Adventures in self-portraiture

Self-portraiture enjoys a long and illustrious lineage, probably reaching its peak in Western art with Rembrandt, who not only reveled in chronicling his changing fortunes—from ambitious youth to successful dandy to impoverished world-weary old man—but used his own features to explore different human emotions, like anger and surprise. The appeal of the genre to artists of previous eras is obvious: where could you find a better and cheaper model for a face, features, and figure than one’s own self? And who knows the subject better than the artist? More recent times have introduced elements of irony and mockery (Duchamp’s portrayals of himself as Rrose Sélavy; Rauschenberg’s likeness as a thumbprint with initials), but the self-portrait has never really died.

Nonetheless, not having seen a lot of self-portraiture among contemporary artists, I was somewhat surprised when I put out the call among Vasari21 members. More than two dozen responses rolled in, enough that I’ll present this report in two or three parts. The variety is astonishing: from tender realism to comic self-regard to full-blown abstraction.

Herewith Part One of “Me, Myself, and I,” the images accompanied by the artists’ interpretations and motives.

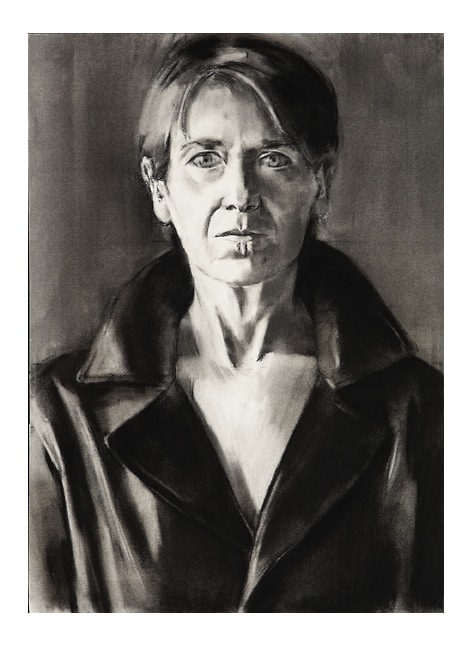

Peri Schwartz: Self-Portrait (2003), charcoal, 23 by 16 inches. At the time I was drawing self-portraits, I was studying and copying the portraits of the Old Masters. It seemed the only way I had enough time to work on a drawing was by posing for myself. It also was a way of continuing a tradition that was (and continues to be) important to me.

T.J. Mabrey: I Am Grass, I Will Die (1990), folded papyrus paper, 10 by 18 by 2 inches. The portrait was originally done while I was living in Cairo. I didn’t start out to make a portrait of myself, but when it was finished and placed in its little Styrofoam box, I felt just like the piece looked—artificial, expressionless, desiccated, and limited by a “framed” existence within the diplomatic community in which I lived. A couple of years ago (2015) I reframed the piece, putting it into a straw box. It now appears more at home.

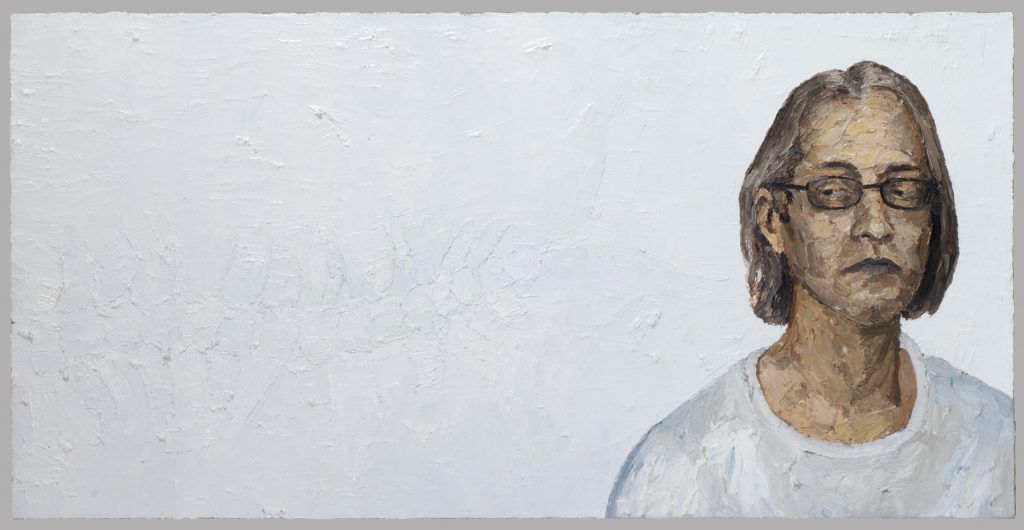

James Deeb: 25,000 Miles from Home (2011), oil on canvas, 20 by 40 inches. I got the idea for this painting from a song. I was stuck in traffic. It was a sweltering day, and the air-conditioning in my truck was broken. An old Bob Marley song came on the radio. It was raw, recorded live at a Chicago club in the early ’70’s. He was singing about slavery and being 8,000 miles from home. His voice was so forlorn, and it occurred to me that he would never feel “at home,” never feel comfortable in his own skin. He was 25,000 miles from home. I suddenly felt the same way and started working on this piece soon after.

Greta Young: Exploding Selfie (2015), mixed media on unstretched canvas, 73 by 47 inches. In this crazy techno-obsessed world, the selfie is the most popular form of self-portraiture. This is a take on the cell-phone camera image—with some expressionism and a few exploding drawings in the mix. Sometimes Sometimes I feel like I’m exploding with all this high-tech stuff mushing things up.

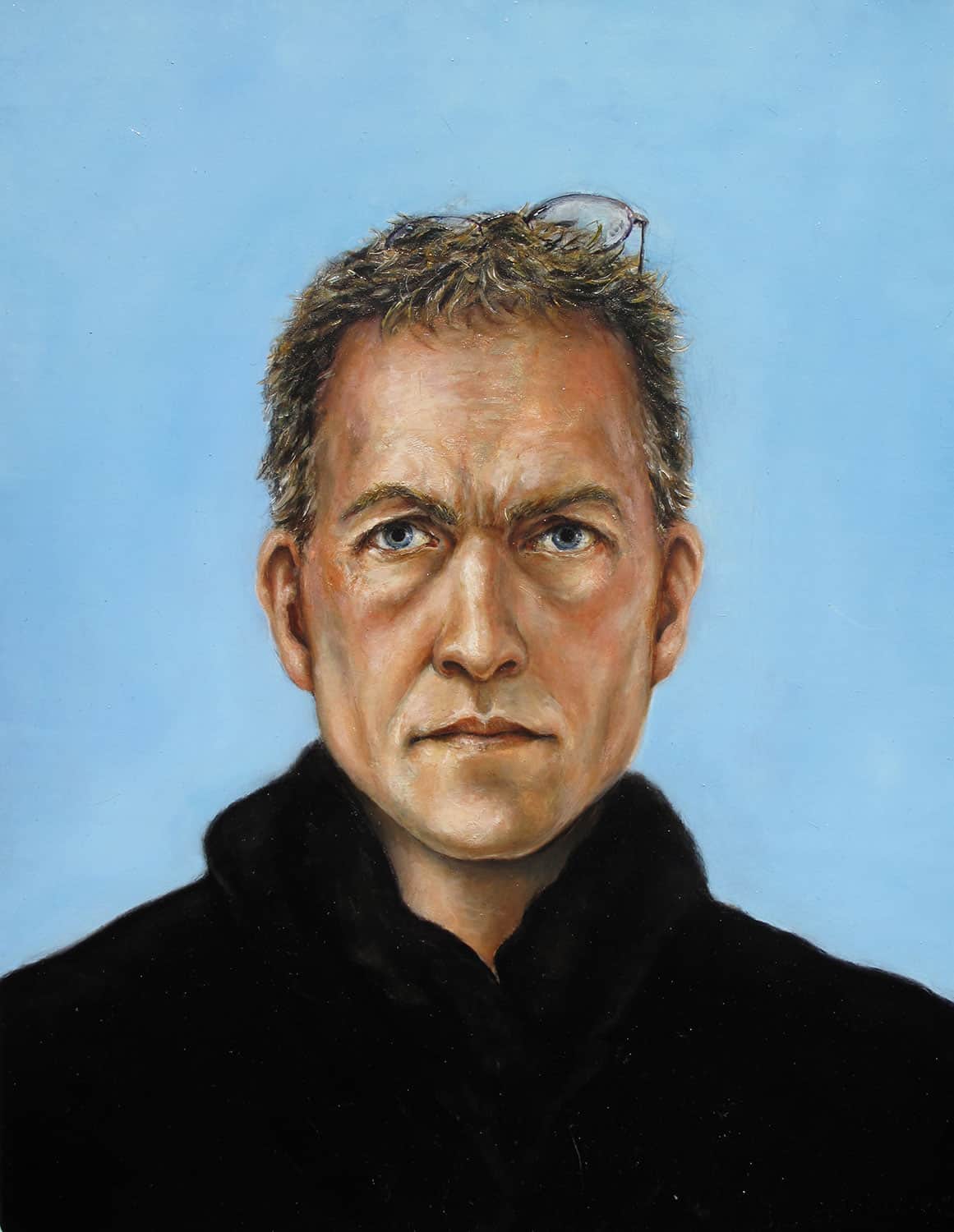

Daniel Barber: Self-Portrait (2013), oil on panel, 20 by 15.5 inches. My practice as an artist involves rigorous research into the nature of perception fueled by deeply somatic memories of my daily immersions in the woods or sea, and self-investigation. I work predominantly from life, and the labored observation and complex process of representation from initial sketch to finished work is, itself, a crucial element of my art. Months spent scrutinizing myself in a mirror or gazing at another person as subject results in an image that I hope resonates with the viewer as somehow familiar and acts as a catalyst for the viewer’s own introspection.

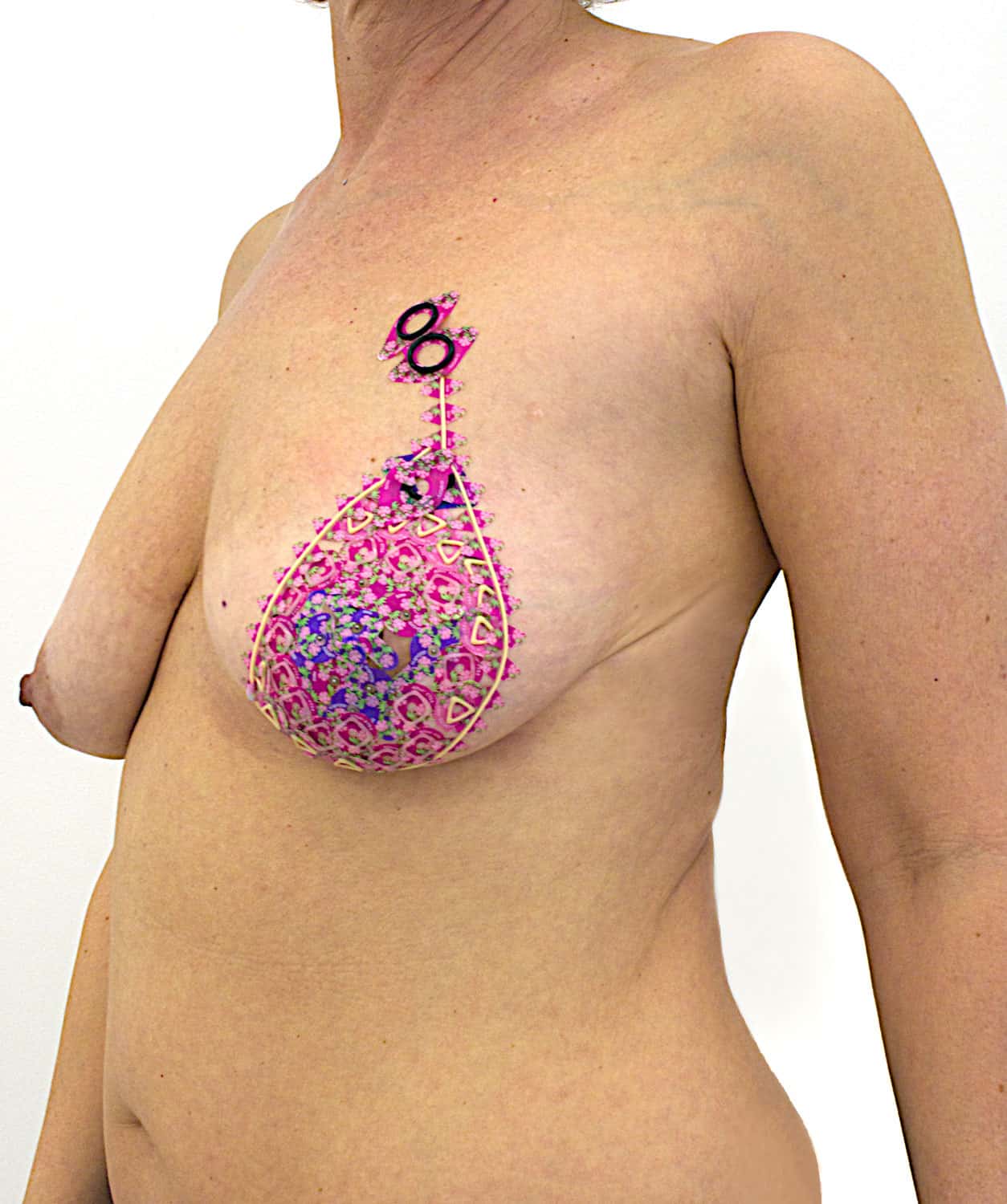

Arlene Rush: Days After II (2012), digital print, 30 by 25-1/16 inches. Because my mom suffered two bouts with breast cancer, I have been regularly going for mammograms since the age of 35. I loved the colorful stickers they use to mark your nipples before imaging, and I always wondered if they were designed that way—bright and cheery—to distract from a serious procedure and its possibly dire consequences. When I was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2011, I had the impudence to ask the tech for a bunch of stickers to use in my art. I had no idea what I was going to do with them, and days after the diagnosis, back in my studio, I decided to start pasting them on my breast as the techs did at the radiology center, but in an entirely different way. The exercise was similar to sculpting as the stickers became a symbolic mapping of my body as a journey. Even though I was consumed with worry over the diagnosis and treatment, I took out the camera and did several self-portraits for a series, ‘Days After.” I chose not to include my face, believing my body had become the face for many.

Melissa Stern: Self-Portrait as an Artist (), clay, oil paint, ink, objects. 34 by 13 by 9 inches. I make art that is mostly figurative. It is also psychological, emotional and darkly funny. So it would make sense to say that I think that everything I make is in some way a self-portrait. I don’t call them “self-portraits,” nor do I consciously think of them that way. I just make the people and stories that are in my head. There are only three that I titled “self-portraits.” They each capture a pivotal moment in my life, and I suppose that is what moved me to designate them as self-portraits. But don’t you think that everything that anyone makes is in some way a self-portrait?

David Herd: Unfinished Self (2015), Oil on board, 14 by 9.5 inches. I don’t like doing self-portraits, I don’t like looking at myself, in all honesty. It’s a very naked confrontation. This one was started during a period of turmoil in my life and looking at it reminds me of that time and makes me uncomfortable. I worked partly in the mirror and partly from photographs for the eyes. It doesn’t even remind me of myself now, but it reminds me of the discomfort that I once felt with myself.

Mimi Saltzman: Looking for Me (2016), collage and acrylic on canvas, 60 by 48 inches. These are my own clothes. I painted the life-size figure falling down, like the explosive items in the scene from the movie “Zabriskie Point.” My husband, Trond Myrh, was dying while I made this.

Simon Dinnerstein: Emerging Artist (1988-89), Conté crayon, colored pencil, pastel, crayola, oil pastel, 12-5/8 by 28-1/2 inches. This self-portrait owes its existence to my wife’s wonderful and inquisitive class turtle, Peter. Her four- and five-year-old students loved Peter and claimed that he could read. A book perched near him dramatically showed the page turned every evening. Renée always brought the turtle home for the summer, and one year she asked if I could do a drawing of him. I said I would try and would show it to her when it was finished. Many questions were thrown in my direction about the new project. Finally, Renée came upstairs to my fourth-floor studio and I showed her the drawing that I had been working on for the past few weeks. I remember her laughing hysterically for five minutes straight, and when she finished, she found herself worried and very disturbed by this vision. The sense of quest and containment, of goal and obstacle, provides some of the ambivalence of what creating art is all about.

Top: Rembrandt van Rijn, Self-Portrait with Plumed Beret (1629), oil on oak panel, 35.3 by 28.9 inches

![TJ Mabrey, Self Portrait, I AM GRASS, GRASS WILL DIE, I WILL DIE, Folded Papyrus paper, Approx 10 x 18 inches[2]](https://vasari21.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/TJ-Mabrey-Self-Portrait-I-AM-GRASS-GRASS-WILL-DIE-I-WILL-DIE-Folded-Papyrus-paper-Approx-10-x-18-inches2.jpg)

all of these self expressive pieces work and are a bit painful, like confronting oneself usually is

lots we don’t want to have to see the art is all superb

Ann – These intimate portraits that you chose are so touching – so personal. Confronting oneself is a difficult encounter.

Each self portrait above move me in different ways. Each story resonates in a different way. I admire the courage of self seeing that each artist engages in.

The one that moves me in an intimate way though is David Herd’s Unfinished Self. Bravo to all and to Ann for exploring this topic among Vasari21 members.