In this, the eighth round-up of drawings from members of the site, I find myself running out of more to say about this oldest means of making an image. And yet even if I fall short on words, the artists never cease to amaze me with new ways to make a drawing. (Stitching anyone?)

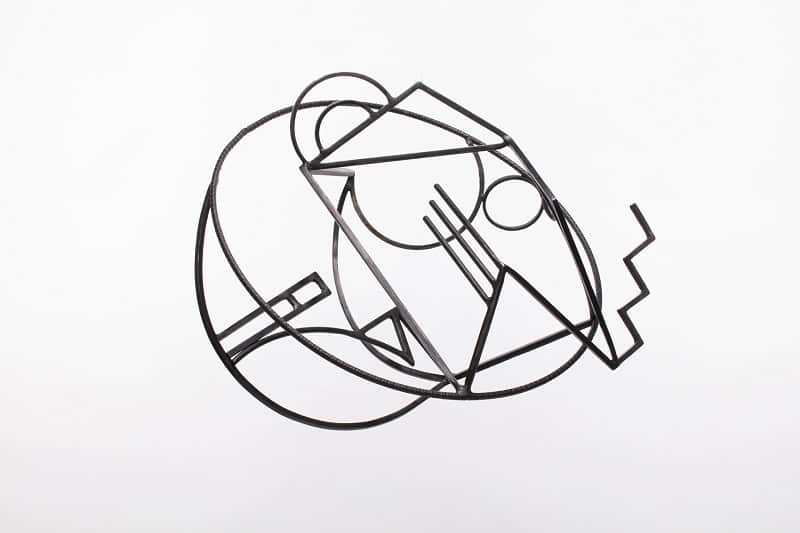

I’m surprised, too, that even though the concept of “drawing in space” has been around since Spanish sculptor Julio González articulated the idea in Cahiers d’Art in the 1920s and ‘30s, only one sculptor so far—Susan Bennett—has brought the practice up to the present. (I’m sure there are others out there, and I hope I hear from you because it’s a nifty way to extend the practice of using line to define space.)

It seems inevitable, in these difficult and uncertain times, that many of the artists here are using drawing as a kind of record keeping. “I am drawing while I live, incorporating where I am, what I am thinking, what I remember, or imagine,” writes Alyse Rosner. “These pieces are unfiltered, direct output—as honest as I can be—apparitions, veils, obstacles and simple marks that are blueprints of my stream of consciousness, reflecting the uncharted territory we find ourselves in.”

Martha Wakefield: The sketchbook is an important part of my studio practice. I use these pages as a warm-up before embarking on other work-in-progress. This practice helps me to center myself in the space as well as play with the many tools and materials in my studio. It is important playtime. I use the Strathmore 500 series mixed-media art journal—whose individual pages measure 9.75 by 7.75 inches—because the paper stands up to all media. My postings of my sketchbook pages on Instagram (Instagram.com/mmwakefield) led to invitations to jury a show on sketchbooks and also to create a class titled “Embracing the Sketchbook,” which I have now taught several times.

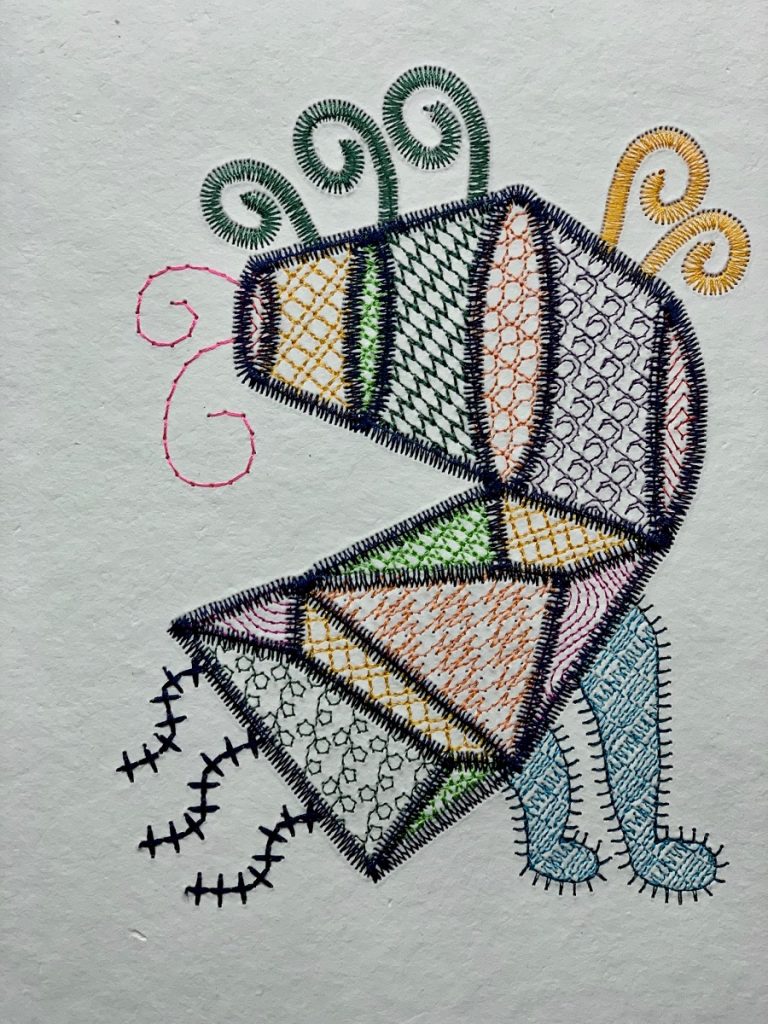

Leslie Giuliani: After spending decades drawing in the traditional way, with charcoal, I wanted to remove the “hand” from my drawing practice. I felt it would give me less control and open me up to new technical limitations. I was inspired by Louise Bourgeois’s use of threads as lines in her work. I use an iPad sketching program to draw simple forms that are easily read with my embroidery digitizing software. I re-draw the images with stitches, lines, and fills, and then embellish the image like crazy. How you program depends on the surface you use for stitching—for example, paper rips easily, so stitch density is a big issue. I think of the textured-motif stitch lines as my drawing line and the threads as my colored pencils. I have been working this way for around eight years, after interning with a commercial embroiderer to learn the parameters of the process.

Caterpiggle (2020), embroidered and sewn encaustic monotypes on encaustiflex (a spun microfiber), 10 by 8 inches

Susan Bennett: The focus of my art making is primarily steel and stainless-steel sculpture. The technical aspects of welding became fluid while perfecting my craft as a pipe welder. Or to put it another way, my welds couldn’t leak under pressure. A few years later, mostly through happenstance, I was pursuing a fine arts degree as a nontraditional student—a woman in her forties. Early in this endeavor, a professor stated that life experience matters in the art-making process, and I would go back to this many, many times. In my studies, I was naturally curious about the history of direct metal sculpture. Now, as it must have been then, the idea of using this ubiquitous material in the creation of 3-D art is liberating. Welding steel, in part, has redefined the elements of modern sculpture. Drawing in space, using this mean material, is free from restraint, and is not unlike the automatic drawing process. Intuitively made, the implementation of the work evolves through an inclusive and integrated design approach. A blend of deliberation and spontaneity that is altogether pleasing.

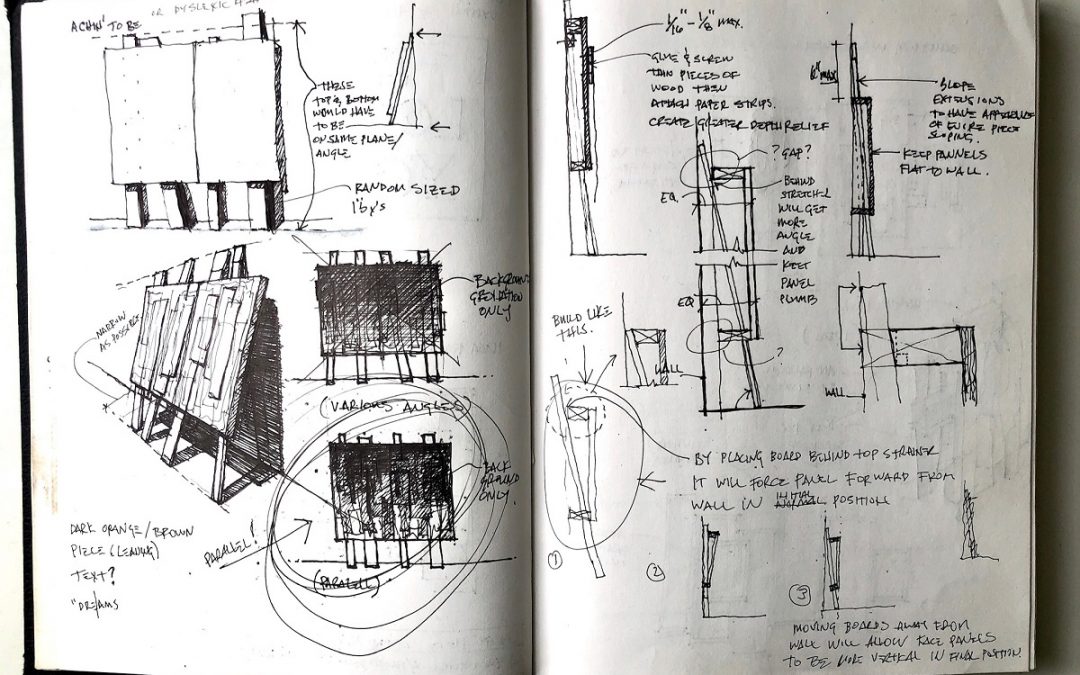

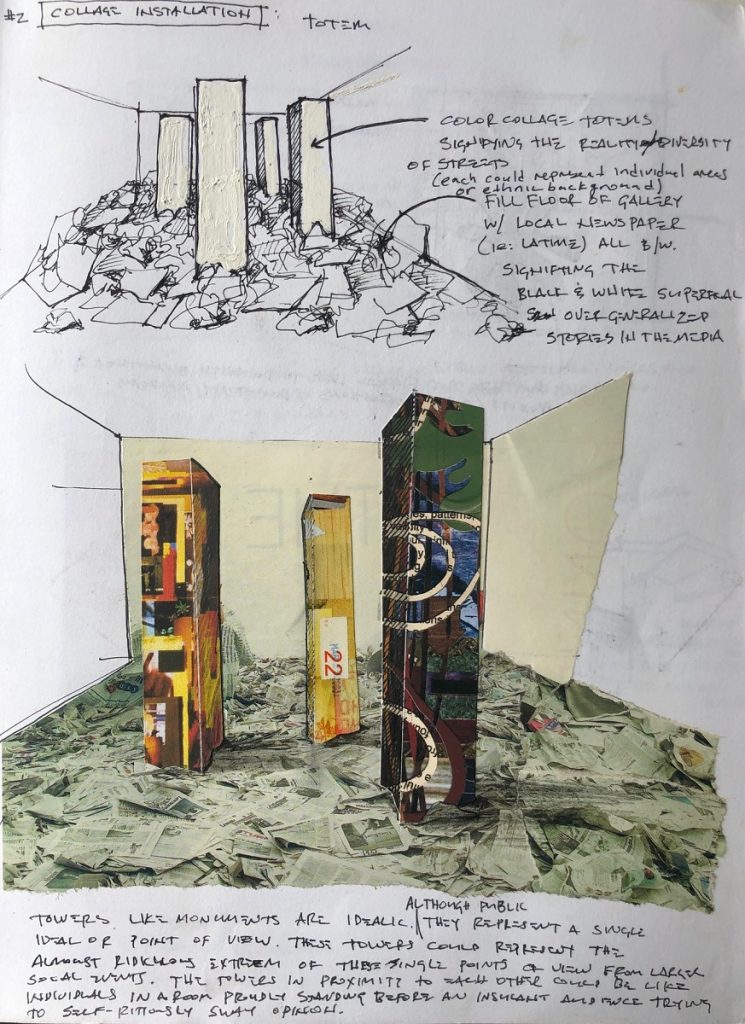

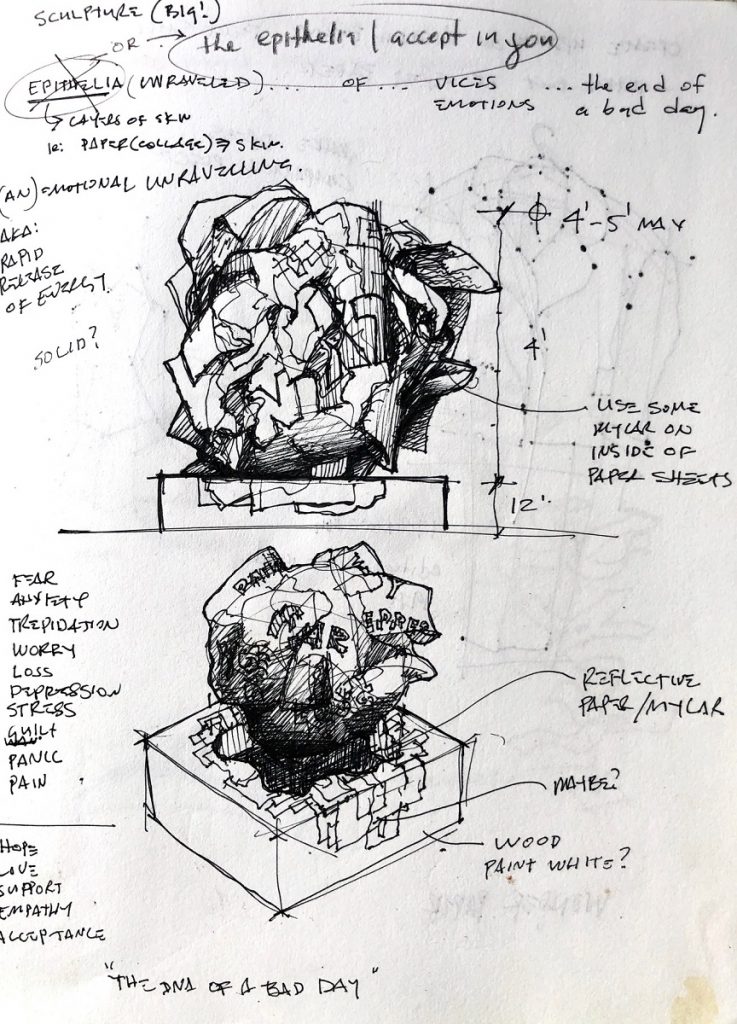

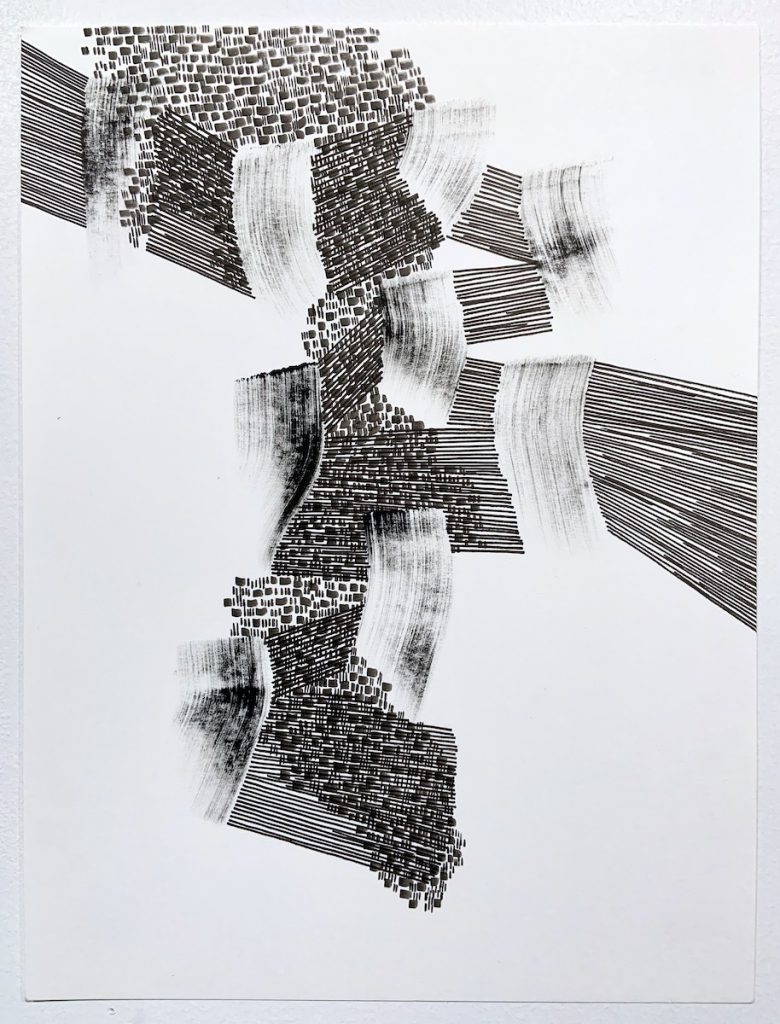

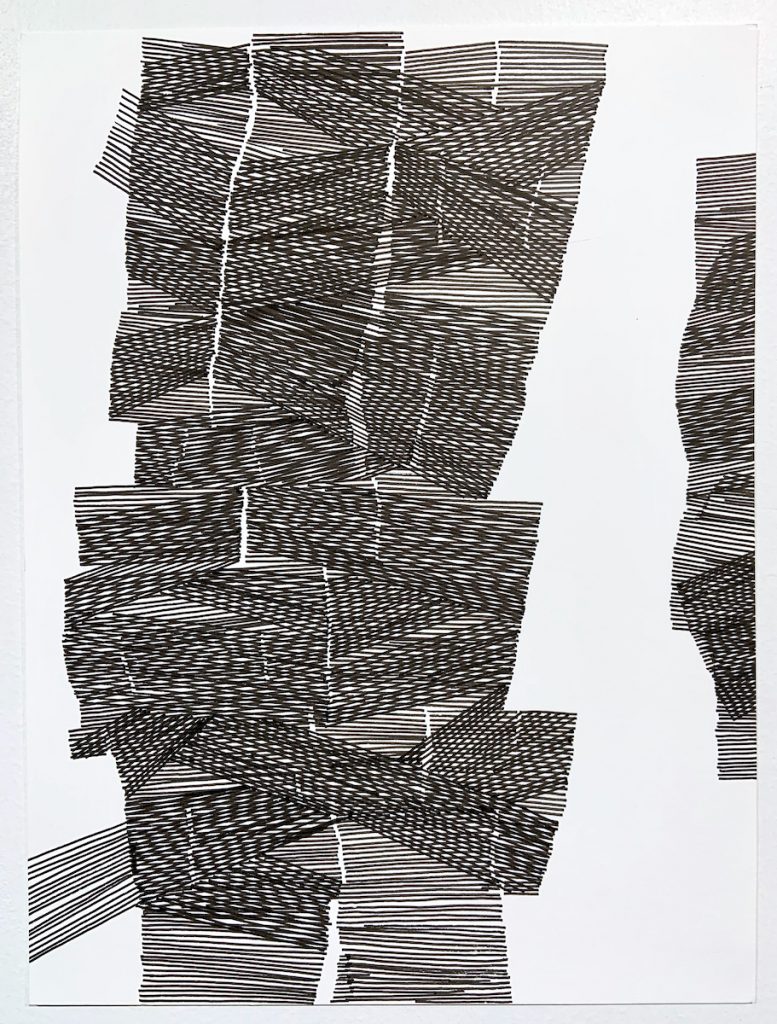

Tm Gratkowski: I was a drawing and painting major as an undergraduate, and later studied architecture in graduate school, so I’ve always been drawing one way or another. For me, drawing is an integral part of thinking, and I’ve always drawn in such a way to communicate ideas. This led to a unique way of mark-making and working through an idea at the same time.

I work only with paper now (collage), so drawing is not a part of my art practice, but my sketchbook continues to be a place where I will test ideas and try to prove or disprove their potential. Currently, because of the self-mandatory isolation we are all going through, I have been thinking about/sketching ideas for future projects until I can get back into the studio, once this is all behind us.

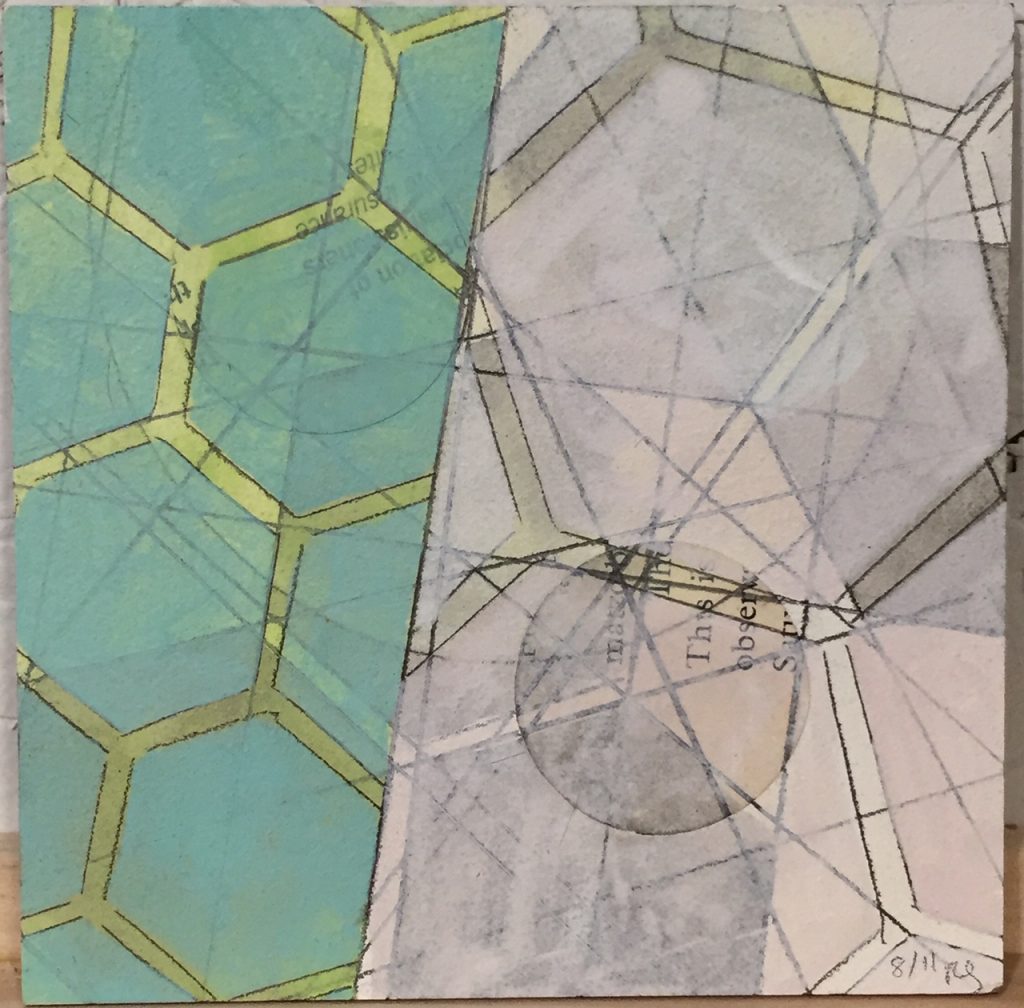

Rita Grendze: I have been cultivating a daily drawing practice for several years—just a few minutes to start each studio session, a habit to help me transition into a working mindset. I draw within simple logistical guidelines, which I decide on the first of each month: size, surface, materials, duration. My goal is to start a drawing every day (with the completion date being loose). I began posting a daily drawing to Instagram last spring, and just reviewed my IG photo portfolio. It’s no surprise that drawings have really changed! While last spring I was joyfully filling the pages of cast-off books with loose, soft geometry in vibrant jewel tones, this fall into spring I have been drawing on stiff watercolor board, with subdued colors and hard-edged forms. A reflection of my current situation? A visual expression of my need for control? Most likely. but I am just going to let these tiny six-by-six-inch visual journals be what they are, judging minimally.

Irene Clark: Drawing is one of the most powerful governing issues in my artworks. My first career as a dancer led me to life drawing. Once I saw the figure in motion again, I became addicted to drawing all the time. I draw for every project and I keep sketchbooks of my series—whether they are animals, botanical subjects, or figures—as well as the wanderings of the stylus of the moment without a goal. I often enter notes and comments. Mystery in my work is a primary issue and nothing about art is more mysterious to me than drawing.

Ellen Weider: My drawings are an important bridge between my prints (basically drawings on copper plates, which are printed as dry points) and paintings. My images float in a mysterious, ambiguous space. Some suggest houses, buildings, rooms, and other architectural structures. There are no inhabitants, but the structures themselves evoke human presence and human interactions. Other works employ organic and geometric forms that create a similar effect. Whether my prints, drawings, and paintings are interpreted as pure abstractions or as self-contained narratives, an ironic humor with a meditative bent informs them.

Claudine Metrick: This piece is part of a body of work that memorializes a dear friend. When Jane first became ill, her father planted sunflowers in a patch of ground near her bedroom window so that she could view them on days she was too unwell to get out of bed. He faithfully tended this space during her illness, and the flower became a symbol of hope for her and her community.

Jane died two weeks before her 41st birthday. At her funeral, packets of sunflower seeds were distributed to her friends and family. At their peak, the flowers I planted were massive – easily eight feet tall with heads over a foot wide. As I sat on the porch taking them in, I knew I had to draw them.

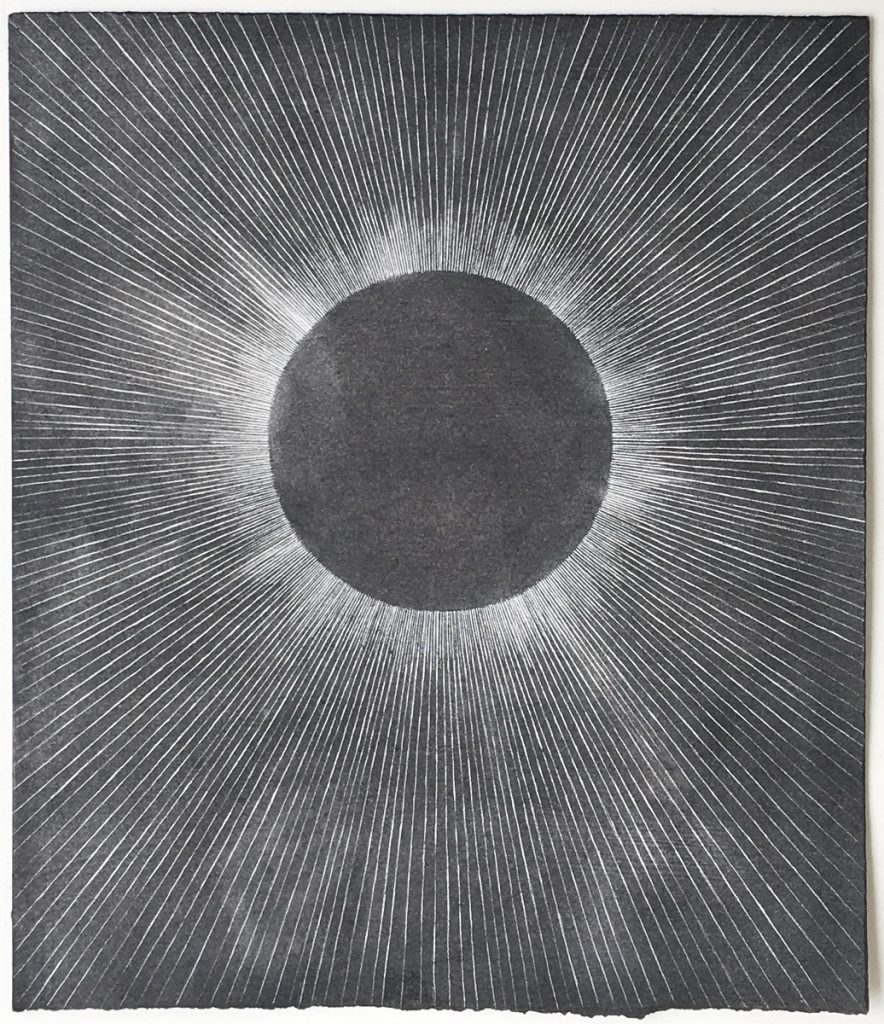

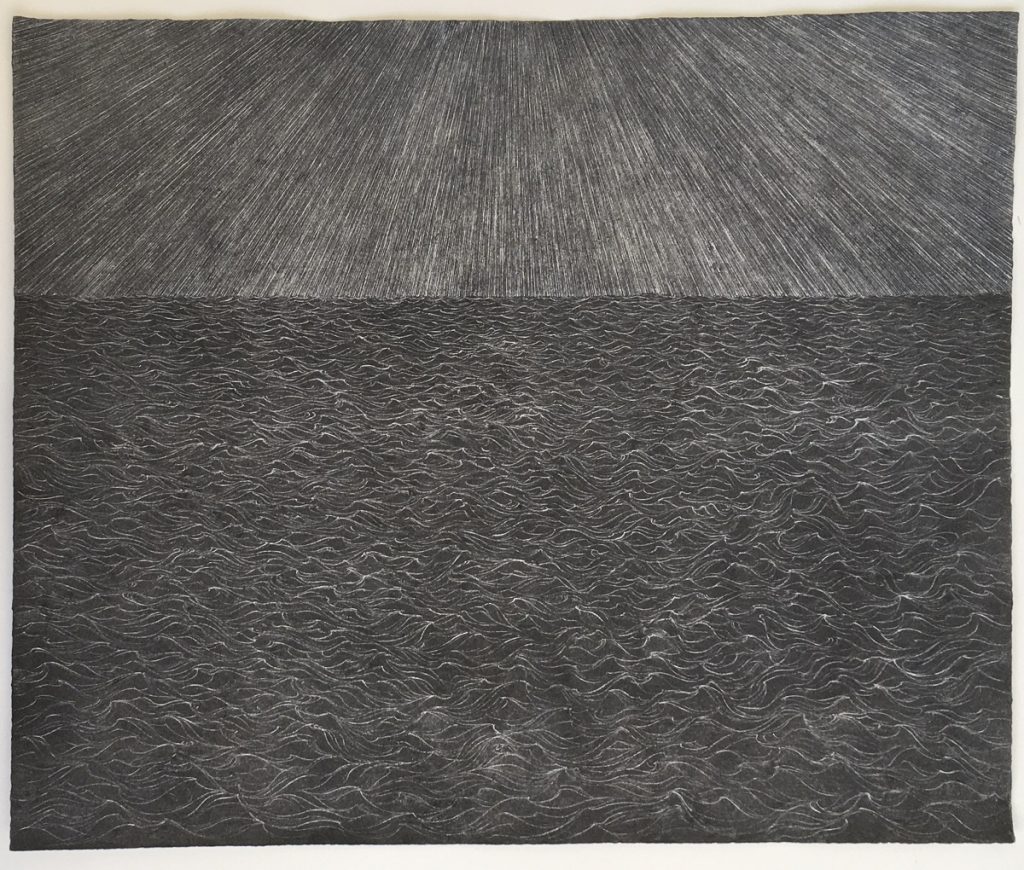

Karen Arm: This group of works on paper is a series of abstract images based on natural phenomenon. I use white acrylic on white paper to draw the image and then I wash over it with charcoal, utilizing a resist-type process where the marks show through. My intent is to have the mark be the source of light in the piece, emerging out of darkness. The work is informed by observed and documented studies of natural phenomenon.

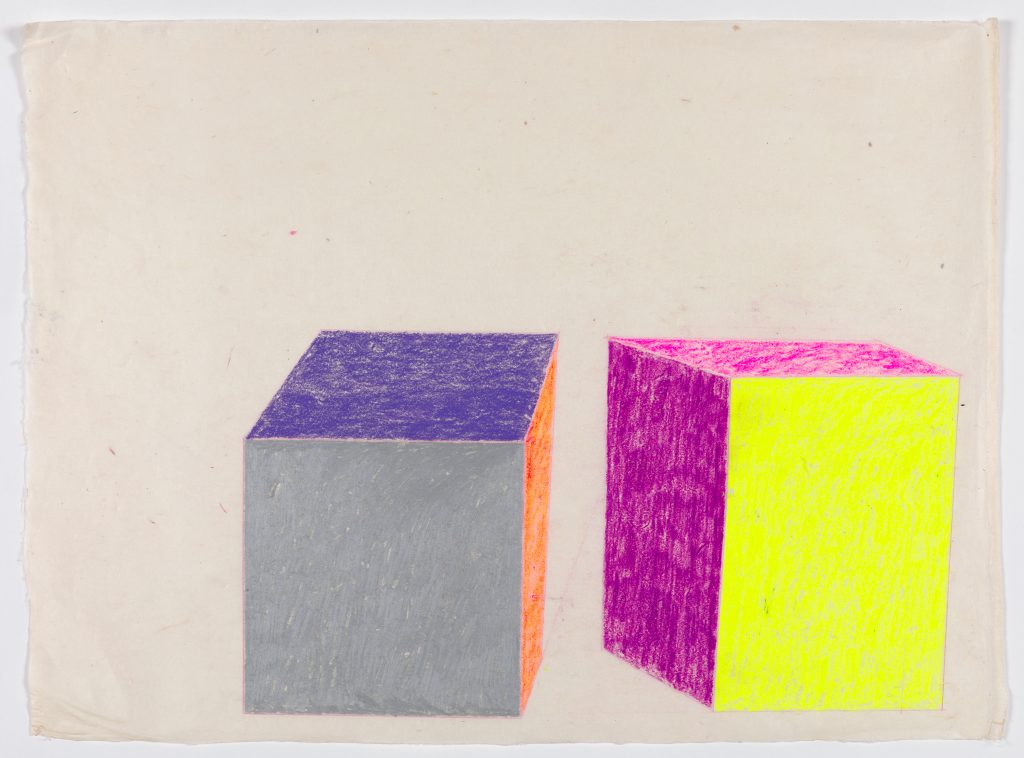

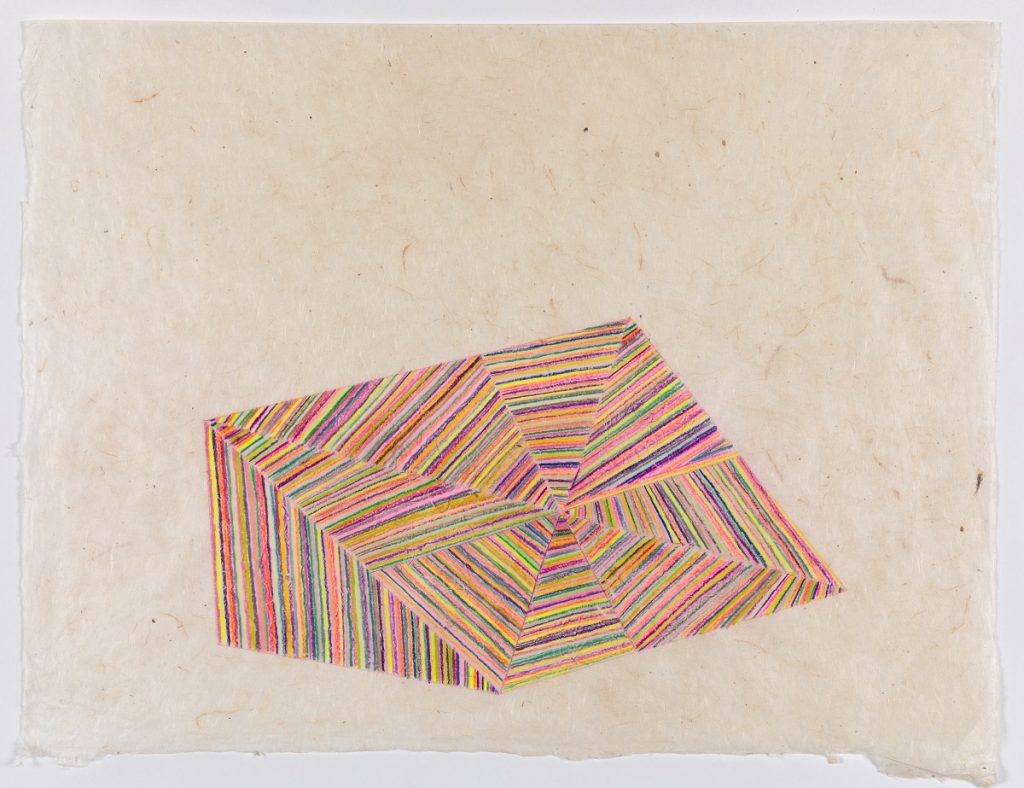

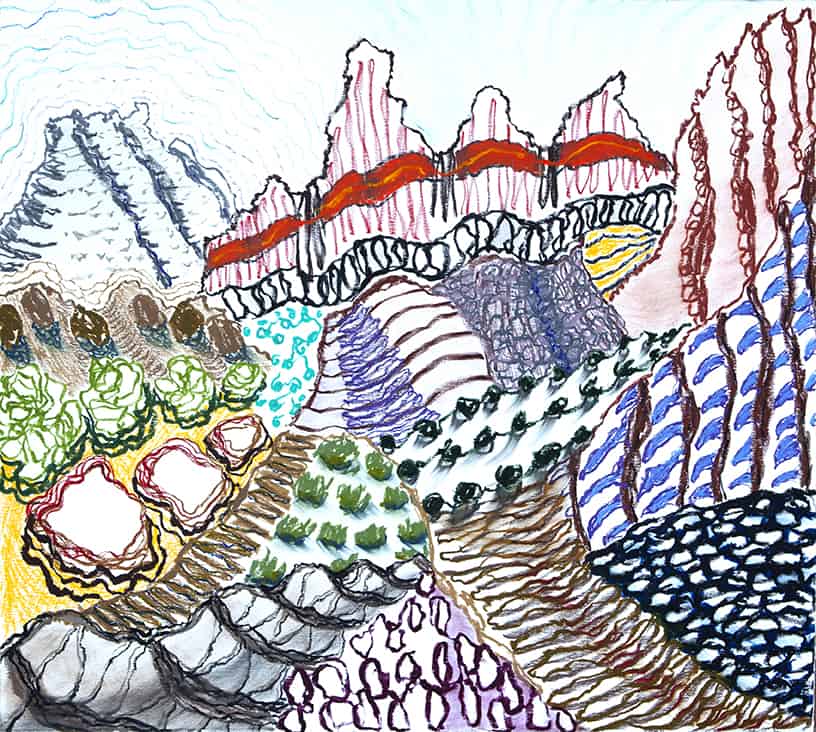

Lily Prince: These oil pastels on 300 lb. paper are from my new “American Beauty” series, made on a road trip to the Western U.S. last summer. They are the largest plein air works I’ve ever done. I usually work a bit smaller when doing plein air work for practical reasons. This road trip took me to Utah, New Mexico, Arizona, California, Oregon, and Washington in my personal search for the beauty still left in our country. I was often drawing either on the side of the road, in 100-degree heat, or in the desert. In these times of environmental and societal devastation it feels urgent to record the beauty that abounds in nature. Especially right now, we desperately need to connect with our environment, as a necessary balm but also as affirmation of our own existence.

Greta Young: Drawing has always played a prominent role in my work, which often incorporates figures. In most of my work I draw from the model and have the benefit of people around me to chat with and compare notes (or that’s how it used to be). Then I work on the last part in my studio. My paintings are a mixture of brush work and drawing, with the drawing being the main influence.

Alyse Rosner: This body of work began as casual automatic drawings in 2018. I bought the paper, thinking I might make something at the kitchen table, on the couch, or on a plane. I never expected to share them and had no idea I would become so connected to these surfaces or that they would become a driving force in my practice.

The drawings are small—12 by 9 inches, black micron pen on hot-press watercolor paper. I draw from varied sources including manuscript Illuminations, Indian miniatures, photos, direct observation, as well as other drawings or paintings I have made. I naturally pursue layers of varied mark making that directly reflect the tools I am using, until a sensation emerges—an atmosphere, a feeling, a presence or a form.

Because we are now quarantined in the age of Covid19, these drawings have become central to my practice. I am drawing while I live, incorporating where I am, what I am thinking, what I remember, or imagine. These pieces are unfiltered, direct output—as honest as I can be—apparitions, veils, obstacles, and simple marks that are blueprints of my stream of consciousness, reflecting the uncharted territory we find ourselves in.

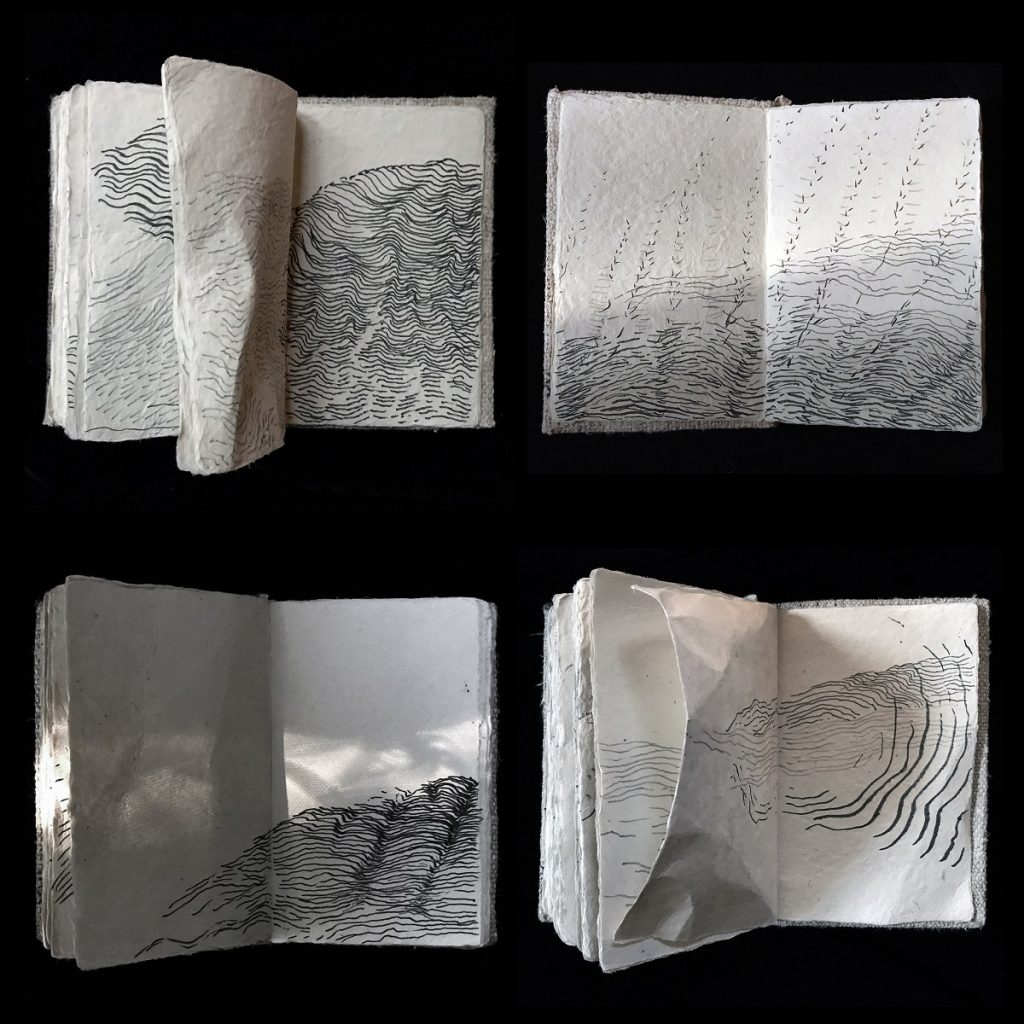

Ann Stoddard: In 2012, I was developing a series of sculptural paintings, which I call Water Maps, when I went through the heartbreak of a divorce. My studio work habits shifted. Feeling a bit lost, I started doing a daily drawing with black-ink brush pens in a small handmade journal. I would sit at a table on my screened-in porch during the early hours of dawn, depending on the weather of that day. I called these drawings Porch Poesy. The series began with the idea of having a daily meditative moment through drawing. These contain references to the weather, the flow of air and wind, the water, the movements of the atmosphere, all embracing the idea of fluidity and moving forward.

Sometimes I manipulate the paper or pages I have drawn on to amplify the idea of movement, very much like my sculptural paintings. I take a photograph of each Porch Poesy using the natural light of the moment. How I use the light in the photograph also becomes an integral part of the new poesy. After I have taken a photograph of the day’s drawing, I post it on Instagram and Facebook. The posts are labeled with hash tags or messages that are positive, and then the post is sent out to the world. The photograph of the daily drawing becomes a new artwork in itself and then further merges into the larger body of photographs of the daily drawings. As of today, I have filled 18 journals.

Porch Poesy Journals from Volumes I-XVIII, 2013,2015-2020, ink on handmade paper, each journal is 5 by 7 inches by 1 inch deep; and open measures 10 by 7 inches

Top: Pages from one of Tm Gratkowski’s sketchbooks

Love the drawing essay series. Thanks for posting!