Get a jump on the season with a beach-bag full of memoirs

Perhaps because I’ve been working on one of my own (“Rotten Romance,” dispatched via Substack every Sunday), memoirs have been much on my mind. For purely recreational reading, I often prefer first-person accounts over novels and biographies, if only because the author’s voice and personality shine through in a way that’s not possible with more distanced efforts. I recently finished Francis Naumann’s delightful recollections of his student years and his friendships with many names familiar to me from my own studies in art history and my work as a journalist in New York—Leo Steinberg, John Rewald, Robert Pincus-Witten, and Robert Rosenblum (if you think this list is heavy on the testosterone, remember that there was a time when not many women had a chance to attain star power in academia). Naumann was lucky to count Beatrice Wood, the ceramist who pursued her art right up till her death at age105, among his circle of intimates, and his recollections of her are every bit as vivid and compelling as those of his scholarly mentors.

To give an idea of the breadth of first-hand accounts written by artists and art lovers, I include three I’ve reviewed before. And I hope to add to the list before the season is finished.

Mentors: The Making of an Art Historian, by Francis M. Naumann (DoppelHouse Press, 2018)

The average student of art history can count himself lucky if he enjoys one or two great sources of inspiration to whet his curiosity and launch a career. Francis Naumann was extraordinarily blessed in studying with two of the greatest scholars of the 20th century, Leo Steinberg and John Rewald, who nourished his academic pursuits, while his friendship with the legendary ceramist Beatrice Wood (sometimes called the Mama of Dada) led to a long and fruitful collaboration for both.

Naumann hoped first to become an artist, an ambition that led him to do graduate work at the Art Institute of Chicago, where he indulged a continuing fascination with the works of Marcel Duchamp in a senior thesis that paid homage to the wily Frenchman’s obsession with chess. His graduate adviser, however, “thought it was strange that such an intelligent young man couldn’t make better art,” he recalls.

After moving to New York, a course at Hunter Collage with Steinberg changed the direction of his aspirations toward graduate work in art history. The author of Other Criteria and The Sexuality of Christ, among a shelf full of esteemed studies, was legendary as both a teacher and lecturer whose interests ranged from the masters of the Renaissance to Picasso to Jasper Johns. “Anyone who met Professor Steinberg realized almost instantly that he had an exceptionally favorable sense of his own intellect, and ego that—because of his staggering brilliance—was entirely justified, or at least seemed so to me.”

Equally gifted and temperamentally Steinberg’s polar opposite, John Rewald was the 20th century’s foremost expert on Impressionism, whose classes should cause any art lover to salivate: “They were not the usual lecture or seminar courses but rather informal discussions that took place in the living room of his art- and object-packed apartment on Park Avenue. Students sat in portable chairs that he set up for the sessions.” Those who wandered into other parts of the scholar’s lair might encounter works by Pissarro, Signac, Redon, Cézanne, Giacometti, André Masson, and Hans Bellmer. “I did not know exactly what he did to be in position to acquire those important works of art,” Naumann writes, “all I knew was that I wanted to do the same thing….” The student and his mentor eventually became close, largely because of the author’s fluency in Italian, and the two traveled through Italy and France, spending time at Rewald’s sumptuous villa in Menerbès.

Though steadfastly admiring and respectful toward his elders’ accomplishments, Naumann is by no means blind to their foibles as human beings and gets involved in some entertaining escapades, such as a tour of Times Square porn shops with Rewald and the birthday gift of a prostitute for Leo (who would have preferred the madam of the establishment). No slouch when it came to sexual high jinks, Beatrice Wood engaged a pair of lesbian lovers for Naumann’s amusement (he graciously declined).

Throughout these lively and affectionate reminiscences hovers the ghost of Duchamp, who was the subject of much of Naumann’s writing and the centerpiece of a splendid exhibition called “Making Mischief: DADA Invades New York” at the Whitney Museum in 1996. Such was the influence of his idol that Naumann eschewed serious relationships with women—in the belief that he was following Duchamp’s lead in romantic attachments—until he learned that the impresario of one of the most radical art movements of all time was just as susceptible to love as the next mortal.

Now in his 70s, Naumann was fortunate to have come of age in an era when art historians could claim a measure of celebrity almost the equal of top-tier artists (Robert Pincus-Witten and Robert Rosenblum were two other outstanding scholars in his orbit). I don’t know that the discipline still nurtures this kind of star power (Linda Nochlin had it too), but it is bracing to read about the brilliance and humanity of this generation of pioneers.

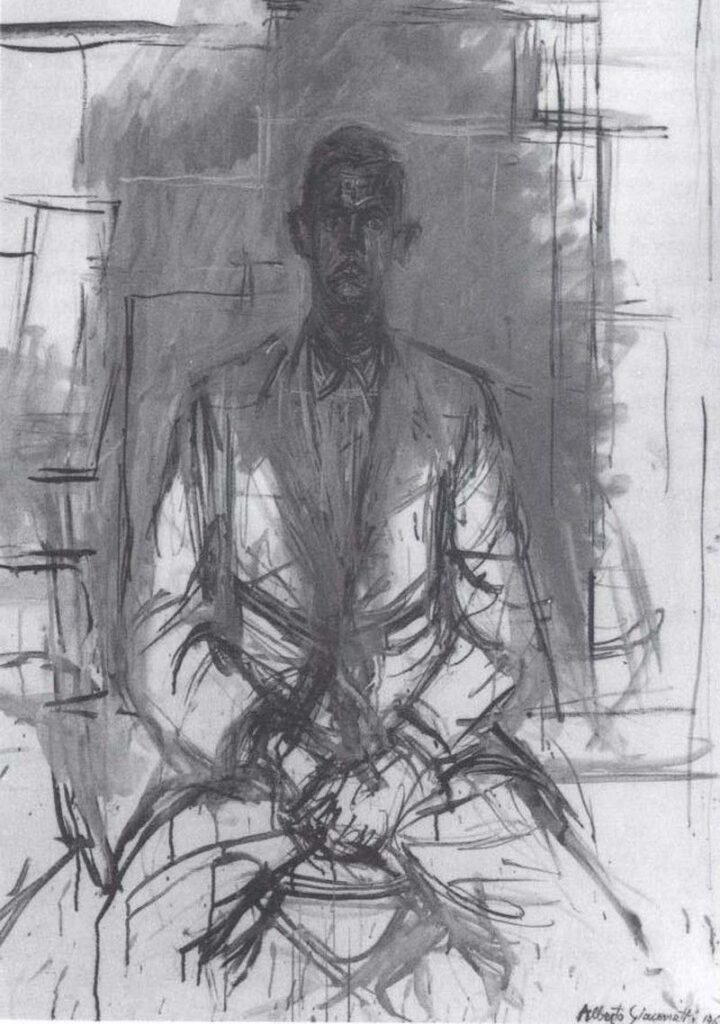

James Lord, A Giacometti Portrait, by James Lord (originally published by Doubleday in 1965, available on Amazon, at used book stores, or possibly in your local library)

In the early 1960s, an intrepid young American writer named James Lord bravely accepted Alberto Giacometti’s invitation to sit for a portrait by the maestro, who was by then an international celebrity almost on a par with Picasso. What was to be an afternoon’s exercise, “a quick portrait sketch on canvas” in Lord’s words, turned into 18 days of posing as Giacometti wrestled with self-doubt, despair, and an “aura of anxiety that surrounded our mutual work in progress.” Lord’s account includes the substance of many of their conversations—Giacometti’s reminiscences about escaping war-torn Paris, his asides about art and artists (especially Cézanne and a certain portrait by Jan van Eyck), and the occasionally deadpan exchanges between them. Example:

“Later, he said, ‘You look like an Egyptian sculpture, but more handsome.’

“’Why more handsome?’ I asked. ‘Because I’m alive?’

“No. Simply because you’re not an Egyptian sculpture, that’s all.’”

Lord surreptitiously took careful notes about the more than two weeks he spent posing and made photos of the work in progress, noting the “identification between the model and the artist, via the painting, which gradually seems to become an independent, autonomous entity served by them both, each in his own way and, oddly enough, equally.” Giacometti’s exasperation with his progress, his inability ever to get it right to his satisfaction, does verge on the comic at times, but it’s in no way close to the buffoonish, senescent character played by Geoffrey Rush in the 2017 movie Final Portrait.

Any artist who has ever struggled with doubts about the worth of his or her work—and who has not?—will find solace in Lord’s deft account, written more than 60 years ago and still as vivid as an encounter with one of Giacometti’s skeletal sculptures or searching portraits.

Marina Abramović: Walk Through Walls (Crown Archetype Books, 2016). In the course of her long and well-documented career, Marina Abramović has slammed her naked body into concrete walls, scrubbed bloody cow bones, lived for two weeks in the windows of a Chelsea gallery, walked the Great Wall of China, nearly suffocated inside a framework of fire, and most memorably sat immobile day after day in a kind of face-off with strangers at the Museum of Modern art for the ten weeks’ duration of her 2010 retrospective.

It’s possible her childhood in Yugoslavia, the daughter of distinguished war heroes who were indifferent or cruel to the young Marina, helped shape a predilection for self-abuse. “I was punished frequently, for the slightest infraction, and the punishments were almost always physical—hitting and slapping,” she writes. Her mother and aunt beat her “till she was black and blue.” For her 14th birthday, her father gave her a pistol, and she brought a schoolmate home to play a game of Russian roulette (the bullet landed in the spine of Dostoevsky’s The Idiot).

But don’t expect Abramović to do a lot of heavy soul searching as to why she does the things she does. Instead, this harrowing and occasionally funny account takes us on the artist’s journey to art-world mega-celebrity. You may get annoyed at the often breathless and unpolished prose (“time stopped as we stared into each other’s eyes”). You will need to withstand a fair amount of woo-woo talk about tarot cards and clairvoyants and kundalini life forces and gurus and monks. And you will undoubtedly be nauseated by the descriptions of some performance work. But for all that, Abramović has a flair for dramatic storytelling and has lived one hell of a life.

Sally Mann: Hold Still (Little, Brown and Company, 2015). Some may remember the huge controversy that attended the publication of Sally Mann’s photographs of her three children, in a collection called “Immediate Family,” in the early 1990s. In the photos themselves, of the kids naked and often striking make-believe adult poses, and in the profile presented in The New York Times Magazine, Mann came off as imperious and a bad mother, willing to sacrifice her children to her art. The reaction was swift and outraged: reams of letters to the editors, harsh assessments by critics, and assaults on the family, including at least one person who harassed them for years.

Two decades later, the photographer coolly assesses the reaction and her own response, but this book is far more than a photographer’s memoir of her subjects. Mann is a stylish and commanding writer who has sifted through a trove of family papers and old photos to excavate a Southern past more gothic than any imagined by Carson McCullers or William Faulkner. Generously illustrated, this is a story of troubled but gifted parents, memorable ancestors, long-suffering family retainers, clandestine affairs, and murder and suicide.

Most bracing of all is the way the artist writes about her vocation and what drives her. “Art is seldom the result of true genius,” she writes, “rather it is the product of hard work and skills learned and tenaciously practiced by regular people. In my case, I practice my skills despite repeated failures and self-doubt so profound it can masquerade outwardly as conceit. It’s not heroic in any way….I make bad picture after bad picture week after week until the relief comes: the good new picture that offers benediction.”

Top: Marina Abramović and her former partner Ulay in a performance piece from 1998

Ann, these are terrific books and wonderful reviews. I agree with you about the aliveness of memoir over biography. Your own “Rotten Romance” has to join the list as a published book soon.