No one claims it’s easy, but it is possible to combine two of the world’s oldest callings: artist and mother

Way back in the 1980s, in the era of linebacker shoulder pads and dressing for success, I worked on a short-lived publication that billed itself as the first magazine for “professional women.” The sorts of topics we addressed fell under the rubric of “having it all”—how to be a good mother, a sexy and devoted wife, and an ambitious breadwinner. Much to my surprise, given the huge sales of Sheryl Sandberg’s recent self-help bible, Lean In, it’s still a hot topic among women (I’m not excluding men from these pressures, but did you ever hear of a guy wondering if he could “have it all”?)

For artists, it’s an even thornier dilemma, perhaps because the emotional investments of both art making and family life are so high. Nor have there been a whole lot of role models to lead the way. Of the five outstanding painters who were the subjects of Mary Gabriel’s Ninth Street Women, only one—Grace Hartigan—had a child, and she turned him over to his grandparents to raise because she saw motherhood as incompatible with the sort of bohemian life she longed to lead. Most of the female icons of 20th-century art—like Georgia O’Keeffe and Agnes Martin—were childless. And the feminist generation of artists did not put motherhood high on the list of goals. When she had her son 24 years ago, remarks Melissa Stern, “there was still the feeling that you had to choose between motherhood and your career.”

That perception has changed and is changing to the point where a high-profile artist like Michelle Grabner can build an entire oeuvre around motherhood, and legions will rush to her defense when a New York Times critic dismisses her as a “soccer mom.” Which is not to say that the balancing act between the creative soul who needs unfettered space and time and the nurturing parent is easy. “The myth has persisted that to be an artist is to live a very selfish and self-involved life,” says Stern, “and to be a good parent you have to be willing to give and give and give. And give without resentment. That’s not easy, but it can be a fundamental contradiction.”

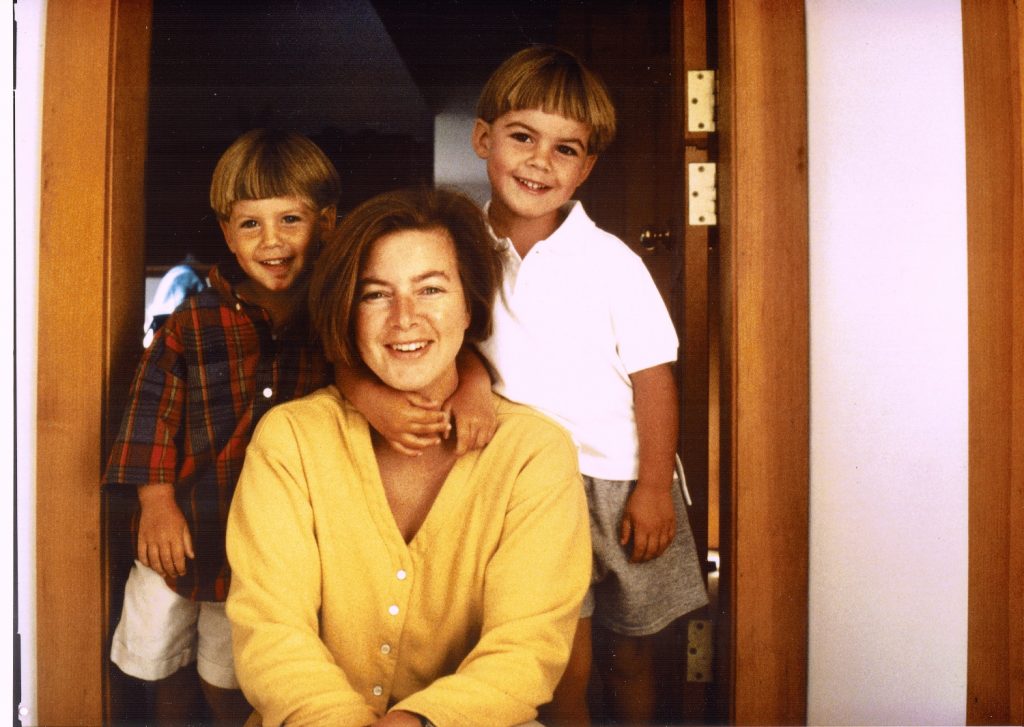

From left: Rebecca Urban with her mother, Jeannie Motherwell, Helen Frankenthaler, and Jeannie’s sister, Lise Motherwell

Of the ten women interviewed for this report, however, none seemed to feel that her career had suffered unduly from becoming a mother, no matter how difficult the circumstances—and those could range from abandonment by a husband to taking significant time off to care for a sick child. Jeannie Motherwell gave up her painting career for about 14 years, with much of that time spent as a single mom, to raise her daughter, whom she calls her “true masterpiece.” But she says the years away from the studio were necessary because she hadn’t yet resolved her identity as the daughter and stepdaughter of famous forebears (Robert Motherwell and Helen Frankenthaler).

It’s probably hardest to balance mothering and a career for women whose incomes are necessary to support a family, or who are in some cases the main breadwinner of the family. When she was in her early 30s, with two small sons, Grace DeGennaro says she was “always teaching part time but always kept a studio practice going.” When she had only one baby, she took him to the studio; when there were two, she went to the studio after her husband was home from work. “We were stretched pretty thin,” she admits, “but it was all important to me. There were points when my work wasn’t as strong as it could have been, because I didn’t have the time. I naively thought balancing parenting and teaching and the studio would be possible, but something always has to give a bit.”

Many of Jackie Skzrynski’s drawings have expressed the complex emotions of motherhood. Shown here: Harvesters (2004), charcoal and colored pencil, 70 by 50 inches

“I was never not going to do art,” says Jackie Skzrynski, who has taught full-time for most of her career and raised two kids with her husband, a carpenter, in upstate New York. “I had what I called sacred studio time, three to four hours on a Saturday, when we had a sitter the kids adored. If you don’t have that time set aside, then you never get to it,” she says. “You have to learn to walk past the messy living room. You have to learn to forgive yourself. Getting time to be who I was helped me be a better mom because I was a happier person.”

Barbara Cowlin, pregnant with son Mathew, painting in her carport as her older son, Jeremiah, looks on

“I’ve always had a dedicated work space,” says Barbara Cowlin. “When my sons were growing up, I could convert the dining room into my studio. And I had to learn to blank out any worries about my family. When I go in my studio, that switch still comes on. I envision myself as being enclosed in a bubble that excludes everything else.”

Changes in Imagery

Not surprisingly, becoming a mother can mean a change in subject matter, artistic process, even color choices (not to mention a switch to less toxic materials). During childbirth, Melissa Mohammadi says she had a dream that still resonates in her work. “When I had my first contraction, I felt the creator’s hands on my body, trying to make this baby,” she recalls. “So with every contraction I would say ‘Yes!’ And I had this strange 12-hour series of visions during labor. I could see the earth forming itself—mountains pushing themselves off the surface. As the baby was crowning, I saw volcanoes.

“My work is as intuitive as that labor process,” she says. “I became more aware of how things grow, gaining a deeper awareness of the creative forces of life. Being a mother has completely changed how I draw, and how art comes through me.”

When her children were small, Skrzynski says she was “confronting anxieties about motherhood and parenting” in her art in a series of drawings she calls “Hybrids,” which are half-human, half-animal and often confront pregnancy in frankly shocking ways—such as an image of a reclining nude with eight breasts, suckling piglets. Or another reclining nude whose head explodes into feathery fronds, which a pair of naked toddlers pluck from her neck. “I think it describes art and motherhood to a T,” she says.

Andrea Broyles has found over the years that her three children are often a source of inspiration. When they were little, she did a series of four- by five-foot pieces based on puzzle pieces her kids played with. As they grew up, she confronted her feelings of loss when they left the nest. They have even proved a helpful audience. “I could have conversations with them because they come from a different perspective. I’m not shy about showing them nudity, or whatever I was working on. And I had some very helpful critiques from them.”

Andrea Broyles’s Leaving (pastel on paper, 22 by 30 inches) was inspired by her son’s transition to manhood

Brenda Zappitell says that having kids awakened “a personal confidence I take in my work. I figured out that I could do more than I expected by having children, and because of them I’ve gotten to know myself better.” She adds that “mothering affects my color choices. The whole thing about being a mom is trying to find the upside of everything. I’m not the kind of person who’s going to create really dark paintings. That may be why my work tends to be on the joyous side, because I’m always trying to be uplifting for my kids.”

“My work has always dealt with ideas about childhood and memory,” says Melissa Stern. “That’s just a fundamental aspect of my approach.” As her son entered his teenage years, it became clear that he would become a writer (he’s now in Los Angeles, successfully engaged in that career), and Stern found herself with an unexpected collaborator for her projects, like “The Talking Cure,” which incorporates scripts read by actors to accompany the sculptures in the installation. “We did a one-of-a-kind artist book called Nightmare, and I’ve done the graphic design, posters and advertising, for his plays. He wrote a theatrical treatment of ‘The Talking Cure,’ and we’re now working on a book together.

“Having a mother who’s a working artist has made him a far savvier young artist than I ever was,” she says. “He understands what it takes to be a professional, having grown up in this household.”

Making It Work

The good news for women who are considering or are now actively balancing motherhood and careers is that it’s much more accepted, even commonplace, in the art world and the world at large. Dealers and curators are moms too, and have complicated lives and childcare arrangements. “Women are now bringing babies to openings,” says Stern. “Twenty years ago, you didn’t bring children to art events.”

Still, this is not a culture which is especially accommodating toward families, or of artists in particular. “In our society, there is no support for artists, whether you have kids or not,” says Cowlin. There are no stipends and housing allowances, as is the case in England or the Netherlands. And as art courses are eliminated from the school systems, she adds, “we’re raising generations of children who really don’t know what it is to be an artist.”

Lelsie Kerby used her daughters and their friends as the basis of a series called “To Whom It May Concern”

The good fortune of children who do have parents who maintain studio practices is that they see the discipline that goes into being an artist. “I’ve always made my daughters part of what I’m doing,” says Leslie Kerby. “When I had my own businesses, I took them to my office, and so when I embarked on studio work it was not completely different in terms of time. And they always participated in my life as an artist.”

Carving out what Skzrynski calls “sacred studio time” is perhaps the biggest hurdle artists face when they become new parents. “Figure out a way to get into the studio, even if it’s only for 20 minutes a day,” says Broyles. “And don’t leave your work until you feel confident you can stop at a certain point. If there’s something unresolved, it’s hard to get back into a flow.” On the plus side, when you do find the occasions to get back to the studio, your time becomes much more precious. “Knowing my kid would be home in three hours forced me to become more focused,” says Stern. “And being an artist-parent is a true test if you want to be in it for the long game.”

Even if you are not making art while raising kids, find a way to stay connected. “If you can do some kind of art-related position that puts you in touch with artists and keeps you involved with the art world,” says Cowlin, “at least your mind is still thinking along that track.”

And above all, ignore the naysayers. “I heard more than once that a real artist doesn’t have kids,” says Broyles. “You’re just ‘a housewife with a hobby.’ Don’t listen to that. You can be both a mother and an artist at the same time.”

There are many resources for mothers, perhaps even for artist-mothers, in your community (or you can start one). If you’re looking for some online help, Melissa Mohammadi recommends An Artist Residency in Motherhood, which bills itself as “a self-directed, open-source artist residency to empower and inspire mothers who are also artists.” The site contains good tips for creating a do-it-yourself “residency,” holding yourself accountable to hours and progress in the studio, and finding a mentor to see you through the difficult times.

Ann Landi

Top: Berthe Morisot, self-portrait with her daughter, Julie (1885), oil on canvas, 28 by 36 inches

hi ann,

your motherhood report is brilliant!! a quick share; i was a single parent ever since august, my son was 10 – he is now 33 and a mathematical physicist. he is my best friend and a huge support of my art. what i could pass on is the lesson i finally learned which was when i passed thru the door at home from my studio – august was my priority and i left all the biz in the studio and he was my focus.

life is amazing!!

thank you.

Magnifique

Wonderful article. Brought to mind my own experiences as a mom and artist. So important to hear other women artists’ stories!!!!!