When Susan English was three or four years old, she lived in Belgium with her family for a couple of years. Years later she still remembers a babysitter named Hele placing a candle inside a child’s play igloo. “It made a big impression on me,” English says. “The light inside the snow was absolutely magical and the space seemed to dissolve. I had a visceral reaction to the translucent effect and the dissolution of borders.”

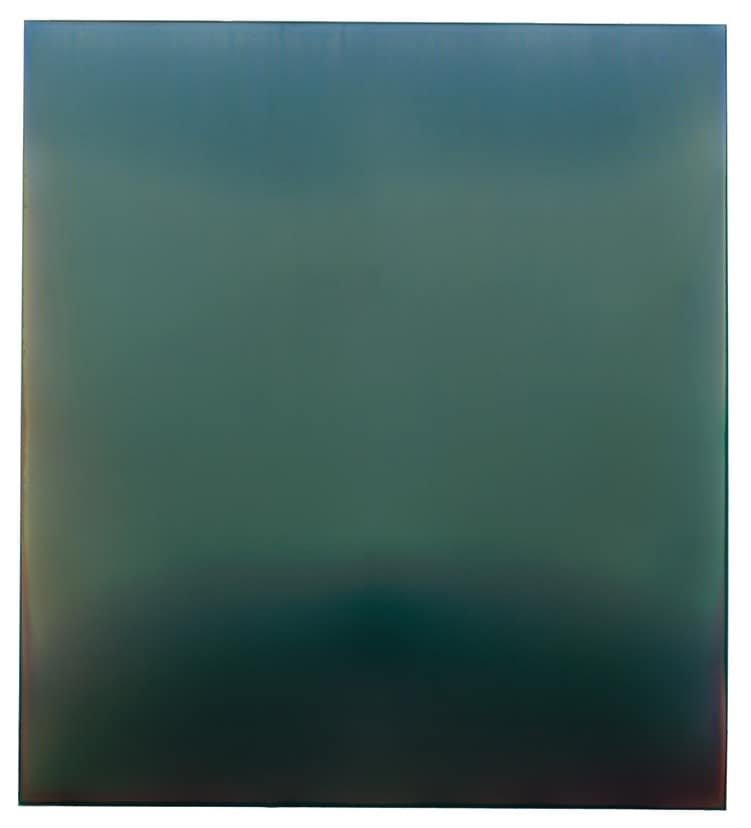

Looking at the artist’s work now, which you can see at Kathryn Markel Fine Arts in New York’s Chelsea neighborhood through May 4, it’s almost uncanny how the qualities that enthralled her when she was barely more than a toddler have resurfaced in her paintings of the last few years. Made of many layers of poured polymer, the works’ “surfaces range from dull to glossy, either absorbing or reflecting the light, existing always in relationship to the light in the room or the position of the viewer,” as she puts it on her website.

By the time she was in high school, growing up in Bethesda, MD, just outside Washington, DC, English knew she wanted to be an artist and was making trips to museums in the nation’s capital. In her senior year, she was particularly impressed by Barnett Newman’s “Stations of the Cross” at the new East Wing of the National Gallery. “There was a painting on every wall in a circular room, and I was there all by myself,” she recalls. “At that point I wasn’t making abstract work, and it would take me a long time to get to abstraction, but it spoke to me strongly.”

At Hamilton College, English ended up a ceramics major and says “there’s a sculptural aspect of my work that probably started there. I made abstract ceramic sculptures based on organic forms. They were tiny and sat on a table top. But I never liked the loss of control that happens when you fire ceramics.”

After graduation, she spent a year and a half on Nantucket, setting up a studio in a rental house and devoting herself to painting, making works that were, as she describes it, “a cross between Bonnard and Hopper,” but with no figures and “constructed in a very abstract way.” Though she was picked up by a local gallery and could make a living as a house painter, she was soon off to New York, where she enrolled at the New York Studio School. Her teachers in the rigorous two-year program included the esteemed second-generation Abstract Expressionist Esteban Vicente and Robert Storr, future curator at the Museum of Modern Art. In particular, she was impressed by Storr’s level of seriousness. His course included four hours of drawing in the morning and four hours of painting in the afternoon, five days a week. “He was about understanding painting in a very deep way. He looked at everything, and he talked about everything.”

To support herself, English worked as a decorative painter, doing faux finishes and wall glazes and advising well-heeled clients on what colors would work best in their homes. “It was fairly lucrative and gave me a lot of flexibility and free time to be an artist.” The job also helped her understand “how colors function in a relational way,” an interaction that describes most of her mature work.

When she entered Hunter College to pursue an MFA in 1987, the artist stepped into a minefield of opposing opinion in different academic camps. Art historian Rosalind Krauss, whom she describes as a “spellbinding lecturer,” offered up her own powerful interpretations of modern art. “Krauss used deconstructionist, post-structuralist and feminist theory to re-orient our perspective on the history of Modernism.” In another camp, Maurice Berger, then a budding cultural critic with strong interests in identity and self-representation, was “totally anti-painting.” The members of the fine arts faculty, who brought up the arrière-garde, were all color field painters. She describes the atmosphere as “pretty hostile,” but says the in-fighting only reinforced her dedication to painting. While still at Hunter, she met her husband, John Harms, also a painter, and gave birth to her first son, an accidentally rather revolutionary move. “Nobody brought a baby to classes in those days.”

The young family moved to Prospect Park in Brooklyn, and English and Harms teamed up in the decorative painting business to support themselves. “We had a loft space on Fifth Avenue, before gentrification, and it was pretty rugged,” she recalls. By the time she got her MFA, English describes her efforts as “fairly mature. I was making large works that had a singular alignment, curving lines inside them, hourglass shapes. The most obvious relationship was with Robert Mangold, but the quality of the line I was making was very sculptural.”

When her second son was born five years later, the couple made the decision to move out of the city up to Cold Spring, NY, close to where Dia: Beacon, the ambitious cavernous museum for contemporary art, would soon be established in 2003. “It was this incredible thing that totally transformed the town,” English says. “I was working as a teaching artist at Dia and got to know the collective extremely well. I had been aware of the Light and Space artists, and I soon became much more aware of them.” And of Agnes Martin, who was then near the end of her life and had a gallery devoted to her large, austere grid paintings. When she visited in a wheelchair with then-director Michael Govan, Martin told a group that included English: “Be true to yourself.”

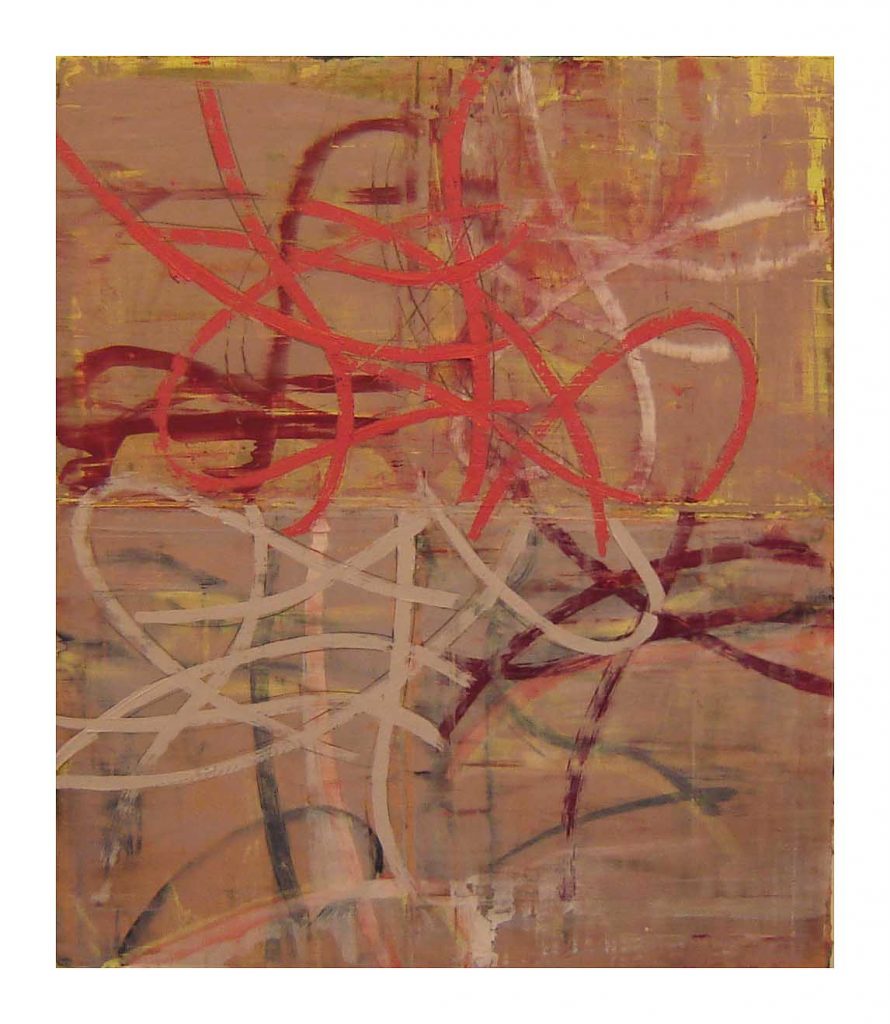

The artist also became involved in a nonprofit called Collaborative Process, which offered a space where she started showing her work and curating exhibitions. After her sons went off to college, she says, “I worked harder on the career aspects of my work” and for a while showed with Jacquie Littlejohn Gallery in New York. In spite of suffering a bout with breast cancer, English moved into ever more adventurous territory, including a series called “After Guatemala,” whose tangled loops may recall Brice Marden’s “Cold Mountain” paintings from 1989-91.

The artist began making what she calls “tiny sculptural things,” and those led to poured shapes, some of which looked like attenuated musical notations. “I had little blocks of wood with a geometric aspect to them. With those, I realized I wanted to figure out a way to build up the surface of the work and turned to pouring polymer,” English says.

“I started with rectangles, 11.5 by 11 inches just off a square, and poured the paint on to wood panels,” she continues. “I cut them up into four, and started getting a sequence, both on the horizontal and the vertical. Then when I scaled up, they became much more minimal.”

The upshot, in just the last few years, has been a seductive fusion of spare geometries with dense but lyrical floods of color. Notes critic Stephen Westfall in the catalogue for her show at Markel, with which she has been affiliated since April 2017: “the effect is that of luminous, windless, hovering veils imbued with daylight.”

And the possibilities for the future abound with promise. “I don’t feel like I’m anywhere near bored with exploring what there is to explore,” she says.

Ann Landi

Top: An installation shot of English’s show, “Periphery,” at Kathryn Markel Fine Arts, New York, NY, though May 4, 2019

This is a really interesting piece about this artist’s evolution and her work is stunning!