More about relationships between dealers and artists

As we pointed out a couple of weeks ago, the connection between an artist and her dealer is often as fraught with difficulties and potential for misunderstandings as even the best of marriages. And as methods and means of promoting work evolve over time—primarily because of social media, art fairs, and the problems of the traditional bricks-and-mortar gallery–the nature of the game is rapidly changing.

Dealers, Collectors, and Curators

The gallery is your conduit to the big leagues, making connections with museums and collectors whose names add cachet to your reputation. “Oftentimes a collector will have a strong affiliation with a specific institution,” says Charlotte Jackson of the gallery by the same name in Santa Fe, NM. “In that case they can make recommendations, saying that so-and-so’s work might fit in well with a show or with the collection in general.” And that kind of matchmaking can offer the greatest of satisfactions for both dealer and artist: It’s hugely gratifying, notes Mary Sabatino, vice-president and partner at Galerie Lelong in New York, “to go into a museum and see work that you’ve placed there, to go into collections, to know that people are enjoying the work, and in some cases their lives may be changed by it.”

But many artists have been caught in the situation where the gallery expects them to bring in the clientele. “I once had a dealer hang a solo show of my work in his gallery in Newbury Street in Boston, back when it was the street for fine-art galleries,” recalls Peter Roux. “Then he told me I needed to inform collectors about the gallery, the show, and to convince them to attend the opening. When I told him I would be happy to supply him with my collector list so that he could promote to them, he indicated to me that this was to be my job, not his. He had already supplied the space and the gallery name, and that was big. He expected me to do the lion’s share of promoting.”

How you feel about such an arrangement will depend on many variables: whether you do indeed have a substantial list of collectors (or even just a few), the prestige of the gallery in question, where you are in your career, and what kind of financial arrangement you have with a dealer. If you’re new to the game, you probably need a more nurturing sort of environment, a dealer who wants to take you on and really “grow” your career. If you’re a seasoned pro and have a number of avid followers a dealer would like to bring into her fold, then you might think about negotiating a better cut in sales (see below, The 50-50 Split.)

As sculptor Ted Larsen points out, probably “95 percent of art venues are ‘fishing galleries’—they wait for the clientele to come to them. And “there has been a significant shift in the collector base,” he adds. ”It has narrowed in volume as the upper-middle class is pinched more and more. On the other hand, the wealthy class has more money than ever and continues to drive the market. But they don’t ‘shop’ for art. They have advisers and are used to art coming to them instead of going out to find it. That all shapes up to big structural challenges to the old gallery model, where patrons came to them, regardless of their financial position.”

Larsen thinks galleries could be doing more—private parties held at the gallery, studio tours conducted by knowledgeable curators or advisers. “Dealers must be pro-active and reach out to these collectors with special events made just for them,” he believes. “Gallery openings just aren’t enough.”

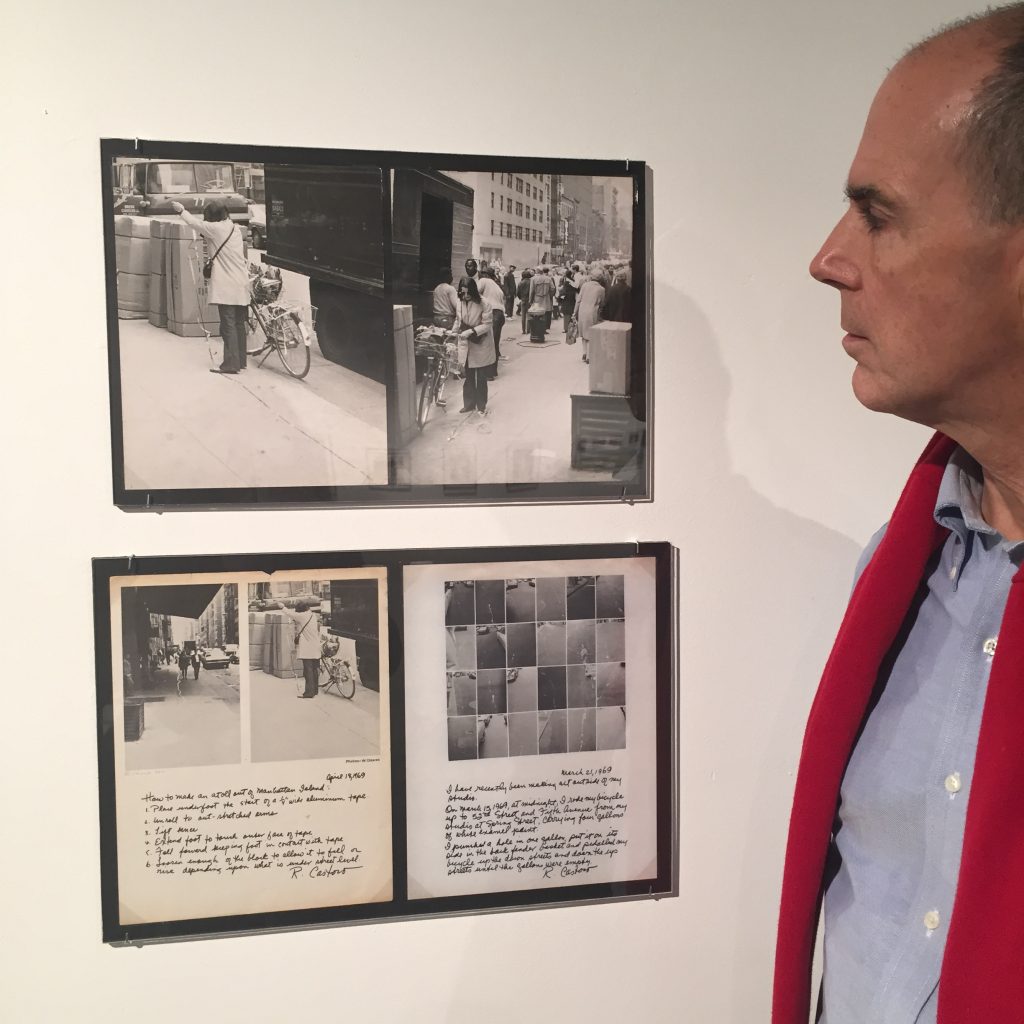

Dealers’ relationships with curators may not be quite so collegial as they were in the past, when a curator from the Museum of Modern Art, say, could easily nip over to Sidney Janis or Leo Castelli to see what was in the air. “Today a lot of curators don’t want to be told what they should look at,” says dealer Hal Bromm, who has been in the business in Tribeca for more than 40 years. “For the most part they want to decide what they like. And they’re under stress because suddenly everyone’s a curator.”

Says Kathryn Markel, another dealer in New York, “I don’t think I’m a typical gallerist. Unlike most of my comrades, I spend much more time concentrating on building up an artist’s sales market than in building up their careers via curators and museums. I promote their work heavily to clients—these days via social media, which includes Facebook, my picture of the week, and a clear website presence.”

And yet, points out Eric Brown, owner and director ofTibor de Nagy Gallery in New York, museums rely on galleries to be invaluable resources when an exhibition or publication is in the works. “The gallery’s extensive archive can provide pertinent information about collections, biographical information, high-quality image files, and an intimate knowledge about an artist’s work, particularly those we’ve worked with for years and decades. We are not just promoting the work, we are promoting a narrative.”

The 50-50 Split

In bygone days, when dealers acted more like patrons and brokers than stores, half-and-half (or perhaps more for the artist when materials are expensive, as for bronze or high-tech gadgetry) seemed an equitable arrangement. But some question the fairness of this agreement when so many artists may be doing the lion’s share of promotion, especially though social media. “Galleries need to prove why they are worth a 50 percent commission, now more than ever,” says Roux. “The better dealers can make a case for it, the worst can’t.”

Sometimes the split may not even turn out to be 50-50. “I’ve had dealers ask me what I want for the work when it sells instead of what I want the retail price to be,” says Roux. “Going this route means the dealer can feel obligated only to give the artist what he has said he wants when the piece sells. That potentially allows the dealer to make more on the sale. I’ve lost count of how many artists—especially fresh out of school and unknown and unrepresented—have talked about how willing they are to agree to just about anything in order to get a gallery even to consider taking on some of their work. But I’ve never once heard a gallerist complain that there were not enough artists for them to choose from to fill their spaces.”

But a trend toward greater self-sufficiency, abetted by the Internet, seems to be rapidly changing the nature of almost every aspect of the gallery-artist relationship. “Artists can get stuck because they’re waiting for a gallery to take them on and make their careers,” says Danae Falliers, a photographer who divides her time between Colorado and New Mexico. “If they can run their studios like a business, they can get their work out to a much larger audience and diversify opportunities and sales.”

The Long (or Short) Good-Bye

Dealers and artists part ways for any number of reasons, but one of the most common cited by galleries is when an artist starts selling aggressively out of her studio, without granting the original agent any commission. That can be particularly galling when a dealer has devoted a fair amount of time in promoting an artist and showing her work. Equally infuriating is “when those artists you’ve nurtured go to another gallery, and the new venue picks up the dividends you’ve invested,” says Bromm. In that situation, he may typically ask, “’What are you going to do for me?’ I’ve reserved the right to buy certain works so that I can realize something from my investment of time and energy.”

But sometimes both dealer and artist need to move on. If an artist shows with another gallery, even with the original dealer’s approval, and Gallery B can command higher prices than Gallery A, then the relationship may be over. “An artist might also feel his work doesn’t fit into my program anymore, or it’s not a good context for his objectives,” says James Kelly, who recently closed his gallery in Santa Fe to work for Gagosian in Los Angeles. “Or artists don’t think I’ve been selling enough for them, or I haven’t been able to find the good collectors. Sometimes I can’t keep promoting the same artist to the same people. The collector base is limited after working with an artist for several years.”

In an era when there seems to be counseling for almost any difficult situation—from the loss of a pet to the meltdown of a marriage—it seems odd that no mental-health professional has jumped into the vacuum to resolve tensions between dealers and artists. Nor are there unions for fine artists to represent their interests across the board. Peter Roux notes that artists are even reluctant to share their problems with one another so that they might identify some of the issues to look out for. “We’re wary of complaining about unscrupulous practices, particularly on any social-media platform, for fear of being blacklisted,” he says. “We all need to help one another as we are a large group of isolated folks who work with no group protection. Identifying issues with gallerists, especially if they are chronic, can help someone avoid that issue with that party in the future. And we can help by putting out ideas for resolution.”

But how to organize a group of people who pursue this difficult calling in part because they have a strong rebellious or independent streak in the first place? That could indeed be like herding cats.

Ann Landi

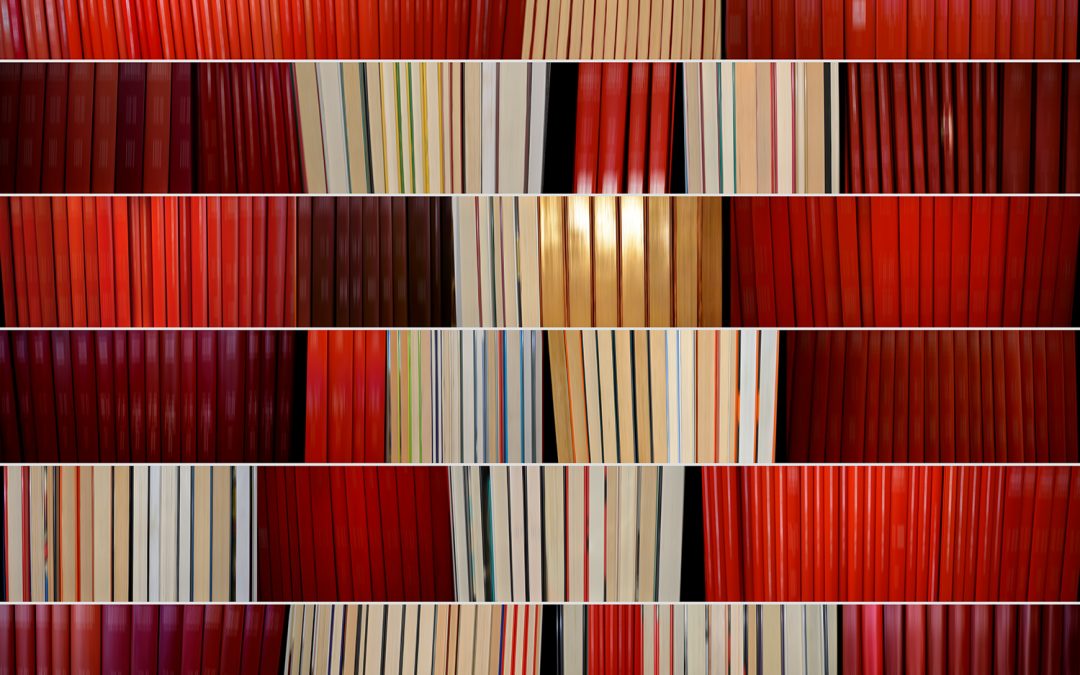

Top: Danae Falliers, Reverse 30, from the “Library” series (2016), archival pigment print on rag paper

I think that there is a paradigm shift occurring with artist beginning to embrace the ‘creative class’ model of managing their art career. You see it with artist selling directly from social media, and from high end artist led art fairs, such as the Accessible Art Fair, The Other Fair, ArtRooms, and Moniker Art Fair (interestingly, all of these started in Europe) to artist forming coop’s specifically to show at major art fairs.

The beauty of this model for artist is that it’s not based in competition with other artist but instead is collaborative, and most importantly, it gives the artist complete power in how they manage their art business.

Ann, having worked with a few dozen galleries during a thrirty-year career and found most of them to be disappointing, I have relied heavily on social media to market my work over the last few years. Believe me, with so many options now this does not get any easier! As terrific as it would be to find a gallerist who works as hard as I do, who thoroughly knows my work and can sell to important collectors, I doubt that such a person exists. Unfortunately, artists – at least this one – have to do it all.

I know it’s not easy, Barbara….the whole gallery model is changing so rapidly. I’ve covered the art world for years and years, and see so many good people who never “hook up” with the right venue. There are some weird object lessons in this game: no one paid attention to Louise Bourgeois till she was in her 70s. Carmen Herrera makes the cover of Modern Painters at age 101! The only comfort is that you get to do what you like to do, come hell or high water, and at some point the world might pay attention. But there are no guarantees….