“I always liked the physicality of sculpture,” says Arlene Rush, who grew up in the Bronx and Queens and now lives and work in what denizens of the outer boroughs still refer to as “the city”—Manhattan. The daughter of Depression-era parents, the second generation in this country from Poland, she remembers playing with Erector sets and Play-Doh, carving soap, and dressing up her twin brother “like a girl” (there were no lingering psychological after-effects). She was a tomboy who loved to play sports and box with her father—“but I also wore my dresses,” she says.

“Family life was great,” Rush continues. “It was okay being female and strong. I was told that you could do whatever you wanted. My father was extremely respectful and kind.” It wasn’t till later in life that Rush ran into gender prejudice and the obstacles almost every female artist of a certain age encounters. “At Queens College, there were no women professors teaching sculpture in the art department, and sculpture was what I wanted to do,” she recalls.

Not surprisingly, gender issues still continue to engage her, and she has examined the many ways sculpture can best express her ends, using many different mediums—from steel and other metals to resin, polyurethane, fabric, glass, found materials, and cement.

After graduation, Rush worked in the design industry for several years because it seemed a “good way to use my creativity along with making money.” By the time she was 29, though, she’d saved up enough to turn to sculpture full time, making works that were formally daring and slyly allusive (one piece called Family Gathering has pipe clamps that look like a pair of handcuffs attached to a long chain).

“I was showing a lot—with galleries, not-for-profits, the Alternative Museum, and the Sculpture Center,” she recalls. “Then in 1987 I was taken on by the Center for Emerging Visual Artists in Philadelphia. They helped launch artists’ careers, and they also sent me to Spain, to Barcelona on a sponsorship.

Liberation (1998-2001), resin, fiberglass, acrylic, ferric nitrate and cement, 27 h by 17 w by 14 inches deep

“The year I really started taking myself seriously,” Rush continues, “the market crashed. A year later, in 1988, I changed my resume to read ‘A Rush’ because the art world was still so male-dominated and a female artist was looked upon differently.”

In the early ‘90s the artist became a dedicated student of Buddhism and moved away from the largely abstract vocabulary that characterized her sculptures in metal. “My practice has a lot to do with how one looks at life, with perception, and what we all as human beings share—not just looking at ourselves individually, but looking outward and inward.”

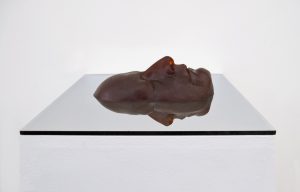

Among her ongoing projects has been a series of heads cast from her own features but intended as a kind of universal head. The exercise has to do, she says, with “stripping away the things that make us different from other people.” And the life casting itself, as she explains “is not a very pleasant process.”

Reflection of the Self III (2011), polyurethane, rubber, and two-way mirror, 48 h by 12 w by 12 inches deep

She works with a casting studio, and starts by putting her hair up in a cap and slathering Vaseline on her head. “They close up your ears, so that you feel like you’re underwater. Then they apply Alginate—the same stuff dentists use to take an impression of teeth—and secure it with a plaster bandage.” From that a mold can be made of an androgynous head, which Rush has used in a myriad of ways, some of them referencing Buddhist practice and bearing titles such as Exchanging Self with Others, Beginner’s Mind, Reflection of the Self, and Meditation 101

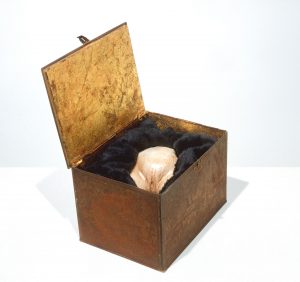

Since the late ‘90s, the artist has started working “much more conceptually.” She’s tackled gender issues, but in a light-hearted and often sensuous way. The Box from 1998, which kicks off her “Vaginal” series, shows a mold of Rush’s own “lady parts” nestled in fake fur inside a box of rusted steel and metal leaf. “It’s about how men look at women as an object,” she says. “I wanted it to be precious but also falling apart.” Other examples from the series are more opulent, realized in dazzling colors and finishes, and often sprouting vegetative tendrils that could suggest both penetration and fertility.

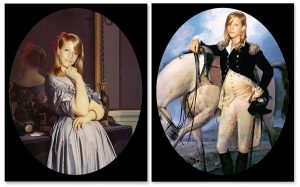

The last couple of decades have been exceptionally productive ones for Rush. She has examined the peculiarities of twinship in a series of photos that take on family memories, pop culture (Barbie and Willie dolls), and masterworks of art history. She has worked with casting different body parts, made photos inspired by a bout with breast cancer, and contributed installations commemorating the fortieth anniversary of Ntozake Shange’s choreogram “for colored girls who have considered suicide when the rainbow is enuf.”

But perhaps her most ambitious recent series has been documenting an artistic life that, like many, has suffered its share of rejections and setbacks. “Evidence of Being” started when Rush embarked on a project to archive the objects accumulated over the course of a 30-year career. A couple of multidisciplinary installations incorporate shredded rejection letters contained inside glass vessels reminiscent of funeral urns. A series of gilded envelopes, dripping with resin, commemorates the rejections from some of New York’s top galleries: Cheim & Read, Grace Borgenicht, Andre Emmerich, et al. (more on this in “You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me,” about how artists handle rejection).

As she notes on her website: “By looking historically at the practical conditions that artists face: high rents, limited space, the art market, gentrification, class warfare, gender bias, other kinds of discrimination and the market-based metrics of success, I found these objects became more than the surplus of my practice; they became a lens through which these issues could be explored.”

The various elements of the series, which have yet to find a home, says much about an artist’s life in New York City during the past few decades, but Rush approaches the summing-up in a typically wry fashion (calling one installation, for example, Making Lemons into Lemonade).

“When you think about what it is to be an artist—what do you do with all the things you save, for instance?” she asks. “It was pretty major to examine all of this, and it became important historically for me. I’m now working across the street from my first studio, which means I’ve been in the same neighborhood for more than two decades, and that is almost unheard-of in New York. It says a lot—how does one survive? How does one do it?”

Ann Landi

Top: Untitled Vaginal Installation (2006-2015), resin, fiberglass, oil, ink marker, and acrylic, dimensions variable

Terrific article. Arlene deserves a retrospective in a museum. She may have to wait until she is 101. Keep going Arlene…your work is appreciated by other artists who know!

Thank you For this article about Arlene and her work. Extraordinary woman and engaging politically stimulating work.

Brava!

Nice to read about this recognition of your work

Love Arlene! Her work deserves a museum show. Arlene’s conceptual artwork on rejections can serve as a therapeutic shrine for many. Happy to know Arlene personally and hope to learn from her. Thank you for the article.

Thank you all!!. Really touching and inspiring. So appreciate all your support and encouragement. I think I will use these in the lemonade part of rejections. oxoxo

A great presentation. Congratulations on your new website and the clear explanation of your work.

Keep on growing . Love your latest work.