It’s a rare artist who finds her medium and her methods early and then sticks with them, with little deviation, for more than four decades. But so it was for Susan Schwalb, who discovered the art of drawing with silverpoint in 1973 and never looked back. She was spending a summer in the Hamptons with a group of other artists, and was then engaged in doing pen-and-ink drawings, “looking for the finest possible line, as she puts it. One of the others in residence had a metalpoint stylus that she used on a specially prepared surface, Schwalb recalls. “When I was back in the city, I immediately bought the same materials and started to draw.”

Metalpoint—most commonly seen in silverpoint drawings, but other metals like gold, copper, and aluminum can be used as well—has been around since medieval times (the medium is in part what lends Leonardo’s drawings of angels such a breathtakingly ethereal quality). But Schwalb is one of the few to forge a purely abstract vocabulary, influenced by Minimalism and stripped-down esthetics recalling Agnes Martin, qualities that make her a standout among contemporary practitioners of the medium. As she notes in her artist’s statement, her approach is often painterly: she is able to “obtain soft shifts in tone and color reminiscent of the transparency of watercolor. A shimmering luminosity creates what often appears to be a three-dimensional, undulating surface.”

Schwalb knew from the age of five that she wanted to be an artist. She describes her mother as a “semi-professional,” who made “wonderful jewelry and ceramics” and who was also head of cultural affairs in the Bronx (her father was a judge and a lawyer). “I went very early with her to museums,” she recalls, “and traveled all over the city by myself by the time I was ten or eleven, taking after-school art classes and going to the Met on Saturdays.”

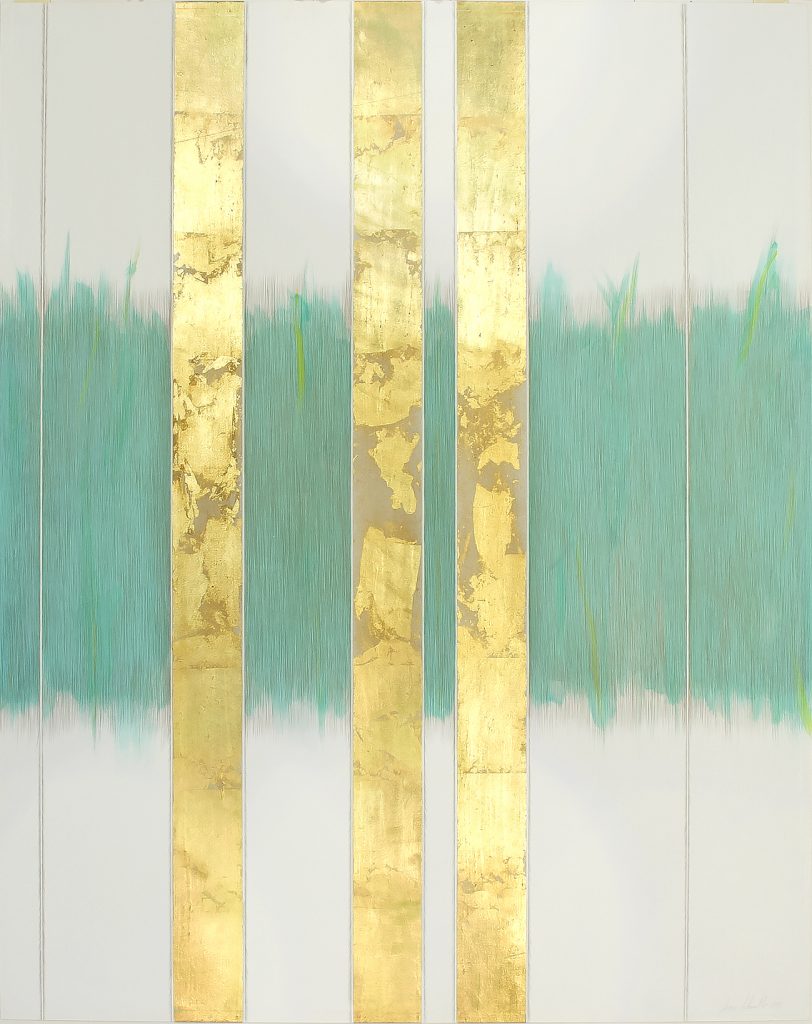

Poplar #9 (1991), silverpoint, gold leaf, acrylic gesso on Strathmore plate finish Bristol, 29 by 23 inches

Eventually she attended the High School of Music and Art in Manhattan, one of a handful of prestigious public schools in the city, then located in a rough neighborhood near Harlem. “I was determined to go to this school, even though my parents thought it was dangerous.” For college, she decided against urban schools like Pratt or Cooper Union, which would have meant living at home, and instead headed for Carnegie-Mellon University in Pittsburgh, PA. Schwalb majored in fine art and graphic design, which helped her land a job with Dell Publishing after graduation.

The experience there led to freelance assignments in graphic design, but, she says, “I never gave up drawing, even when I was working at Dell. I always had a drafting table at home.” In 1971, she took the summer off and spent it on Cape Cod, making art full time. She had the right stuff—the discipline and perseverance—but didn’t show much before 1975, other than in nonprofit and artist-run spaces.

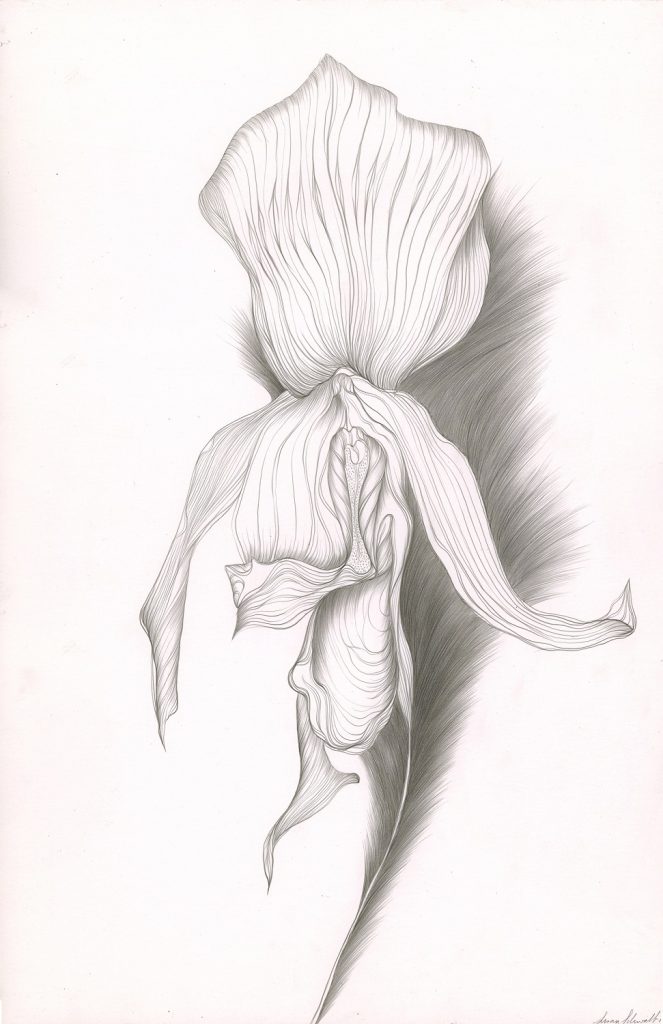

She was also involved with the women’s movement in the ‘70s and her earliest subjects, orchids, had a deliberate and decidedly female quality. “During the first year I drew from one dried flower exclusively, seeing it from many points of view,” she recalls on her website. “It seemed to me a symbol for myself and for women.”

In the years since that initial “Aha!” moment, Schwalb has experimented with various ways of stretching the metalpoint idiom. “I began to scratch and tear the paper and then added smoke and fire as part of my technique, juxtaposing the very precise silverpoint technique with an emotionally free and dramatic element,” she writes. By the mid-1980s, she was combining color with metalpoint, making large-scale works in which burning no longer played a role. In the years following, she returned fleetingly to representational imagery, like small feather shapes, and later a “Poplar” series which had its origins in a painting by Monet. Other works in the ‘90s took their inspiration from desert landscapes or juxtaposed brushed gold leaf against lines of silverpoint.

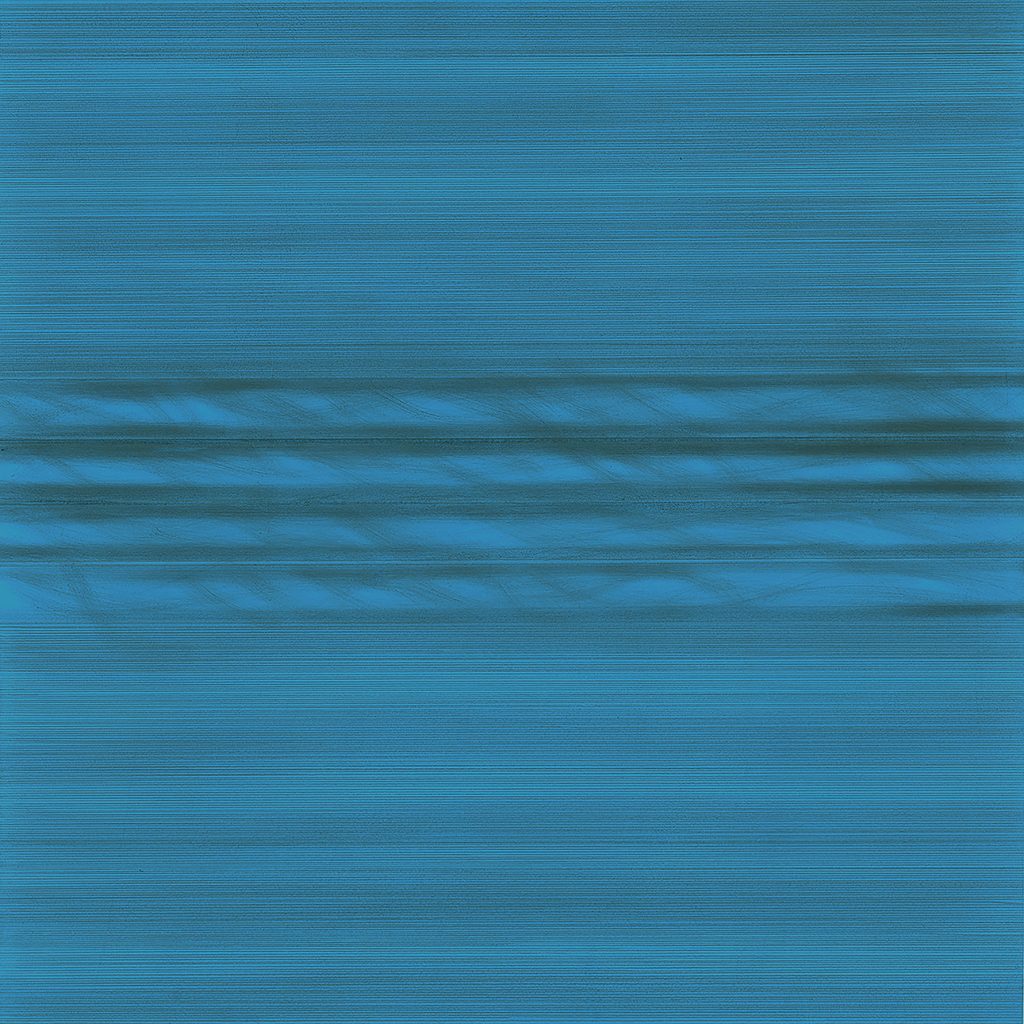

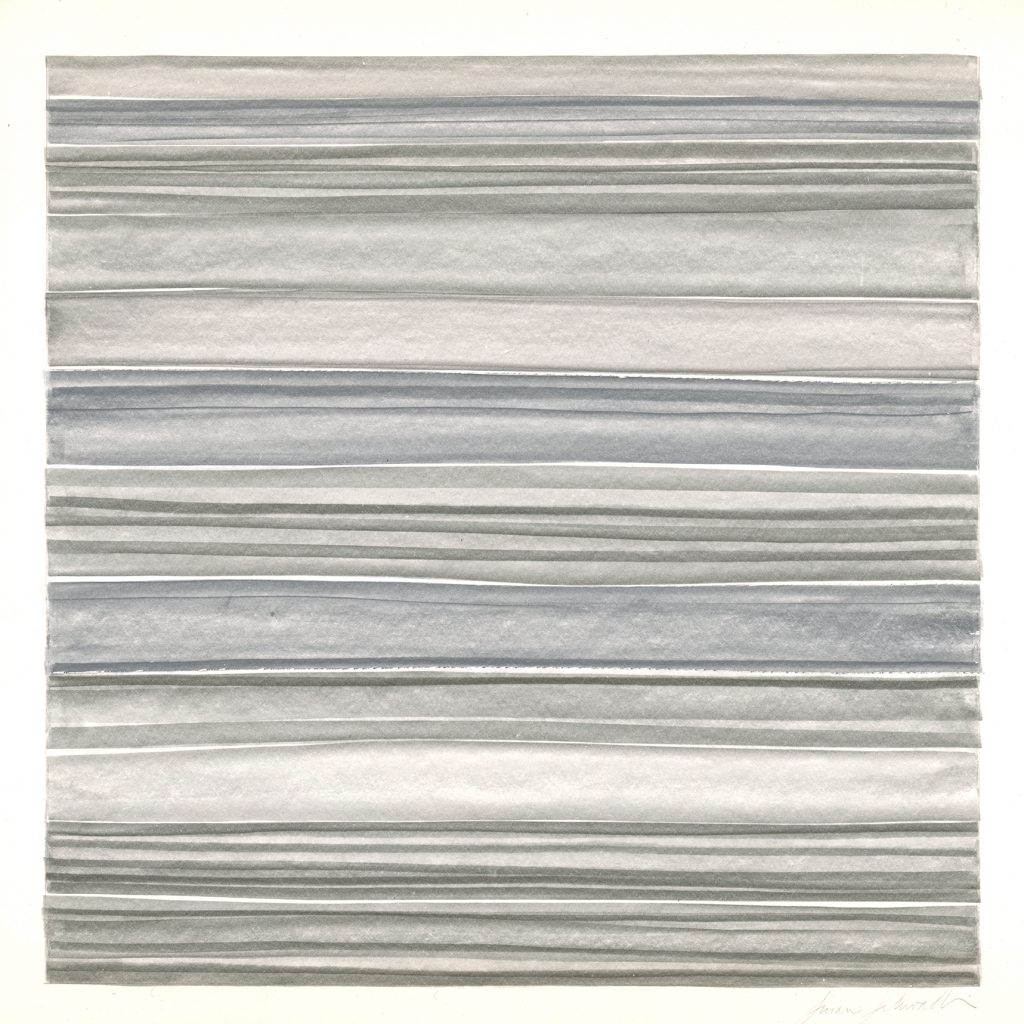

More recent works, combining a colored gesso ground with extremely fine lines, may seem most reminiscent of Agnes Martin’s large, resolutely abstract late paintings—which were no longer based on the grid—but Schwalb’s approach evinces a greater sensuality perhaps in part because of the tints added to acrylic paint to achieve a colored ground and a more wavering, spontaneous attitude toward the imagery.

Harmonizations #8 (2017), silver/gold/aluminum/copper/brass/tin/platinumpoint, and black gesso on panel, 24 by 24 by 2 inches

Currents #4 (2018), aluminumpoint, aluminum wool pad, cerulean blue gesso, on paper on Arches paper, 18 by 18 inches

In 2015, Schwalb was one of only three contemporary artists to be included in the National Gallery of Art’s show “Drawing in Silver and Gold: Leonardo to Jasper Johns,” which explored the history of metalpoint and included such immortals as Dűrer, Rembrandt, and Raphael (the show traveled to The British Museum). Her first book, Silverpoint and Metalpoint Drawing: A Complete Guide to the Medium, co-authored with Denver artist Tom Mazzullo has just been published by Routledge/Focal Press, in Britain and the U.S. The volume includes chapters on history, technique and materials, and a gallery of contemporary artists who work in the medium. And her next show will be in May 2019, at Patrick Heide Contemporary Art in London, where she was invited by the Courtauld Institute of Art to be a ‘Visiting Expert’ (a program that ask distinguished people in the visual arts to give a public lecture, along with seminars and workshops with graduate students).

Schwalb now divides her time between an apartment in Manhattan, a studio in Long Island City, and a home in Watertown, MA, which she shares with her husband, a composer and professor emeritus who recently retired after 52 years at Brandeis University. Times for her have changed considerably, and for the better. “In the ‘70s nobody wanted to show women and nobody wanted to show works on paper. I felt like I was being punished for working only on paper.

“My career is self-made,” she adds proudly. “I’ve never had a major dealer behind me, although that certainly would have helped.

Ann Landi

Top: Winter Solstice #12 (1990), silverpoint and acrylic on Arches paper, 24 by 52 inches

Ann Landi you are a super special person to create this wonderful blog about art. I am sure that many people appreciate it and more than you might know.

Thanks again.

Thank you for doing a wonderful article on such beautiful work.

Her work is wonderful. Thank you for sharing.

Susan has been a personal role model of mine since I first met her in the 1980s. She is a persistent, indefatigable woman artist who believes in her work and stays the course. Susan has made her own well deserved success. Thank you, Ann, for shining your spotlight on a superb artist.

Thank you Adria!!!! I look forward to visiting your studio again. S.

love this works the orchid phragmipedium on top a marvel will try this techniques..congratulations!