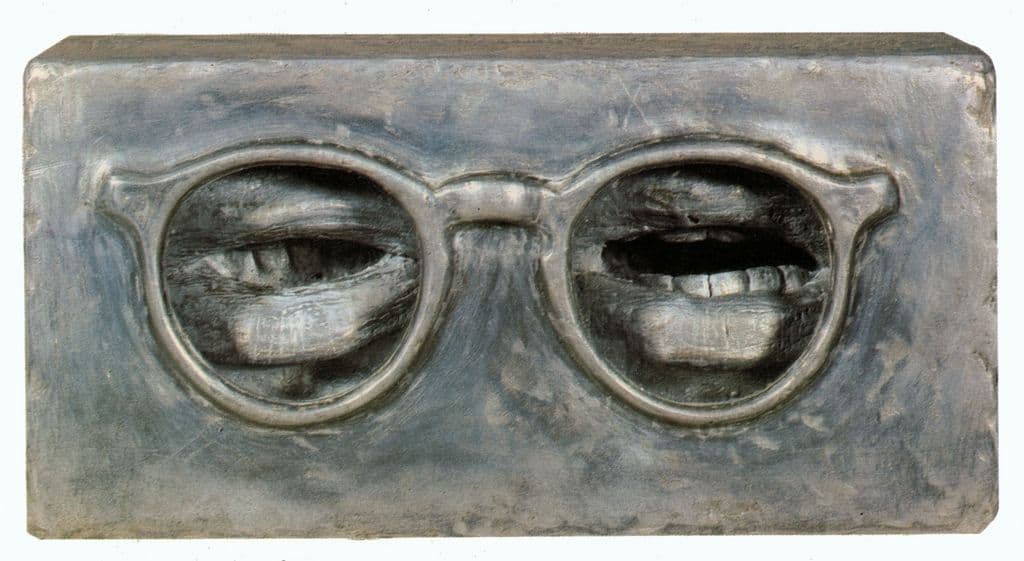

Top: Jasper Johns, The Critic Sees (1961)

–A fun set of interviews to read and, in my experience, often true.

Art writers do have predilections but I think the best art writing continues a public conversation started by the work. That conversation encompasses much of what the art writers mentioned above and, most importantly, it puts the work being reviewed into a cultural context. That is why art reviews are still so needed; a thoughtful, well written review helps us see the art as part of our community(ies)–even if we missed the actual exhibit.

Through the years working as an Artist, I have gotten several reviews, My first reviews for the same body of work shown one month apart were written by Henry Seldis (good review) and William Wilson (bad review), David Rubin wrote a thoughtful review of my “Black Forest” show that helped viewers understand my work, Merle Schipper also understood my paintings and was able to convey this to the reader,

Kristine McKenna wrote a review of my early oils that felt like a personal attack, Though it brought tears of outrage to my eyes, it filled the gallery the next day!

Thomas Albright wrote a sensitive review of my show in San Francisco and New York reviewers conveyed excitement over my early Rhoplex paintings,

I favor honest reviews that help viewers understand my work and give me further insight,

Arrogant reviews that are power-trips are a turn-off,

From an artist’s point of view, I don’t think art is sold because of a review, but it certainly may get a few more people to have a look. And I think a bad review might bring in more people than a good one, on occasion. A videographer did a documentary short on me, which is like a video review of an artists work and life. It became a staff pick on Vimeo and was replayed around the world with 32,000 views in just a week. Did I get any sales off that? No, not one. Now over 40,000 people have seen it. Not one inquiry even.