In times like these it’s tempting to fantasize what life might have been like in another century, another culture, among a coterie of friends and acquaintances who had things on their minds other than the pandemic and insane politicians. I’ve occasionally wondered what it must have been like to hang out in the gardens of the Medici with Lorenzo and the young Michelangelo. Or to carouse at the Cedar Tavern with the leading lights of Abstract Expressionism. Or to mingle in a 19th-century salon frequented by George Sand, Chopin, Liszt, Delacroix, and other souls of the Romantic era (try the movie Impromptu if you’d like a cinematic reverie of how these restless and talented folks kept themselves amused).

And so I asked a group of art writers what era would most appeal if they could time travel to another age and place. Of course, as Karen Wilkin reports, it was almost always tough to be a woman. “None of the times that interest me most aesthetically were in any way. welcoming to women,” she notes. “Would you have wanted to be female in Renaissance Venice, even if you got to know Titian, Tintoretto, Veronese, Carpaccio, and Palladio? Late 16th- and early 17th-century Rome wouldn’t have been any better, despite the amazing concentration of great painters, sculptors, and architects there at the time; it was a male, ecclesiastically dominated city, Artemisia Gentileschi notwithstanding. Women didn’t fare well in the 19th or early 20th centuries — pace Berthe Morisot — much as I would have liked to have known Manet or Matisse or Braque. And, of course, I’d want a lifetime supply of painkillers (not opioids), antibiotics, and Tampax.”

Nonetheless our intrepid travelers, male and female, fantasized about evenings with the Dadaists, visits to Rodin’s studio, knocking back tequila with Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo, and sojourns to artists’ workshops in Ghent and Bruges in the age of Memling. Ruefully, though, after her introduction to Johannes Vermeer, Laurie Fendrich’s brave alter ego Lysbeth Jakobzen, confesses: “the visit made me realize it is a bitter thing to be born a woman. I am only 16, and whatever talent I have as a painter will die with me the moment I am married.”

But it’s always fun to dream.

From upper left, clockwise: Fernand Fonssagrives, Lisa Fonssagrives-Penn (then Lisa Fonssagrives), Leslie Gill, Frances McLaughlin-Gill, Kathryn Abbe. Photo by James Abbe, Jr., c. 1947

Carol Kino: I would choose to live in the period of the book I’m writing for Scribner, provisionally titled The Fair-Haired Girls: The Twin Photographers Who Helped Define the Fashion Magazines of 1940s New York. The twins were at art school in the late 1930s, when New York City (and America) was emerging from the Depression, and they began their careers in the 1940s, during World War II, when young women suddenly got access to creative jobs that had previously gone to men. During this period many young women became magazine photographers. My twins were Kathryn Abbe, who free-lanced for all the new career-girl publications that flourished during the war, like Mademoiselle, “for Smart Young Women” and Charm, “for the Business Girl”; and Frances McLaughlin-Gill, the only woman to join the Condé Nast Studio, working primarily for Vogue and Glamour, “for the girl with a job.” Both twins loved working outdoors and on the street, and much of their work looks current today.

Frances McLaughlin Gill, Reginald Marsh, Alfredo Valente, under the Brooklyn Bridge while filming the MGM short “Art Discovers America.” Photo by Kathryn Abbe, 1940

Creatively I think of this period at Pre-Mo (as opposed to Po-Mo). The city was barreling out of the Depression, everyone was glad to find work, everything was new, and anything went. The twins studied art at Pratt when the school had just started the country’s first major course in Industrial Design, which here began as a profession built by creative people–artists, theater designers, graphic designers, jewelry designers, etc.–who needed to make trains, planes, automobiles, toasters and cameras sexy enough that people were desperate to buy them when nobody had much money. New York was filling up with refugees, Surrealists and Bauhauslers among them. Dali shocked and thrilled the public with his crazy store windows and his Dream of Venus girlie pavilion at the World’s Fair. Moholy-Nagy came from Chicago to Pratt to give a lecture, which was much anticipated but also panned for its dryness. A dealer like Julien Levy wasn’t only showing “high” artists, like Picasso; he was also showing Disney watercolors and the “surrealistic” paintings of the comedienne Gracie Allen, whose benefit for Chinese war relief drew lines around the block. American art was coming into its own, courtesy of the new Whitney. The new MoMA was putting on huge surveys of “modern” things–folk art, Bauhaus, Surrealism, photography–in a variety of odd spaces, including the brand-new Rockefeller Center. Even newer: photo magazines, like Life, Look, Coronet, U.S. Camera and Popular Photography, and massive photo surveys, which displayed all sorts of pictures together–photojournalism, fashion, theatrical, food and dance, photos of kids, families, ships, and the great American landscape. Shows like this drew huge crowds wherever they toured, sort of the analog precursor of Instagram.

This was also a period when, if you were a girl who lived in the Midwest in a small or medium-sized town and you didn’t fit in, you came to New York City to solve that problem. (Probably a guy, too, but I’m looking at the female perspective.) Conversely, if you were a European Jew or a dissident, you came here to stay alive and you often ended up in New York. It was these two forces combusting that must have made the city so thrilling. And a lot of that talent flared up in magazines, the place where writers, photographers and artists could make money. Even though paper and film were scarce, they grew increasingly experimental during the war, and in the early 1940s, as young men went off to war, a lot of the people making them creative were young women, freed to do as they wanted with little oversight until the men came home, the bell jar came down, and women had to wait until the 1970s to even think about being taken seriously, let alone imagine being rediscovered.

So to have been really young during that first burst of un-self-conscious freedom–that would have been the period for me.

Franklin Einspruch: Hakuin Ekaku gave up on the brush in his twenties to fully devote himself to Zen, of which he became one of the giants. But he took up painting again in the three decades leading up to his death in 1769 and produced renowned works. If fate timed it right, a monk training under the elder Hakuin could have come into contact with students who likewise achieved great artistic and spiritual accomplishment: the explosive Tōrei Enji, the laconic Reigen Eto, and the gentle Suiō Genro, who was a confrere of the mighty Nanga painter Ike no Taiga. One thus could have been a part of, or at least witness to, a time of fresh vitality in Rinzai Zen and a massive expansion of pictorial and technical possibilities in late Edo art. Here is a picture of me getting knocked on the head by Tōrei.

painting again in the three decades leading up to his death in 1769 and produced renowned works. If fate timed it right, a monk training under the elder Hakuin could have come into contact with students who likewise achieved great artistic and spiritual accomplishment: the explosive Tōrei Enji, the laconic Reigen Eto, and the gentle Suiō Genro, who was a confrere of the mighty Nanga painter Ike no Taiga. One thus could have been a part of, or at least witness to, a time of fresh vitality in Rinzai Zen and a massive expansion of pictorial and technical possibilities in late Edo art. Here is a picture of me getting knocked on the head by Tōrei.

.

Kim Levin: My grandmother used to marvel that she was born in a time before electricity, before the car, before the telephone, and that she lived to see men walk on the moon. As someone trained in archaeology, I wish I could say I am content to be living here and now, despite the ongoing hardships of a horrible pandemic and the political disasters of the past four years. What could be more horrific and more thrilling than actually experiencing firsthand the near-collapse of one’s own nation, one’s way of life, and one’s art world, accelerated by the attempts of “the most dangerous man in the world” to destroy the system. But I am far from content. Our ever less-habitable planet and the mass extinction of life, including perhaps our own species, is nothing to wish for. Nor is the destruction of civilizations.

I would settle for living in a postmodern and pre-digital time, when everything was easier. Post-minimal and conceptual New York in the 1970s would probably do fine. From the 1970s and early 80s, years when New York City almost went bankrupt, Modernism seemed obsolete, AIDs hadn’t yet attacked the East Village art community, digitalization hadn’t yet infested our brains, and the Worldwide Web was a distant dream. And everything seemed possible as artists attempted to start over from scratch.

Or if I were to choose a really artsy place to teleport myself to, I might pick Amarna, the new city the Pharaoh Akhenaten built in the 14th century BCE. He turned Egyptian traditions, art, and religious beliefs inside out, presiding over a revolution of sinuous art nouveau-like images.

Edith Newhall: I’d like to drop in on Mexico City in the early 1950s. There was such an interesting, diverse community of artists and writers living there at that time: the painter and writer Dr. Atl (Gerardo Murillo Cornado); the ex-pat Surrealist painters Wolfgang Paalen, Remedios Varo, and Leonora Carrington; and the British ex-pat

collector of Surrealist art, Edward James, who lived in Xilitla and frequented Mexico City. Add to that mix the novelist and diplomat Carlos Fuentes; the film director and screenwriter-turned-painter Gunther Gerzso; the architect Luis Barragan; the poet Octavio Paz; the photographer Lola Alvarez Bravo, and of course Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera. A heady, politically active group, and lots of brilliant minds and eccentrics. P.S. Mexican cuisine and the way it was prepared at that time would draw me there, too.

Peter Plagens: There’s a paradox here. Going back in time and in space is one thing if it’s sort of A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court deal, and I see what’s what through 21st-century eyes. It’s another if I’m a person of the time and place, e.g., if I’m a cave dweller around Lascaux in 20,000 BCE, I’ve no idea that the drawings on the cave walls are so wonderful. Also, I’d love to zip through one of those time/space wormholes and be among some exotic Asian or African art I’ve never seen, but I don’t know enough to concoct a fictive identity that’d give me access to what I want. Anyway, playing along….

I’d like to have been an enlightened, albeit nominally practicing Catholic (no heretics’ torture for me!) merchant in 15th-century Flanders, able to see early Flemish painting hot off the easel. (That last makes a difference. I went to St. Petersburg in the ‘90s to see a bunch of early Modernist paintings that had been kept in a dark room, a de facto vault, in The Hermitage, for decades—to keep them from both the Soviets and the Nazis. They looked like the oil paint was still wet. Exhilarating!)

I’ve commissioned Hans Memling to do a painting for a local church, a portrait of a saint, probably, since a triptych is a little high-end for my means. As a side commission, Memling does a portrait of me—the mid-range model. (A plain wall background was the cheapest, a wall with a window through which a landscape fragment was visible was next up, and a full landscape background cost the most.) In my professional travels, I get to go to Ghent and Bruges and insinuate myself into various artists’ workshops. Even though I’m of that time and place, I kind of know the local, contemporaneous painting is superb. I’ve even have heard tell that the Italians, when they saw part of Hugo van der Goes’s Portinari Altarpiece, realized they knew comparative diddly about oil paint, and were really envious. Nothing like making those decadent southerners gnash their teeth.

Elisa Turner: As the devastating plague year of 2020 grinds to an end, numbers of the daily death toll splash across banner headlines of the digital Miami Herald. They are like gruesome stains in one crime scene after another. Still, the desperately needed vaccine is no longer a promise, and the prospect of traveling and gathering in groups no longer seems like an impossibly distant dream. Blessed to be safe and socially distanced in Miami, I am longing to see art without needing to wear a mask. Right now I can’t think of a more delightful time and place to visit via teleport (nodding to that famous pre-presidential election Saturday Night Live skit) than a few years in Paris during the era known as the “Banquet Years.” Those years are indelibly described in Roger Shattuck’s classic book of the same title about the Parisian avant-garde from 1885 to World War I.

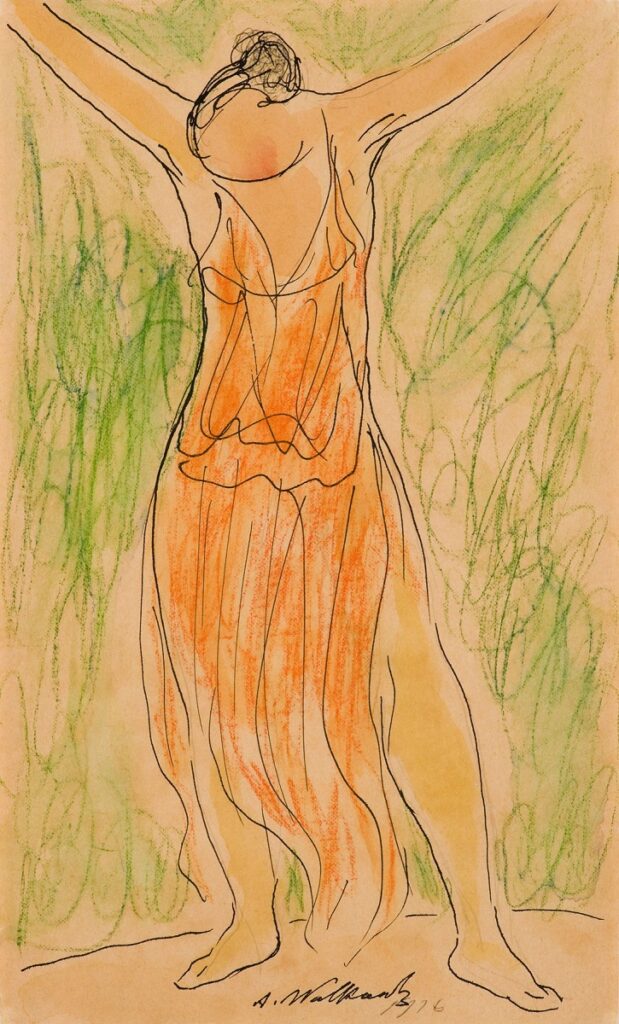

It was a time with much creative crossover in the arts. American artist Abraham Walkowitz found his way to Paris and the studio of Auguste Rodin, where he had the excellent fortune to meet legendary dancer Isadora Duncan. Not only entranced by Modernism blossoming throughout Europe, Walkowitz was captivated like Rodin and countless others by Duncan’s fluid, free-spirited movement. What a thrill it would have been to walk under the graceful, sinuous structure of Hector Guimard’s arching Art Nouveau entrance to a Paris Metro station and travel to a station near Rodin’s studio. At the studio I might have had the chance to chat with both artists and see first-hand how Duncan’s own sinuous grace fired their imagination. Possibly I could have even met Loie Fuller, another legendary dancer known for inspiring Rodin as well as Toulouse Lautrec and the poet William Butler Yeats.

Exploring the streets of Paris, I would love to walk among neighborhoods that photographer Eugene Atget was in the process of capturing, recording them with his exquisite sense of rhythmic architectural detail, his empathetic sense for a pace of life on the verge of dramatic change. What a gift of chance it would be to encounter him with his camera, to ask him why he chose to take a particular shot. Then there’d be the breathless allure of navigating hilly, cobbled streets of Montmartre, clustered with cabarets and studios for Picasso, Modigliani, and others. For one magical evening in a cabaret, I would savor glasses of absinthe and quite literally rub shoulders with artists. There would be dancing long into the night, swaying to the delectable music of piano player and composer Erik Satie. Thanks to my fantasy sojourn via teleport, I would relish every minute of Montmartre’s seductive, absolutely quarantine-free night life.

Peter Frank: I would like to have run with the Dada (and Dada-adjacent) crowd, from Paris before World War I to Zúrich during the war to Berlin and back to Paris—and Köln and Hannover and Brussels and Holland and Prague and wherever good Dada sprang up. The Cabaret Voltaire sounds like a fun boîte, the German Dada shows were punk avant la lettre (and it would have been nice to see all those rickety collages before the newsprint started to yellow). And imagine hanging with the likes of Schwitters and van Doesburg as they tickled the Dutch, challenged the Bauhaus, and… well, provoking the Nazis came a little bit later, and I don’t think I’d be comfortable in the same room with those folks. So let’s make the time frame 1912-1928, the geographic span from London to Leningrad, and the cast of characters large and varied. It could but wouldn’t have to include New York. I know the Dada (proto-) movement there was lively enough, but I’ve already lived through one or two great scenes in my hometown. Indeed, navigating the Big Apple in the 1960s and ‘70s was like navigating Europe in the teens and ‘20s, only back then the continent was one big New York, and in my salad days, New York was one small continent. In both cases, though, you had a real art world, and an endlessly fascinating cast of characters.

The following letter, dated 1673, was found in early 2020 by construction workers renovating an old house in Trier. This letter is translated from the Dutch by Laurie Fendrich, whose Dutch is admittedly a tad flawed.

1673, December 3

Dear Anneke,

Your letter was delivered yesterday. Alas, it took six weeks to arrive. Trier might as well be the other side of the world. I have come upstairs to the back room in order to write you without being disturbed by my brothers and sisters.

Yes, since you asked, I still have my easel in my dear Father’s studio, but I don’t think this will last. My dear Mother says a woman who paints pictures will never find a husband. Father is less harsh, but though he tells me I’m talented, and a good assistant to him, no honest woman paints and sells pictures. Despite a decline in the number of clients, my dear Father continues to make profits from the sale of his (and others’) still life paintings on the street. Between you and me they all look alike, but who am I to question taste in flower paintings? May the Lord continue to Bless my dear Father, at least until he can purchase a complete bed and several more hogsheads of wine.

Three weeks ago, seeing how very sad I looked, my dear Father let me delay grinding his pigments to visit my friend Maria Leeuwenhoek, who lives across the city from us. Maria’s Father, Antonie Leeuwenhoek, deals in tapestries. Did I tell you about the time we were eight and he showed us how a shimmering glass pearl measures the depth of cloth weavings? I wanted to hold it, but he wouldn’t permit it.

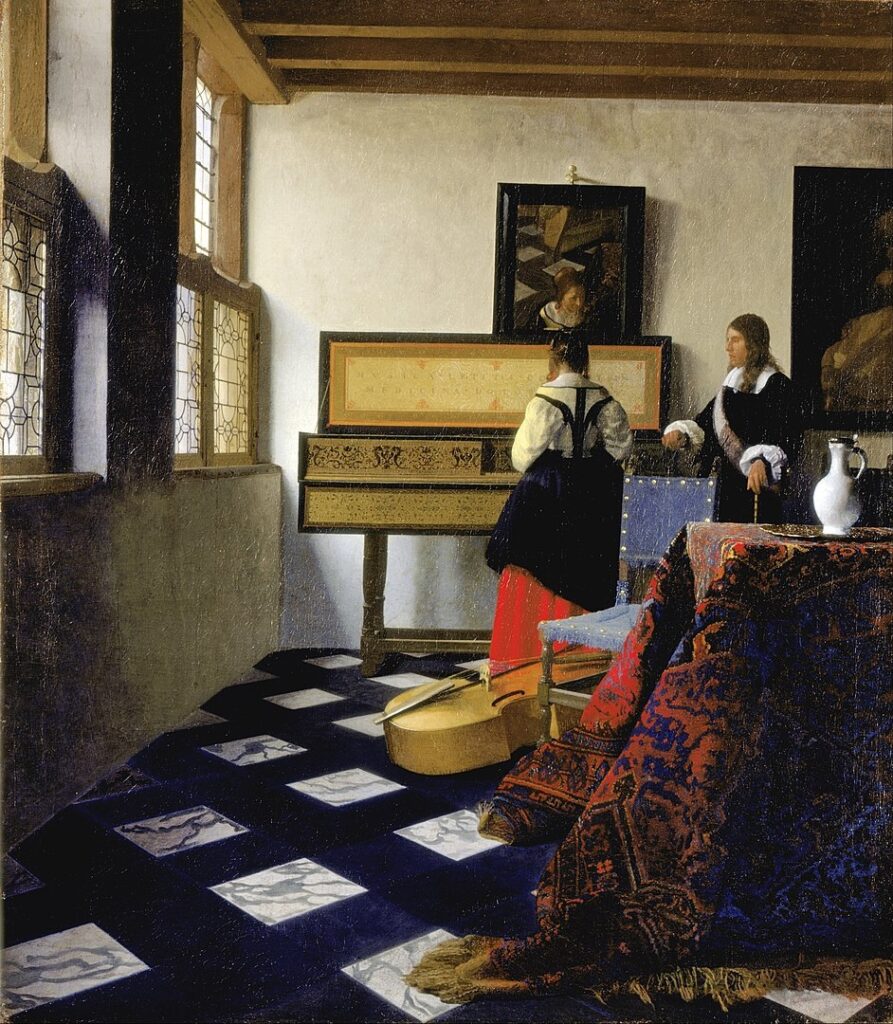

In any event, on this most recent visit M. Leeuwenhoek asked Maria to take a small package to Johannes Vermeer, another painter here in Delft who has quite the local reputation. Because they are both members of the St. Luke’s Guild, my dear Father and Johannes Vermeer are friends as well. My dear Father tells me Johannes Vermeer knows a lot of fancy tricks and is an excellent craftsman of light, and since I would love to learn how to paint better than my dear Father, I was eager to meet him.

We stood several minutes in the foyer after the maid let us in, watching children of all ages, half-dressed and rather unkempt, laugh and scream as they chased one another. Maria grew impatient and suggested we go upstairs to the studio. No one was there, and everything was as calm and quiet as the surface waters of the canal on a hot August day. I noticed a large jar of lapis lazuli next to his mixing table. Father has said Johannes Vermeer has only one patron, so I do not know how he affords this.

Suddenly, the artist himself emerged through a small door in a corner closet. He seemed extremely agitated to find us in his studio. When I asked him what was inside the little room, he was most secretive. It must be very important to him.

Anyway, the visit made me realize it is a bitter thing to be born a woman. I am only 16, and whatever talent I have as a painter will die with me the moment I am married. Yet marry I must, as my dear Mother reminds me, for we are not so rich that I can remain in the household after I turn 20.

Anneke, for all the stress the painters of Delft are going through after the rampjaar, when so many of them lost their patrons, truly I believe a painting talent is a blessing from our Dear Lord.

My love to your Father, who to this day is my only client.

Love in Christ,

Lysbeth Jacobzen

Top: Norman Bluhm, Joan Mitchell, and Franz Kline at the Cedar Tavern, 1957

Interesting question and, as Karen Wilkin noted, most times, perhaps all, were tough for women. Still are.