Judy Signunick

It’s a rare contemporary artist who dares grapple with literary masters. Cy Twombly summoned the ancient classics through a series of paintings that pay homage to the gods and heroes of Greek mythology. Frank Stella has been inspired by the 18th-century tales of German Romanticist Heinrich von Kleist and Herman Melville’s epic Moby Dick.

And for nearly 15 years Judy Sigunick has been jousting with Shakespeare, first in a collection of wildly inventive ceramic sculptures and more recently in a series of paintings called “Letters to Shakespeare,” which are about to be published as a book.

Sigunick has been an artist for much of her adult life, but it was not till after raising a family and returning to get an MFA when she was in her fifties, and then stumbling into the Bard as a teacher at Dutchess County Community College in Poughkeepsie, NY, that she discovered a subject that would fully engage her imagination. In 2005, she met a fellow adjunct professor, who was both a potter and a Shakespeare scholar, and the two became friends. “I sat in on her class one semester, and I was hooked. I sat in on other classes,” Sigunick recalls. “We started having conversations about Shakespeare. I later discovered that my son, Adam, a computer programmer, was also totally into Shakespeare. We watch the plays, we talk about them.”

There is, of course, a universe of themes in Shakespeare to keep scholars, artists, poets, readers, and any lover of literature enthralled for more than one lifetime. But Sigunick has fastened on a few motifs in particular. The Bard’s fondness for gender-bending dilemmas and cross-dressing, so relevant to our own times, has led her to imagine characters like Viola from Twelfth Night and Caliban from The Tempest.

“Shakespeare’s characters are the ups and downs and freefalls that define an artist’s life,” she wrote in a blog entry a few years ago. “Viola [from Twelfth Night] is my current companion. She is a twin. She thinks she has lost her brother to a shipwreck. Her cleverness and earnestness catch her a fabulously cute guy, in fact a duke, despite her disguise as a boy…..I want to disrupt history, step apart from horizontal lines and bring Viola to life as a blend of contemporaries from various places.”

To that end, a subtheme from a recent show was “Thirteen Ways of Looking at Viola” (a title borrowed from Wallace Stevens’ poem “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird.” And there were ceramic sculptures titled When Viola Falls in Love and When Viola Finds Sebastian. A year later (2016), a show at Sylvia Wald and Po Kim Gallery called “Vanishing Boundaries” drew on The Winter’s Tale, which as the announcement noted, “contains stories within stories, one boundary seamlessly flowing into another until they coalesce into a whole. It begins with a storybook marriage destroyed by jealousy, followed by a debate over whether art is an unnatural construct or a conduit for improvement, and segues into a dreamlike ending in which love conquers jealous and forgiveness turns the tides of tragedy.”

Elephants were also featured in the Wald Gallery show, but big animals were a part of Sigunick’s vocabulary well before she became entranced by Shakespeare (she had previously executed commissions for a life-size concrete rhinoceros and a 60-foot whale). She once spent considerable time at the Bronx zoo looking at elephants. “There’s something in my soul that connects with them,” she says. “I worship them. I think their form is one of the most exquisite on earth—the way they move, the way they cohabit, the matriarchal nature of their society.”

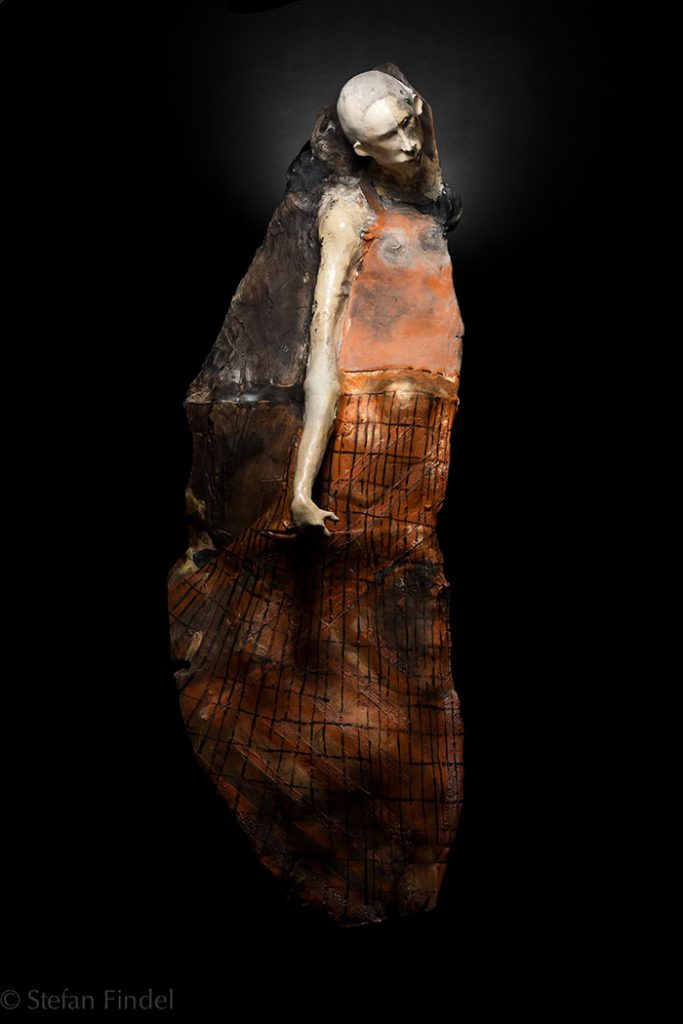

Sigunick’s methods involve a complex array of ceramic modeling techniques that she described to critic Nava Atlas as “coiling and slab building, wheel throwing, and carving. Once the form is completed. I cut it down to fit inside of my electric kiln, fire it and apply clay slips and glazes, firing it once more in the electric kiln. Afterwards I may decide on a reduction firing in sawdust — akin to traditional pit firings.” Happy accidents like cracks and breakage are welcome, as they allow for reassembling pieces in unexpected ways. The surface is then approached as one would a painting, with mixed media such as paints, tinted epoxies and metals.”

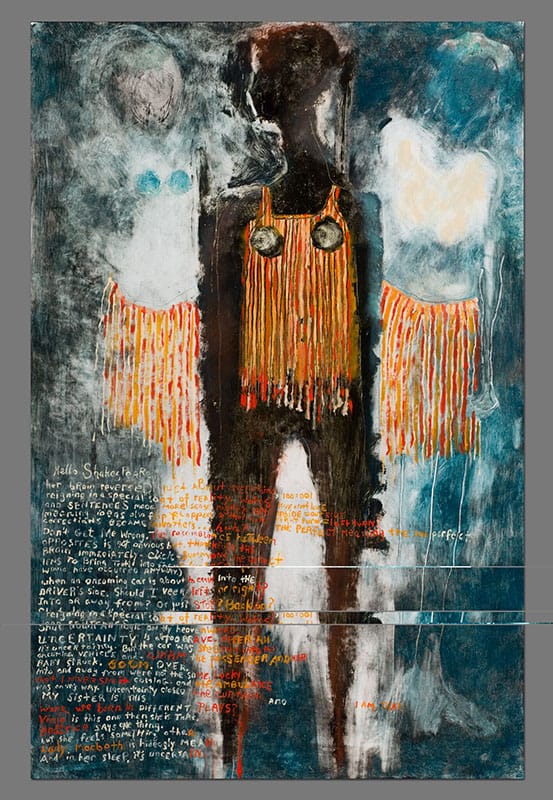

The paintings in the series and forthcoming book Letters to Shakespeare offer a similar alchemy of color, line, pattern, and characters who may or may not have to do with the Bard’s own fantastical imaginings. There is a wonderful amalgam of elephant and human, for instance, in the one titled Noble Elephant. In each work, she opens with a cheery “Hello, Shakespeare,” and offers up a kind of freewheeling diary of her day-to-day life, reminiscences (for example, of a ruptured appendix during a trip to Greece, or the loss of her infant daughter in a car crash), commentary on our current political situation, and ruminations on the characters in the plays, Throughout, Sigunick expresses her appreciation for the inspiration afforded by a long-dead playwright: “Your celebrated works don’t always get me to where I’m going, but your words wash over and get into me—thrumming, sparking, probing, bringing me to my own two feet—tracing backwards, from your world to mine, clutching a paint brush, riding the waves of color, pulling clay rhythmically upwards, compressing dense matter until… until…until it’s stone. Because of you and beyond you, I’m indebted.”

In the book, the paintings contain each letter inscribed in an almost childish hand, spilling across the surface with uninhibited velocity, juxtaposed side by side with a more readable text. It’s a rare collaboration of talents across the centuries, and a source of delight for the reader, who can both peer into an artist’s mind and savor her thoroughly original imagery.

Ann Landi

Top: Buddha Girl (2017), ceramic, epoxy, concrete, wood, 17 by 21 by 8 inches

I’m so glad that Judy’s work is getting this attention. I was so captivated by it when I visited her studio- finding the work to be a fine intersection of fantasy and truth.

Brava Judy thanks so much Ann

Great article about Judy. It gives a real sense of the depth of her engagement with the work, on multiple levels. Well done Judy, Well done Ann.