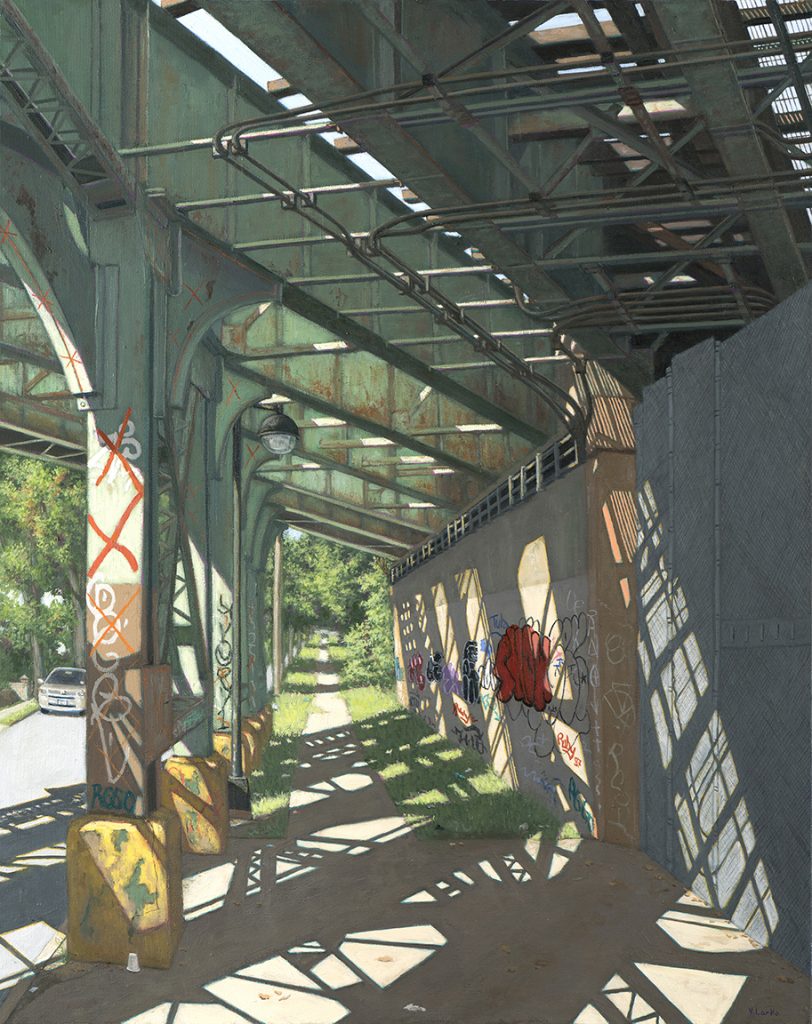

For more than three decades, Valeri Larko has celebrated the strange appeal of some of the most desolate spots around her home and studio. Up until she moved to New Rochelle, NY, her favorite stomping grounds were close to Jersey City, NJ. “The beauty and the grit I encountered there and in the surrounding area grabbed my imagination.” For the last 16 years, her preferred territory has been the Bronx, weed-choked neighborhoods where raucous high-keyed graffiti often covers all available surfaces, from abandoned RVs to the walls of shuttered stores and small businesses. “A lot of the things I paint are on their way out,” she says. “I want to capture them before they’re gone.”

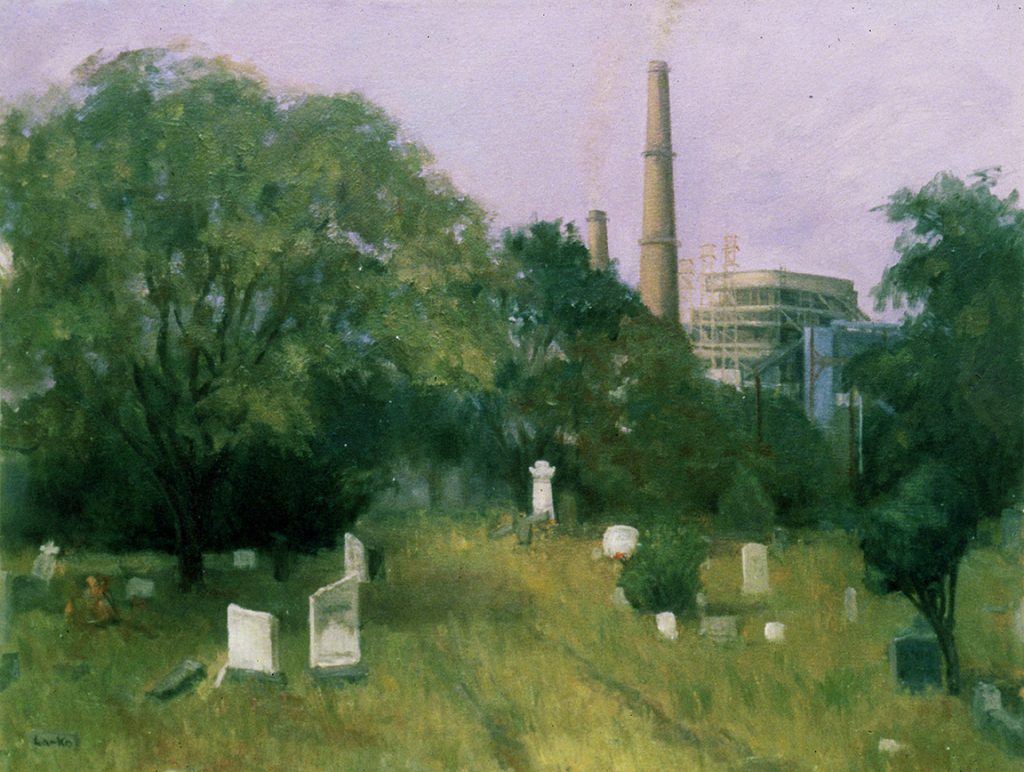

Earlier works—such as a pair of sphere tanks or a glimpse of the Hess Oil Refinery—often had a sleekly Precisionist feel. Others, like the view from a bridge in Jersey City or a cemetery in the shadow of a Budweiser brewery, were moody, almost melancholy testaments to urban wastelands. But in recent years, the tone is upbeat: no matter how derelict the buildings or how peculiar the signage, the scene unfolds in cheerful daylight under brilliant blue skies.

Often Larko injects a slyly humorous note: The billboard behind the Holiday Motel promises “After you die/You will meet God.” A banner for the Romantic Depot advertises “15-minute parking,” while the painting of the store itself beckons with “Sexy Halloween Costumes” on sale and “Plus Size Lingerie.”

Larko grew up not too far her current haunts, in Parsippany, NJ, approximately 30 miles west of Manhattan, in a household where the only real encouragement to pursue art came from an aunt who was an interior designer. “I didn’t go to museums or art galleries,” she says, “but I had this one aunt who could draw, and that always seemed like magic.” It wasn’t until she was taking classes in a community college that she realized she wanted to pursue an art career and wound up enrolling in a tiny institution called the duCret School of Art in Plainfield, NJ, for a course of study that still promises to provide students with a “solid, realist-based foundation.” There were 20-some others in her graduating class—”and that was in its heyday,” she adds—and the focus was on traditional approaches to drawing and painting. There were no courses in theory, no tutorials in how to build an art career.

Larko moved to Jersey City in 1983, which “wasn’t hip back then,” she notes. She supported herself working the night shift as a computer graphics artist at Murdoch Magazines and later Financial News Network. The evening shifts left her free to paint on location, and Jersey City offered up a bonanza of subjects. For the next two decades, she gravitated to what some might consider the eyesores of the industrial landscape—transformers, synthetic gas plants, and tanks of all shapes and sizes. For five years, between about 1999 and 2004, she also painted in an active salvage yard in Hackettstown, NJ, immortalizing the heaps of discarded appliances, car parts, and electronics that make up the sorry cast-offs of our consumer culture.

When the cable-TV gig dried up, the artist went on unemployment for a couple of years and then worked as both a teacher at the Visual Arts Center of New Jersey and the gallery director at the Tomasulo Gallery at Union County College. She also took charge of her career, holding open studios, networking, and cultivating a base of collectors. “I figured out how to sell artwork on my own,” she says. “I had business cards made up and developed a mailing list. I became the queen of the nonprofits and had my first solo museum show when I was 36, at the New Jersey State Museum.”

In 2002, Larko met her husband, Peter Riccio, a geologist who specializes in extracting special metals and who was then living in Greenwich, CT. The two settled in New Rochelle, and the artist soon found a rich trove of subject matter just a few minutes from home, desolate streetscapes and abandoned complexes whose signage speaks to a more optimistic time, like the Bronx Golf Center, a once vibrant family entertainment center that years ago included a driving range and a miniature golf course.

Other sites, like an observation tower at Orchard Beach, offered a glimpse into the city’s past, becoming like the artifacts an archeologist might uncover. The ungainly three-story structure, as Larko eventually discovered, was built for the rowing team during the 1964 Olympics; its platforms were used by the coaches who could observe the rowers in a nearby lagoon. Though it was fenced off when the artist found it, to deter graffiti artists and kids who might be tempted to play there, she drove by one day and noticed a gate had been left unlocked. She did a quick sketch and then bought a pre-stretched canvas and hastened to the site. But after a week or so, park rangers told her to move on. Through a series of past connections with park personnel, Larko tracked down the Pelham Bay parks administrator, Marianne Anderson, who granted her access for the time she needed to finish the painting. There is something ennobling about Larko’s view of the ungainly tower, and it now seems a fitting testament to its better days, when the U.S. Olympics rowing team won two gold, one silver, and one bronze medal.

Given her subject matter, the artist is often asked if Rackstraw Downes, the British-born plein-air poet of the industrial landscape, was ever an inspiration. But Larko began painting her sites long before she knew about Downes, who is two decades her senior and spends half the year in Texas. The two met in 1994, when a collector alerted her that Downes was painting at a site that depicted his condo building in the background. “We talked about painting in New Jersey,” she recalls. “I told him about my subjects and said if he wanted me to show him some of my favorite industrial sites, I’d be happy to do so.” They stayed in touch, and exchanged studio visits, and in 1996, Downes came to her first museum show at the New Jersey State Museum in Trenton.

Yet Downes was neither an influence nor, as one might hope, a valuable connection to the New York art world. It was not until 2011, after years of promoting her own work and cultivating a base of collectors, that Larko successfully signed on with J. Cacciola, who had recently opened a gallery in Chelsea, and later Michael Lyons of Lyons Wier Gallery, also in Chelsea. “I didn’t go to every gallery under the sun. I would go to galleries that show representational art,” she says. “You really need to do your due diligence as an artist.”

The last few years have brought expanded interest in her paintings, with a 10-year survey called “Bronx Focus” at the Bronx Museum of Art and another solo show, “Hidden City,” at the Susquehanna Art Museum in Harrisburg, PA. Until the Covid19 restrictions paralyzed so much of the art world, she was scheduled to have a solo at Lyons Weir, “Sign of the Times,” which takes its name from the numerous billboards she has painted since the financial crisis of 2008. The title also refers, the press release notes, to the “strange era of planetary and political upheaval” we are living through now.

It’s doubtful, though, that even a pandemic will restrict Larko’s quest for subjects. “Painting on location and experiencing the world around me, with all its messy contradictions and challenges, continues to keep me excited to get back out there and paint.”

Top: Painting on site at the abandoned Bronx Golf Center, 2016

Hello,

How does someone purchase one of Valeri’s paintings? I’ve been a big fan of her work for some time but have not had a chance to see her work in person.

Thank you,

Bill Kirby

Hi Bill,

Thank you so much for your kind words about my paintings and for your interest in giving one a good home. You can contact Lyons Weir Gallery at gallery@lyonswiergallery.com or by phone: (212) 242-6220. They are working remotely while the gallery is temporarily closed.

If you have any questions for me, feel free to contact me at valart87@yahoo.com

All the Best, Valeri

I love your work!! I am definitely contacting the gallery. Despite this difficult time, I feel an obligation to support our visual artists, musicians, and dancers.

Thank you so much Debi!

The gallery would love to hear from you. If you have any questions that I can answer, feel free to email me at valart87@yahoo.com

All the Best, Valeri