The art that made artists want to be artists

In almost every artist’s life there are inevitably one or more works that ignite a spark or at least plant a seed, provoking the notion that art could be a dedicated calling, or at least a subject of serious study. Sometimes a piece of art may engender a change of direction; sometimes it remains buried in the subconscious and is recalled only when summoned (as in a post such as this).

I wanted to offer a “grand prize,” a hardbound copy of Mary Gabriel’s sprawling and deliciously readable Ninth Street Woman, but the entries were all so good that I wrote each name on a slip of paper, dropped them into a hat, and pulled out a winner, which turned out to be Ashley Cooper. As far as I’m concerned, you are all winners and deserve a big round of applause for letting us know about the works that first turned you on to art.

Ashley Cooper: I went to college in Athens, GA, to major in art. Athens, at the time had a big music scene, and I thought that was cool, but I knew that I wanted to paint. During my first semester, I learned that painting was dead, my work was illustrative, and everyone in the art department had picked up guitars and started bands. Lacking musical talent, and having discovered an affinity for dead things, I became a classics major. I set out to learn Latin and Ancient Greek.

The summer after my junior year I saw a Titian show at the National Gallery in Washington, DC. The last room of the show displayed just one painting—The Flaying of Marsyas—and I stopped cold in my tracks. I had been trying to translate this story in my Plato class. It had meant nothing to me. Now here it was, vibrating off the wall. I suddenly understood what “illustrative” meant and that this was not illustrative. I also understood that some things don’t translate. All that Titian conveyed could not be expressed in any other way but through this one unique object hanging on the wall in front of me. It was for me, at that moment, simply the most wonderful thing in the whole world—better than any book, or building, or movie, or rock concert. This was an epiphany.

Now I am a painter with a teenage son who likes to make music on his computer. I say, “Why don’t you learn to play the guitar?” He says, “Mom, the guitar is so dead.” Maybe…maybe not.

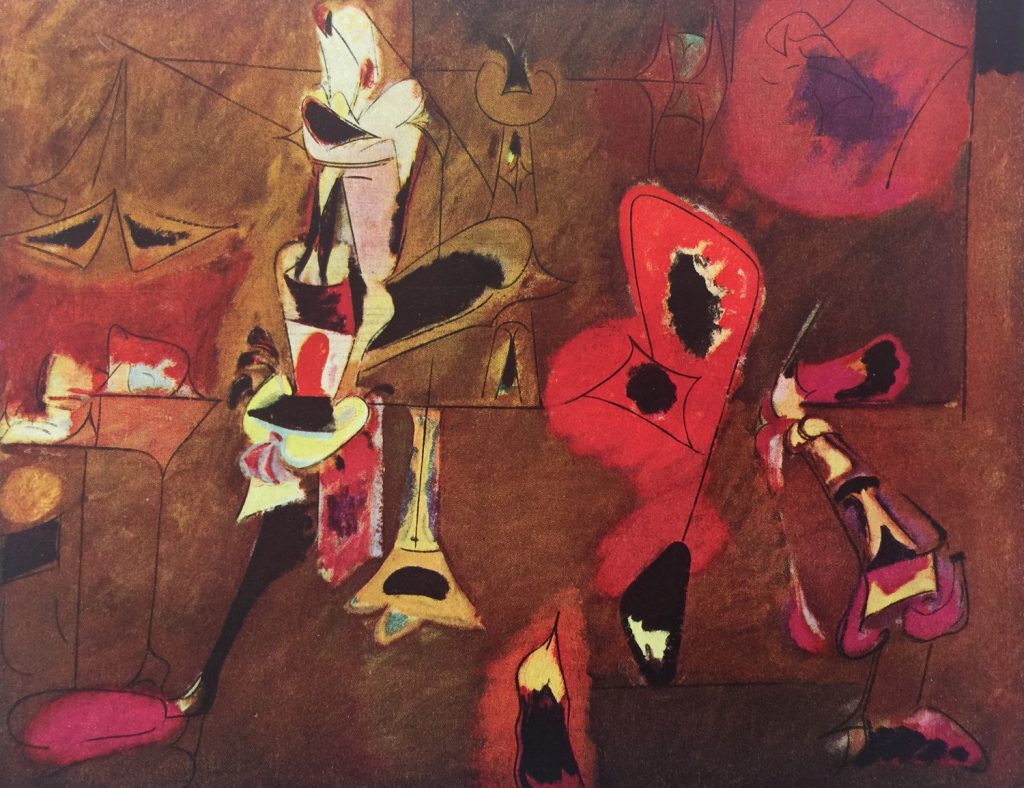

Jane Shoenfeld: I was already in art school at Pratt Institute, when this happened: MoMA was a subway ride away and when I walked into the room where Arshile Gorky’s Agony was hanging, I was pulled toward it and riveted. My experience in seeing Agony the first time was not so much one of visual perception but a more total sensory experience. The painting held tremendous emotional power for me and impacted me internally on levels I could not identify.

Yes, I was a lonely young student dealing with all sorts of pain, and very vulnerable. But I had not had an experience of art like that before, where I was connected to a powerful and mysterious place inside myself through looking at a painting. This is still a measure for me, of how I want to paint and how I hope my work will impact others.

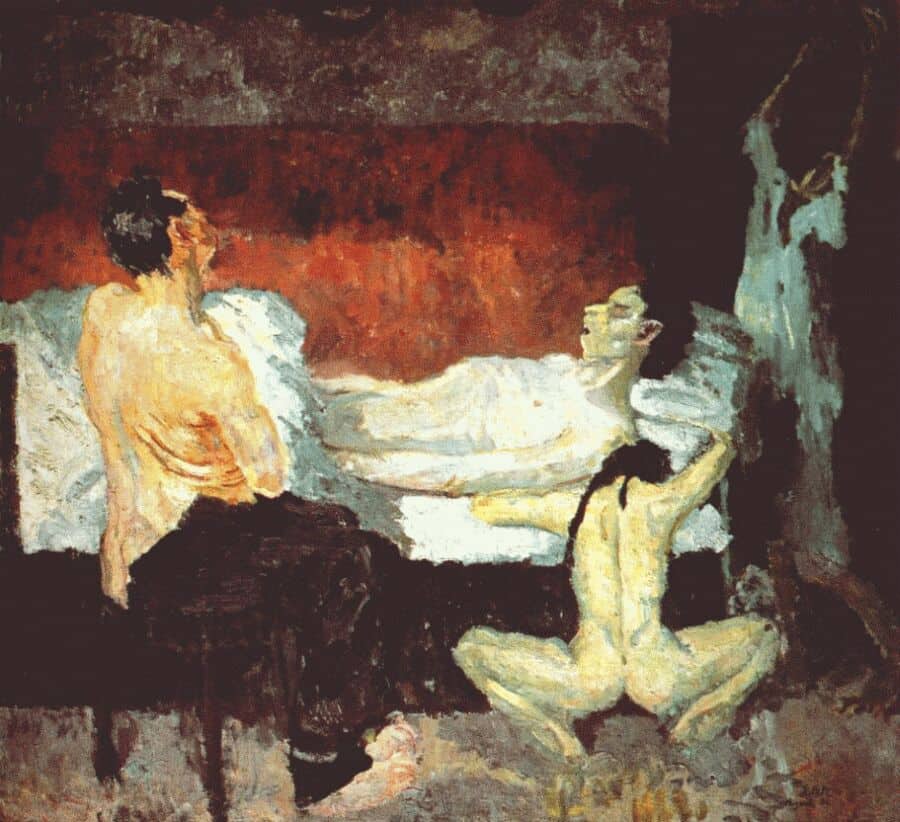

Joan Snyder: When I was a very young painter, I came across Max Beckmann’s The Death Scene at a show of the artist’s works at the Museum of Modern Art in 1964 or ’65. My beloved grandmother Dora Cohen had recently died—the first death I experienced of someone I loved. I was very upset by the demeanor of those who attended her funeral. Everyone was so quiet, polite, non-reactive. There was a ceremony by a rabbi who didn’t know her or anything about her. She was an orthodox Jew who immigrated from Russia with her brother Abraham when both were teenagers. She was uneducated, spoke broken English her whole life, and loved me with a mother love I never got from her daughter, my mother. I took care of her as she aged. So when she died at 86, I too, as in the Beckmann painting, wanted to be nude, crouching at her graveside, screaming, my arms waving in the air. It seemed so much more appropriate than the unemotional, meaningless funeral that I attended. After that I made many crouching nude paintings and prints…some heavy, some angelic, some in a worship pose (don’t ask) and some with great humor.

Kerith McCoy Lisi: Wandering through the Tate Modern in London, I walked into a room exhibiting the work of Louise Bourgeois, an artist I previously knew nothing about. I was particularly struck by Ode à la Bièvre (2007), a cloth-bound book which, for the purpose of the exhibit, was shown with each page framed individually and hung in a grid. The piece was so many different things at once: a book, a diary of sorts, a fabric collage, a poem, a memory transformed, a love letter to the river of the artist’s childhood. Bourgeois combined archival dyes, type, hand-stitching, and appliquéd fabric from fragments of her own clothes.

The incorporation of such personal materials and use of color in her storytelling made me reconsider my own perception of what constitutes art as far as materials and means of expression are concerned. I had to question why skills historically placed in the category of “craft” (sewing, textiles, embroidery, quilting, etc.) are often considered “women’s work.” I left that day with a deep respect for work created stitch by stitch, a commitment to look more closely at how things are made, and a desire to use unexpected materials as a means to tell a new story in my own work.

The discovery that the work had been made late in Bourgeois’ life stripped me of the excuse for not having started early enough (I was 43 at the time).The fear of not doing finally became greater than the fear of doing. This piece, and many other works on paper in the exhibit, felt like peeking into the artist’s thoughts, unfiltered, both the light and especially the dark. I left that day (only five or so years ago) feeling like I had been granted permission to speak up unapologetically, that keeping quiet and not creating was no longer an option, or at least no longer an option for living a fulfilling life.

Sheila Miles: I was raised in Indiana, where an artist’s success was measured by his ability to paint barns, cows, and horses. (I could do all those by the time I was 14.) But in my first year of college, 1971, I went to the Art Institute of Chicago and saw Georgia O’Keeffe’s Sky Above the Clouds IV hanging in the stairwell of the museum. I remember it was the first time I saw a work by a woman in a major museum. When I was studying art in college so few women were represented in art history books, besides Rosa Bonheur, O’Keeffe, and Audrey Flack.

Seeing a piece in person, by a woman (even though it was in a staircase), I was personally inspired to continue my art pursuits. There was hope after Indiana, women were serious artists and could hang in a museum.

Anna Wagner-Ott: At 16 I went through a lot of personal turmoil and after I left home, making art kept me sane because I could escape into my sewn collages. During that time I fell in love with Alberto Burri’s artworks because he did not create the kinds of realistic landscape paintings I grew up with but used unorthodox materials such as tar, pumice, aluminum dust, and burlap. I was drawn to the way he sliced and ripped his canvases and then took a needle and thread to integrate the parts back together. Burri used burlap and monochromatic colors and then added red or orange that I saw as his rage color. During those years I tried to emulate him by also using found materials and escaping into these sewn collages that had a rawness about them. It felt like I was sewing up parts of myself. Then when I went to university I lost myself and tried desperately to fit in, so I painted what was expected of me. After I graduated it took many years to get back that love for making art.

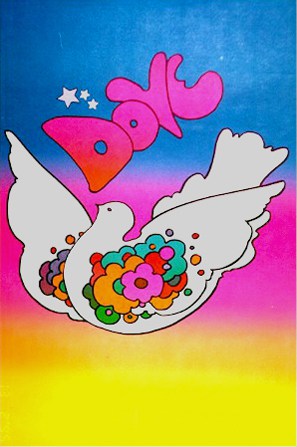

Mary Lonergan: In the early 1970s, my brother received a gift for his birthday, a beautiful Peter Max poster book. I was 11 at the time and knew nothing of art, really, and had no exposure to what anyone would consider serious art, but this book had a profound effect on me. I essentially stole it from my brother and slept with it, keeping it under my mattress in case he came looking through my room.

This piece Dove, from 1968, made me brilliantly happy! I was astounded by the power of the image to completely change my mood, and I kept wondering how he did it.

At that age and for many years after, I didn’t know that you could become an artist. I thought you either were one or you were not. I accepted that Peter Max was some kind of genius and I shelved my own ambitions, but I continued to wonder at the exchange between myself and the image and how did that happen.

Fast forward to modern times, I started painting in 2003, at 44, after being laid off from yet another corporate job. I saw an ad for an all-day painting session—bring your own lunch—and the host provided paints and other materials I was hooked at the freedom I felt while painting by. After several sessions I had painted something that felt so freeing and had so much movement and emotion in it, that I knew the thing I was always wondering about, how did he do it, wasn’t something outside of myself, it was intrinsic and inseparable from me. That realization is truly what moved me to paint.

And I still get a thrill looking at vintage Peter Max posters!

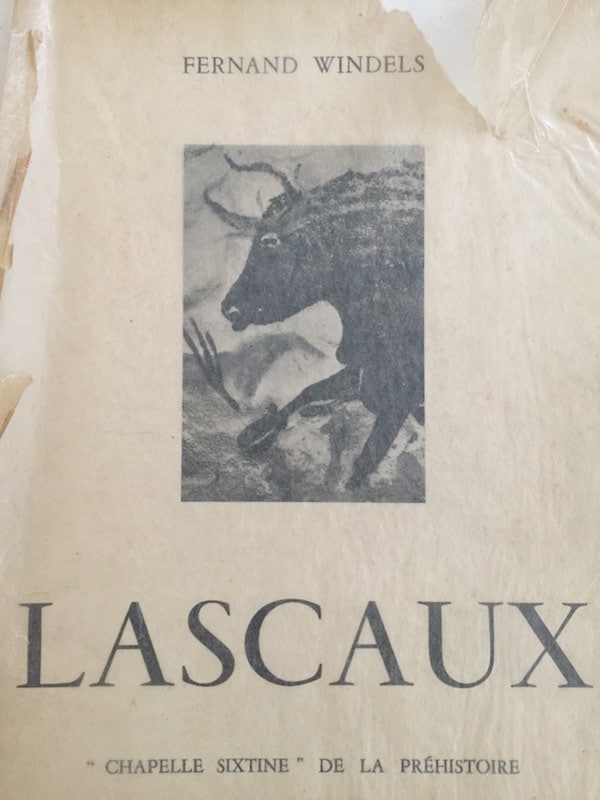

Millicent Young: When I was very young—four or five perhaps and small enough to sit under my mother’s desk—I discovered the cave paintings at Lascaux. My mother was an anthropologist and professor and she had been in the caves after World War II. While she was grading exams above me, I became lost in one of her books—a large, soft-cover catalog with many photos and drawings documenting the cave art. I remember every detail of the experience: the smell of the book; the simultaneous sense of recognition and mystery; the way the glassine sheets between the pages made the images even more magical, a shroud I could lift and lower, revealing and hiding the images; the shadowy light; my mother’s stocking-ed legs in my secret room beneath her desk; her disembodied gentle voice answering every question this child had about the caves, the animals, about time; my imagination feverish, creating a story that was also real.

Lily Prince: When I was about four years old, my parents took me for the first time to New York’s Lincoln Center, to the Metropolitan Opera House. As I stood outside at dusk, looking up at the brightly lit glass-front structure, I was completely overwhelmed by the two large Marc Chagall murals that grace each side of the opera house’s sweeping dual staircase. The Triumph of Music and The Sources of Music, both of which are visible from the plaza outside, are 30 by 36 feet each. Massive to a four-year-old.

I had never seen anything so glorious. Huge reds on one side of me and yellows with blue on the other side—they completely filled my line of vision. For many moments, nothing existed but a universe of these reds and yellows, swirling about overhead. This is one of my earliest childhood memories and one of the most impactful to me as a future young artist. It has stayed with me always as a symbol of pure joy, imagination, and possibility.

Jan Anders Nelson: I entered college knowing that I would be in the choir, take classes in theater, and spend as much time as possible performing on the stage in musicals, plays, and of course rock n’ roll. I spent time working as an actor, director, and set designer. And then I saw a painting done by a new art professor at the college, Robert Therien called “Three Bean Salad”.

This large oil on canvas (about 60 by 60 inches, if I recall correctly) served as a semaphore, signaling that a place existed that I already knew, where I could do what I needed to without others pushing and pulling to control my efforts. That place was in the studio, making drawings and paintings, and out in the world, looking through a viewfinder to learn more about how my perceptions of that world were tied to the art I was making.

Robert had attended the University of Wisconsin in Madison, working under Hal Lotterman and Victor Kord among others and was instrumental in guiding my exploration into graduate schools. We talked of Yale and the impact and influence of Josef Albers and those that followed him. I asked Robert about his experiences at Madison and came away impressed that the faculty and facilities were first -ate, ultimately deciding to attend there and work on a master of arts in painting, printmaking, and drawing. During my time working in the studio with Robert, I continued to learn techniques that I use today, and still hear his voice when looking through that viewfinder telling me to make all the decisions before tripping the shutter.

Carole D’Inverno: On a hot June day in 1968, when I was 12 years old, I went on a school trip to Paestum in Campania, Italy. The site is famous for its three ancient Greek temples in the Doric order. In school, our teacher had drilled us on the architecture, telling us about the negative spaces between the columns, how they looked like amphoras.

We arrived near sunset. The bus passed the massive outer walls and came to a full stop in front of the temples. We all jumped out, screaming, laughing, and running.

The sun setting behind the temples, made the columns appear dark, almost black, while the spaces in between were aglow. I stopped hard on my tracks. I remember I started shaking, not knowing how to process what I was seeing, all that mystery and majesty. But to this day, I do remember the words resonating in my head, loud and clear: “Se questa è bellezza, io ne voglio fare parte.” If this is beauty, I want to be part of it.

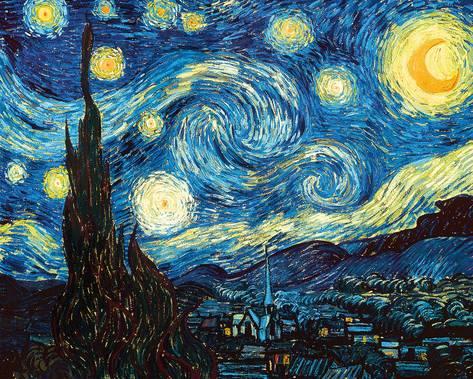

Amelia Currier: When I was ten, art class met once a week, and it was my favorite subject. One day the teacher brought in a pile of glossy pictures by the “classic masters.” My mother and grandfather were both artists, so I was aware of how art fits into life, but only in the context of their work and a reproduction of Pieter Bruegel’s The Wedding Dance that hung over our couch. One of the images in that pile was of van Gogh’s Starry Night. My eyes honed right in on the swirling stars. I didn’t know it was okay to make images come alive that way, as if they were moving! My wide-opened gaze drank in the bold, deep blues, the twisting trees, the energy emanating from its surface, as if by magic.

Interestingly, my son, who is also an artist, was also drawn to van Gogh as a child.

To this day, van Gogh remains the real deal for me—as honest as the day is long.

Who doesn’t love van Gogh at any age? At top, a lesser-known nocturnal explosion: Starry Night on the Rhone (1888), oil on canvas, 28 by 36 inches

Thank you for sharing these Ann! And WOW on that Georgia O’Keefe. Hadn’t ever seen that one.

What a diversity of experiences and sources that bring us into this river we share of art making. Thank you for asking the question, Ann… so grateful to be in this company

I really enjoyed reading all of these and could have read dozens more. Such apt and wonderful descriptions of that transformative moment and expereince when art reaches out and envelops one and becomes the world itself.

Thank you, Ann, for such a thought-provoking topic. It is great to read so many terrific artists’ recollections of their most impactful inspirations. Thrilled to be included!