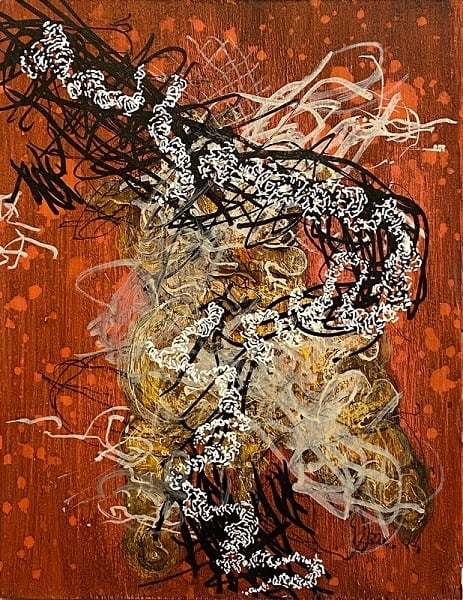

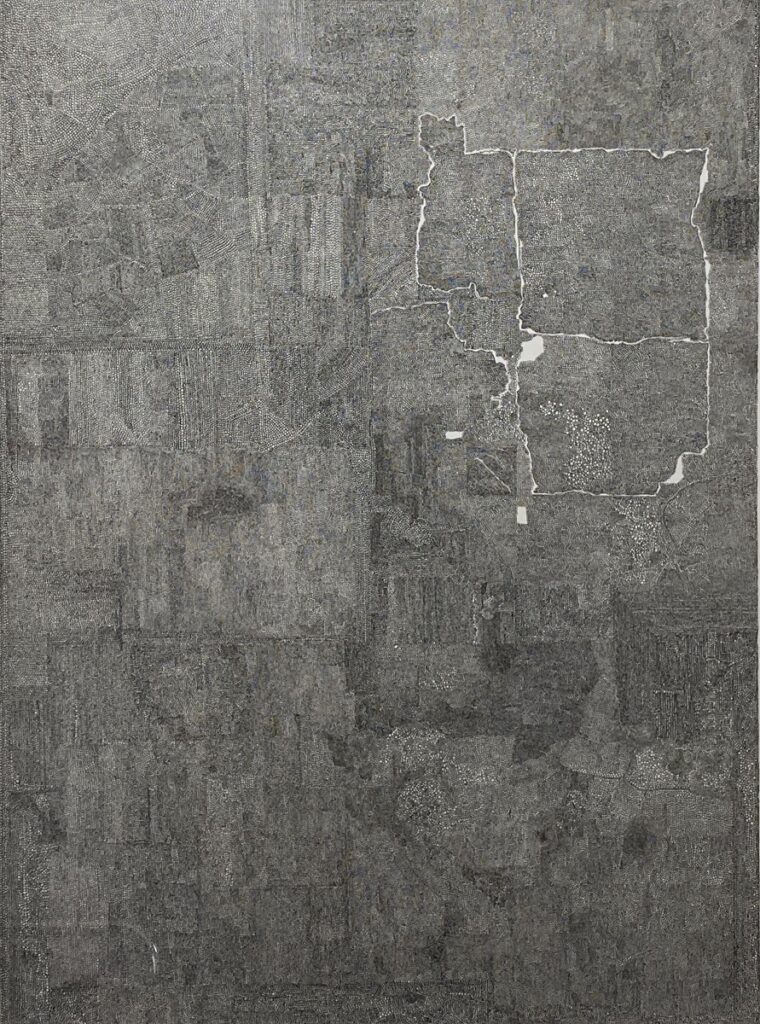

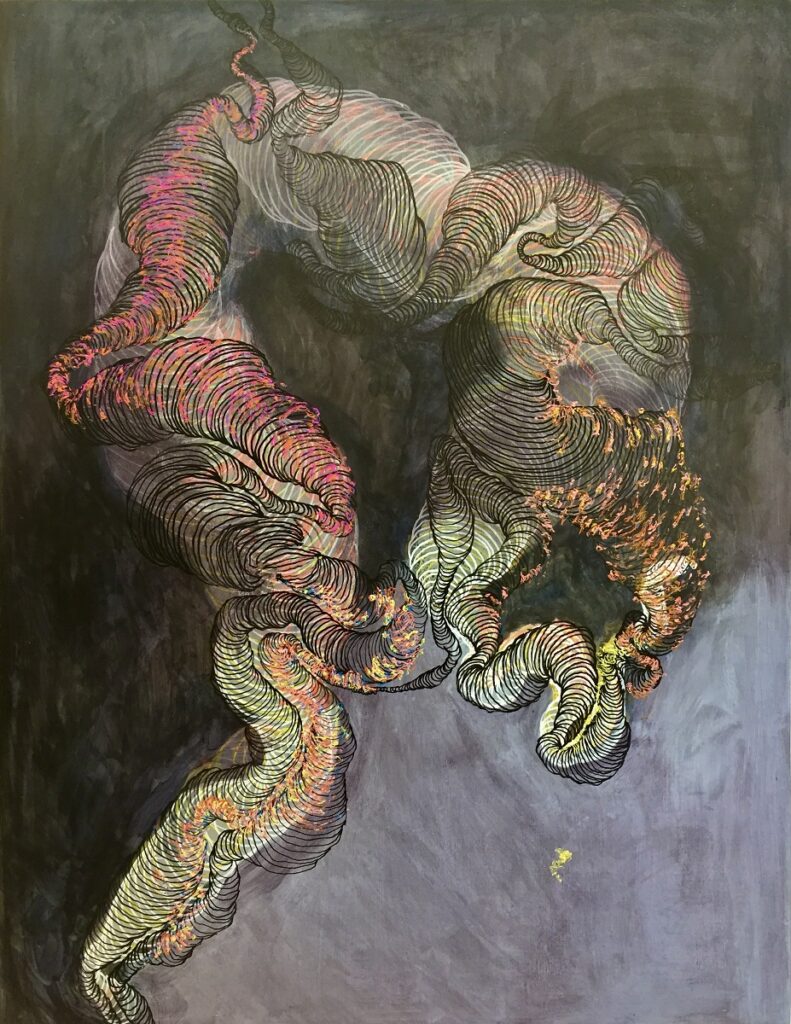

Timothy Nero works in three different mediums—sculpture, painting, and drawing—reflecting a broad spectrum of moods and mental states. In paintings on canvas or panels, lines and ribbon-like tendrils can appear to be spiraling out of control, willfully taking off in different directions like graffiti realized under the influence. Sculptures are awkward shapes bristling with stubby spikes or vaguely anthropomorphic appendages. And drawings composed of thousands of tight circles convey a deeply meditative calm, or perhaps an obsessive need to exert control.

The titles are clues to their origins: Mental Chew Toy, Objects in Consciousness, Shape for Anxiety, Conflicted Thoughts, Mind Lard. Though the average viewer will see these as nonobjective, Nero is adamant in asserting that he is not necessarily an abstract artist. “For years I’ve been interested in the mind, in thinking and consciousness. Thinking is like gears turning, like a watch. And when I talk about consciousness, I’m talking about spirituality as well.” If anything, they are portraits of the way the mind operates, or the way this particular artist’s brain processes experience, whether it’s through meditation or memory.

A certain formal logic holds it all together, as he moves from one workspace to another in his airy two-story studio outside Santa Fe, NM. And though there is little in his background that would presage a career as an artist, he is still moved by the memories of an older sister who died seven years ago. She was born severely mentally handicapped and blind and lived in institutions from the age of ten. “When I did see her, I could intuit sensations of what her life was like,” he says. “I would ask myself, What is the sensation of thought and existence about for her? What is the mind? Mind is nothing but a bundle of thoughts. The drawing 500,000 Thoughts emerged out of all that.”

Nero grew up in suburban Cleveland, “primarily in a flea market,” he notes. His father was a realtor who bought Ohio’s oldest and largest outdoor emporium, where Nero started working on weekends when he was about ten, arriving at 6.30 in the morning and staying till seven at night. “I would pick up acres of trash the day after the market.” Though everything from junk to antiques was for sale, the artist early developed an eye and found a few original Maxfield Parrish prints when he was a teenager. But more importantly, he says, “that flea market experience really informed my sensibilities. I realized that people were not always as they appeared to be.”

His parents also started a high-end furniture store and hoped Nero would get a degree in interior design so he could take over the business. He went to Kent State, where he studied both design and architecture, but in his heart, he always knew he wanted to be an artist. After graduation he went to work at Howard Pimm Interiors in Cleveland. “We’d go to these mansions and help with interior decoration,” he recalls. “I could have cared less about wallpaper and furniture and carpets. What I cared about in going to these very wealthy clients was the art on the walls. I saw paintings by Rothko and original Rauschenbergs and Arakawas. I was holding Picassos in my hands.”

Nero married in 1979 and moved to Tampa, FL, where he made a living hanging wallpaper because “there was no timeclock to punch. I didn’t work for anyone, and I could pick my hours.” Eventually he relocated to Tallahassee and enrolled at Florida State to pursue a master’s degree in art. There he studied with Trevor Bell, the British-born artist renowned for his shaped and exuberant color-field paintings, and “talked his way” into a job as his studio assistant. Bell was not so much a direct influence on the young artist’s work as an example of how a contemporary painter conducts a studio practice. “It was a beautiful template for me.” Nero’s student efforts were a far cry from the elegant, oversized canvases of his teacher. His chaotic, wildly expressionist imagery incorporated howling dogs, aviators on toilet seats, an airplane, and television sets. “The Reagan era and all the saber-rattling threats of nuclear war really colored my subject matter. The work reflected that particular time of madness,” he says.

After getting his degree, he moved back to Cleveland briefly, and then in November of 1991 relocated to Taos, NM. He worked primarily as a sculptor and quickly found representation with the now-defunct Fenix Gallery, attracting collectors from as far away as Los Angeles, New York, Chicago, and Paris, cities in which he also found gallery representation. (As an aside, he adds that he also found a few celebrity collectors.)

The tiny mountain enclave in those days could boast an ambitious museum and significant shows, but he soon realized that “anybody who cared about looking at ambitious art wouldn’t spend a lot of time in Taos.”

After 13 years, Nero moved south to Santa Fe, which offered more opportunities for exhibition, along with proximity to two airports and Amtrak. He has been there ever since, finding inspiration from both within the mind’s labyrinth and, occasionally, from trips to far-flung spots, like Rome, which he visited in 2017. A series called “Mithraium” directly references the warm reds and inky blacks of frescoes from Ostia Antica, an archeological site that was once the harbor city of ancient Rome.

“When I look over the scope of my work from grad school in the ‘80s till now, there’s an interest in extremes,” he says. There’s also a remarkable fluidity among mediums. “I slide back and forth freely between drawings, paintings, and sculpture. It’s not like there’s a specific linear path.” As one reviewer noted, Nero makes work that “moves beyond the frontiers of the space-time-mind continuum. [His] meta-hybrids explore the point at which a painting becomes an object, and vice-versa.” They might also be seen as vivid illustrations of poet Allen Ginsberg’s famous pronouncement: “Mind is shapely. Art is shapely.”

Top: Mithrea Ostia 8 (2019), acrylic on wood, 7.75 by 6 inches

Bravo! Digging in and overcoming all that would hold back your divine expression!

Thanks Cal!

Heal spectacularly as you are spectacular!!!

Great article. So good to see all your good work up on the net. Hope lots of collectors see it!!

Thanks Mary!

I look forward to seeing you and Don in October! I hope that you are both well!

Tim, I love the initial piece on here. Can’t wait to come back so you can share some additional artwork.

Thank you Mary! Come for a visit again!

Your art makes me shiver – deep as it gets

Thanks so much Barb. I appreciate your comments!

What a fine, fine Artist! And a wonderful friend. I have admired his work for years. Love his studio—full of great drawings and paintings, terrific music, and intriguing books. Thank you for this excellent piece, Ann.

Thanks so much for your kind and supportive words Linda!

What WONDERFUL work about a Fantastic Artist!!

Congratulations!! And thank you Nero and Ann!

Great job Timothy, really great read ! Very happy for you.

All my best, Jeff Riley

Thanks so much Greta!

Hey Jeff, Thanks!

I appreciate your comments Greta. Thank you!

Exquisite work!! Great article! Look forward to connecting someday!

Thanks Gregory! Yes we still need to make that happen.

Congratulations-! it’s wonderful to read a little more about you. Not just an Instagram snippet of one’s artistic career. My admiration.

Thanks so much Yenny! I hope all is well with your family and home.