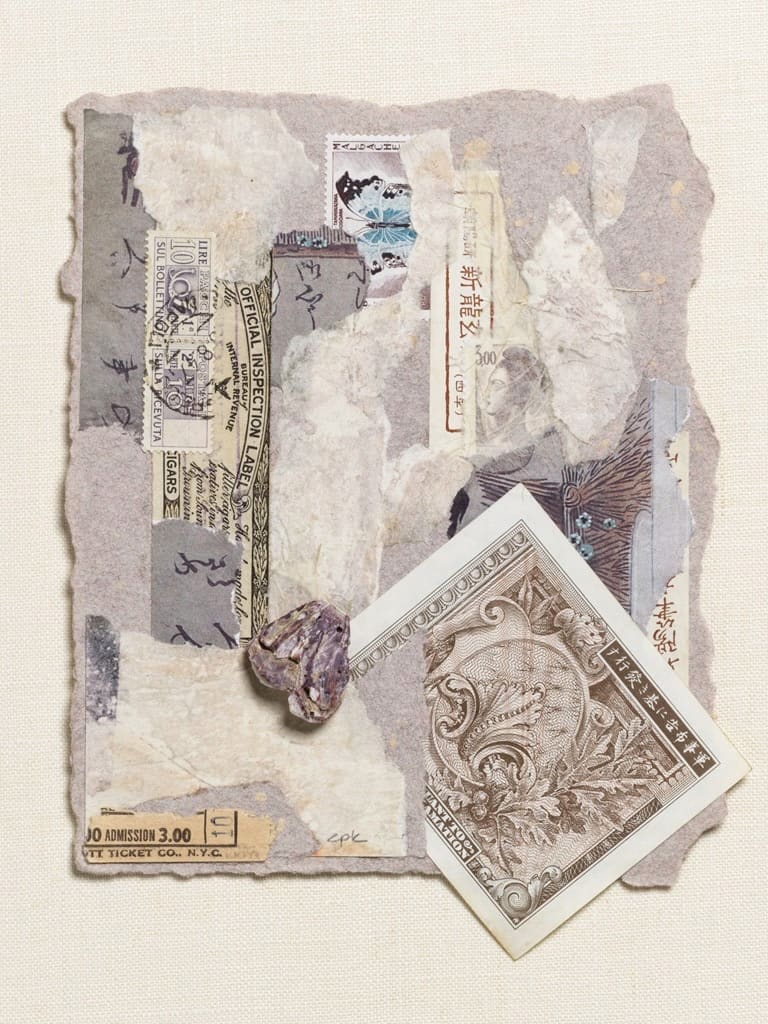

Nara Ehon (1990), postage stamps, found papers, handmade papers, currency, barnacle fragment, 7 by 5.5 by .5 inches

A strong interest in craftsmanship underlies Carole Kunstadt’s quirky sculptures and two-dimensional works, and though her career has taken a few detours over the years, she has maintained a respect for materials and execution, even as she is tearing apart old books to make magical objects that pay homage to earlier times and trailblazers.

Kunstadt grew up in Sharon, MA, a small town outside of Boston, and describes herself as being “forever interested in art.” Her parents—a dental hygienist and an orthodontist who met and married in New York—encouraged the artistic talents of their two daughters, and, she claims, “We were never idle. We were always drawing, painting and making things—embroidering, sewing, and later macramé. Art was central to what we did.”

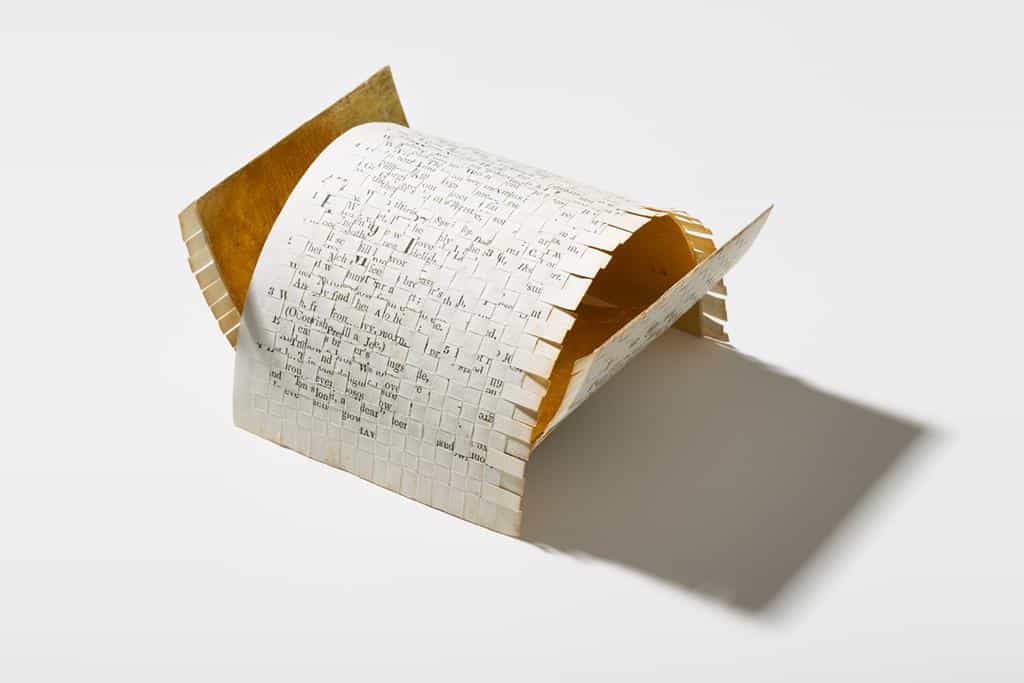

Five Books of Moses (2009), gampi tissue, 24-kt gold leaf, paper: Old Testament pages, 1904, 8.5 by 11 by 4 inches

She recalls an art teacher who lived up the street and opened her house to a few kids for after-school classes. “She had a Revolutionary-era home, filled with antiques and collectibles, and from this menagerie we could pick whatever we wanted to draw or paint. At the time, that was a pretty forward-thinking attitude—that a child could choose the subject matter and the media.”

During high school, Saturdays were spent in classes at the Mass College of Art and the Boston Museum School, where she placed in junior and senior award programs. For college, Kunstadt studied at the Hartford Art School in Hartford, CT. In the early 1970s, the BFA program was fairly traditional. One of her more memorable teachers was Rudolph Zallinger, whose principal claim to fame was a 110-foot-long mural called The Age of Reptiles, painted for the east wall of Yale Peabody Museum’s Great Hall in late 1940s. “He taught us egg-tempera painting according to 15th century principles,” the artist recalls. “I also learned from him how to upscale designs with grids, to make them larger than the original as the Renaissance painters had done.” At the same time, she had independent study with a landscape painter, Paul Zimmerman, who valued the creative impulse as much as the execution and the final creation. “His emphasis was on how much enthusiasm and passion you brought to your projects.

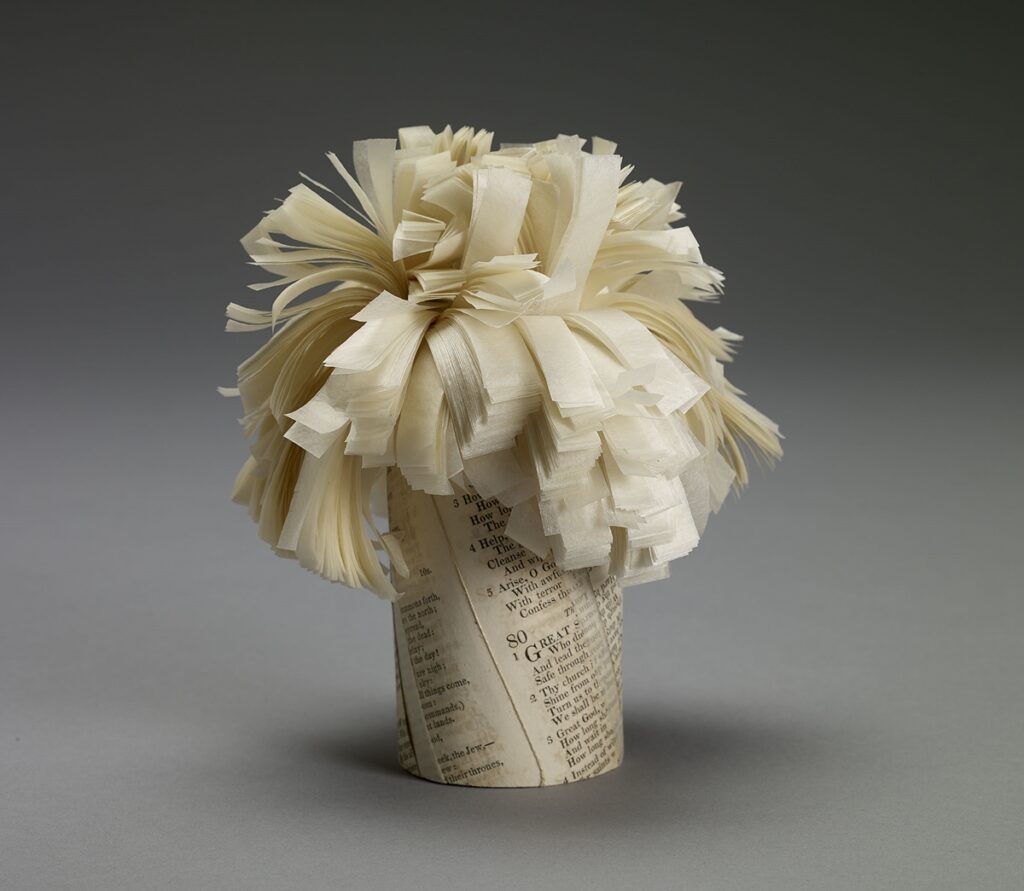

Sacred Poem LXXXIX (2014), 24-kt gold leaf, interfacing, paper from the Parish Psalmody,1849, 5 by 6.5 by 2.5 inches

“That stands true for me today,” she adds. “I can be very detailed about what I do, but I need to be connected to the works in an emotional way.”

Kunstadt got married at 21 to a student from Yale and moved to Los Angeles so that her husband, Robert, could attend UCLA School of Law. She continued taking classes at UCLA and had a studio in Art/West Fine Art Center, with 12 other artists. “It was a supportive creative community, showing together, hanging out together.” Though L.A. at the time was a hotbed of artistic activity—the California Light and Space Movement was still in force and Judy Chicago had launched the Feminist Art Program at Fresno State College—Kunstadt remained unmoved by the prevailing trends. She was drawing and making fabric constructions, layered and stretched on a frame, which then led to what she calls “an incredible detour into investigating woven tapestry designs.”

Ovum II: Homage to Margaret Fuller (2016), fractured ostrich egg, linen thread, twigs, paper (pages by Margaret Fuller,1855), 5.75 by 10.5 by 8.5 inches

After her husband graduated from law school in 1975, the couple moved to Munich so that Robert could pursue a fellowship in International Trademark and Copyright Law. Carole studied tapestry design at the Akademie der Bildenen Künste. In the two and half years they spent in Europe, she says, “I was constantly looking at art as well as all the tapestries I could come across. I never did an MFA, but I felt like living in Europe, traveling to see everything I could, was the best imaginable kind of graduate study.”

Pressing On: Homage to Hannah More (2018), 20 -inch circular grouping of antique sad irons, scorched lace and paper: pages by Hannah More, 1791

When they returned to the States, they settled in New York City, and Kunstadt contacted a weaver she’d read about, Helena Hernmarck, whose tapestries she admired and who lived and worked in a loft in SoHo. Hernmarck by then was known for monumental works using photographs as a basis for her designs and had enjoyed solo exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. A year later, the Swedish-born artist reached out to Kunstadt and hired her as an assistant. “This was in 1979, in SoHo, but it was not the high-end shopping district it is now,” she recalls. “I started working for her from the very bottom on up, which could mean anything from feeding the cat to making lunch and assisting in weaving production.

After a few years, Kunstadt and a partner started their own tapestry workshop in the back of an architect’s office in Chelsea. The business enjoyed a serious boost after they connected with Gloria F. Ross, the sister of Helen Frankenthaler, who brought the European tradition to the U.S. by matching weavers with artists’ work to execute in tapestry. The young weavers—Kunstadt was barely 30—landed a commission to work with Frankenthaler, one of the leading lights of American painting since the 1950s. “We had her painting This Day in our studio so that we could reference it directly,” she recalls. The project was fairly modest in size, about five by seven feet, but Kunstadt was pregnant with her first child and felt physically challenged to do the demanding work on the loom.

Ovum XXVII: Homage to Margaret Fuller (2020), antique coal miner’s wooden canary cage, feathers, wooden eggs, paper, pages by Margaret Fuller,1855, 6.25 by 5 by 6.25 inches

Intuitively, she also felt that this wasn’t really making the best use of her talents. “You can work on something for months and months, even years, and until the final ‘reveal,’ you don’t truly know what it will look like.”

While raising her kids on the Upper West Side (a second son arrived in 1986), Kunstadt worked as a freelance interior decorator but continued to pursue her own muse—drawing, painting and making collages. “The accumulated ephemera of my life started to appear in my work—receipts, tickets, stamps and found natural objects such as feathers, which I then combined with handmade papers. A small but inspiring exhibition of Anne Ryan collages at the Met was an early influence.” But it wasn’t until 2006 that the artist chanced on the methods and materials that have sustained her up to the present. She found a collection of psalms and hymns for public worship, published in 1844, in a used bookstore for about $25 and worked with its pages for three years. “I used it up and then searched online to get a second volume. Even though it was the same title, it was different. The resulting work was both additive and reductive, as I was moving into weaving and gilding and layering. The material qualities of the second book pushed me into doing more sculptural pieces.”

Out of the contents of those two books the artist realized 106 pieces, and ever since then she has used books. The pages end up incorporated into different series with evocative names, such as “Ovum,” featuring egg-like shapes, shoe lasts, and baskets realized from bits of text. Or “Pressing On,” which pairs “sad irons” (old-fashioned flat irons) with fur, lace, and more snippets of text. As one critic noted, “In Kunstadt’s hands, books are broken down and transformed, phoenix-like, into new shapes that encompass the original meaning of the words while transcending them. The re-purposed forms reveal a previously undisclosed essence within the books. They also create new stories out of the antique objects, unlocking the physical potential latent in the pages.”

Sacred Poem XXX (2017), gampi tissue, thread, gold leaf, paper from the Parish Psalmody dated 1844, 7 by 7 by 7 inches

Most recently a feminist edge made its way into the work after she bought Woman in the 19th Century, a book by Margaret Fuller, the first great female intellectual in American letters. To date, she’s still using it as material.

Kunstadt’s projects of the last few years have brought together a number of different talents and impulses, which run from her early experiences with embroidery and sewing through her adventures in weaving up to her recent fascination with the book as raw material. “I went through a long gestation period,” she notes. But the efforts have paid off with inclusion in shows at the Museum of Arts and Design and the Museum of Biblical Arts (now closed), both in New York and works placed in the Permanent Book Arts Collections of the National Museum of Women Artists, Center for Book Arts, Bowdoin College, and Baylor University. She exhibits regularly throughout the Hudson Valley, to which she and her husband moved seven years ago. The region has proved to be a rich source of material and inspiration. It was far easier to track down the sad irons used in “Pressing On,” and to date she has rounded up 108. “Having grown up in New England, I’ve discovered similarities and feel a familiarity with the region,” Kunstadt says. “It’s all about the the solitude, the underlying importance of history, and the immediacy of Nature.“

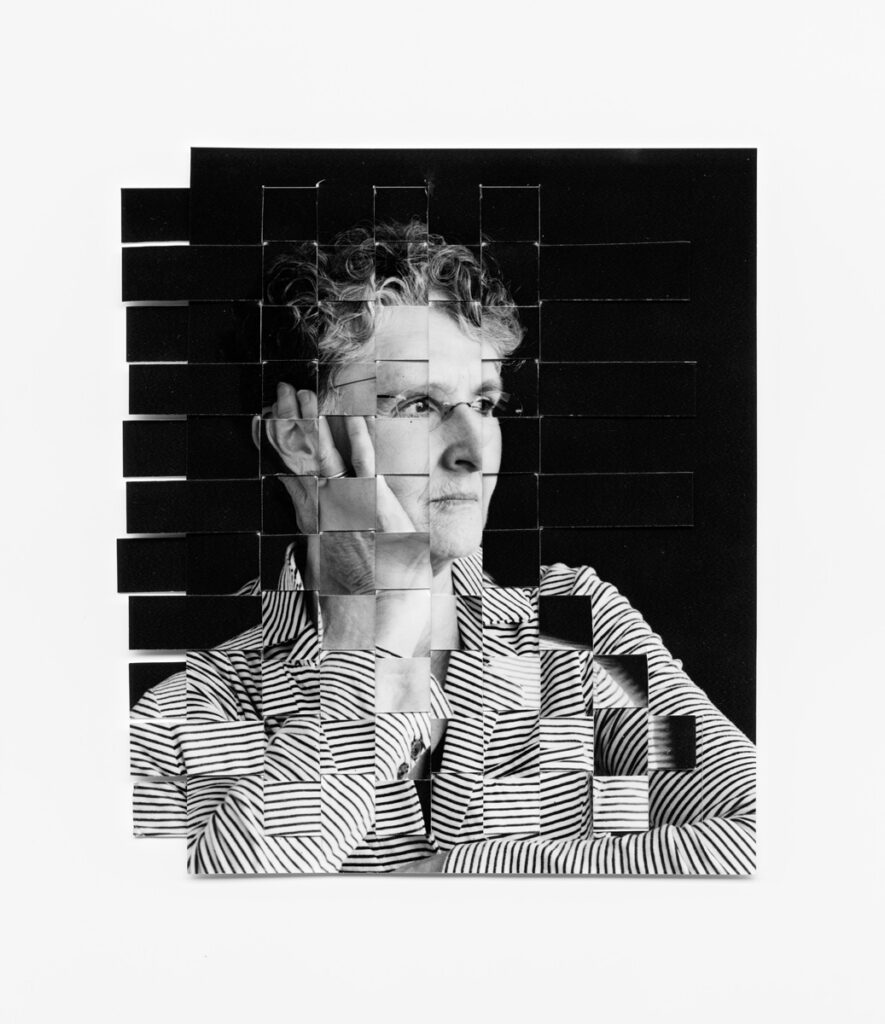

Carole Kunstadt, a portrait made in collaboration with her son, Kevin Kunstadt, a photographer in Brooklyn, NY.

Top: installation shot from “Pressing On,” a solo show at the Woodstock Artists Association and Museum, Woodstock, NY, 2018, including 86 “sad irons” on a table by Elizabeth M. Fraser, made in 1920

A wonderful account of an art filled life. I admire you, your life and your work. It is too bad that we are so many miles apart.

I’m a collector of Carole’s art . For me and those that view it, it’s ageless. I never get tried of it. Its delicate valence inspires me, with all its hidden meanings.

Carry on Carole, I’m sure there’s much more to come.

❤️ Frank DeCrescenzo