If you could talk to any artist, dead or alive, whom would you choose? What would you ask?

I know from hard-won experience that artists can be maddeningly difficult to talk to. While some—Frank Stella and Jim Dine are two who come to mind—are on good terms with the English language and have no difficulty explaining why they do what they do, others can be evasive or downright obtuse. I had a hard time getting Alex Katz to offer much more than monosyllables when I interviewed him 20 years ago (maybe he’s grown more loquacious since), and Marisol, as I recounted in an earlier post about studio visits, would not or could not give me even enough information to fill so much as a paragraph.

Nonetheless, there are artists with whom I would persist just for the faintest glimmer of understanding. No, I really don’t care if Mona Lisa was smiling, pregnant, or suffering gas pains when Leonardo painted her, but I would love to know what he and the feisty collector Isabella d’Este talked about when he drew her portrait. I would be curious to know, too, how Artemisia Gentileschi managed a lover, several children, and a thriving business painting for the Florentine gentry.

But of all the great artists whose brains I would most like to pick (and of course there are many), Édouard Manet is the one I would press the hardest to understand just what the hell is going on in some of his paintings. I remember sitting for a good hour in front of A Bar at the Folies Bergère at the Courtauld in London, reading numerous articles about the mirror, the oranges, the tiny dangling legs in the upper left, and being none the wiser for all my research and careful looking. But maybe after a couple of glasses of absinthe, M Manet would take me by the hand and explain, “Alors, madame….”

I wondered if artists fantasized meeting up with other artists—those they admired or even those whose aims were completely different from their own—and so I put the question to a handful of members: If you could spend a hour, a day, or share a meal with any artist from history, who would you most want to talk to? What would you ask? What would you tell that artist about what you’re doing?

Here are their answers.

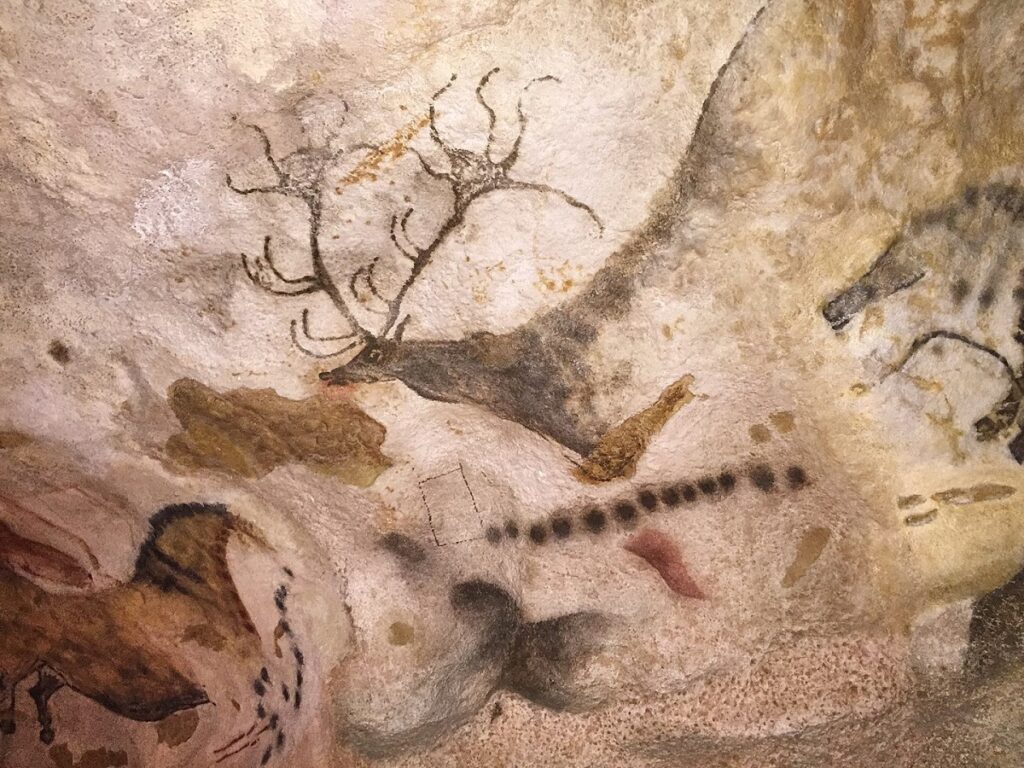

William Norton: If I had my choice of any artist to break bread with and gain better insight into why art is made, I would choose to visit with the first artists who put paint on the cave walls. This is a selfish way for me to justify my own art practice as I have always felt more kinship with those artistic shamans who through force of magic and majesty created works to better grasp their world than these modern fabricators who have become hands-off CEOs. The dilemmas might begin with the complexity of verbal communication, or with their desire to choose me as a meal instead of a compatriot, but let me sit safely in back as they approach their paint surfaces in the flickering firelight as the wonders of the shadows and shapes evolve from the walls. The spirits summoned, the animals and hunters becoming alive, the pigments chosen and their hands breathing into stone. My journey would be complete

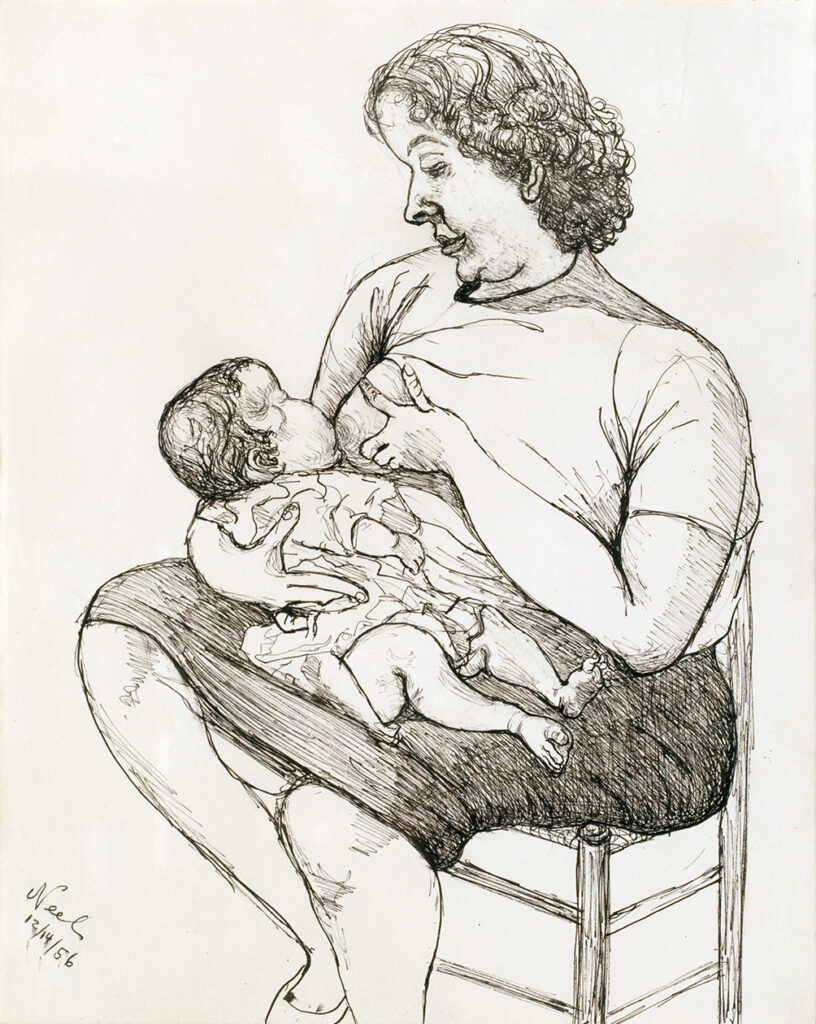

Francie Bishop-Good: I would like to spend time with Alice Neel. I am in awe of her work, her struggles, and her history, and I’m lucky to pass by her work daily, as we own two prints and one beautiful drawing of a woman nursing (it is going to be in a show at the Met). Her work has always spoken to me, and even makes the hair on my arms stand on end! I’d want to know more about how her hard life and struggles all culminated in some of the most luscious paintings of the 20th century. I would also like to chat with her about her life in Philadelphia because that’s where I went to art school. There is an intimacy that is so unique to Neel. I think one question I would ask would be about her choice of blue for the outlines in most of her portraits.

Pacha Wasiolek : Egon Schiele first came to mind because he is the reason I started drawing nudes with gouache and graphite, colored pencils, and ink. I love his line and his contorted tortured poses, limbs and faces. Then I thought of Jenny Saville because of her huge masterly oil paintings of massive women’s bodies; her paintings of women having plastic surgery, often showing the marks left behind by the surgeon’s hand, also make me very uncomfortable. I like art that is disquieting.

That said, although I love their use of gouache, line, and oil paint, I’m not sure how interesting either would be to talk to. So I started thinking, what artist would I most like to listen to? What answers to my questions would be the most surprising and thought provoking? Who would I be the most curious about? Even though I’m not a sculptor, I realized that artist would be Louise Bourgeois. We would talk about spiders and mothers.

Lastly I’d also like to talk with Agnes Martin but I don’t think she would talk to me. I have a friend who knew her when she lived in New Mexico. Agnes told a story about how her mother would kick her out of the house in the dead of winter. She would stand on the frigid porch and stare out at the horizon. I’m imagining that helped calm her and I would ask if that horizon is where her grids came from. I don’t know if the story is true, and I’m sure she wouldn’t tell me.

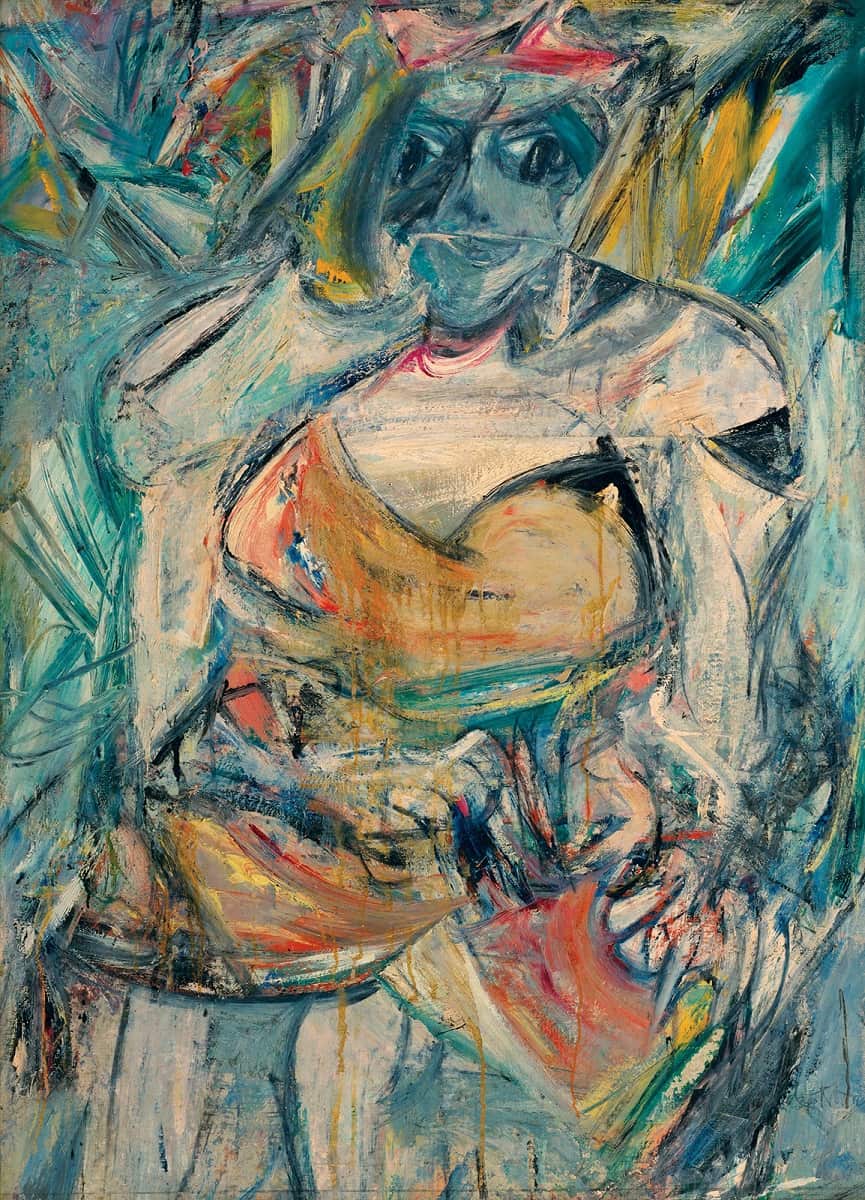

Christopher Benson: I’d love to spend an evening with Willem de Kooning and J.M.W. Turner at the same time. That’d be wild! We’d have roast beef and Yorkshire pudding and a nice expensive port—and a bottle of single malt Glenmorangie Scotch for de Kooning.

It would start out terse, uncomfortable and polite. Gradually we’d all get boozed-up and on to a first-name basis; then I’d pester them to tell me about how they know when a painting is really done I would prod them into switching places. Bill and I would gang up on Joe and make him confess that Norham Castle Sunrise wasn’t really “unfinished” at all—that he got it to where he left it and realized he couldn’t take it any further. Bill would get maudlin about how he secretly just wanted to paint fat, naked Dutch ladies.

They’d both get loud and sloppy and throw things. Bill would take a swipe at Joe and Joe would smash the whiskey bottle, sweep everything off the table and start painting a sunset with the spilled spirit on the tablecloth. Then Bill would snatch up a chocolate biscuit and draw tits on the sunset, and Joe would push him out of the way and rub the eggy Yorkshire pudding over the whole thing.

Then they’d tear the cloth off the table, pin it up on the wall with a pair of bone-handled oyster forks and start arguing about what to do next. Soon it would come to blows and I’d have to break it up by pushing in with a pitcher of clotted cream and beef fat to glaze the entire production.

We’d stand back and survey the work, judging it complete, then march off into the night, singing a medley of obscene bar songs.

Marina Cappelletto: I would like to have a conversation with Agnes Pelton and Gertrude Abercrombie. If we were to meet up, I would let them know what I appreciated about their work: the silent, meditative quality in Agnes’s, and the unusual juxtapositions in Gertrude’s, and I would share with them that those are also qualities I focus on in my own work. I would like to spend an afternoon in a museum with each of them, discussing the works on display. Since Gertrude was from Chicago, I would meet her at the Art Institute of Chicago, and I would suggest starting with the paintings by Giovanni di Paolo. Agnes spent a good part of her life in Brooklyn, where I live now, so I would meet her at the Brooklyn Museum, and recommend that we start in the Egyptian wing. While making our way through both museums, I would ask them to show me the work each of them found most compelling.

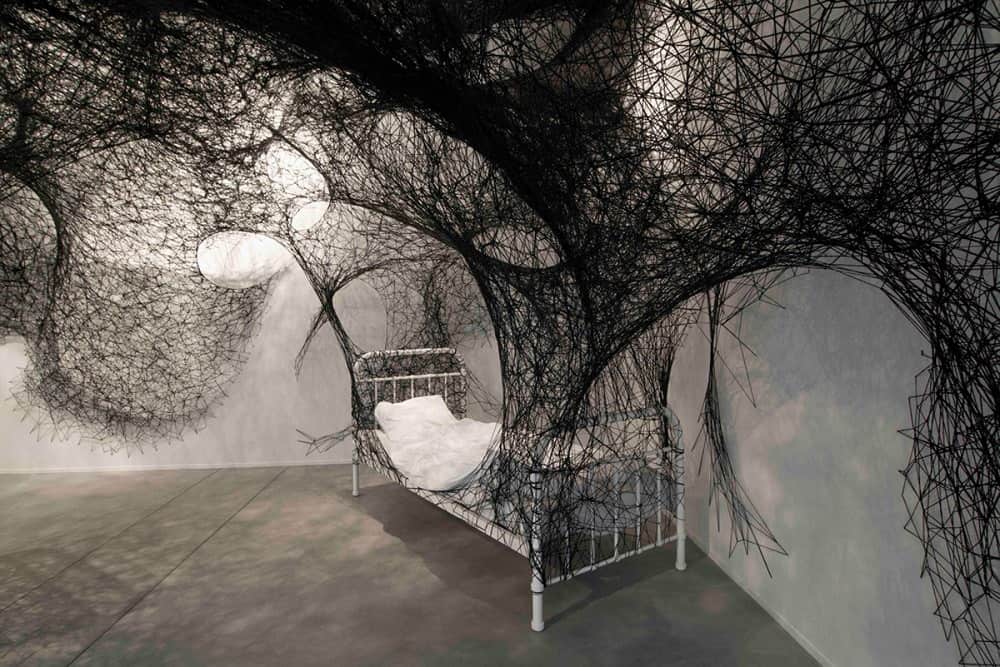

Christine Aaron: With the increased isolation imposed by the ongoing pandemic, imagining a place and time where people can gather without fear, and share a meal and long discussions into the night seems positively magical. I would gather artists I deeply respect and to whose work I intuitively respond. Three women, three men, three living, three no longer with us. All involved in a deep investigation of material and materiality in their work: Eva Hesse, Jack Whitten, Alberto Burri, Judy Pfaff, El Anatsui and Chiharu Shiota.

Imagine a late afternoon in the early summer. A large old pine table is set beneath several trees through which a gentle breeze rustles. Platters of crusty warm bread, cheeses, grilled vegetables, salads and fruit. Pitchers of wine, water and iced tea. The pace is unforced and there is plenty of time to move around and engage in multiple conversations.

From painting to sculpture to installation each artist brings his/her own reasons for choosing unconventional materials and has a unique sensibility in the use of physical space and dimensionality.

I imagine a lively exchange ranging from material choice and meaning, specific inspirations and explorations, interrogations of each other’s work and where each artist wants to take the work next. I would be a quiet participant, occasionally asking questions but mostly hungrily soaking in all that pours forth. Listening and reveling in and enjoying the sharing across generations, all while the sun sets, twilight deepens, fireflies emerge, candles are lit, and the conversations continue into the wee hours of the morning. If only it were so!

Patricia Moss-Vreeland: I first met Vermeer at the Metropolitan Museum of Art during one of my visits on my way home from school. His small canvases always contained everything for me. The light, the intimacy, the brushwork, and the female figure captured so honestly in each daily routine. If we had the chance to meet, I would ask him why he chose to paint on a smaller scale than his contemporaries, and query him about his attention to the female character not as an object under the male gaze but as a “she” engaged in simple activities, whether it’s writing a letter or making lace. Did he find comfort creating these interiors, did he feel they were necessary to document, did they address his inner feelings about women and home, and how did he use a camera obscura, if at all?

My mind then wandered to female painters I’ve admired from the past, and I decided to add to my table Rosa Bonheur, whose painting The Horse Fair was

another at the Met that captured my attention as a teenager. Since there were very few paintings by women in the museum, the work not only overwhelmed me in a great way, but offered a contrast to my treasured Vermeer. Why wasn’t she represented in the iconic art history survey by H.W. Jansen (nor were any other women artists for that matter)? Eventually I read how she would dress like a man to go out into the fields to study animals. I had so many questions about her daily routines and her challenges. With both these artists, I would share with them how much they’ve inspired me for decades, and how grateful I’ve been to have them as my constant companions in making art.

Pamela Blum: I want to talk to artists who pose the best questions, the ones with difficult, ambiguous, multifaceted (if any) answers. When I was a beginning art student, I spent a weekend working on a 12-by-12-foot design project. The instructor, Rackstraw Downes, commented, “It doesn’t need to be that big. It doesn’t need to be at all.” Essentially, he was asking, “What needs to be?”—a profound question, and then, “How big?” Those two questions always form my search for what to say and how to say it.

Downes also remarked, in a drawing class, “Maybe someday you’ll find something to do with that nervous little line of yours.” I screwed up my courage. “What should I do?” “Look at Van Gogh,” he said. And so, I uncovered a search for structure and the relationships among all things.

More recently, I had a chance to ask my current favorite living artist, Hiroyuki Hamada, what he looks for when he makes art and what he looks for in others’ art. He replied, “Authenticity.” Again, no clear answer. And so, every time I look at an image I ask myself, “Is this work authentic? Why?”

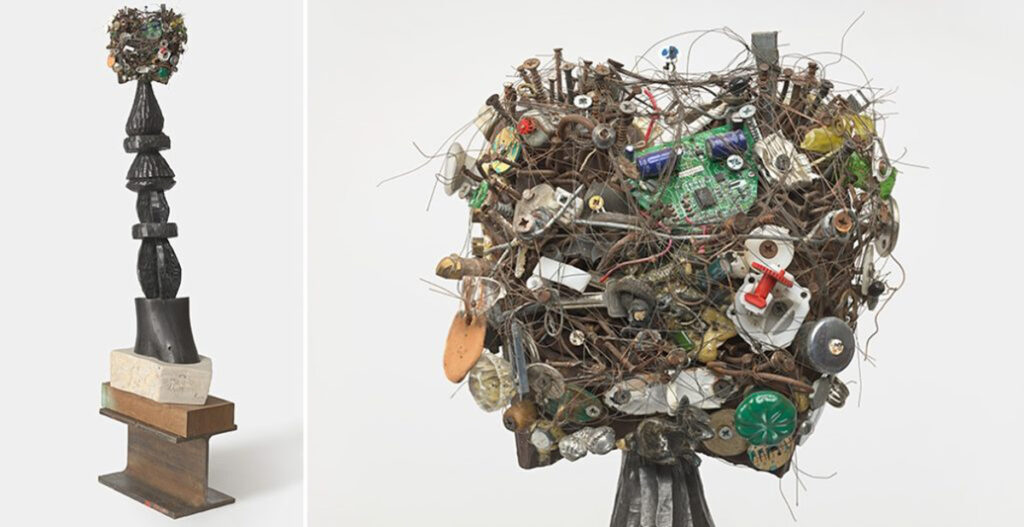

Top: A guest at Christine Aaron’s table, Chiharu Shiota, Sleeping Is Like Death

This was such a fun thing to imagine. I loved reading everyone’s versions. Particularly enjoyed Christopher Benson’s….as it came to vivid life before my eyes.