Peri Schwartz’s affinity for the subjects that have preoccupied her for decades started when she was growing up in Far Rockaway, a seaside neighborhood in Queens, NY. She would set up objects to draw when her parents went out on a Saturday night so they could see she’d done something productive in their absence. “Even at that age I was making still lifes or interiors,” she says. She also took a figure-drawing class at night when she was in the sixth grade but felt bad the model had to take off her clothes. “I didn’t get it at that age that that’s what artists often do, they draw from the model.”

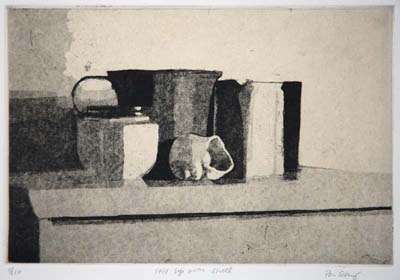

When it came time for college, Schwartz landed at the Boston University School of Fine Arts, where a traditional curriculum prevailed: “Figure drawing, anatomy, and tonal painting were the background,” Schwartz remembers. In particular, a teacher named Robert D’Arista taught students about the Golden Triangle and how to use those proportions in their compositions. “He would come into class with a bagful of objects and set up the most interesting still lifes,” she says. “We could only paint with black and Venetian red and no curves—only verticals, horizontals, and forty-five-degree angles.”

Schwartz married her boyfriend, a law student, right out of college, a path that didn’t sit well with some of her professors when she was attending graduate school at Queens College. She reports being treated with less respect because she had chosen a “more traditional life.” But nonetheless as soon as she got her master’s degree, she rented a studio on the top floor of a brownstone in Park Slope. (She now lives in New Rochelle, where she’s been in the same studio for 18 years, the only artist in a building full of accountants and lawyers).

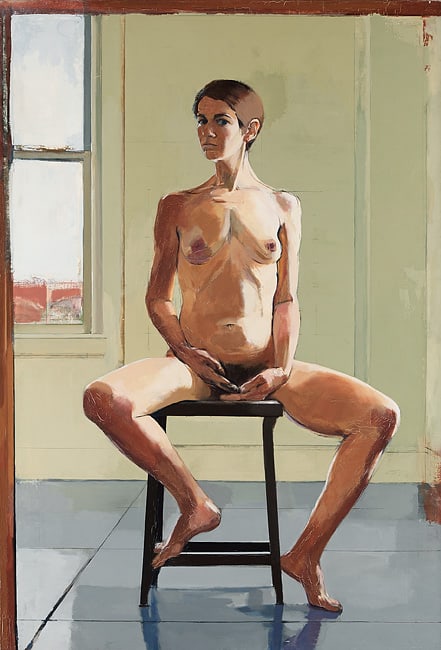

For many years, Schwartz made self-portraits a regular part of her practice, including one forthright nude whose sidelong gaze seems to challenge the viewer with the unanswerable question: “So what are you looking at?” When the art writer Deven Golden, now a contributor to artcritical.com, saw some of her studio self-portraits in the early 1990s, he remarked, “It looks to me like what you really want to do is draw your studio.”

She describes her work around that time as “dark still lifes, more Morandi-like than what I’m doing now, and what he said made a lot of sense. I got to the point where I was much more interested in the objects in my studio.”

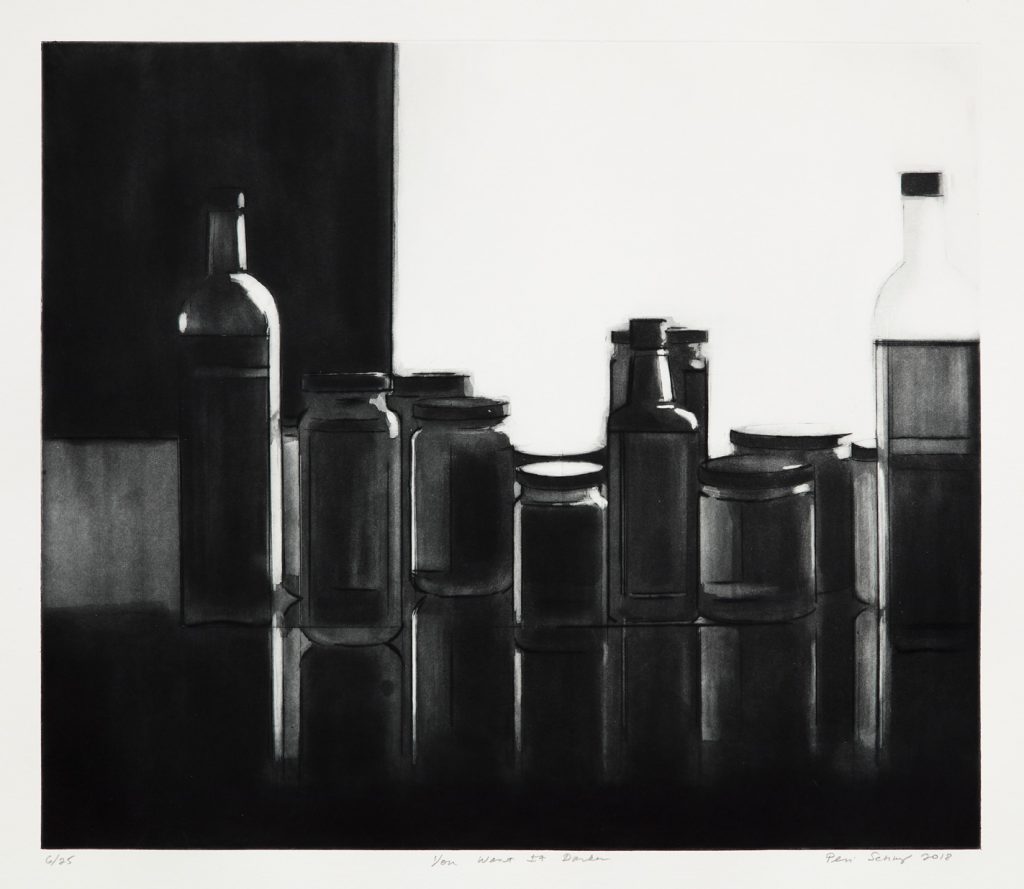

Schwartz did not entirely abandon self-portraits, but her primary subjects, since about the turn of the millennium, have been bottles and jars and views of the studio, occasionally with a glimpse outside the window to the buildings and sky beyond. Sometimes, as in Studio XXXII (2011), the interiors approach a level of near-abstraction, a Hofmann-like mash-up of brightly hued rectangles that seem on a barely restrained collision course.

The difference between earlier and later studios is that earlier compositions “looked more like an artist’s studio, with canvases leaning against the walls and stools with books piled on them,” she told an interviewer for the online publication Painting Perceptions. “In the more recent studio paintings, the books are shapes of color with no bindings to indicate they are books. The canvasses have now been replaced with wooden boards that I paint with sample colors from the hardware store. I’m still captivated by the color I get from liquids in bottles and jars and how they are reflected on a glass tabletop. The grid that I have been using in my work for over thirty years is as important as ever.”

It can take Schwartz a week or two to set up a composition. And then she makes a drawing, most recently on Mylar, working with a combination of charcoal and Conté crayon, which produces striking dark areas and erasures that look bright because of Mylar’s translucency. “It may be three to four weeks before I actually order a canvas,” she says.

She has deviated from her preferred subject matter only a couple of times in the past three decades—for a series of monotype portraits around 2009 and earlier, in 1989-90, when she took a break from self-portraits to draw her young son’s wooden blocks. “After I tired of their hardness I picked up a sweatshirt and wrapped the blocks,” she told Painting Perceptions. “I had worn sweatshirts in many of my self-portraits and loved the way the fabric could be molded. The idea of wrapping objects in sweatshirts developed to the point that I was making complex sculptures and then drawing them. Unlike the self-portraits or the studio paintings, after two years I had exhausted the subject.”

Schwartz also takes breaks to make prints with master printer Gregory Burnett, who also works with Glenn Ligon and Kara Walker. “I can’t emphasize how important it is to do prints, especially for young artists,” she says. “So many things feed your working process. Richard Diebenkorn talked about this—printmaking is like speaking French, you have to use a different part of your brain. The brushstroke on a canvas is so different in color and intensity from the marks in a print.”

Schwartz’s single-minded dedication to a limited range of subjects has in no way limited her audience. Her works are in numerous public and private collections, and through March 29th, “Peri Schwartz: An Exhibition of Paintings, Drawings, and Prints” will be at the Flippo Gallery of Randolph-Macon College in Ashland, VA. And she recently sold one of her self-portraits to the Minneapolis Museum of Art. “I feel very happy in terms of work,” she says simply.

Ann Landi

Top: Studio XXXII (2011), oil on canvas, 44 by 40 inches

I love the comment about printmaking is like learning French, you use another part of your brain!

While Peri Schwartz’s self-portrait glance is beautifully evocative; her erectness, cupped hands and imminent lower limbs make for a very stunning portrayal.

The work seems so intuitive and fresh, a real contrast to the setting up. Beautiful work!

Like your work.