Why is an art critic’s judgment better than yours—or maybe not?

A few months back I did a stupid thing on Facebook and opined that I did not think Amy Sherald’s portrait of Breonna Taylor was very good (check out the hands and drapery), and that I found her pose in a photo in Vanity Fair (on a ladder, beautiful bare legs fully exposed) problematic, wondering why a serious artist tackling a serious subject would present herself in that way.

Of course, I unleashed the hounds of hell, with Facebook “friends” wondering how I could call myself a critic. And I kind of wondered the same thing myself. Did two Ivy degrees in art history count? Did writing for ARTnews and the Wall Street Journal and other art publications for more than 20 years mean I had a better eye than others?

For answers I’m turned to my writer and critic friends, asking, What does it mean to have an “eye,” and why is your judgment better than the average museumgoer’s? Can you give examples of the way your critical faculties may have sharpened over the years?

Their responses were as varied as their personalities, and because I received quite a few, I am publishing this in two parts.

Eleanor Heartney: In a 1967 essay titled “Complaints of an Art Critic,” the late, not lamented Clement Greenberg maintained that aesthetic judgments were an involuntary response to the quality or lack thereof inherent in a work of art. He maintained “you can no more choose whether or not to like a work of art than you can choose to have sugar taste sweet or lemons sour.” That certainly doesn’t seem right, but then neither do the contrary ideas that taste is personal, subjective and essentially arbitrary or that judgments are elitist and the product of cultural imperialism. A more useful perspective is the reminder that criticism is an art, not a science and that it is informed by exposure to a wide range of art and artists, a decent grounding in art history and dialogue with other equally committed people. Arthur Danto used to say that judgments emerge within the context of a community. Our current discomfort with critique may stem from the fact that today the art community is as splintered as every other part of society. Can the rifts be healed? Until we have shared values again, criticism as we used to know it just may not be possible.

Franklin Einspruch: My policy is not to critique work that I haven’t seen in person, but come on. That Amy Sherald portrait, with Breonna Taylor all but floating in a gentle sea of hygienic blues, looks like an advertisement for menstrual pads. Vanity Fair commissioned Sherald to paint a subject that she would not have chosen on her own, and it shows – this is not a good Sherald.

Meanwhile, the magazine employs some of the world’s foremost experts on photographing women. For some reason the photographer put her in an outfit that suggests that she’s wearing nothing but the summer breeze between her work shirt and her sandals, then sat her down on a ladder in an awkward pose that puts her crotch at eye level.

Nothing about this works. The photo editor should have spiked the shoot. The managing editor should have spiked the feature. Sherald should have spiked the painting.

So, as they asked you, who am I to say so? The short answer is, Try to fucking stop me. The longer answer is, as I once wrote: “A critic is a quintessential member of the audience for art. He is not in a class above his fellows, but at a high point within the same class. His power is to be able to hang apt and moving words upon his experiences—experiences that are often hard to describe because they take place entirely outside of language. His eyes discern nuances. He has put himself in front of art many times. He has educated himself about it, its history and its philosophies.”

The average art viewer does not trouble to do all this work. A flair for language is perhaps not so uncommon, but the ability to hook language to the art experience seems to be rare. Having an eye, as it’s called, is a real phenomenon. This shouldn’t be controversial, as having an ear for music is not, and it’s analogous. But the contemporary art crowd is so allergic to hierarchy that they don’t like hearing it. I’m one of the few critics who is willing to argue that Clement Greenberg was right when he said that taste is objective, at least if you accept the split between the subjective and objective world.

If you don’t accept the split, and I don’t, then quality is a variety of presence, in a phenomenological sense, and taste is a skill we use to achieve that presence. That skill can be better or worse adverbially, and that presence can be better or worse adjectivally. The skill can be sharpened, or go dull. Those ideas were informed by Alva Noë and worked out in an essay I wrote in 2020.

I don’t know if having an eye is so unusual, but we’re living in a profoundly dishonest time. Without fidelity to his eye, a critic has nothing. A lot of criticism gets written in a spirit of faithlessness. Because of the politics of the moment, people expect you to pretend that this train wreck with Amy Sherald is a triumph, and clamor along with them for the canonization of Taylor. On the contrary, my willingness to critique Sherald is to take her seriously as an artist. The so-called right-thinkers would have me infantilize her, to pat her on the head like a five-year-old with a fresh crayon scrawl. They can disagree with me about this Vanity Fair effort if they will, but they shouldn’t mistake their conformity for conviction.

Francis M. Naumann: To have “an eye” is one of the most misused metaphors in art history. You can only have “a good brain.” What you see with your eyes tells your brain if what you are looking at is good or bad, and good and bad are exclusively subjective positions that are purely reflections of taste. What one person likes is not necessarily (or even remotely) what someone else likes. Of course, you can argue that “an eye” is an aspect of connoisseurship, but what exactly does that mean? It only means that when a person sees something they like or don’t like, it channels into a spot in their brain that is already educated and predisposed to understand what they are looking at. If you should wish to secure an attribution for a work of art, you can be taught what to look for. As the art historian Giovanni Morelli pointed out at the end of the 19th century, various artists in the 15th century painted ears a certain way, and if you know what that design is, then it can help you to attribute a painting. It’s not the person’s eye that is doing the heavy lifting. It’s his or her brain.

It’s for that reason that liking or disliking the work of Amy Sherald is meaningless, except of course for yourself and the people who trust in your judgement. An opinion is only a reflection of the person making it, no universal guide exists to determine if something is bad or good. You may not like the way she renders hands or drapery, but that means nothing, since it is only a subjective opinion, yours and those who agree with you. There are far bigger factors at play in judging her work, and technical proficiency is not necessarily among them.

Peter Frank: Why is my judgment better than the average museumgoer’s? Putting aside the slipperiness of terms like “judgment” and “better,” I’ll claim that my response to art is more complex than the average museumgoer’s because it’s my professional responsibility—and passion—to be as well informed as I can about what I’m looking at (and where, when, and why I’m looking at it). It’s my job, and it’s one of my greatest delights, to know as much as I can about, and around, the things I write about; to write about them as informatively, judiciously, and persuasively as I can; and to maintain such authority by sharing my knowledge and discretion effectively and dependably, through well-measured prose. I respect my subject matter and my readership (whether or not I like either at any particular time) and recognize that the respect due me in turn must be earned constantly.

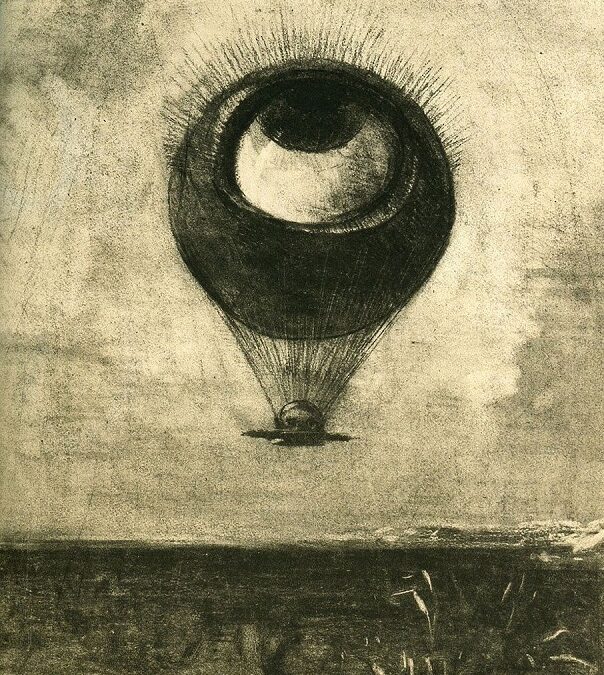

Top: Odilon Redon, Eye Balloon, 1878

Many good and some entertaining thoughts, thank you. The old adage, “when you change the way you look at things, the things you look at change” holds true. Learning to see art should push us past the arbitrary gatekeepers of taste and preferences. It takes practice; it takes experience.

I do think there is a “white gaze” much like the male gaze that was so passionately discussed 20 years ago. There are systemic sexist and racist structures within the art world, and that is undeniable. But that doesn’t make bad art good. I have no opinion about the work in question, but I do believe that your eye is more finely tuned than most. As one critic stated, we accept this with music critics and I would add food critics as well; so why not accept that looking at a ton of art for decades builds certain perceptive muscles that aren’t equal to everyone else’s?

It’s the current climate that takes issue with all inequality, some of which (like economic, food, and educational) are absolutely valid, but some of which are simply nature, experience, or hard work. I think a critical eye falls into the latter.

A work of art lives or dies, succeeds or fails in the moment of encounter. If it succeeds, it can even transcend its time, which (arguably) can make it great. My personal issue with political and identity art (though powerful and valid) is its ability to endure; to speak to those in the future. We should have voices of the moment; it’s crucial and one of the important functions of art. But we should also be able to discuss whether that -or any- work of art is good, great, important or enduring in a civilized manner. While the subject may be extremely important and relevant, the execution may be god-awful; and it’s okay to say so.

While I am sympathetic to Peter Frank’s position of expertise and from years of teaching and writing on art myself, I do think expertise is hard earned, but I tend to agree with Eleanor Heartney’s approach.

My comments do not relate to Sherald’s portrait which I have not seen, but art criticism is clearly both culturally biased and based.

It wasn’t that long ago when late Baroque (Rococo) art was seen as frivolous, only to be later reclaimed as illustrative of the culture it portrayed. In 1963 a symposium was held that debated whether Pop Art was reactionary because of its use of realism– a position few of us would hold today. The symposium had leading critics of the time including Dore Ashton, Peter Seltz, Hilton Kramer, among others.

Art criticism is not lodged in absolutes. It carries on a conversation lodged in its time and place. And that, in itself, is valuable.

I remember that you once dissed Camille Pissarro, so at least one time before your judgement has been suspect.

Terrific piece, Ann. Some interesting points of view expressed. I had no idea that you had gotten into “trouble” for voicing your opinions. It is a sad commentary on how parochial and closed minded the creative community has become. The space for civil discourse has all but disappeared and with that the opportunity for meaningful conversations that may express differing points of view

I love your repro of the pose Franklin! All the essays offered both reasoned and cogent comments on the subject. I think experience plus education almost automatically makes one a “critic” (or at least an expert) whether or not that’s a full-time vocation or not. To me what’s most relevant is understanding where any given critic is coming from. There are some film critics that consistently have the opposite reactions to movies that I do, which almost as useful as the ones that agree with me.

If taste (discernment) is subjective, then how do we account for universality? How do we arrive at universality? Passage of time. Until then, it’s all commentary, but we love us some commentary, don’t we?

I read critics as beginning a conversation and/or a thought process of taking up questions which lead not to the answers but to the next questions and so forth. For my purposes, the real critics are the ones who leave me who throw me up against the wall, slap me winding, leave me with something to wrestle with, get mad at, etc.

I’m not sure what “slap me winding” means, but in general I get your drift and thoroughly agree.

A critic is someone with a presumably educated opinion based on knowledge, experience, and yes, an eye, which is absolutely indispensable. However, everyone should function as a critic when dealing with art, and that personal judgment should take precedence over anybody else’s take or opinion of the work in question. It’s understood that opinions or reactions will differ, sometimes dramatically, depending on the viewer, but that’s just the way it is. The bottom line should always be how the individual person responds to the work, which does not require other people’s permission or approval, and those who are unable or unwilling to judge for themselves should probably not be bothering with looking at art. Art is simply an interaction between the viewer and the work, and what other people think need not come into it at all.

“Did writing… mean I had a better eye than others?”

Take the above paraphrase as a hint: it obviously doesn’t work like that.

At least know I understand the backstory for that picture of Einspruch, which is far more ridiculous than its referent. Good grief!

I am happy to print your comment complete with its grammatical mistakes (a “paraphrase”? no, actually not; “know I understand”). I don’t think you belong in this discussion without an interpreter. AL

“Grammatical” mistakes? No, actually not… LOL

KNOW is a typo for NOW, I hope the rest is clear enough, cheers.

“Did writing… mean I had a better eye than others?”

This is not a “paraphrase”; it’s an abridgement.

Further, the antecedent for “it” is totally unclear.

I suggest you buy a copy of Fowler’s Modern English Usage before you submit more comments. Or at least proofread your work before you send it off.

Thanks for addressing this. I read the post first in an aggregator, “Old News.” When I opened the Sherald image, I had a jaw dropped OMG moment. Worse than you describe and I mean the layout, not the painting which I have seen in other contexts and it’s not my favorite, but who could see it at all in this art directed nightmare, Who wants to be presented this way and who are they trying to reach??

As for critics, I think of them as art informers. The word critic is fun to use, but useless. i respect the writing and the writers and think they add a valuable dimension to the art. I look forward to part two.