The Abstract Expressionist generation has gone down in history as mostly male and exceedingly macho. Jackson Pollock boozing it up and brawling at the Cedar Bar. Willem de Kooning slashing his way through that still-disturbing “Woman” series. Franz Kline bravely paring back his imagery to a few bold black strokes. Museum shows, biographies and tomes on modern art still celebrate those pioneers of a distinctly American movement, launched in the 1940s and in full flower by the middle of the next decade.

And yet there was a significant cohort of women painters who came into their own at the same time and were by and large accepted as equals in the scruffy downtown milieu that nurtured them all. Recent surveys at the Denver Art Museum and the Museum of Modern Art in New York have paid homage to their accomplishments, and now comes Mary Gabriel’s sweeping and deliciously readable “Ninth Street Women.” Ms. Gabriel, the biographer of characters as diverse as the suffragette Victoria Woodhull and Karl and Jenny Marx, focuses on five painters: Elaine de Kooning, Lee Krasner, Joan Mitchell, Grace Hartigan and Helen Frankenthaler. These artists are material enough for 700-plus pages, but the author also weaves a vivid tapestry of bohemian life in New York as that city was supplanting Paris as the capital of the art world.

Krasner and de Kooning were the senior members of the group, both Brooklyn-born and determined to be artists at a time when there were few female role models and little encouragement from families and teachers. Both also married future stars of AbEx—Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning—and endured years of struggle furthering their husbands’ careers, often at the cost of their own. Krasner fought the bigger battle, keeping Pollock on track and sober, while the de Koonings, though breezy about each other’s infidelity (at least until Elaine traveled to Provincetown with another man and Bill had a child by another woman), retained a lifelong respect and affection for each other. Both couples quarreled viciously, but it seemed almost the norm in a group that favored hard drinking, volatile meetings and physical scuffles everywhere—at home and in bars, at gallery openings and during an endless cycle of parties.

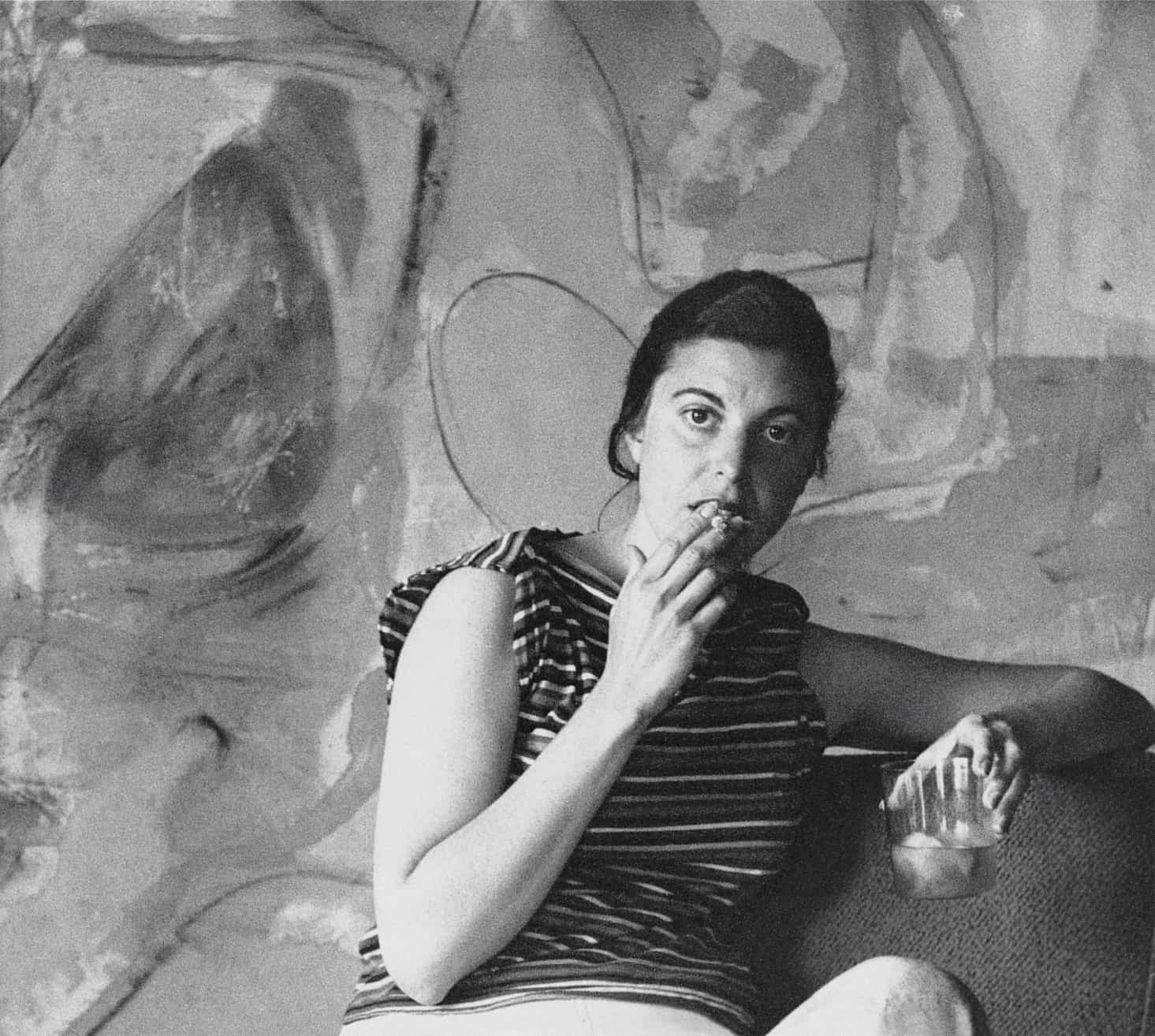

A striking beauty with a dancer’s figure, Elaine rapidly became a magnet on the scene. She was only 20 when, in 1938, she met Bill de Kooning, who was first her teacher and mentor and soon her lover. “As a man, he loved her vibrancy, wit, social grace, but most especially her thick red hair and, yes, her long American legs,” Ms. Gabriel writes. “Bill was also extremely proud of her. He had become the envy of his friends, who congratulated him on his ‘cute trick.’ ” But she was no mere arm candy and grew into a dedicated artist and teacher, even as she worked hard to promote her husband’s art. Also a writer, she helped put ArtNews in the forefront of contemporary-art journals, working closely with editor Tom Hess to craft an intimate, conversational tone that explained the artists to one another and to the world at large, which would slowly take note of the revolution under way in New York.

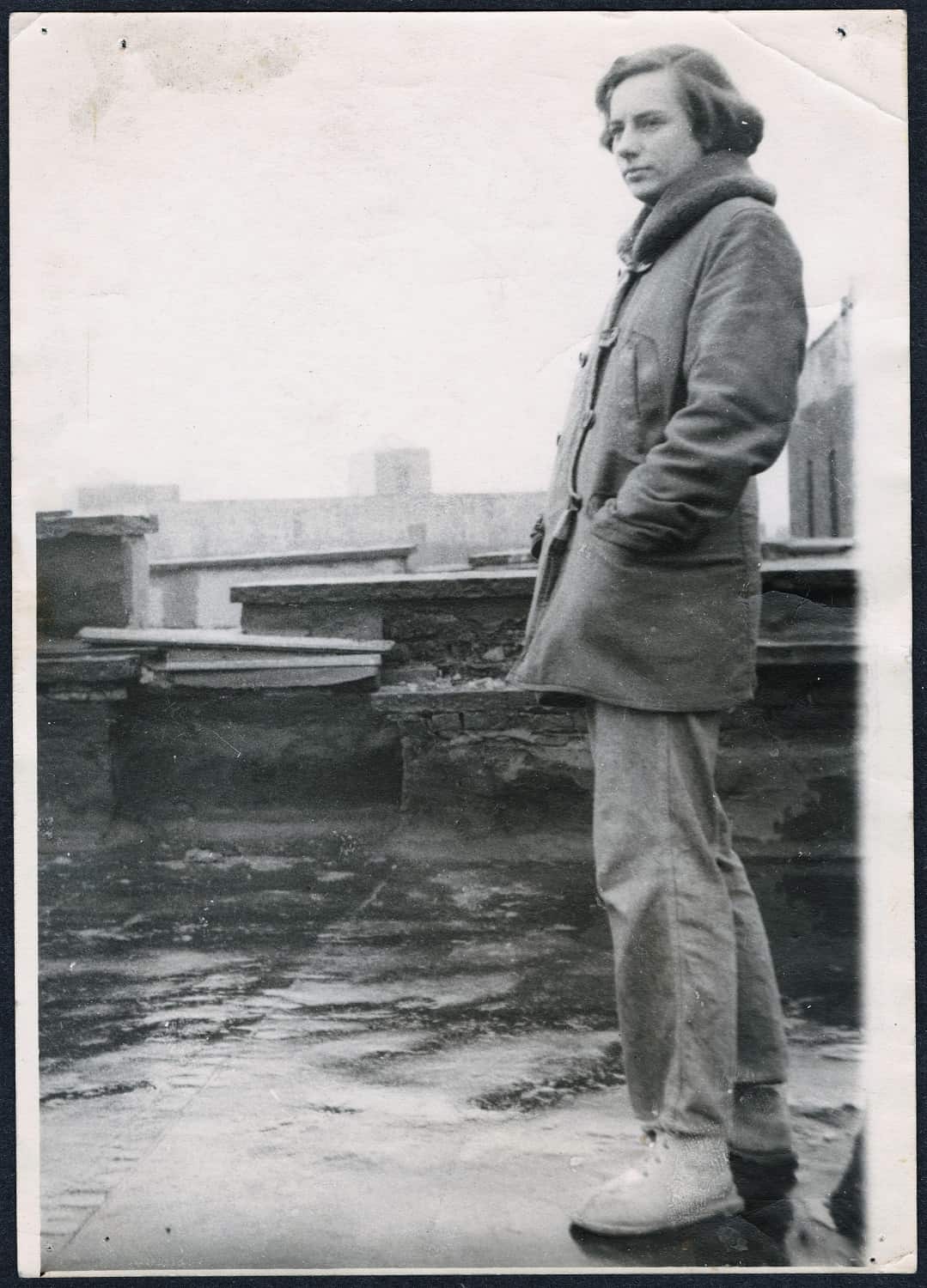

Joan Mitchell and Helen Frankenthaler, nearly a decade younger than Elaine, both came from backgrounds of wealth and privilege, but there the resemblance ends. The daughter of a prominent Chicago doctor and an editor of Poetry magazine, Mitchell enjoyed scant encouragement from her family and rebelled early, wearing men’s shirts and jeans (under a fur coat) and leaving home for good at the age of 20 to travel to Mexico and then New York and Paris. Frankenthaler’s family of Jewish intellectuals—her father was a New York State Supreme Court Judge—was more accommodating of a talented daughter. She studied at the progressive Dalton School and Bennington College and would make her mark early, inventing at age 23 a new way of working thinned pigments directly onto unprimed canvas, a technique that would spawn what came to be known as Color Field painting. Of Ms. Gabriel’s subjects, she enjoyed perhaps the most stable romantic relationship, a 13-year marriage to Robert Motherwell, after a stormy five-year liaison with the influential critic Clement Greenberg.

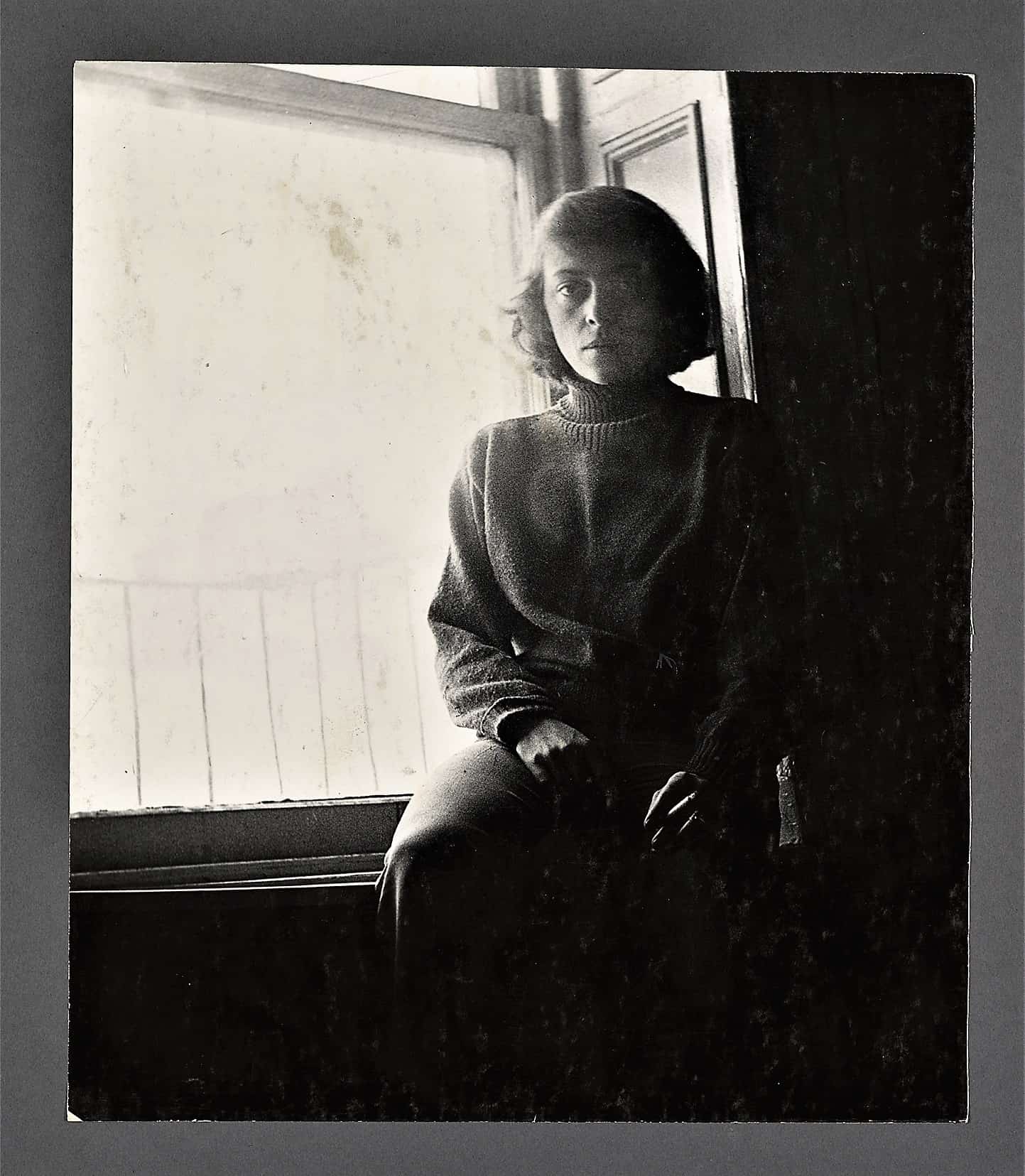

Grace Hartigan had undoubtedly the roughest and most unconventional path of all. She married at 19 and landed in California, where she soon had a son. After war broke out, she went to work in an aeronautics plant back East and later took a drafting job to support an artist lover who was twice her age. Her introduction to Pollock’s work in his first show at Betty Parsons’s gallery in 1948 changed her life as a painter and a woman. Eventually disentangled from both lover and husband, she handed over her son to his grandparents to raise and plunged into the frenetic life of the downtown avant-garde. During the heyday of the movement, she became a glamorous icon, involved with many men but most in love (though chastely) with the poet Frank O’Hara.

Seated from left: Elaine de Kooning, Lee Krasner, Willem de Kooning, and Jackson Pollock at the Museum of Modern Art, ca. 1950

“Ninth Street Women” is like a great, sprawling Russian novel, filled with memorable characters and sharply etched scenes. It’s no mean feat to breathe life into five very different and very brave women, none of whom gave a whit about conventional mores. But Ms. Gabriel fleshes out her portraits with intimate details, astute analyses of the art and good old-fashioned storytelling. We read of times so desperate that Bill de Kooning made tomato “soup” from ketchup and water, or parties so raucous and heated that Greenberg once knocked Frankenthaler down with a slap and then brawled with her date. An end-of-an-era bash in the Hamptons in the summer of 1958, featuring a dance floor on pontoons and a special barge to carry jazz musicians (among them, artist Larry Rivers), sounds like more fun than anything imagined by F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Anyone with even a small familiarity with the period will enjoy the element of built-in suspense: When will Helen finally break off with the arrogant and insensitive Greenberg, who failed to acknowledge her important breakthrough and disparaged a group of women artists to their faces? Will the stormy de Koonings ever divorce? How will they all respond when the increasingly sodden and boorish Pollock finally plows his car into a tree, killing both himself and a friend of his mistress? And how will these artists, who had developed in the most unpromising of circumstances, handle the world-wide fame and celebrity that came their way in their 40s and 50s? (Short answer: not well.)

The supporting cast of characters—including Rivers, dealers John Bernard Myers and Leo Castelli, curator Dorothy Miller, collector Peggy Guggenheim and Grove Press publisher Barney Rosset—also get their due. Ms. Gabriel is equally adept at sketching out the temper of the times: the end of the Great Depression and World War II, the dawn of the Cold War and the paranoia of the McCarthy era, and the sexist attitudes that prevailed toward female artists. Near the close of the book, she describes the arrival on the scene of fresh young artists like Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, whose work signaled the arrival of a new and cooler chapter in the story of American art.

Ann Landi

Top: Willem de Kooning and Elaine de Kooning, 1944

Republished from The Wall Street Journal, September 20, 2018

Ann, a wonderfully written review and I look forward to reading the book. In spite of how distraught the immediate times are I look forward to reading about the nyc scene that also captured my own parents.

I have several of these women artists played by intelligent, serious & skillful women artists in their own right in my Indie feature “PollockSquared”. Mostly shot in the early 2000’s but some added a few years ago. My Lee Krasner has a starring role equal to Pollock & we did some shooting at her Brooklyn Museum retrospective show in 1999 besides many other lications in luding the Pollock / Krasner House & Study Center. I once spent the day with Elaine de Kooning in 1981 who visited my SoHo studio at 74 Grand Street resulting in her creating a print of our older artist friend & my NYC mentor, Aristodimos Kaldis a long time intimate friend of Willem. I met Clement Greenberg in 1973 shortly after I moved here for the Whitney Program. We hit it off & exchanged some letters & a few year later Clem encouraged me to take on the Whitney Biennials in my Whitney Counterweight exhibitions held throughout SoHo beginnng in 1997. I earlier with my ex had met Joan Mitchell in Madrid & there ensued a dangerous adventure. My film has never been formally released though had several partial screenings, once at MoMA in a solo evening given me in the Titus theater. Leo Castelli & I hit it off because of Andy i knew & Leo allowed my videoing on.my own dime most all his key show openings at 420 West Broadway in SoHo in the 90’s never once reproaching me. I am once again taking on the final edit after several times being crushed by finances & hope to finally release it in a few months. There are several famous real art critics in mine & of course one playing Clem.

Rabinovich’s ‘Pollock Squared’ movie is indeed stunning, when Lee and Ruth finally get together for a confab, Krasner and Kligman are both titans of the times, we knew, we in this lark of Bill’s filming in the 90s to the 00s in downtown NYC. Our rapprochement was a handsomer conclusion to the bitterness. As Pollock, i held up two middle fingers in silence, to explain to Clem Greenberg how much i appreciated his lame support, this shot in the Cedar Tavern on University Place. And don’t forget that Ruth moved in with Pollock and later De Kooning once the wives were a continent away. Gracefully, if not discretely.

Keep me posted on the movie!

Who knew what influence these women had in their own era? I had been writing reviews of these amazing female artists without knowing their stories. This book, I will relish! Thank you for the wonderful review, Ann.

Sorryv Made a typo, the first whitneyvcounterweight I mentioned was in 1977 not 1997.

I can’t wait to read this book! Your review makes it sound so intriguing. The film “Pollack Squared” sounds interesting as well.

Can hardly wait to read the book and listen to podcast of author, Mary Gabriel.

And the book appears at such an important time for women. Thank you Ann.

These women look much more interesting than the macho pretentious AE artists that surrounded them. I guess it is true that life is not fair. I say this as a guy (which I am)…

Sorry for the earlier comment ruined by automatic typo correction.