A new novel recalls a famous heist.

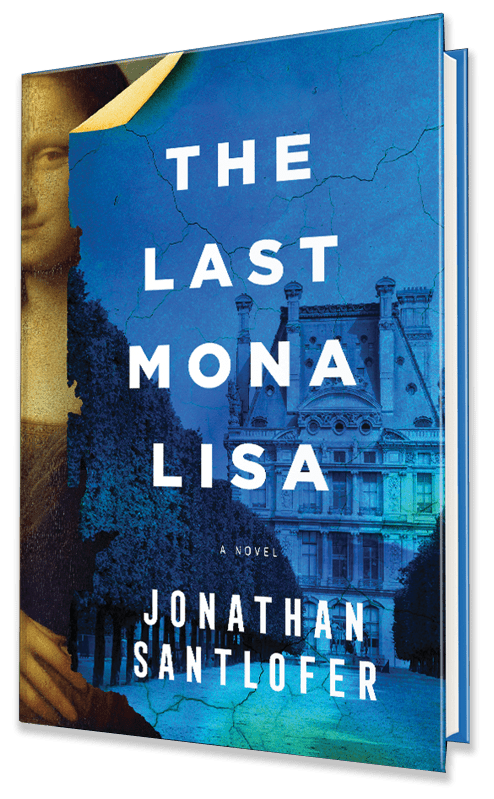

I’ve just finished reading Jonathan Santlofer’s hugely entertaining thriller The Last Mona Lisa, a lively yarn that taps into our present-day fascination with all things Leonardo and takes the reader into the sometimes violent underworld of art theft. The dark mystery at its heart raises the provocative question: Could the Mona Lisa in the Louvre possibly be a fake?

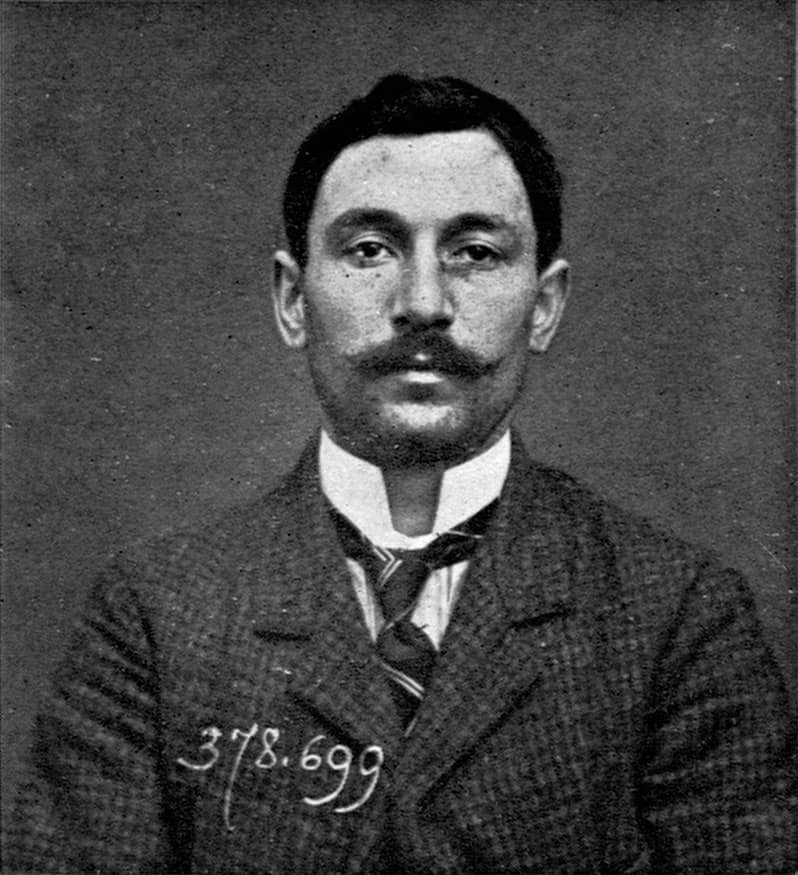

Santlofer’s fictional hero, Luke Perrone, an artist and amateur art historian, is the great-grandson of a real-life thief, Vincenzo Peruggia, who had helped construct the painting’s glass case and did indeed make off with the notorious lady hidden under his workman’s smock. In the course of reading his ancestor’s journal, Perrone sets off on a chase that brings him into close encounters with shifty collectors, an ambitious INTERPOL agent, and a beautiful blonde with a hidden agenda. The story slips back and forth in time, laced with generous doses of art-history and a sprightly cast of shady characters.

After finishing the book, I became curious as to what was real and what was fiction and took to the Internet to sort out what I could. The online excavation unearthed lots of interesting factoids, beginning the with identity of the sitter herself. Mona Lisa was by no means a woman of great interest in her day, nor did her portrait begin to attract all that much attention until early in the 20th century. She was the third wife of a prosperous silk merchant, Francesco del Giocondo. (The work is occasionally referred to as La Gioconda, meaning “the happy one,” but also a pun on her married name). She bore him five children, and the union was, according to all available accounts, a successful one. Lisa’s marriage may have increased her social status because her husband’s family was more prosperous than her own. (She is known as “Mona,” a common contraction of “Madonna,” meaning “my lady,” or “madam.”) In his will, Francesco returned her dowry to her and provided for her future, writing “Given the affection and love of the testator towards Mona Lisa, his beloved wife; in consideration of the fact that Lisa has always acted with a novel spirit and as a faithful wife….”

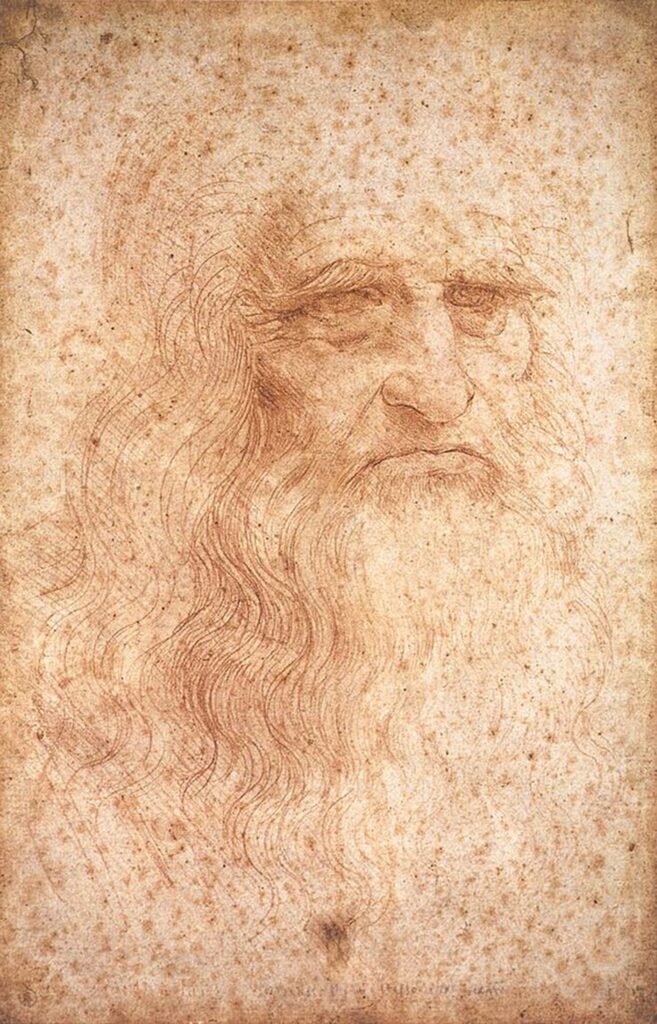

Leonardo was commissioned to paint her likeness in 1503 but most likely had to delay work when he received a tidy sum to begin work on the long-lost heroic history painting The Battle of Anghiari. In 1506, he considered the portrait unfinished and never delivered it to his client. Online accounts claim he traveled with it throughout his life, perhaps completing the portrait many years later in France (somewhere in the dusty regions of my memory, I seem to recall that he strapped the canvas to a mule—presumably safely wrapped—when he made his final journey to Clos Lucé in France, where he spent his last three years as the guest of François I). The eminent art historian Carmen Bambach concluded that Leonardo probably continued refining the work until 1516 or 1517. “Leonardo’s right hand was paralytic circa 1517, which may indicate why he left the Mona Lisa unfinished,” says Wikipedia).

The painting went to the Louvre after the French Revolution, but spent a brief period in Napoleon’s bedroom at the Tuileries Palace. Curiously, few outside a narrow circle of the French intelligentsia paid it much attention until Peruggia, disguised as a workman, prised it loose from the walls of the museum, hid in a broom closet, and walked out with the portrait wrapped in his smock after the museum had closed.

And then the story gets really weird.

A painter visiting the Louvre noticed it missing the next day; the museum closed for a week of investigation and detectives closely searched the museum (the picture’s empty frame was found on a staircase); the ports and eastern borders of France were closed until all departing traffic could be inspected. Lacking very little real evidence, the police set their sights on Guillaume Apollinaire, described in Roger Shattuck’s The Banquet Years as “an art critic, a witty chroniqueur…, a successful story writer, and a man of unconventional brilliance and mysteriously attractive personality.” An acquaintance of Apollinaire named Géry Pieret, who had worked briefly as his secretary, had stolen small statuettes from the Louvre “out of pure bravado.” He sold some to another bright light of the Parisian avant-garde, Pablo Picasso, and left others with Apollinaire. After the theft of the Mona Lisa made headlines all over the world, Pieret “proceeded to sell one of the stolen statuettes to the Paris-Journal, which used it for publicity purposes to taunt Louvre officials about the laxness of precautions against theft,” Shattuck reported. Apollinaire and Picasso, worried about deportation, turned “all the goods over to the Paris-Journal for anonymous restitution.” In the course of their investigations, the police uncovered Apollinaire’s name, searched his apartment, and arrested him a few weeks after the theft of the painting. Convinced they had the real thief, the sûreté put him in solitary confinement for nine miserable days. To compound the humiliation, his cher ami Pablo, “under questioning, denied having any part in the affair and finally even denied knowing his friend.”

So where was the painting during all this hubbub?

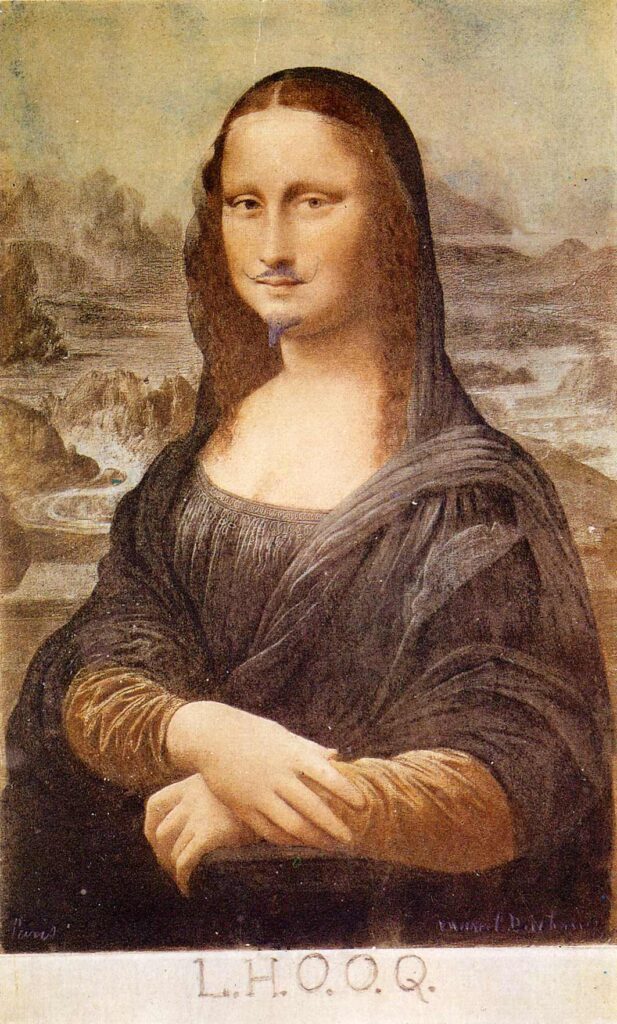

Peruggia kept it hidden in his apartment in Paris for two years and then returned to his hometown of Florence, where he eventually approached an art dealer, who contacted the director of the Uffizi for authentication. Peruggia apparently hoped for a reward for returning the painting to Italy, not realizing that the portrait’s history had landed it legitimately in France and eventually in the collection of the Louvre. He expected a reward but instead ended up under arrest. After its recovery, the painting was exhibited all over Italy with banner headlines celebrating its return. The Mona Lisa was then handed over to the Louvre in 1913. The notoriety it received in the press helped the artwork become one of the best known in the world, ensuring a reputation that has made it the most famous Renaissance painting of all time (though not, of course, in the eyes of many art historians). Mona Lisa’s iconic status has made her the the brunt of several parodies, such as Duchamp’s cheeky LHOOQ (which pronounced phonetically sounds like “elle a chaud au cul” and translates roughly as “she’s got a hot pussy”).

But there are further strange twists to the tale.

In 1932, The Saturday Evening Post, in its heyday one of the most popular magazines in America, gave a whole different account of the affair by journalist Karl Decker. “According to Decker, an Argentinian con man calling himself Eduardo, Marqués de Valfierno, had told him that it was he who had masterminded Peruggia’s theft of the Mona Lisa,” wrote Ian Tattersall and Peter Névraumont in their 2018 book Hoax: A History of Deception. “And that he had sold the painting six times!”

“Valfierno’s plan had been a pretty elaborate one, and it had involved employing the services of a skilled forger who could exactly replicate any stolen painting—in the Mona Lisa’s case, right down to the many layers of surface glaze its creator had used. By Decker’s account,” according to Hoax. “Valfierno not only sold such fakes on multiple occasions, but used them to increase the confidence of potential buyers, ahead of the heist, that they would be getting the real thing after the theft…. Those copies had been smuggled into America prior to the heist at the Louvre, when nobody was on the lookout for them, and the well-publicized theft itself served to validate their apparent authenticity when they were delivered to the marks in return for hefty sums in cash.”

The problem is that no one has ever been able to track down Valfierno or verify any parts of Decker’s story in The Saturday Evening Post (where were the fact checkers? one asks.) So, in all likelihood, the Mona Lisa in the Louvre is the real deal. She is now serenely and securely behind glass, visited by something like a pre-pandemic estimate of 30,000 visitors a day, who are allowed barely a minute to snap a selfie with the enigmatically smiling icon of Renaissance womanhood.

Out of these tantalizing strands of facts and fiction, Santlofer has woven a rousing tale. Check it out, enjoy the read, and the next time you’re in the Louvre, go visit Titian’s Man with a Glove. A far sexier portrait, in this writer’s opinion.