Compared with the duration of empires past—like those of ancient Rome or Great Britain—the U.S. occupies a relatively tiny span of time, a little more 234 years as the great democratic experiment, if we date the founding of the country to 1776. And so our monuments and memorials have tended to celebrate only a handful of epic events: the American Revolution, the Civil War, the First and Second World Wars, Vietnam, and Civil Rights. (Oddly, most of the statues celebrating the Confederacy are mostly of recent vintage, erected by groups eager to rehabilitate the memory of the South. The New Yorker reports that there are a whopping 700 of them—or were before the recent wave of protests spurred their removal.)

For the most part, until the last year or so, monuments of all sorts have gone unremarked and undisturbed. “A turning point in the broader public imagination came with the Unite the Right rally in August of 2017, when white-nationalist groups went to Charlottesville, Virginia, to protest the removal of Confederate statues and memorials,” claims Hua Hsu in The New Yorker. “The protests turned violent, resulting in the death of a counter-protester, Heather Heyer.”

And the violence has continued, leading to yet more statues toppling, followed by Donald Trump’s executive order to establish a “statuary park named the National Garden of American Heroes, slated for unveiling in 2026 and intended to display realistic statues of, among others, John Adams, Daniel Boone, Amelia Earhart, Davy Crockett, Martin Luther King Jr., Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton, Audie Murphy, Ronald Reagan, Antonin Scalia….and on and on.

With the focus on hunks of bronze and marble that we have spent most of our lives ignoring (quick! can you name the subject of any statue in your nearest park or plaza?), now seems like the perfect moment to rethink the monument. And so I threw out the challenge to site members, who responded enthusiastically with a wealth of ideas in many different mediums. As seen in Part One, artists proposed celebrations of nurses, sports heroes, and “color and movement in space.” Here’s our second round, with suggestions every bit as imaginative and provocative.

Who says public tributes have to be dull?

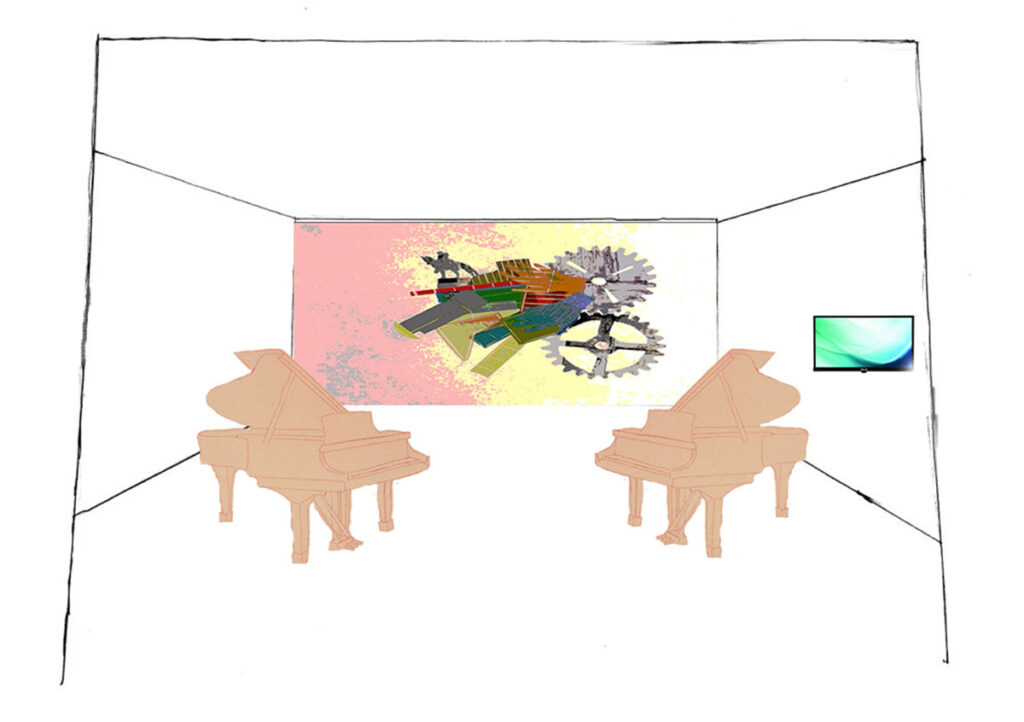

Leslie Kerby: Monument to the People is a memorial to honor all Americans. Similar in some ways to the tomb of the unknown soldier, this monument will serve to celebrate Americans, nominated by any American. The monument will be housed in a three-sided pavilion. Visitors can walk up to a monitor with a keyboard recessed in the wall and enter the name of any person they would like to honor. The name will be added to an evolving database and projected, along with other names in a video format, on to the back wall of the pavilion. The video scroll of names will be activated by visitors striking the keys (playing a song—from “Chopsticks” to the blues to Mozart) on the pianos placed in socially distanced locations inside the pavilion. Hand-sanitizer stations will be available to keep both the computer keyboard and piano keys clean. Twice a year—July 4th and Labor Day—two professional pianists will play a medley of songs of their choosing, the length of which will be determined by one full projection of all of the names in the database. This televised celebration will be followed by fireworks.

Bob Clyatt: Monuments have always been aspirational. We may be commemorating something from the past but contextualized as something we admire and need today to help us chart a course into the future. What we need today, I believe, is conversations between and among all kinds of Americans who have stopped talking to each other, stopped wanting to know. How to build a monument around conversation? Create a space where conversation can feel comfortable and naturally flow, and prompt this with diverse Americans engaged in conversation. These images are studies I’ve been developing for a “Conversation” series. They were envisioned for interior and more personal kinds of spaces but may help as a stepping stone to a large-scale environment dedicated to a better national conversation, to more and better conversations among all of us.

The heads shown here are life-size stoneware and patina on steel stands; the flag behind is 25 by 48 by 5 inches, wall-mounted Hydrocal and Carrara marble. Installation dimensions could vary, with placements trhree to four feet apart—creating a sense of reaching out from separateness into conversation.

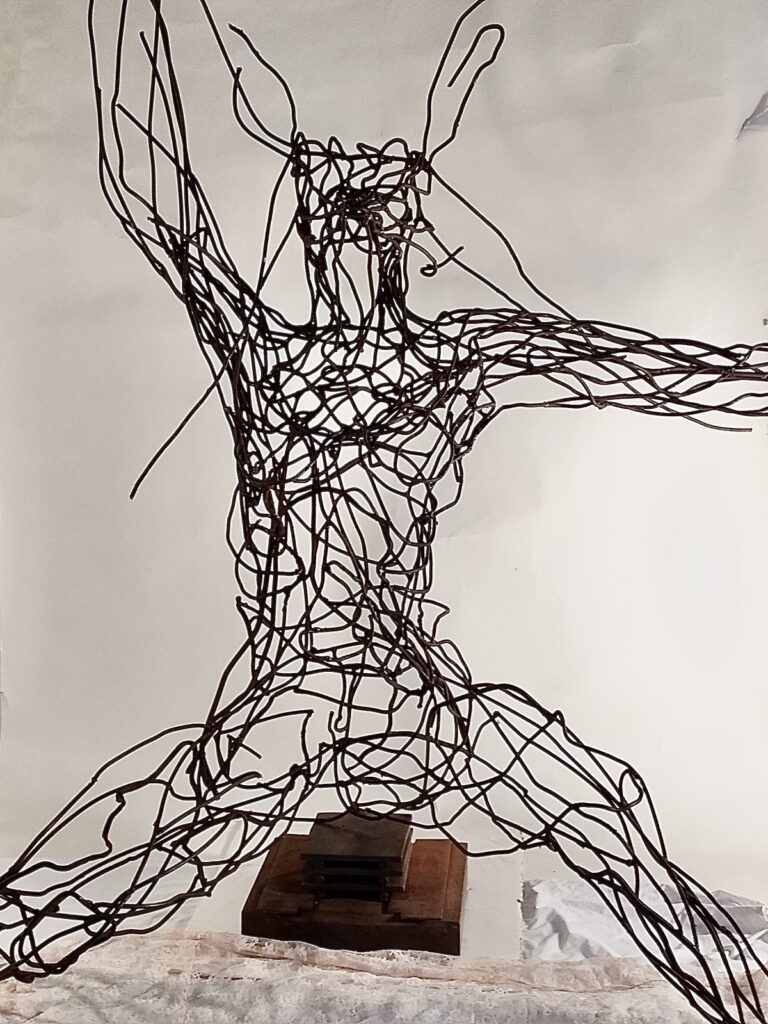

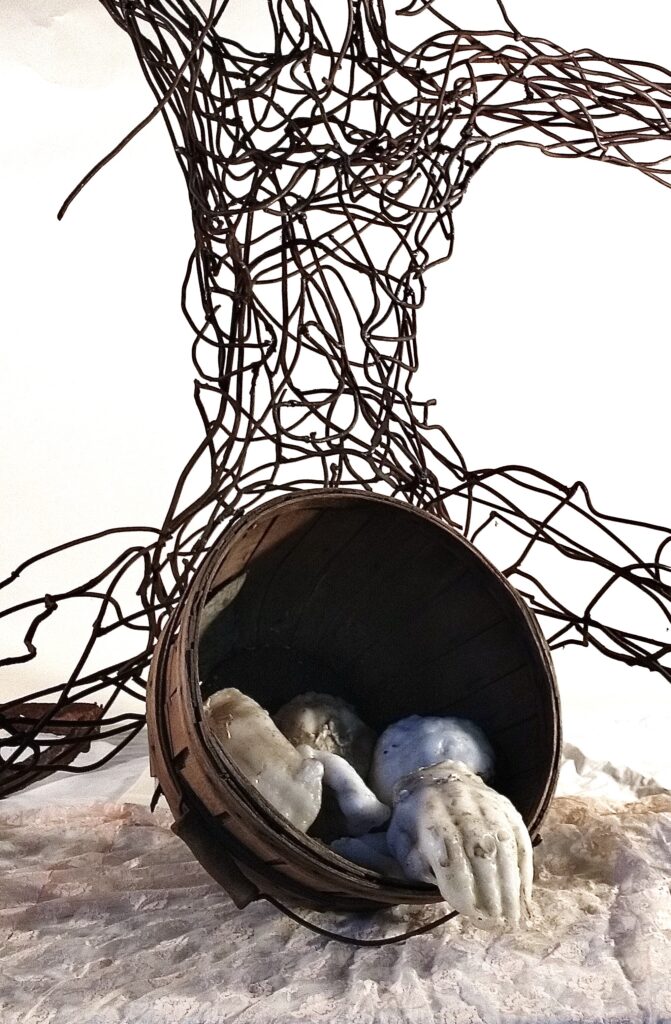

Susan Bennett: Making the Deer Goddess has been cathartic for me. I grew up in a rigid patriarchal family, the oldest daughter with five brothers. I worked in the trades as a pipe welder for five years—which was not the answer and neither was marriage, nor alcohol, nor searching for peace in sobriety through a spiritual program, but it did bring spiritual wisdom. All I had to do is ignore yet another repressive patriarchal system. These experiences left me chafing at the bit and looking, it seems, my whole life for freedom. The Deer Goddess has been an ongoing meditation for me since around 2003. In fact, when I finish it, I will most likely be at the end of this particular journey. She is an icon representing ancient matriarchy, heroic deeds, and a connection with spirituality. I am now in my 70s and embrace all that freedom brings, which is mostly a quiet joy from the little things that invariably show up every day. The metal for the body is ¼-inch steel round stock; the antlers are 1/4 inch stainless steel plate. The hands, added in a later version, are plaster casts of some of the men in my immediate family.

Ellen Weider: I made this painting in response to the death of John Lewis and his exhortation to us to “walk with the wind.” His life and words were an inspiration to me and were in my mind as I worked.

As a monument, I envision this constructed in painted bronze, in the same colors as the model, and set in a bronze base. The monument could be single sided or sided. If double sided, the geometric forms would be repeated on both sides. In either case, the lines delineating the shapes would be incised in the bronze, including the lines that form the main geometric shape and run thorough the center of the smaller shapes. The monument could be attached to the base on the lower left to cantilever upward from there, or the lower edge could be completely attached to the base but set at an angle that maintains the line of the main shape.

The entire monument is infused with a lightness; the shapes seem to be at once taking off from, touching down on, and soaring above the larger form, while retaining a connection to each other. There is a sense of a communal activity that in turn evokes a sense of possibility and transformation.

Ellen Weider, Walk with the Wind (for John Lewis), 2020, acrylic, gouache, and graphite on linen, 16 by 20 inches

Sassona Norton: Fifteen Minutes of Fame, as seen below in my studio, embodies two contradictory forces: the winning gesture of Number One and the image of its cracking. The two forces happen consecutively, and as in most cases, the last to take hold wins the game. No one escapes the passing of time, but for those on the power pedestal, the fall seems deeper, and more unexpected. Andy Warhol’s quote about fleeting fame touches on the dynamic forces that alter historical and societal perceptions. The hero of yesterday can be the villain of today. It is comforting to know that at times our salvation lies in the formation of the cracks.

Andrea Broyles: We need monuments in public spaces that represent freedom, equality, peace—or are simply just plain beautiful. This image came to me while I was considering what would be tranquil and inspiring. Tower of Hands is a column of many hand shapes, arranged in a pattern covering the concrete column. The hands are bronze in a variety of patinas and thus not indicative of any particular race. The positioning creates a rhythm and energy as they reach upward to the sky. They represent the mass of humanity extending toward hope. It is a water feature, in which flowing currents symbolize peace, renewal and purification of the soul.

The column itself is made from concrete. The bronze hands are welded onto the metal sheath wrapped about the center, and water gently flows out from the top and trickles down the sides. The column is set in a large receptacle at least eight feet wide. The water spills over the edge into an infinity pool, giving the illusion that there is no boundary.

Candace Compton-Pappas: This is a memorial honoring the lives of the assaulted, missing, and murdered Indigenous women in North America. A 2014 report called “Missing and Murdered Aboriginal Women: A National Operational Overview” found that more than 1,000 Indigenous women were murdered over a span of 30 years. According to Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women, (#MMIW), Native American women are murdered and sexually assaulted at rates as high as 10 times the average in certain counties in the United States—crimes overwhelmingly committed by individuals outside the Native American community.

The monument is a rendition of a dead cedar tree, it rises 30 feet tall and is made of marble. The trunk is carved, from multicolored marble, and the branches are cast from molds, using bonded marble. Mixed in with the bonded marble is a reflective material (metal flakes, perhaps) that will catch light. The branches will be attached to the trunk using a steel rod/dowel. There will be a small indiscernible space between the branch and trunk, exposing the rods to moisture and rain, causing it to rust over time and sending rivulets of rust down the trunk of the tree.

Thus the branches will be reflective, and the trunk will have streaks of earth color—from the rust—slowly over time coloring the marble. My hope is that the materials be sourced from used or discarded marble.

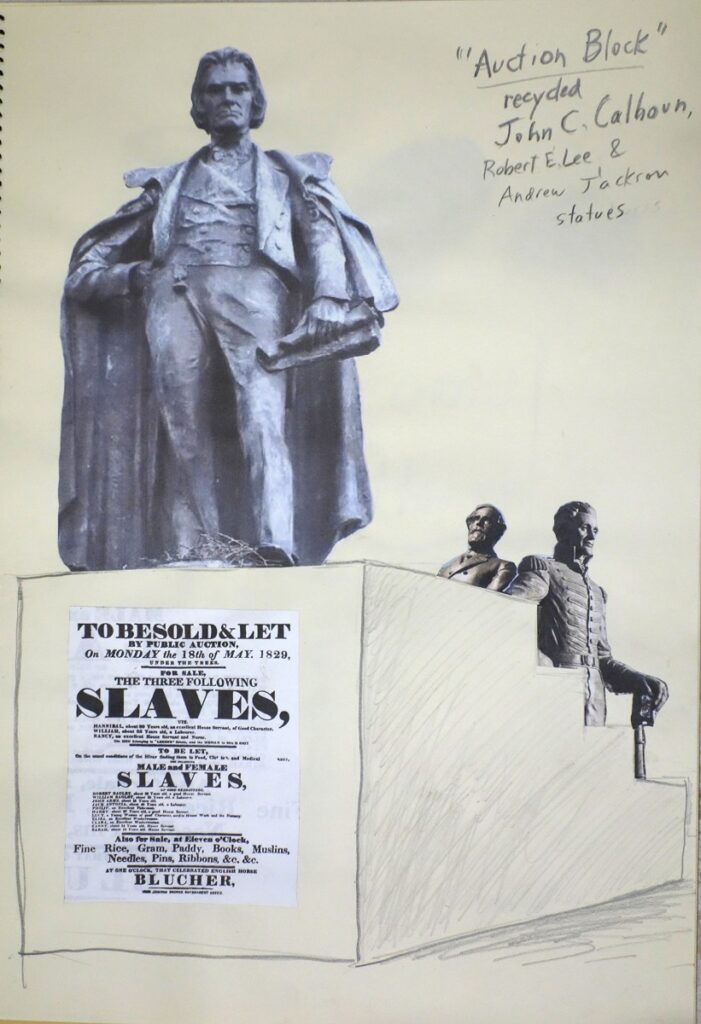

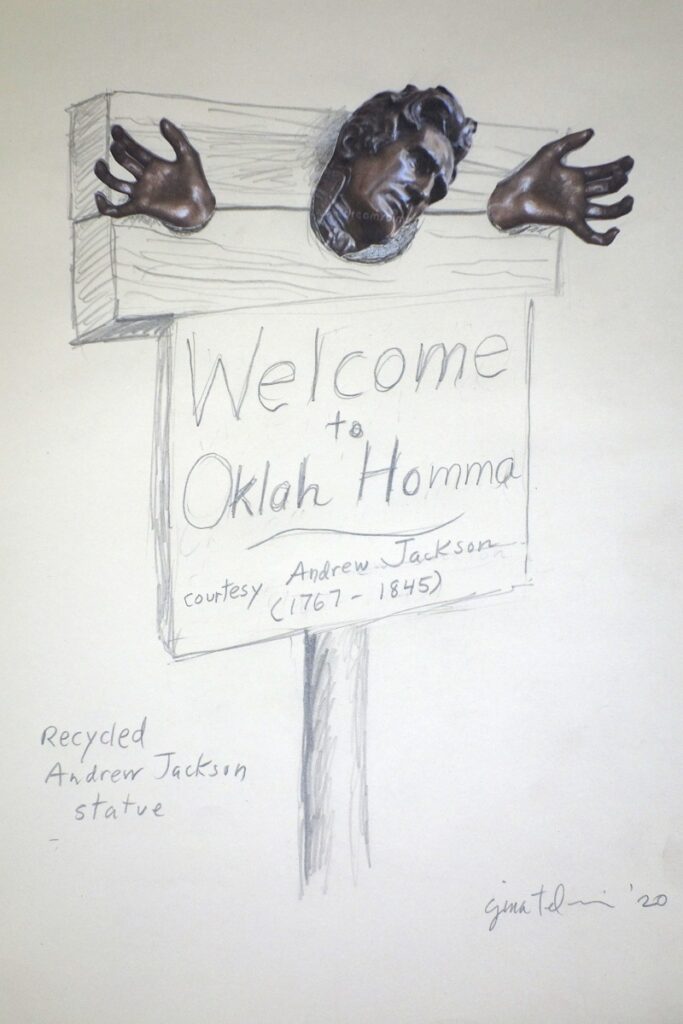

Gina Telcocci: My ideas are meant primarily to make use of existing statuary that has been removed due to evolving standards of worthiness. They are about recycling de-installed, presumably racist figures from history into newly contextualized statements about that history.

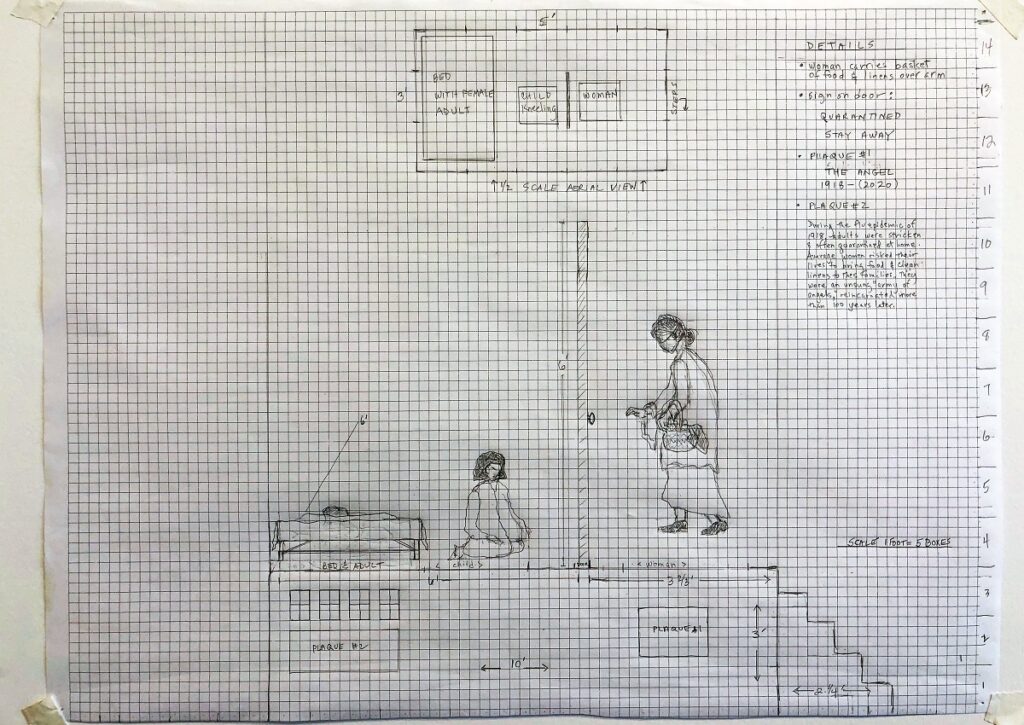

Cora Jane Glasser: My grandmother was one of many women who risked their lives and exposed their own families to bring food and supplies to quarantined patients. The afflicted families often lived in tenements. trapped in small spaces. As with today’s pandemic, the outbreak in New York City was swift and severe and overwhelmed hospital facilities. So many families had to remain locked down at home with little ventilation. My grandmother lived in Brooklyn with her own young family, including my mother, who was four in 1918, and my uncle, who was born that year. Yet she would prepare food and launder sheets and deliver them to quarantined neighbors. Others criticized her for endangering herself and her family. Her response was that she had no choice. It was the right thing to do. Without food these people would starve. I heard that she was called The Angel, and I always believed the story because she was the kind of person who would do such a thing. But it was like personal family mythology from long ago and far away. It was not until the Covid-19 pandemic that I recalled the story, and it suddenly became relevant and full of life. Surely, she was not alone. Surely there were countless women like her. They remain nameless and faceless. Their numbers are now further enhanced by the many who more than 100 years later performed the same kinds of good deeds. Not the health-care workers and others whom we celebrate daily and whose faces we see on TV, but the average person of strong character and good conscience who knows right from wrong, and, as my grandmother saw, taking the risk to help another as an easy choice.

Therefore I am entitling the proposed monument The Angel and dating it 1918-2020. And, yes, make it in bronze or marble! It’s not a monument to a person, but to an idea, an ethic.

Top: Sassona Norton: Fifteen Minutes of Fame, plaster