Paul O’Connor first fell in love with photography when he joined the navy at the tender age of 17. “My dad gave me a camera, an Olympus, and I started taking pictures—especially of clouds out at sea,” he recalls. Those big billowing skies would prove equally entrancing when he moved to Taos, NM, many years later, but in the interim there was much to learn about the camera.

After three years in the navy, O’Connor studied first at Santa Monica City College and then landed at Pepperdine University in Malibu, CA. He was working toward a degree in economics with the goal of becoming a lawyer, like his father, but in his last term took a course in beginning photography, which he remembers as “the toughest B I ever got.”

It was in that class that he made a portrait of himself with his dead cat (featured on the site in a post about self-portraits); another assignment asked students to make an “environmental portrait,” recording a subject in his or her typical surroundings. O’Connor captured Ronald Davis in his studio; by then (1987) the artist was a celebrity of the California art scene, renowned for huge, colorful, eye-bending works in polyester resin.

“That set up the whole notion of doing portraits of artists,” O’Connor recalls. “Ron lent me his dad’s four-by-five Busch-Pressman camera, and I started fooling around with that.” His efforts also helped him land a scholarship to the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, CA, where he met his wife, Tizia, a friend of one of the models he was photographing.

é

é

On their honeymoon, they went camping in the deserts of southern California and Arizona. Tizia was reading a biography of Georgia O’Keeffe, which of course mentioned her time in northern New Mexico, where she settled first in Taos and later in Abiqui. The couple, he says, “rented a place in Taos within three days, and then drove back to Malibu and packed up.”

For a photographer with an interest in portraits or artists, Taos had no shortage of subjects: a wave of emigrés from southern California included Ken Price, Ron Cooper, Dennis Hopper, and Larry Bell, along with notables from other parts of the country, like Agnes Martin and Bea Mandelman. Not to mention the scores of lesser-knowns who still make the town one of the great art meccas of the Southwest.

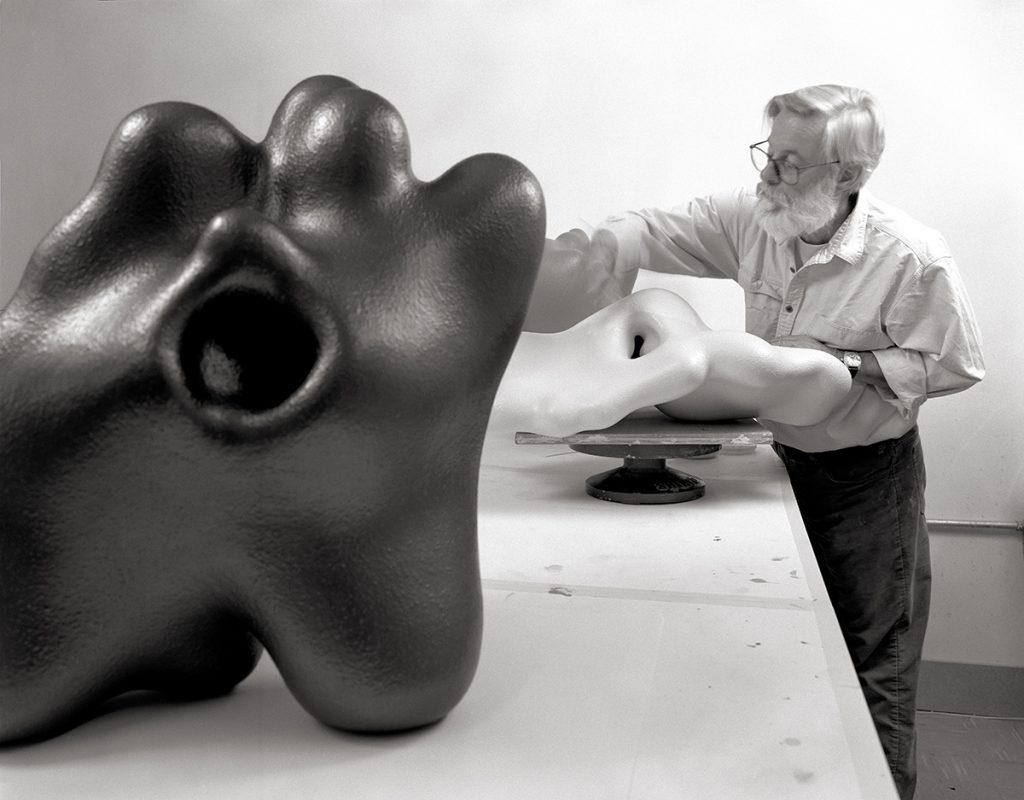

O’Connor had his first show of portraits in 1991, and then worked as a studio assistant to Davis, who had moved to Taos to pursue sculpture in the early 1990s. In 1996, though, the artist and his wife rented their house, picked up stakes, and decided to move to France out of a desire to raise their daughter in the French school system (Tizia, a specialist in Ayurvedic medicine, hails from a little beach town near Biarritz).

They bought a 1927 inland barge in Holland and navigated it down the rivers and canals to Toulouse. In addition to teaching English and working in construction, O’Connor began making small sculptures from pieces of scrap metal and wood. “I always knew they were highly derivative—essentially they were Ron Davis knock-offs,” he says. “I never showed them, but I got obsessed with making hanging constructions and reliefs, even if I didn’t feel they were really my own.”

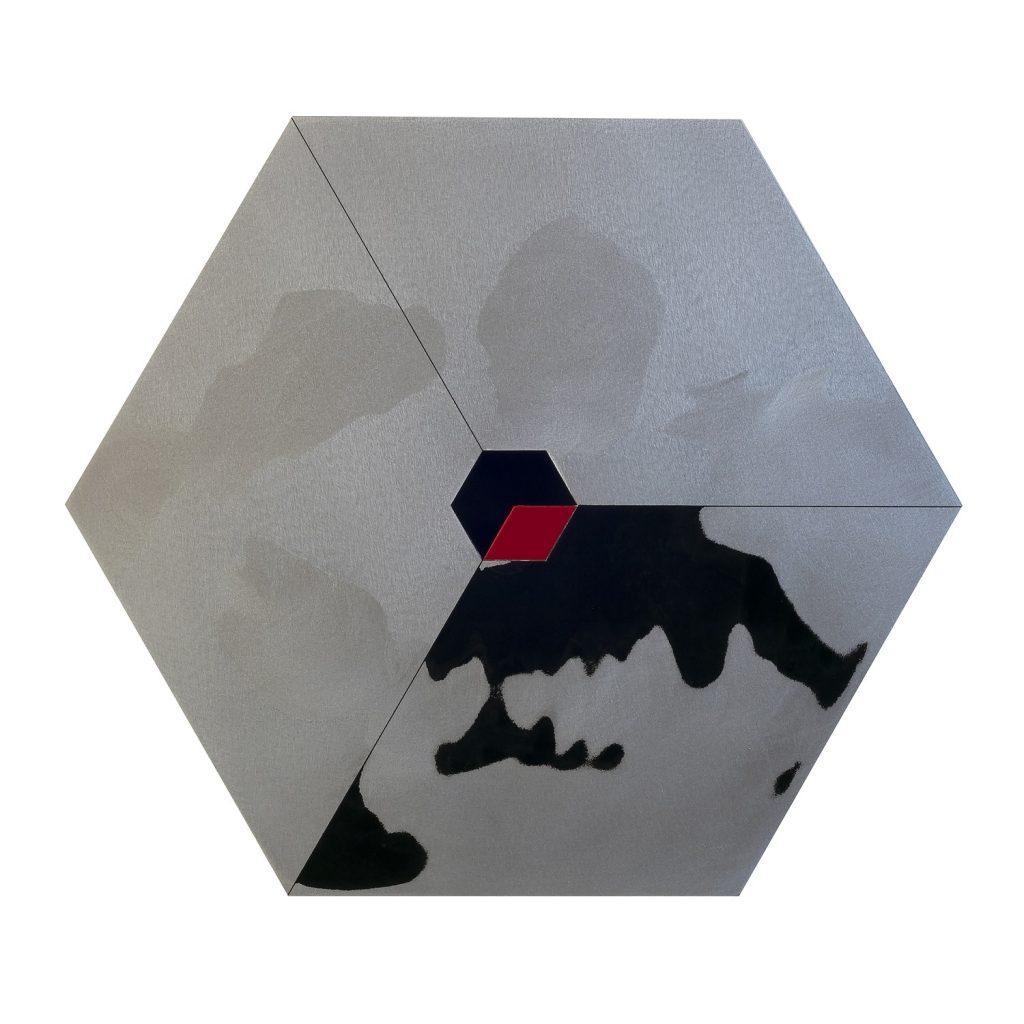

The O’Connors spent eight years in France, and then in 2012, after the artist published a volume called Taos Portraits, he felt one chapter had closed and a new one was beginning. “I allowed myself to go head-long, full-time into sculpture,” he says. “I gave myself an assignment to get away from the influence of Davis, and that assignment was to work within the shape of a square and a hexagon, using no perspective.”

His own vision of what a sculpture could be all started with a hole. “I was working on wooden pieces, and there was a knot that fell out midway through putting one together,” he recalls. “It reminded me of the holes in Ken Price’s sculptures. That became an important element for me, a meditative space. It keyed into the notion of the origins of all things—that primordial space. I regularized that void by moving it to the center of all future pieces and made it either a round or hexagonal shape.”

He also added rulers—a memento of his years of building and navigation—and worked in many kinds of metals and wood. As this writer noted in a review of his show at Bareiss Gallery in Taos in 2016, “O’Connor’s delight in his materials is infectious. He’s found unusual woods—like purple heart and leopard wood—and showcased them almost with a kind of reverence. Stained plywood comes magically alive with a grainy sensuality one would never have expected from this humble stuff. Brass gets polished to a high gloss or left at a quiet smolder. Rusted steel, weathered in the elements, takes on unexpected jazzy patterns. And when aluminum meets Bondo, the upshot is a magical surface suggestive of rain drizzling across a window pane.”

Of late, O’Connor has been making larger works, sometimes incorporating auto-body paint in gleaming black and red. And the sculpture are gradually acquiring a larger audience in shows in New York, at the Miami Basel art fair, and in Zurich, where he is represented by Laurent Marthaler Contemporary and is part of a show there through March 31 called “Fields of Precious Emptiness.”.

He’s also still at work on photographic portraits of artists and will have an exhibition of these in June at the Encore Gallery of the Taos Center for the arts.

That the artist can move easily between different mediums, between photography and sculpture, is probably testimony to a lifetime of learning different skills, especially building and understanding the camera. His sculptures are carefully wrought, even the backs, with their surfaces made up of several layers of marine-grade plywood that have been carefully stacked and glued. The photos also rely on a craftsman’s expertise, both for the careful posing and the knowledge of how to coax depth and variation from a black-and-white image. And both, in different ways, depend on the eye—both the literal central focus of the sculptures and the metaphoric eye of the dedicated lensman.

Ann Landi

This article delightfully reveals a special artist. Having been at the 2016 inaugural sculpture show I am piqued to see the expansion of Paul’s current work.

Beartifully written and expressed of Paul , his life and his work. m. oliver

This is an awesome article! Love you Paul.

An exciting diversity of work. Onward Paul O’Connor!