After five posts, I’m running a bit low on things to say about drawing. But for a moment we might speculate about why drawing remains so popular among artists, when, let’s say, there’s hardly anyone around making frescoes these days. There is, of course, the amazing portability and convenience of drawing: you need only the stub of a pencil and a pad to make a sketch (Picasso used to doodle on cocktail napkins; smart friends tucked them away, knowing their value would skyrocket). Yet simultaneously the possibilities for materials have ballooned (perhaps even including balloons). Take Gelah Penn, for instance, who considers some of her works made from plastic garbage bags, eyelets, staples, and fishing line to be drawings. Or William Norton, who draws on plexiglass with a Dremel. Or Brandon Graving, who uses glue and a natural material known as camwood.

But above all, drawing remains highly valued by artists for its spontaneity and in-your-face “hereness.” As Wendy Goldberg puts it, she values the medium for “its direct and vital connection between seeing and feeling—a brief moment when I’m just taking in what’s immediately before me.” Ann Landi

Wendy Goldberg

Drawing is my first love, for its immediacy, its messiness, its direct and vital connection between seeing and feeling—a brief moment when I’m just taking in what’s immediately before me. Like gardening, I can’t keep my gloves on, and I like getting my hands dirty. I like the sensuousness of chalk or charcoal or compost. I like drawing weather or clouds or the beginnings and ends of the day when the light and atmosphere are constantly changing. Drawing seems the best and the most direct means for achieving this.

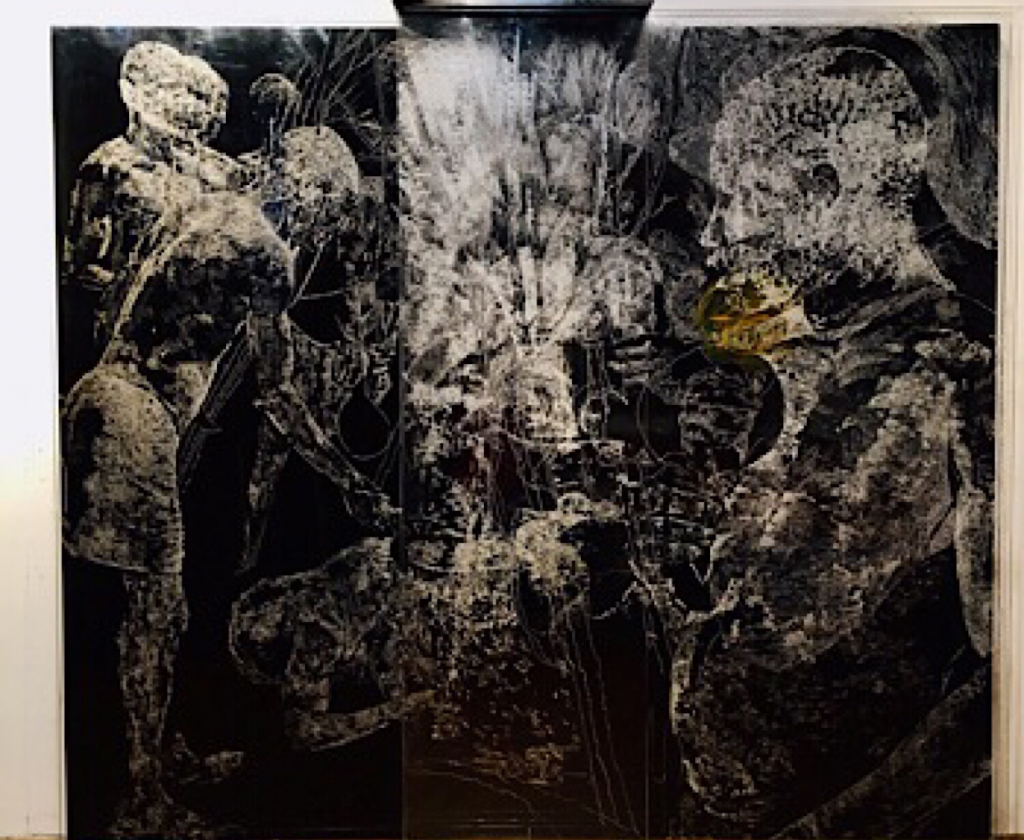

William Norton

All my work is drawn. I carve lines into plexiglass using a Dremel. The resulting lines display as white when presented in front of black. I use the shiny black plexi as a mirrored surface to include the audience as participants in the work. Drawing to me is about how the artist’s vision is immediately available on the surface of a work with no interference.

The subject is a coming-of-age manhood ritual. I was trying to ascertain what it means to be a man when I could not even protect my own son, who years ago was abducted by my ex-wife.

William Norton, Creation Theory: Blood Moon (1999-2018), hand-etched clear plexiglass, 84 by 96 by 7.5 inches

Marcia Oliver

A love of drawing begins early in life. In my case, probably stemming from a natural bent for introspection and solitude. I grew up near a bayou in northwest Florida, where I spent hours alone, exploring the shore, paddling the tributaries, and constructing small

bamboo-grass huts. In school, I preferred to scribble drawings instead of studying. My current pieces that come closest to drawings are a combination of paper scraps, ink, charcoal and pencil, which feed into my larger works on canvas.

Gelah Penn

I continue to examine visual ambiguity through the manipulation of synthetic materials. The notion of drawing as inquiry propels my sculptural drawings, percolating alongside the installations.

Gelah Penn, Ebb Tide, installation at Odetta Gallery (New York), 2019, various synthetic materials, dimensions variable

Annell Livingston

Drawing has been regarded as simultaneously fundamental and peripheral, essential to artistic practice and the most basic skill an artist can possess. Drawing allows the artist to dream the endless dream-making notes along the way. Drawing connects the artist to infinity and eternity; it is a map of time.

My drawings could be seen as pages of a diary or personal journal, and like poetry, one idea dissolves into another and the work becomes a sequence of new images; like each new day, forever changing. Drawing and touch could be thought of as the same experience, only one leaves traces.

Brandon Graving

Glue is one of my favorite drawing materials; I like the actual substance of glue, both for its varied properties and the way I align with it conceptually in this work. In Roux: E, the glue acts to adhere the camwood material to the paper and also functions as a resist to articulate the central form.

Camwood, in its powdered form, is used by women and girls in Cameroon, Africa, which is where I collected it. When a girl is to be married, her friends rub it on her skin for about two weeks prior to the ceremony, and over time it imparts a warm reddish hue, making her skin glow. I have been using it as a component in my work since living in Cameroon for more than three years when I was in my twenties.

This ongoing series called “Roux,” in various mediums, references the act of stirring flour in a pot with butter as the base for sauces; it also resembles an aerial view of a hurricane. I consider it a drawing because it’s made from an accretion of glue marks and gestures realized using the powdered wood.

Dudley Zopp

I’ve always drawn as a way of understanding what I think about things. Nowadays I also spend more time with charcoal and pencil studies, either to parse out the elements of a painting in progress, or just for the pure fun of it. Drawing is a more physical and immediate connection to the natural world. What’s it like to be a garden urn, or a tree? Drawing helps me figure it out. What’s it like to be standing here, looking at the garden urn? I begin my paintings by drawing the spatial relationships, and I keep on using drawing as the primary means of developing the object to its finish.

Dudley Zopp, Garden Urn No. 28 (2013), watercolor and charcoal on Fabriano paper, 13.5 by 15.5 inches

Karen Jelenfy

I am working on a series I’m calling “Cauliflower Heads,” which is a reference to the appearance of the human brain when sliced for dissection. I cared for my father, my father-in-law, and my partner’s grandmother as they each slowly lost their way to dementia. Alzheimer’s disease can only be definitively diagnosed by autopsy. The diseased brain looks like a burnt chunk of cauliflower.

My father died, in my care, of Alzheimer’s in 2012, and the

drawings are based on my own fear of developing dementia. I have been referred to a neurologist. The question becomes: do I want to know? The only way I know how to wrestle with such questions is to draw and paint.

The worst question I have ever had to answer was when my dad asked me, “Is there a name for what’s wrong with me?”

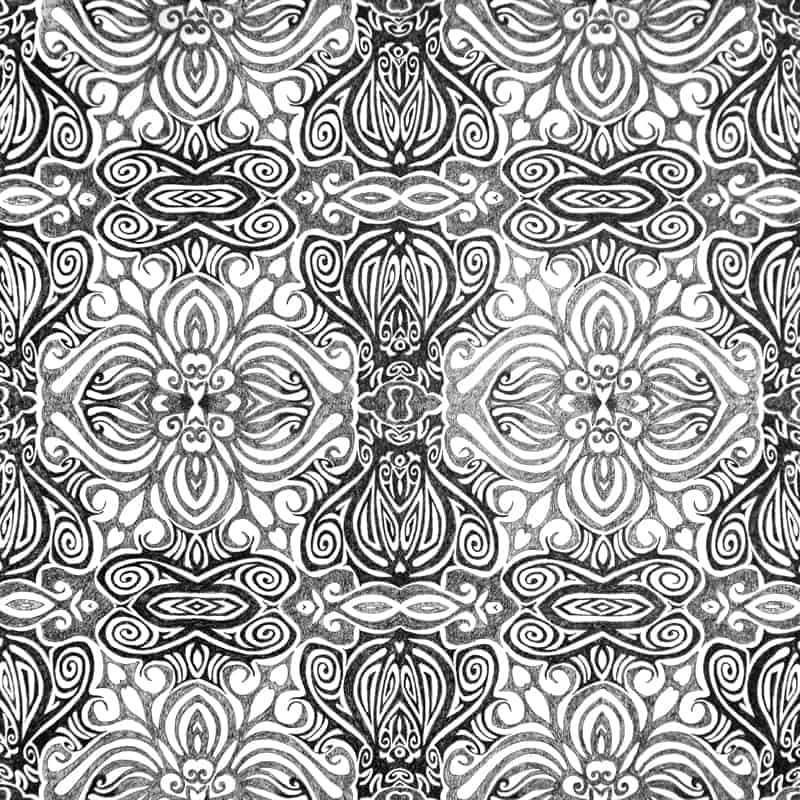

Janet Towbin

My drawings from the “Patterns of Obsession” series begin as very small sketches. The sketches are then refined to a certain point and photographed or scanned into jpegs to work with in Photoshop on my computer. They are further developed through manipulation and repetition to create final patterns I find captivating enough to spend 20, 30, or 40 hours drawing. All drawings are made with a mechanical pencil using mostly HB or F leads on Stonehenge paper.

Drawing has always been a form of meditation for me. There is something very beautiful about making a silvery pencil mark on a sheet of clean white paper. The process of being able to combine deliberate marks into shapes that flow and expand into patterns is quite magical. I love seeing lines come to life as the shapes I draw move and grow, taking on depth and dimension within an orderly, repeating pattern.

I often compare my drawing to knitting, which is also a meditative and magical process. One stitch, alone, isn’t much; but when combined and accumulated with thousands of other stitches in a determined fashion, you have produced something quite lovely.

Top: Gelah Penn, detail from her installation Ebb Tide at Odetta Gallery in New York (March-April, 2019)

Ann, It’s great to see the varied approaches to the materials and processes of drawings here. Thanks so much for including me in Part Six, and for featuring my Garden Urn at the top of your newsletter. “Such stuff as dreams are made on” indeed.

Thank you Ann.