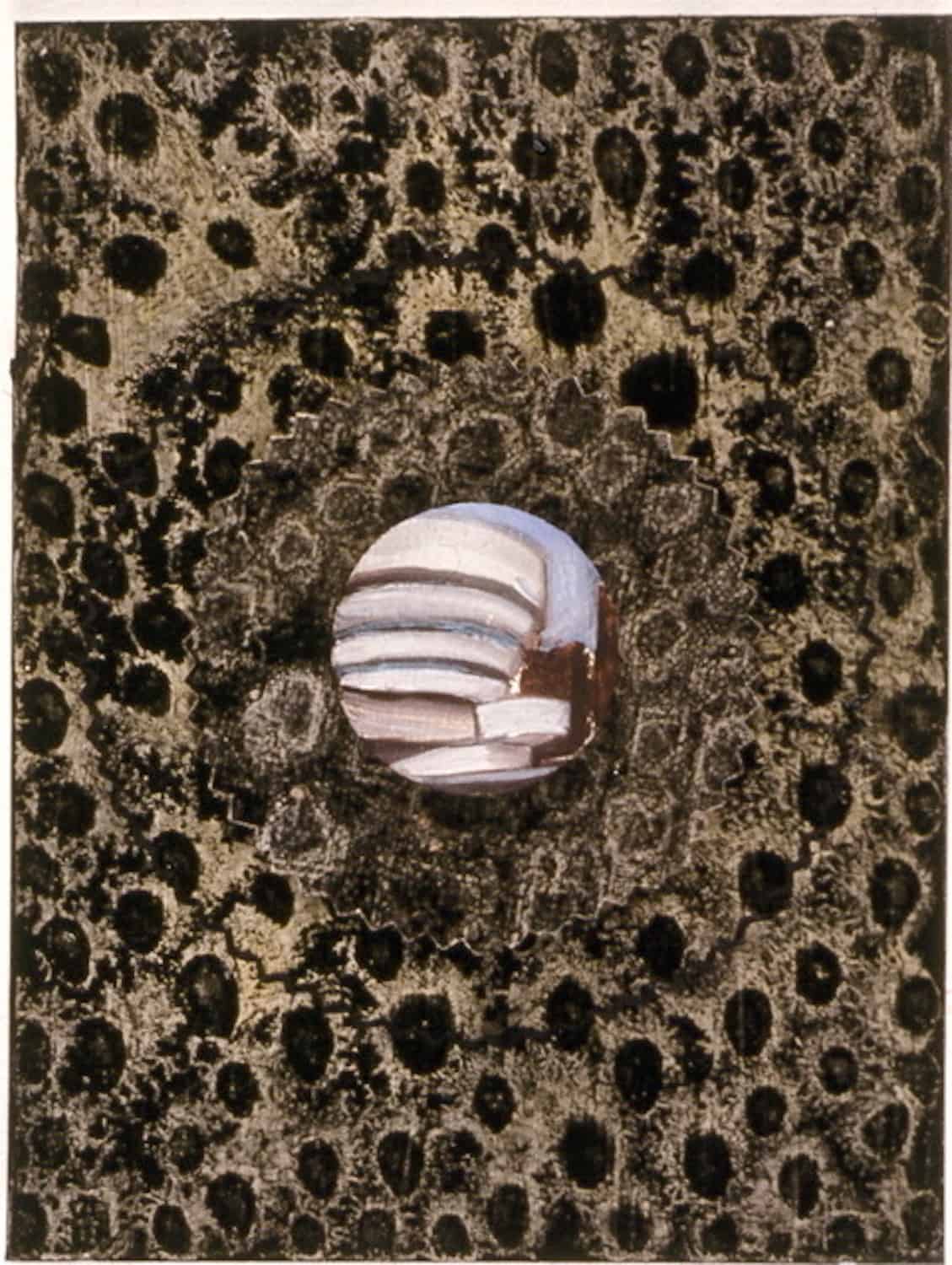

From the “Oracles” series (1995-96), The Guggenheim, oil on paper and linen-covered button. 6.5 by 4.75 by 1.6 inches in diameter

Two preoccupations have remained constant in the art of Mila Dau as it has unfolded in the last 25 years: a fascination with people and a love of architectural spaces, specifically the interiors of museums, here and in Europe. It seems inevitable that the two were bound to collide, so that in her latest series, “Cutouts in Context,” we see figures, sometimes detachable and affixed with a string to the painting’s surface, doing what contemporary visitors to museums often do: they take photos, gaze absently into space, or occasionally make sketches. As Dau notes on her website, “The art seems to scream for attention as viewers distractedly consult their phones or walk past the scene into another dimension beyond the painting….I did not ask these people to take over when I added figures to the museum interiors, but I after I had, they compelled me to tell both their stories and mine.”

Dau’s paintings are bound to recall Thomas Struth’s massive C-prints of people looking at art in museums, but the experiences she presents are more candid and intimate (indeed one of her favorite museumgoers is her husband, Winnie Strathmann) than the panoramic dramas of the German photographer, some of which have been carefully staged. Realized in watercolor or oil, Dau’s works retain the painterly seductions of those mediums, but they nonetheless echo the question critic Michael Kimmelman asked in a 2007 review of Struth’s photos: “What are we looking for in a museum? We go to find truth in pictures, and we end up reading one another’s faces.”

Dau arrived at her present moment by way of a roundabout route that took her first through rigorous courses in architecture and design. Her parents emigrated from Rome to Montreal because her father, an engineer, found more opportunities for work in Canada. When she was 18, her parents sent her back to Rome “because I had a ‘quote unquote’ identity crisis,” she says, adding wryly, “I mean, who doesn’t have an identity crisis as a teenager?” At that point, she says, “the only world where I felt at home was in Italy.” In Rome she connected with the artist Maria Lai, a friend of the family whose work became renowned for incorporating thread and textiles. Like Dau’s father, Lai was born in Sardinia and she was a friend of the family who took the young artist under her wing and into her household for four years.

“What really influenced me about Maria is that she encouraged me to study architecture, not to go to the academy to study art,” Dau recalls. “I never had the idea that I wanted to be an architect but what I’ve retained is a love architecture, and of the assemblage of different elements.”

By the late 1980s, Dau was having shows in Rome, which were sufficiently accomplished to earn the notice of newspapers like La Repubblica. Her work at the time was focused on the art and architecture of Antiquity, examples of which abound in Rome. She was also instinctively striving to reconnect with her ancestry and to celebrate the beauty surviving destruction and time. But in 1991, she moved to New York in “search of greater opportunities for women artists and for the energy of a culture of the new.”

She landed in the East Village in a period before gentrification took over, when it was still affordable, and spent some time “trying to find what it was I really wanted to pursue as a woman artist,” she says. “I got this job, I got that job, I had life and work experiences that didn’t work out.” Among other gigs, she worked as a secretary, a foreign correspondent, and on projects for printmaker Bob Blackburn and sculptor Ursula von Rydingsvard. But by the mid-1990s, she had begun to find her way as an artist with a series of small works that featured structures from the classical world juxtaposed with the exteriors of contemporary art museums, all painted on linen-covered buttons. “If nothing else, these tiny tondos…are proof of how much contemporary architects owe to ancient Greece and Rome,” noted critic Raphael Rubenstein. “But Dau’s scenes, evoked with a sensual touch very unlike the cramped precision of most miniatures, are much more than history lessons.” Framed by blotchy abstract borders, they hint at the enigmatic nature of much of her future work.

A few years later, Dau turned to more-or-less straightforward portraiture in a series of likenesses of her art-world colleagues, including up-and-comers like Ghada Amer and Lorna Simpson and more established figures like Carolee Schneemann and Vito Acconci. Each sitting lasted only an hour and each is painted in full-frontal close-up. It was, noted Kathleen Goncharov, a logical step in moving “from the containers of art to its makers.”

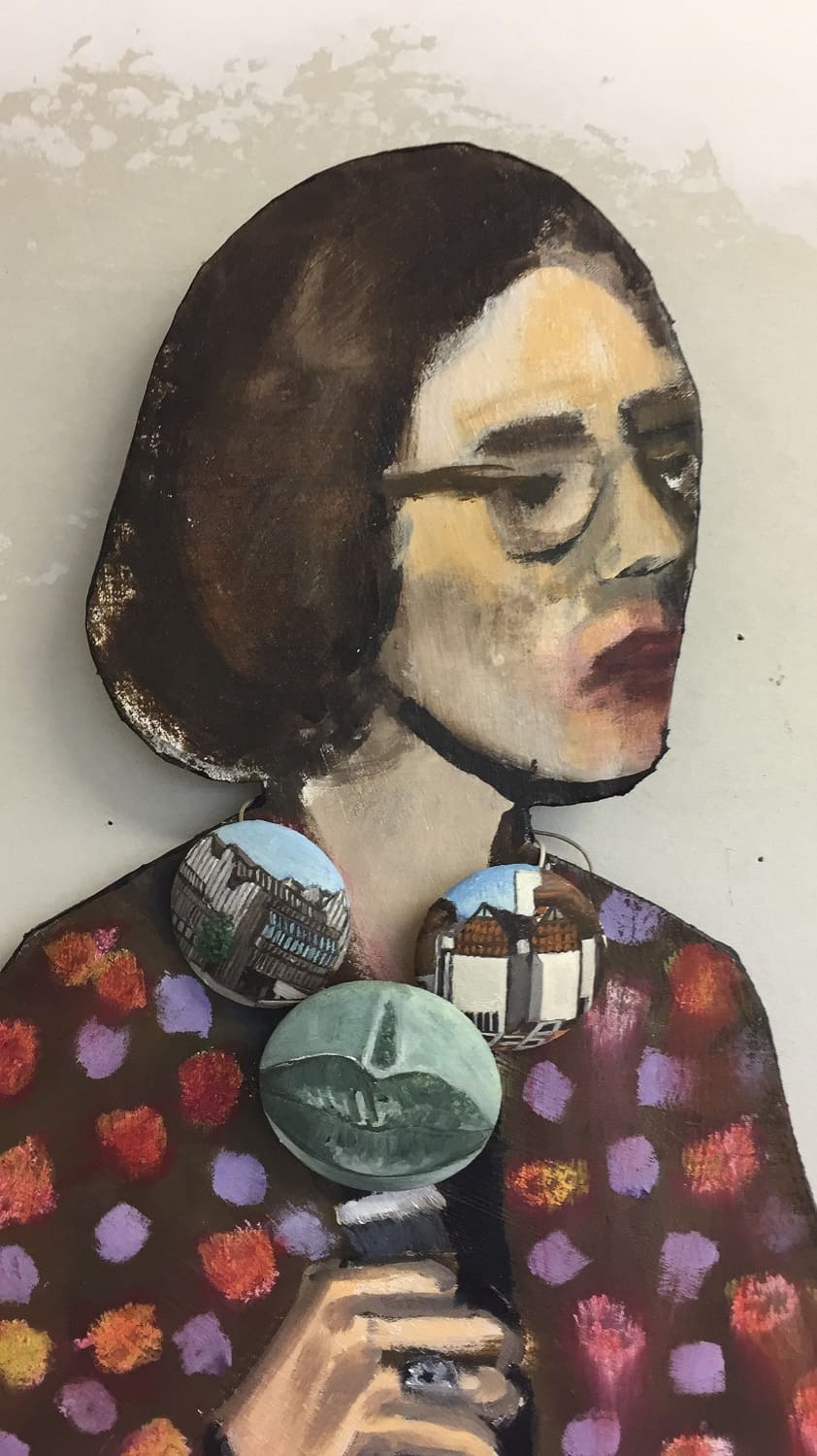

Connecting the Dots (2018), oil on linen (30 by 20 inches) and cutout on foamcoare (40 by 11 inches)

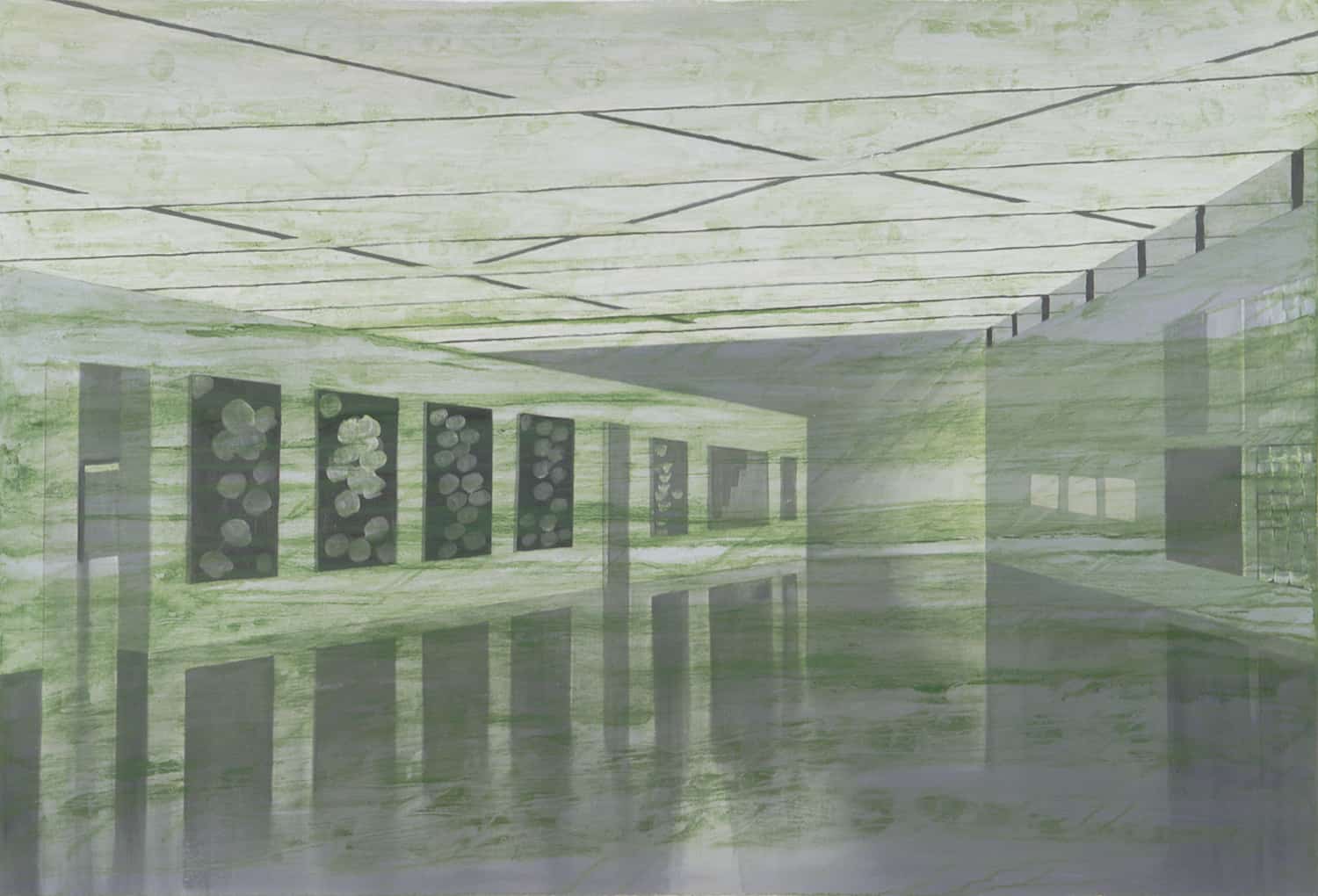

Her next series took her back to architecture, in a group of haunting visions of the vacant interiors of contemporary art museums. “I found myself noticing how the space around the art complemented and, at times, overpowered it,” she told another interviewer. “Some of these spaces were simply stealing the show.” Superimposed onto the barebones of the interiors are monochromatic layers of textured paint, some looking like lacy veils, others like a scrim of water, as though the museum were in danger of flooding. These are ambiguous statements, though Dau mentions that they are “pristine Euclidean geometry being invaded by the chaos of the paint. After that came the realization of the emptiness of the spaces.”

Betwee 2010 and 2013, the artist turned to making cutouts of figures—sometimes solo and sometimes clustered in a group—based on photos she surreptitiously took of people visiting museums. In her most recent works, she writes on her website, “the process of making the work begins with a ‘real’ museum setting and ‘real’ figures caught in the moment of looking at art but it can also veer away from the photos upon which the paintings are based. The cutout figures can be combined with or detached from the museum context from which they came. I realized that the figures interacting with each other and with the spaces around them created other ‘realities.’ This was an opportunity for me to tell stories with spaces and figures simply by playing with the combinations and permutations of painted backgrounds and painted cutout figures.”

It all seems part of an ongoing process in which Dau as an artist is tackling some of the issues that have concerned critics of the contemporary art museum for the past couple of decades. What happens when the architecture overwhelms the art? In an era of relentless documentation of the museum-going experience on smartphones, who is paying attention to the collections and carefully curated shows? And is that experience primarily aesthetic or is it social?

Perhaps Dau, in her beguiling portrayals of people in search of artistic uplift (and often finding only other people), is getting close to some answers.

Ann Landi

Top: Crossing the Threshold (2017), oil on linen (48 by 56 inches), cutout on foamcore (40 by 16 inches)

… brava e intensa mila,

storie intime e pubbliche,

pitture domestiche che fanno compagnia al cuore

e al respiro …

Thanks for this article about Mila Dau’s beautiful and thought provoking work!

Un bellissima passione artistica fuori dagli ismi e dalle convenzioni. Formidabili visioni : grazie Mila

Wonderful article, wonderful artwork

. Thanks for inspiring me yet again Ann Landi with the work and story of Mila Dau. I wasn’t familiar with her, another instance when Vasari21 lifts me out of my own world and into another artist’s. The high point of my week!