More so than most, Leslie Parke grew up with abundant encouragement to embark on the path of an artist. At the age of five she was studying art books on the living room floor of the family house in Scarsdale, NY. (“I had the childish desire to live inside a painting because the spaces were so extraordinary,” she says.) By the time she was ten, her mother sent her to Saturday classes at the Museum of Modern Art, after which she would catch a bus uptown and head for the Guggenheim, the Metropolitan, and the Frick. What she calls “the background noise of her life” included a neighbor who had an amazing collection of African art, along with masterworks by Calder, Le Corbusier, the Charles and Ray Eames, and Jimmy Ernst. Another neighbor was a “housewife who painted landscapes and made figurines of women in the traditional Japanese way,” she says.

Parke’s high school years were spent at a progressive private academy in Vermont called the Woodstock County School, which adhered to the John Dewey philosophy of learning by doing. “They had an art loft, a big open room where you could work, and we were allowed to go there any time we didn’t have other commitments.”

When it came time for college, Parke went first to Mills College in Oakland, CA, for a year (Elizabeth Murray and Jennifer Bartlett are among the notable alumnae), but didn’t find the place “very inspiring.” She transferred to Bennington College in Bennington, VT, where the faculty included painter Pat Adams, sculptor Isaac Witkin, and critic/artist Sidney Tillim. Kenneth Noland and Jules Olitski were in and around Bennington and on her radar, and Olitski, in particular, was an early inspiration. She saw his painting Cleopatra Flesh (1962) at MoMA when she was still a kid and “was completely gobsmacked by it,” impressed by how he used space, and “how the forms floated off the edge of the painting,” she says. “It totally changed my ideas about what the surface of a painting could be.”

After obtaining a graduate degree from Bennington, and working half-time in the admissions office, Parke teamed up with a German documentary filmmaker named Michael Marton, who was also her boyfriend. They made about eight films together, including “Watch Me Now” about young boxers at Gus d’Amato’s gym in the Catskills (one of these was the 15-year-old Mike Tyson). The artist worked as the sound person and assistant camera woman, carrying a video recorder that weighed about 30 pounds on her back. Though film was not to be in her future, she describes the experience as formative: “It gave me a lot of courage about moving into an unknown situation and dealing with It. That was crucial for anything I wanted to do later.” A dozen years after first seeing the young future champion, she would also complete a series of paintings about boxers, using a press pass from Tyson’s former trainer to take photos of fights ringside.

Beginning in 1986 and continuing for about eight years, Parke made a series of works based on images appropriated from other painters—Matisse, Ingres, and Giotto—that often explode in exuberant shards. What interested her in the Matisse series, for example, was “taking a known image and relating it to the shaped canvas.”

Then in 1994 she landed a grant to spend five months in Monet’s gardens at Giverny and thought to herself, “What am I going to do with this experience? You’re in Monet’s territory but you don’t want to make some crappy Monet painting. How can I appropriate this situation for my own work?”

The answer was to go in a radically different direction. For several years, in both photography and painting, Parke pursued representational subjects that are breathtaking in their range and dazzling in technique: tableaux of antique china and crystal, inspired by her grandparents’ summer home; delicate tablecloths in all their wrinkled complexity; photorealist depictions of large lush flowers; a series of figurative works based on the iconography of Adam and Eve; and colorful jumbles of recycled cartons, plastic bottles, tin cans, and other detritus of our consumer culture.

The many different directions all started to come together for her, Parke says, when she did a residency in 2008 at Vallauris in Provence, where Picasso made his ceramics. Purely by chance, she took a photo of an almond tree in bloom. “That started a whole series of paintings that were at first representational, but the tree looked something like ‘Jackson Pollock took a walk in the woods.’

“Because of that photo I embarked on a whole series that entailed first doing a representational painting, and then doing a series of lithographs based on that painting, and then doing a series of digital prints, also based on the painting” she says. For the last ten years, she has found herself easily moving in and out of different mediums, but tending generally toward a kind of abstraction that may remind viewers of some of the heroes of 20th-century Modernism: Brice Marden, Cy Twombly, and, yes, even Jackson Pollock.

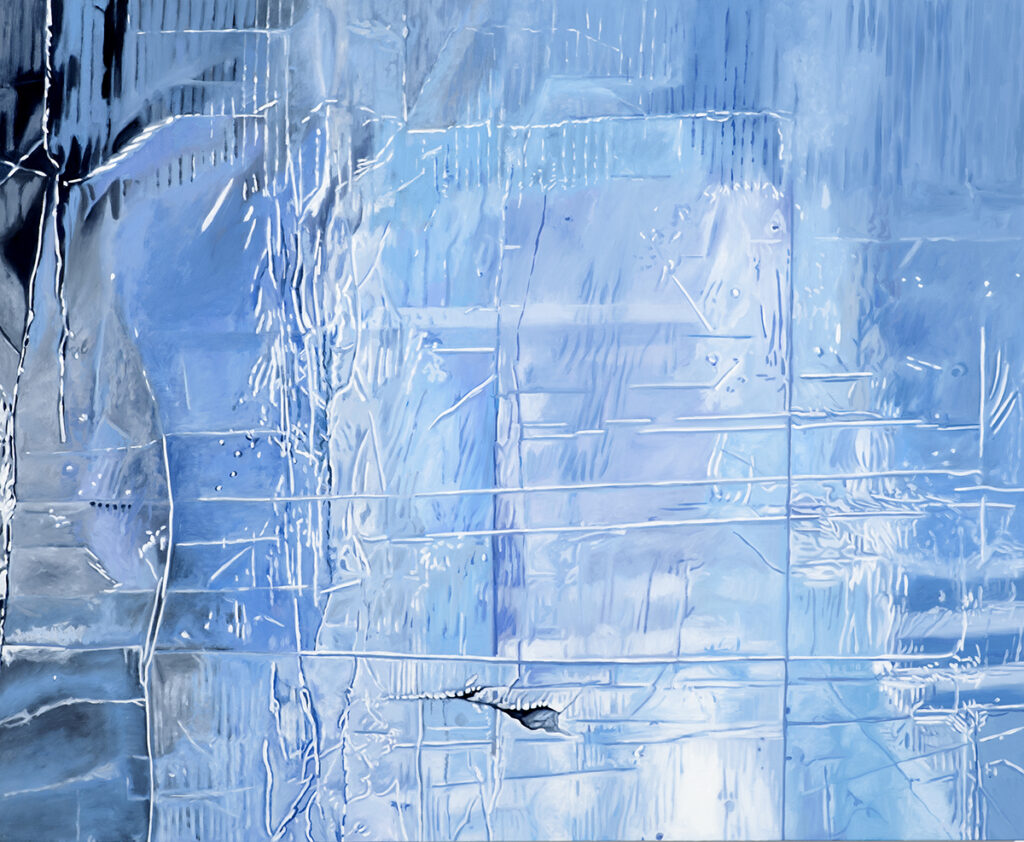

For more than 40 years, Parke has lived in Cambridge, NY, in an apartment she has painted so that it seems she is living in interiors as imagined by Pierre Bonnard, near a spacious studio that can easily accommodate the kind of large scale she favors. During the pandemic, she found inspiration at home, making paintings of the patterns of frost on her windows, works that—like many others—rely on the subtle tension between realism and pure abstraction.

“When Covid hit, I knew we’d be in it for a least a year,” she says. “I didn’t know what would happen with dealers and shows or other aspects of the market, so I got a government loan. As artists we live with a certain level of uncertainty, but because I had the loan, I could pay my bills. Now suddenly everyone knows what it’s like to live this way. They get it.”

But, she adds, it’s a good life and she wouldn’t trade it for any other. “I still have sales, and I’m totally excited about the work.”

For more information about Leslie Parke, please visit her website: https://www.leslieparke.com