In the third iteration of this series, I noted that the possibilities for drawing have expanded hugely in the last century or so. Picasso made drawings with a small electric light in a darkened room. Calder’s Circus can be seen as an assemblage of three-dimensional drawings made with wire. Andy Goldsworthy’s “Rain Shadows,” in which the artist uses his whole body to create an impression on the ground, could qualify as a way of drawing still using that most primitive pigment—wet dirt.

In these posts alone, we’ve seen drawings made by traditional means—pencil, ink, charcoal, metalpoint, and so on—and a few that are more unconventional, like working with a dremel on plexiglass or pushing sawdust around to make an image. When I put out the call for more (and there will be yet another installment in April, if you don’t see yourself here), even more novel ways of working showed up. How about draping the drawing around trees or using old books as sketchpads or repurposed packaging as a ground?

I want to say the sky’s the limit except I know artists are probably already using contrails as their medium….and I hope to find out more about that soon.

Barbara Marks

I make paintings—but drawing is my habit. I draw every day, any place, and everywhere. Much of my imagery comes from direct observation, but some of my drawings have moved into the realm of memory and imagination. I draw mostly with an extra-superfine black India ink pen, and sometimes with colored ink, in accordion-fold albums. Each album contains one continuous sheet of drawing paper, 8.25 inches high by 123 inches long, folded into a hardbound cover. (I’ve filled 150-plus albums with drawings.) Lately, though, I’ve been drawing on the insides of collapsed and unfolded packaging—formerly containing such ordinary items as bar soap, chocolate, tissues, crackers, aspirin, etc.—upcycling something meant to be disposed of, by re-employing it as the substrate for a drawing.

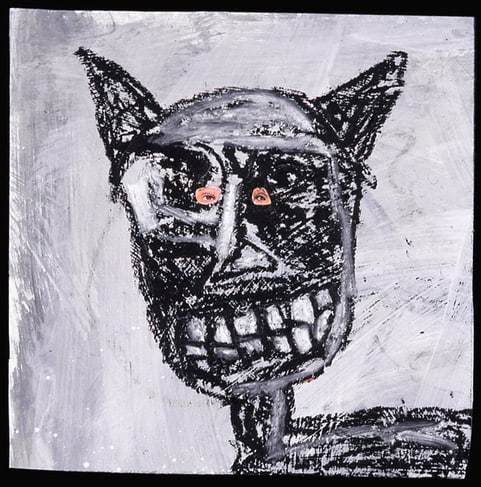

Melissa Stern

Since I was a very young child, I have always made drawings. Many kids do this, it’s not unusual. I found that it was a way to express what was on my mind, often times visualizing things that I couldn’t express in words. The drawings were very private. Fast forward to adulthood. I still drew, and for the same reasons. It never occurred to me to show these works to anyone, let alone in a gallery. People who visited the studio began to remark how my sculptures and drawings seemed to “bounce off” of one another in a very potent way. So I began to show them in tandem with the objects I was making and noted that the drawings, no matter how personal and private I thought they were, seemed to really resonate with people. The ideas in one do indeed reinforce the ideas in the other. I’ve never made drawings of sculptures or visa versa, but together they present a full universe of the ideas and people running around in my brain. I love to draw.

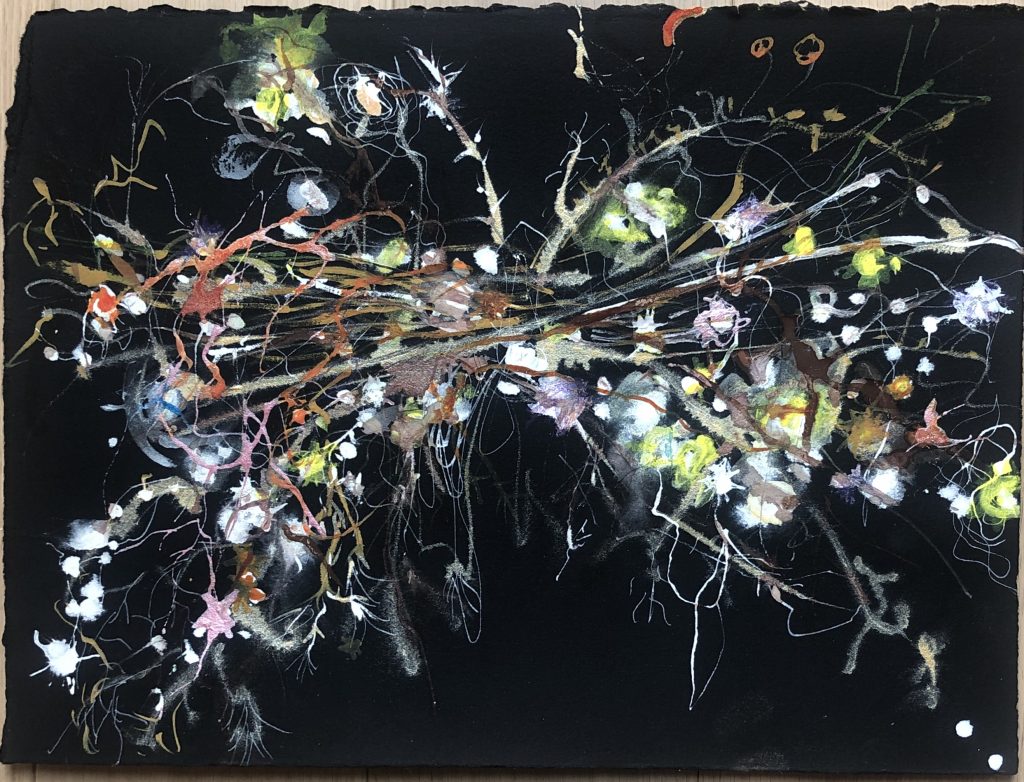

Susan Christie

This was the first in the “Pentimento” series, realized on unique handmade Japanese paper, which has properties allowing me to add layers that appear underneath, over and above each other. (The images emerging through translucent layers reminded me of the original definition of “pentimento”—a reappearance in a painting of an original drawn or painted element eventually painted over by the artist.

It was made during travel with nothing in mind but the pleasure in the movement of the materials and the quiet of the Minnesota snowfall. The “titles” of the pieces followed as another seven were completed. The first painting was an example of “shoshin,” Beginners Mind.

Susan A. Christie, Pentimento I (2013), Asian ink, gouache, and watercolor on Asian paper, 11.5 by 29 inches

Iain Machell

As a Brit living in New York State, I come from an artistic legacy of landscape art. This part of North America is famous for the romantic landscapes of the Hudson River painters like Thomas Cole and Frederick Church. Peel consists of two canvases, each 18 feet long and covered in paint, that poke fun at the romantic tradition of landscape art. Instead of a painting of the landscape Peel is a drawing in and from the landscape. Instead of a mediated experience of nature, filtered through an artistic sensibility and swollen with technique, Peel is a direct imprint from the trees pulled off the surface like a bandage. This is an investigation into the nature of landscape, and into the human depiction of and intervention in the landscape.

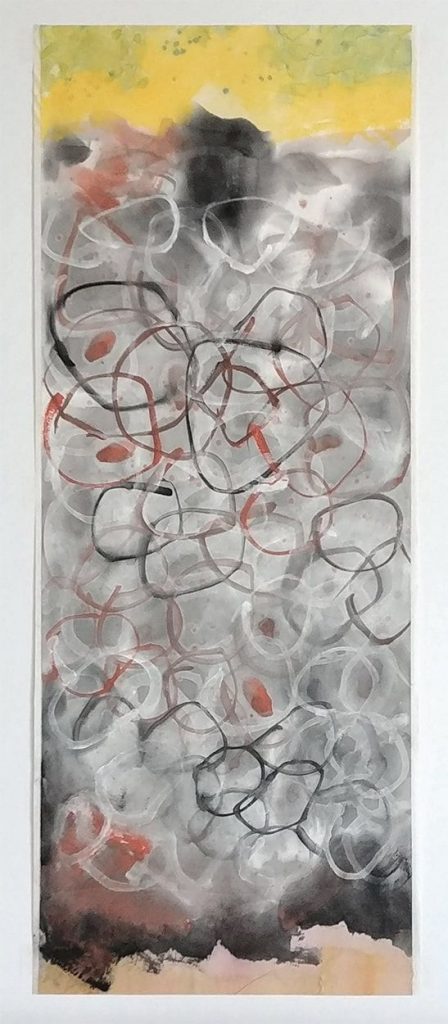

Lizbeth Mitty

My ink drawings both stand alone and serve as preparatory works. When I make a drawing, I don’t know how, or even if, I will use it to inform a painting on canvas. A drawing might hang on the studio wall for months and suddenly, without warning, provide a way to begin or resolve a large piece. It’s like meeting a deceased loved one in a dream, who tells you how to solve your life’s problems.

My preferred way to draw is in ink. I love the flow of the brush and Japanese stick. The line is most beautiful on thick handmade paper. Sometimes these drawings are multilayered and closer to small paintings. I allow them to become whatever the process brings, whether a study or a small painting. The multilayered ones often involve more work than a very large painting, and they can become quite rich and dense.

Rita Grendze

When circumstances dictated, I moved my studio to a small converted garage, and daily drawings became my transition from family responsibilities to studio work. In some ways, these quick, intuitive sketches have replaced my former commute, allowing me to assess the tasks ahead, observe shapes, patterns and colors in my studio and yard, and to really gain focus. I started drawing on Arches paper, but soon made the switch to working in a cast-off book (left over from an installation), using my son’s art-class watercolors to keep the small drawings from feeling precious. One book became two, then three, that are worked on simultaneously. The type on the page adds texture, and acts like a prompt to get me started. This practice has led to a parallel series of observational sketches for my next installation, which I call on Instagram @theworkingfromhomeproject.

Margaret Zox Brown

I created this piece in 2015. It was one of the first of my mixed-media pieces on paper. I had discovered the Conté crayon and realized that this is an excellent tool for me, allowing me to really hone in on the nuanced details of my subject and create a full, beautiful drawing that has a broad spectrum of gradations of dark. I then added paint in select spots, creating what I felt was and is an abstract piece. There is drawing, there is blank paper, there is paint with varying textures from thin to thick. This boy is a muse I have used in several paintings. The beauty of his face and the raw innocence of his spirit were unearthed by the Conté drawing and then enhanced by addition of paint.

Margaret Zox Brown, Pondering Red (2015), Conté crayon and oil paint on deckled paper, 22 by 30 inches

Meghan Wilbar

Drawing is a meditation on what is seen by the eyes and the mind. I’ve been drawing for years in the landscape and always find solace and surprise. Landscape tells a story of our brief moments of time, place, and experience. I’ve been drawing the intimate story that exists by looking into the vastness of the open road and selecting the story through torn paper and drawn line.

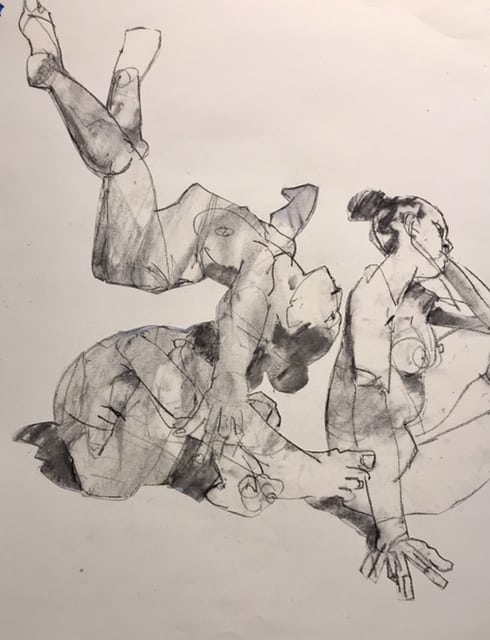

Bob Richardson

I’ve drawn from models forever. I like the quick sketches. I draw on top of drawings. I like to erase. I like all the energy. I also like the single line…the quality of line, the elegance. So recently, I started culling out 50 pads of life drawings, thinking I’ll throw away the bad and put the rest back into eternal storage. While doing this, I see all these drawings, some with good bones, each on their own page and for the most part with no story. Complete them. Give them the story. Whatever that means. So I start cutting them out. I isolate the figure from all the clutter. I collage them. I move them around. I create dialogue. It’s been an exciting couple of weeks.

Carol Ladewig

I clipped a photo from the New York Times of Rabin and Arafat in 1993, enlarged it, and drew from that. I keep it in my studio as a reminder that amazing things can happen, and we go forward and backward.

Ellen Jouret-Epstein

I’ve drawn at different times in my life, although usually as a form of warm-up or work-out. But a few months ago I was struggling with the direction of my work—some ways of working were exhausted, others began to feel just too laborious. I needed to reclaim the flow and fun. I’d been doing collage, and so that became the starting point for a group of drawings. This way of working leads me back to the playfulness, layering, complexity, and mystery that I love to find in my work, and with that comes kind of flow that other materials and processes just don’t give me.

Ellen Jouret-Epstein, Web Series #2 (2018), colored pencil and acrylic drawing on printed paper collage; 15 by 17 inches.

Tracey Adams

Drawing is immediate, spontaneous and intimate. It need only exist for itself and for no other reason than that. Comparable to a haiku or a folk song, drawing captures a moment in time, best when kept simple without over-thinking the process.

Top: Meghan Wilbar, The High Road (2018), mixed media, 24 by 55 inches

Thank Vasari 21!

This has been a terrific series of posts. I seen the work of many terrific artists whom I wasn’t familiar with. Fascinating to see/read where so many different drawings are coming from.

Love the work shown, thank you! Would love to be considered for another time.

Louise Kalin

Really fun to see so many approaches to “drawing”. which I consider a

prelude to painting.

Such an interesting read, THANKS to Vasari21 and the contributing artists.

Freedom! Fascinating to read a multitude of interpretations, the variety of materials, and the opportunity to reuse what one previously created.