In looking over the images from Part One of this post, and from those below, it occurred to me how often art made from found objects and random detritus has a childlike quality about it, even though the trained eye knows there’s a sophisticated vision behind the impulse to see how unlikely elements might act in concert. To bring up Picasso again, this observation from the master seems especially astute: “Every child is an artist. The problem is how to remain an artist once he grows up.” Which makes me wonder if the impetus to recycle begins early. Kids will take orange-juice containers to make walkie-talkies or gather leaves and twigs to make a play forest. Popsicle sticks, boxes, and straws often prove potent triggers to the imagination. Our earliest “artistic” efforts, in fact, may include all kinds of stuff we run across pawing through drawers or poking in wastebaskets. I vividly recall making a pin cushion for my mom one Mother’s Day from one of the cone-shaped falsies I found in her lingerie drawer (this was in the early 1960s, before women started to reject such accoutrements). The satiny cream-colored fabric made a perfect Cinderella-type skirt and a few pipe cleaners finished off the body and head. All I can recall of Mom’s reaction is that she had the good grace not to laugh or blush when I presented the gift on her tray for breakfast in bed.

Yet laughter and surprise are part of the fun of successfully recycling unusual bits and pieces not normally considered the stuff of art making. Chris Victor uses toy parts, CD cases, wax candles, and other ephemera to create buoyant installations where the whole speaks louder than the parts. Allan Rosenbaum finds magic in old neckties and fabric scraps. And tin cans offer Allan Rubin a way of recycling both throwaway items and Old Master paintings. “Really there is no such thing as waste,” observes Candace Compton Pappas. “We and everything known to us just keeps cycling on through this endless circle of life and decay and death and transformation.”

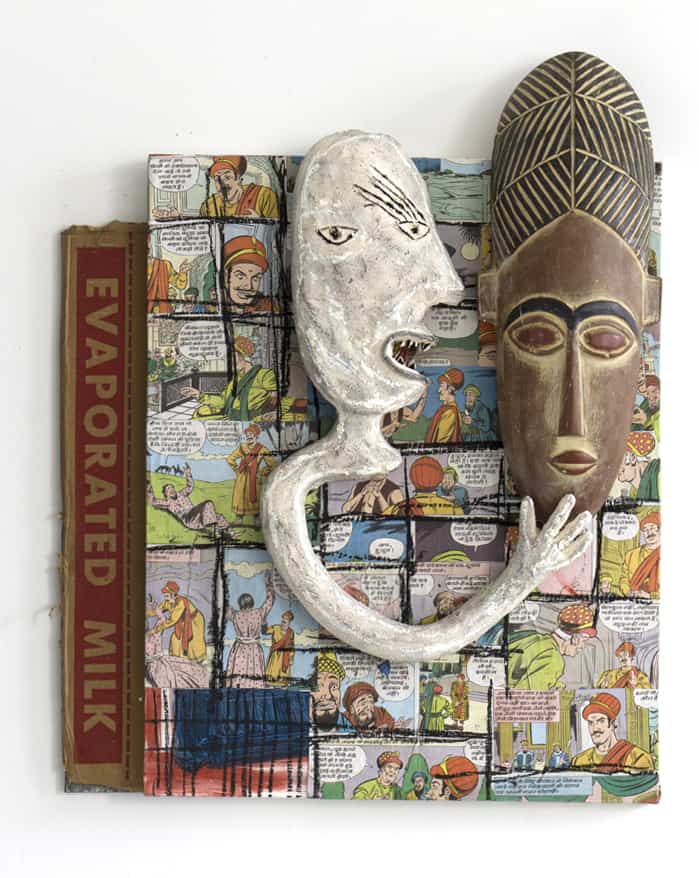

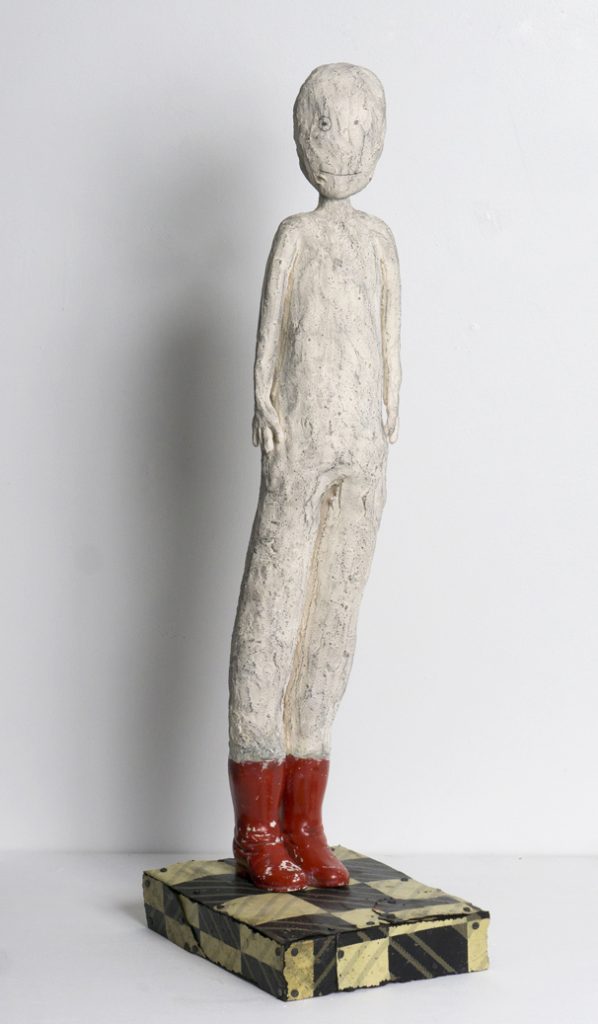

Melissa Stern: It really isn’t a surprise that I have ended up making art with found objects. I have collected things since I was a teenager. I was fascinated by things that I found in junk shops and flea markets. I’d take my babysitting money and buy old toys, vintage children’s books, Victorian buttons—whatever struck my fancy. I have always loved objects and the inherent power that they can contain. I schlepped boxes around with me as I moved throughout my younger life, occasionally shedding things (what did happen to that box of patent-leather prom shoes?), and of course everything that I lost or let go of I wish I still had because I now see how they could be vital parts of my sculptures.

I love the technical and conceptual challenge of working with disparate materials. The combination of the figures that I fabricate and the object that they relate to and are connected to makes for an interesting tension that I suppose is a part of my artistic worldview. Recently I’ve become quite interested in souvenirs—the objects that people buy to remind them of experience. The psychological connection between object and memory is an ongoing fascination of mine. My request to friends for donations of unwanted and unloved souvenirs has resulted in an avalanche of objects—bits and pieces of other people’s memories and experiences that I am in the process of incorporating into my new pieces.

Candace Compton Pappas: I have always integrated “found” things into just about everything I do, even as a kid. I recently have been wondering where this concept of “waste” came from—a necessary concept for dealing with things that that get in our way? Or fill our coffers, closets yards, skies, vistas, whatever. Really there is no such thing as waste—we and everything known to us just keeps cycling on through this endless circle of life and decay and death and transformation. Round and round. So we put things in the ground (dumps), we incinerate our bodies, we fill our heavy double-strength plastic garbage bags, we donate to those in need. Nothing goes away. Everything transforms. So I pick things up, things I notice, and I like to give them a place of honor. As you can see my assemblages are really little altars. We all deserve space and love, and how I love to make these spaces.

Trio (2019), cement molded base, bottle caps, shells from the sea and swamp, Christmas ornament, burrs, lime juice and perfume bottle, 16 by 9 by 4 inches

Altar to Finds IV (2019), molded cement base, found starling, rabbit fur and feet, tin can, and plastic frog, 14 by 12 by 12 inches

Gina Telcocci: I use all kinds of stuff that is “harvested” from out in the world, from roots and seedpods to found broken apparatus to wreckage washed up onshore Because I am a scavenger by nature, I’m always scanning the area around me during my wanderings in the world, for shapes, colors, lines, and textures that appeal. There is a little nostalgia in my love of old, well-made things, and in how they wear over time. But it is deeper than that. Even the simplest human-made tools are an expression of human ingeniousness (creativity), which I think of as a spark of the divine. And the eroding of surfaces, the patinas of aging are eloquent reminders of the ineffable nature of time and the temporality of our worlds. The initial impetus in this direction? Picking up debris, dragging junk home because I loved the shape of something or the beautiful patina on a surface. This really started in earnest when I discovered dozens of discarded clay cone pads in the ceramics yard at my graduate art department. I had set out to make cast replicas of organic forms, in order to create an installation using multiples of the same form. But the variations of color and texture in these found objects that were similarly shaped was so much more interesting than exact replicas of one form; it set me on a path of collecting multiples rather than making multiples.

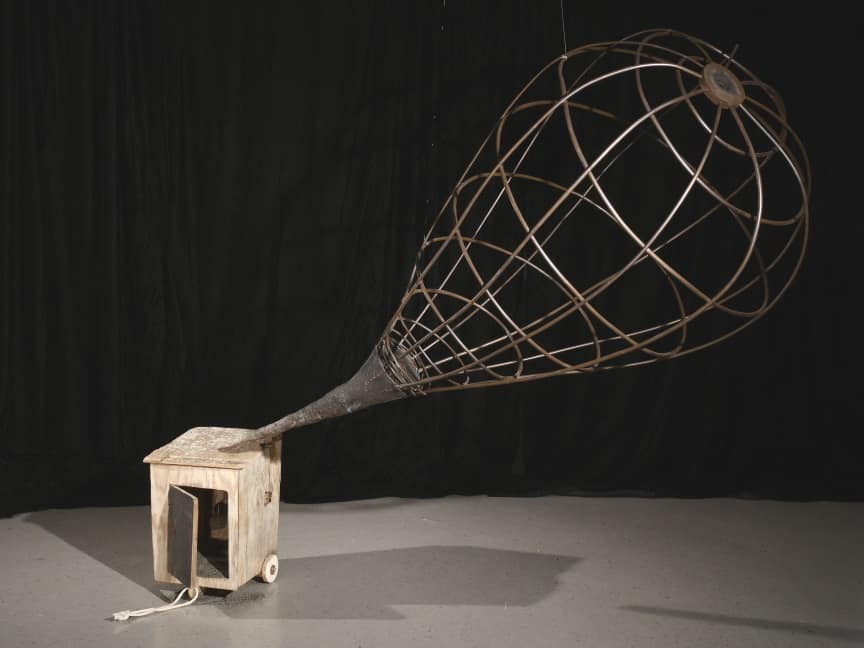

Gasp (2017), rattan, plaster, drift-ply, mixed media; 68 by 33 by 16 inches; paired with Gasper’s Shack (2017), found wood, mixed media, 18.3 by 13.5 by 15 inches

Allan Rubin: Three and a half years ago I began a series of painted sculptures made from recycled metal food cans. I sought to represent art heroes who influenced my work and called the series “Canon” (pun intended). I reinterpret and recycle self-portrait paintings of well-known and some lesser-known master painters, in their own style, in three dimensions, in the novel medium of using recycled metal cans from my kitchen or donated by friends and restaurants. I bend and hammer the metal, then screw the pieces together, adding noses, ears, etc. Then I prime and paint the constructions in oil. After matching the frontal view, I must invent the reverse to complete the painted sculpture in the round. I am excited by the tension of the illusion of the paint upon the still visible substrate of the recognizable metal cans. It is my goal to have a nearly equal number of female and male artists portrayed and to include artists from non-Western genres. An Internet search has found no other artist working with this method, so I am confident that I have found a unique niche of expression to enjoy exploring toward unknown revelations.

Canon-Albrecht Dürer (2018), oil on metal cans and mailbox, 20 by 20 by 12

Albrecht Dürer, self-portrait (1500)

Canon-Anonymous 2019 oil on metal cans h 22 w 14 d 21″

Anonymous, 17th-century Bolognese woman painter

Amelia Currier: This fall I had the opportunity to spend ten days in the warehouse district of Paris, for an artist retreat. My enchantment with the City of Light is such that even the detritus is precious. Every evening I walked the streets of my quartier, breathing in the cool breeze off the river, scanning the curbstones. I have been scouring sidewalks and the bare earth for years on the prowl for the discarded. Often these tossed bits reveal a story. For example, the center drawing in my collage is a thoughtfully rendered diagram of the young artist’s home. The artist has included each knob on the stove and even a delicate hook to hang one’s washcloth on. The crooked stairs are impossible to climb—just as it is impossible for me to glean the love and effort this child devoted to the drawing.

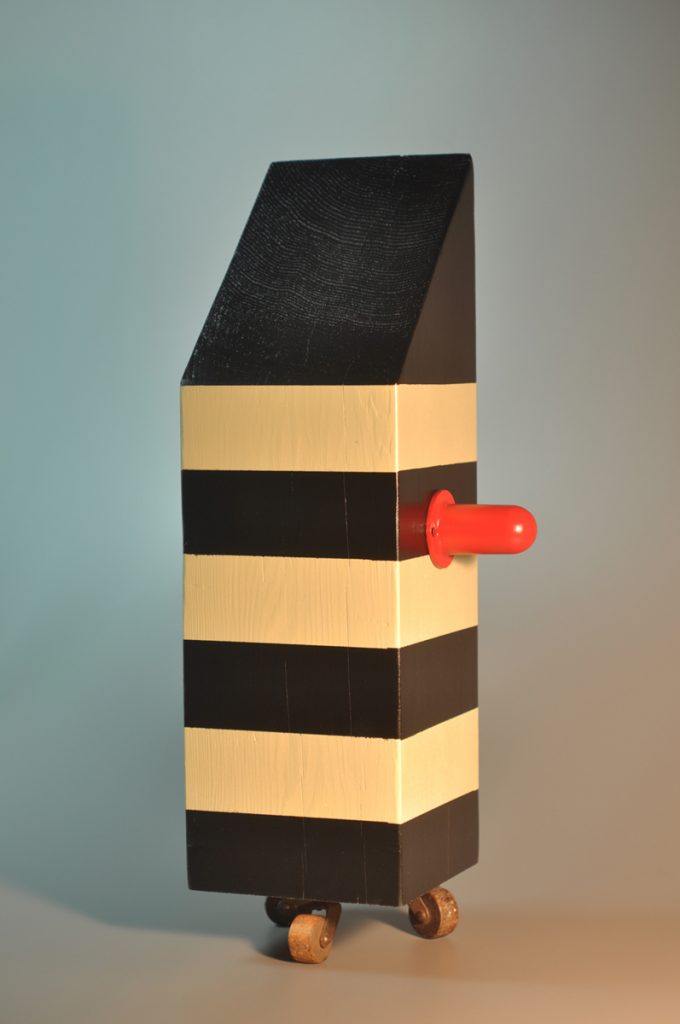

Soothe the Beast, a more sculptural work, is composed of 130-year-old barn wood that I have charred, scraped, and stained. The element in the forefront is a reworked remnant from a toy boat. This piece, so rich in its historical provenance, has now become an instrument of meditation and selfhood.

Chris Victor: I use post-consumer recyclables and other found materials in my work. I think of myself as materially omnivorous. Not that I really am, but I want to feel wide open and not limited. I like to go into the studio knowing that anything can happen, and these materials support that. Their availability, familiarity and everyday qualities allow the viewer a way into the work, and allows me a sense of freedom to explore during the making. They inspire a spirit of making-do and jury-rigging that is at the heart of my sensibilities as an artist. The environmental benefit is a nice plus but that isn’t part of the draw at all for me. I like to use materials for what they do well, and discovering that is a large part of the process. I’m repeatedly surprised how one material can feel totally dead and useless one day only to be vibrant and interesting another. The change was in me and my way of seeing, not in the material at all. This is why my studio is filled with stuff; I never know what will resonate next!

Work in Progress for “Patterns of Engagement” at the Albany International Airport, Concourse B, winter 2020

Victor’s final untitled installation includes found co-axial cable, assorted plastic game and toy parts, model car parts, wax candles, found airport signage, plastic CD cases, colored pencils, broom handle, plywood, acrylic paint, found wooden spoons, cardboard packaging, plastic packaging, 144 by 160 by 180 inches

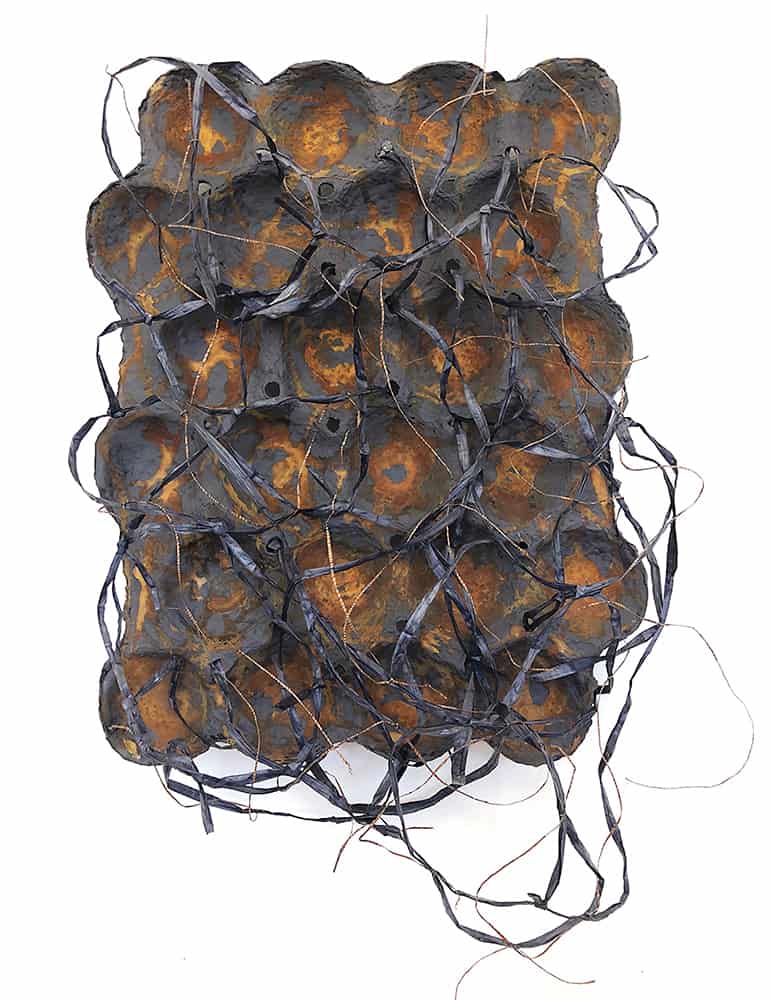

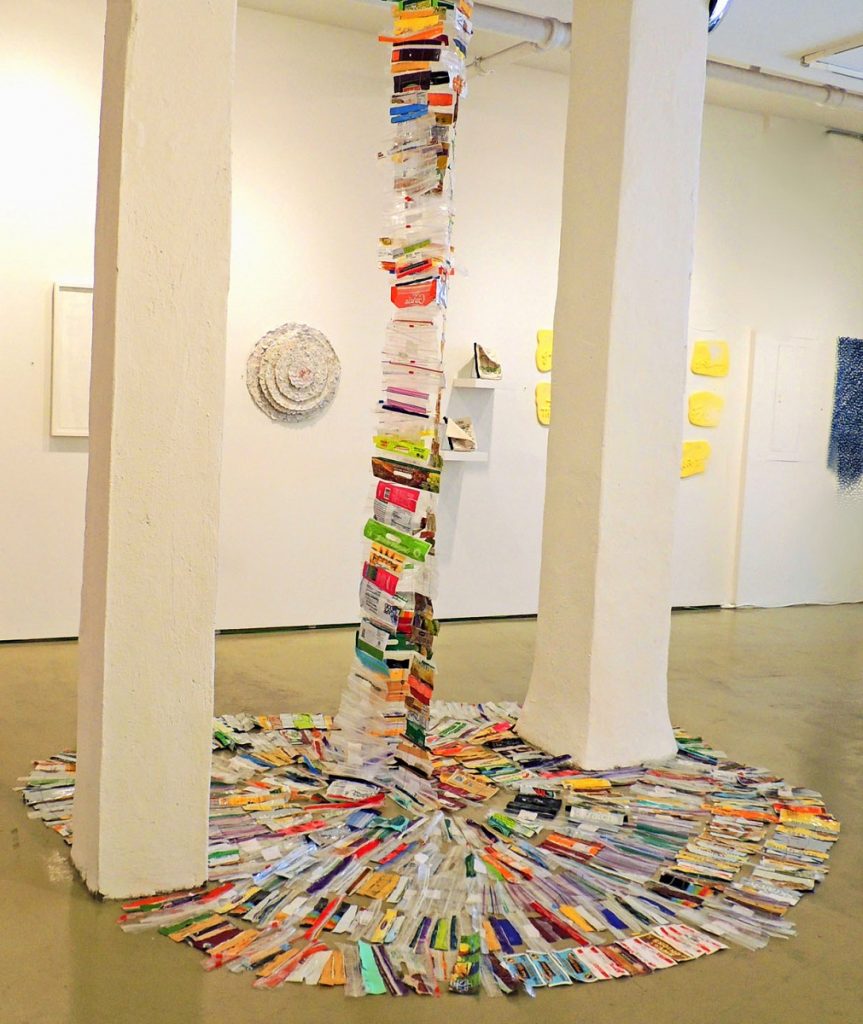

Lia Rothstein: I have collected old packaging materials for years, attracted by their shapes, textures, structures, purposes, and sense of history. The intrinsic beauty, durability, and malleability of these humble “disposable” materials is increasingly inspiring to me in my recent work focused on memory, memory loss, and aging. Surfaces that are worn but not quite worn-out, changed through age and exposure but still, at least minimally, functional, and those that are corroded but hardened and protected by patination. The fragility and ephemeral nature of our bodies as we age and of our very planet are weighing on my mind as well (my mother suffers from dementia). With the proliferation of cardboard materials, because of so much online shopping (what some writers have called our increasing “cardboard footprint”), upcycling and repurposing some of these intriguing materials is important to me.

Mimi Graminski: Recycling is in my blood. As a child, I recall watching my Sicilian grandfather collect each little piece of string and wire that came into his small grocery store. He saved the seeds from peppers, melons and other fruits to plant in his vegetable garden. I went to junkyards with my father to help search for spare parts to use in fixing farm equipment. He would use the parts as is, or cut, weld and redesign them to make a tractor or plow run again. This history, combined with my concern for the environment, has led me to strive for a zero-waste lifestyle. All contribute to my artistic practice which is rooted in the exploration of materials, memory and identity. I accumulate dozens of cotton bags that once contained rice and feel drawn to use them—sewing them together into an oversize wall “tunic.” I realize red, orange, and yellow plastic mesh fruit bags will go into the waste stream, so instead I connect them into large quilt-like forms. I collect tubular cellophane bags (packaging from rice cakes) and pin them to the wall to create a room-size installation incorporating light and shadow. I learned I could recycle plastic bags but had to remove the zip locks first. I collected them (mine and a neighbor’s) and stitched hundreds together into bolts of zip-lock ‘fabric’. Together they grew into the installation “Extra Value.” (The title comes from the bold yellow letters on baking soda packaging, which seemed to sum up the worlds of advertising, excess, and capitalism.) Each recycled element carries its original purpose into the installation, adding layers of meaning and expanding on the identity of the whole.

Cindy Blakeslee: My art primarily arises from the inspiration of that which is abandoned by my fellow homo sapiens: materials cast off are caught, mid-air, to be reformed into something of beauty or perhaps simply an almost unrecognizable restatement of itself. To me something, almost anything, is more valuable if it contains or issues from the reuse of materials deemed useless by others. Thus my art is a subliminal (or perhaps not so) political statement which I hope will seep into the consciousness (or even unconsciousness) of those who admire its form, function, humor or beauty. It’s also just plain fun to make and to look at. Occasionally I break the rules and use virgin materials, but only occasionally and with great guilt. I am all about form and texture produced in different ways and with different (and often disparate) materials. This collection of sculptures contains myriad found objects: VCR tape, copper, nails, post/beam scraps, horsehair, musical instruments, maps, plywood scraps, tools and other cast-offs. I am an autodidact and a late bloomer, having been many things other than an artist over the years. The consistent motivator is that I have been a very active environmentalist for more than and that world view feeds (actually dictates) my work with found objects.

Beth O’Grady: My use of upcycled materials is a statement about the fragility of the environment. Why should my artwork be archival, and why should I use new and expensive supplies, when there is mass extinction and unchecked climate change? Corrugated cardboard boxes are ubiquitous, commonly used for the packaging and shipping of products and, once used, discarded as garbage or recycling. Yet corrugated cardboard boxes can provide rich material for artistic experimentation and exploration. An undamaged box, disassembled and cut down at right angles, provides a quiet, smooth expanse of a brown, subtly pre-lined surface, bringing to mind an Agnes Martin painting. I can use a blade and peel away the surface, revealing a three-dimensional lined area underneath, or use the surface to paint or draw on. A dented and torn box, with evidence of the shipping process, labels, staples, packing tape, and product branding, provides many textures and forms that add to the conversation. Sometimes, nothing is required. The box, as it is, is enough. It’s a readymade. Interested in reductive, non-objective art making, I keep my additions or subtractions minimal. Once a piece is finished, I photograph it on a table, or the slanted walls of my attic studio. I am often surprised by what I see. Light, shadow, and architecture interact with, and influence the finished piece.

Suzan Shutan: My work’s core focus is on sustainability issues at the process level. Having grown up playing in woods that became my insular outdoor world and then watching as it turned to landfill for prefab homes, I developed a passionate love for nature: fireflies lighting up the thickness of the dark and caterpillars shedding their furry skins, the growth of fungi and lushness of green moss. I use all kinds of common multipurpose inexpensive materials such as pom poms, straws, string, nails, and tar roofing-paper to create sensually brooding work that speaks to both the destructive nature of our human carbon footprint and the restorative attempts to issue damage control. Colored areas are intentionally enticing and playful, yet are the result of extensive research into harmful toxins leeched into the enviornment from fertilizers, pesticides, detergents, building and household chemicals. The color coding is usually displayed as map keys in which each color is broken down to its chemical compounds, indicating the harmful effects from our daily consumption.

Installation “Becoming” at Zacheta National Gallery, Poland (2014-15), pom poms and wire, dimensions variable

Allan Rosenbaum: This body of work was initially inspired by a desire to repurpose a collection of neckties and fabric scraps that once belonged to members of my family. The scraps, accumulated over decades, were an uncanny memorial—to the time spent on selection, the labor of execution (quilts to clothing), and the memory of use. As the project developed, I realized that the fabrics possessed the power to tell specific stories, but I chose instead to focus on the creation of meaning that would move beyond my personal associations. I utilized online resellers to build an expanded palette of fabric selected from vintage dead stock and estate fabric collections from around the world. I incorporate the palette into works informed by sources that have aroused my curiosity—ranging from tattoos to microscopic photography, the body, and folk-art quilts.

Top: A shot of elements from Chris Victor’s installation, “Patterns of Engagement,” at the Albany International Airport (through March 2, 2020)

I invented recycling for the artist’s scrap paint tube and materials. Dan Cameron states that my claims for inventing two new conceptual arts in visual art history painting are self evident truth. Jade Dellinger Director and Curator of the Bob Rauschenberg Gallery made me part of the Rauschenberg conceptual legacy last July 27th, 2019. I am pioneering the establishment of Civil Rights for visual art, artists and art history based on art history through my 2016 City of Fort Myers, Florida Art and Culture Grant sponsored by the Rauschenberg Foundation. The recognition of new conceptual art or new form in visual art history painting is not allowed in academia . markcranford.com