No doubt there are those who are familiar with the paintings of Maria Lassnig, the Austrian-born artist who kicked off Kate Petley’s round of fantasy curating on the site two weeks ago. But I had never heard of her before and was beguiled by Lassnig’s You or Me (2005), which Petley summed up as “one of the most psychologically charged self-portraits” of our times. We the viewers are both victim and voyeur as the artist points a gun at us and another at her own head. The anatomy of a naked older woman is realized in luscious, almost treacly flesh tones, but the face and figure appear to quiver in fear and panic.

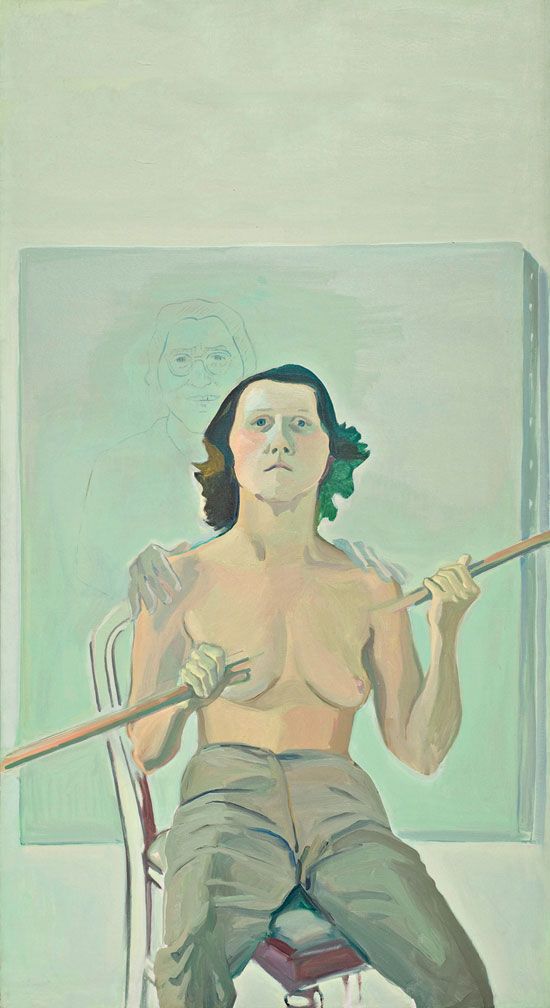

Self-Portrait with a Stick (1971); the shadowy outline of Lassnig’s mother can be seen in the background

Intrigued, I went looking for Lassnig online last week and discovered that she’d been amply exhibited and fêted in the last in the last 20 or so years of her life (she died in 2014, at 94), both here and abroad, with shows at the Centre Pompidou, the Serpentine Gallery, and a generous overview at MoMA’s PS1. Her brand of high-keyed expressionism now looks fresh and timely and has influenced younger and critically lauded painters like Nicole Eisenman, Dana Schutz, and Amy Sillman.

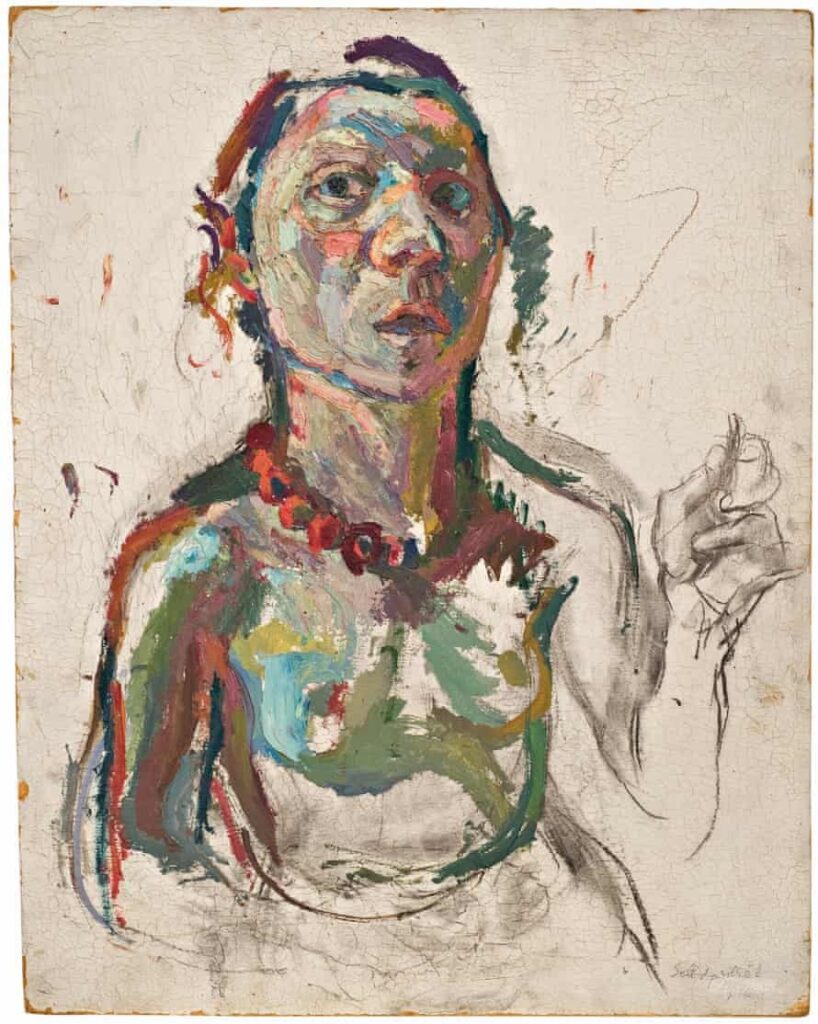

Lassnig was born out of wedlock in 1919 in a tiny town in the Austrian state of Carinthia Her mother later married her father, a much older man, but the relationship was troubled and tempestuous and Lassnig was raised mostly by her grandmother. She taught school until the age of 22, when she decided she’d rather be an artist. “So she biked all the way to Vienna to attend the Academy of Fine Arts,” according to one account. It was the height of the war, the Nazis were still in power, and the approved style was the kind of drab socialist realism that Gerhard Richter also absorbed during his student years. By 1945, though, her style of self-portraiture—questing, primitive, even slightly comic—had taken root, influenced by Austrian masters like Emil Nolde and Oscar Kokoschka. Three years later she coined the term “body consciousness” (Körpergefühlmalerei in her native German) to describe her practice. “Lassnig depicted pain, thought, blood and breath, as if they were objects she could hold and scrutinize,” claimed Kathryn Hughes, a critic for the Guardian. “The truth,” the artist once explained, “resides in the emotions produced within the physical shell.”

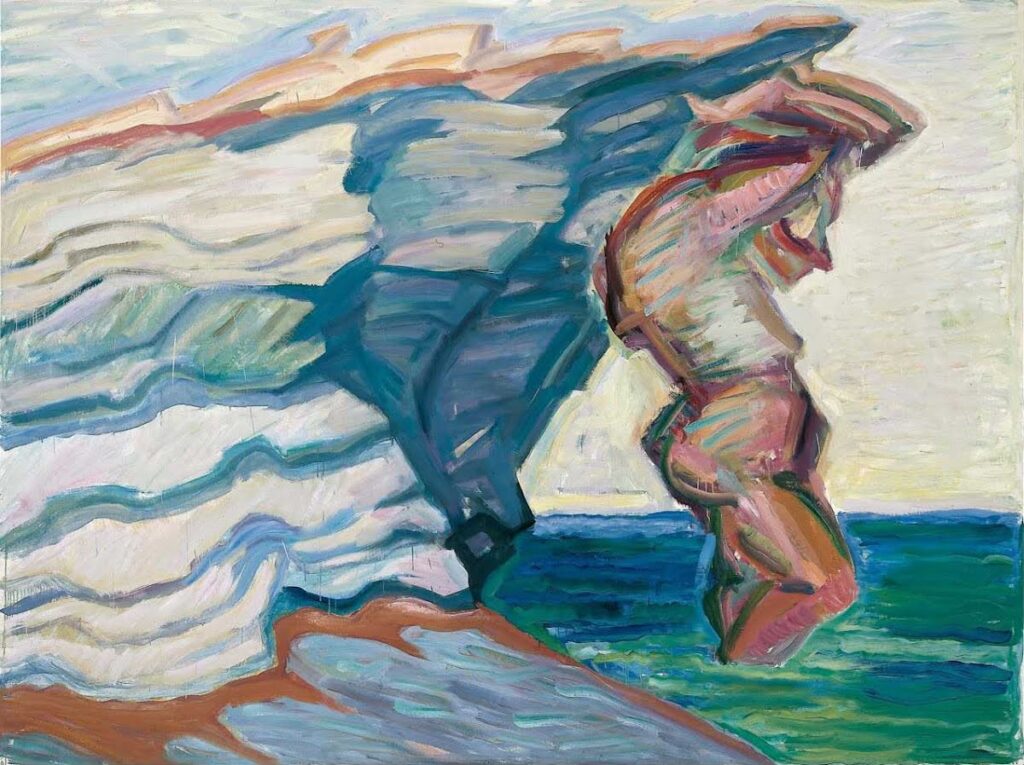

In 1951, she left Austria and studied in Paris on a scholarship. There she met artists and poets like André Breton and Benjamin Peret. This was of course long past the heyday of Surrealism, and though critics have seen their influence in her abstract compositions from these years, Lassnig never considered herself a Surrealist. She was not painting hokey dreams or fantasies, but rather the real-life sensations of her own body.

“She restricted herself to depicting only those parts of herself that she could physically feel: if the back of her head went numb she left it out, if her ears seemed unreachable they went missing, and she rarely painted her hair on the grounds that it was already dead,” wrote Hughes. “The result was a body on the canvas that often looks partial, even deformed. In a Lassnig painting limbs are regularly abbreviated into vestigial knobs, a torso is detached, an ear ends up on a dinner plate.”

In 1968, at the age of 49 Lassnig moved to New York, where she studied animation at the School of Visual Arts and forged friendships with, among others, Louise Bourgeois, Joan Semmel, and Carolee Schneemann. A review in Hyperallergic in 2014 refers to the “generative environment…in which Maria Lassnig thrived — where she could explore and experiment. Her friends describe the artist as a modest, ladylike, even self-effacing woman, who would rather talk about the work of others than her own. But her art was fiercely feminist, so there were contradictions and struggles within her, which fight it out in the paintings and animated films.”

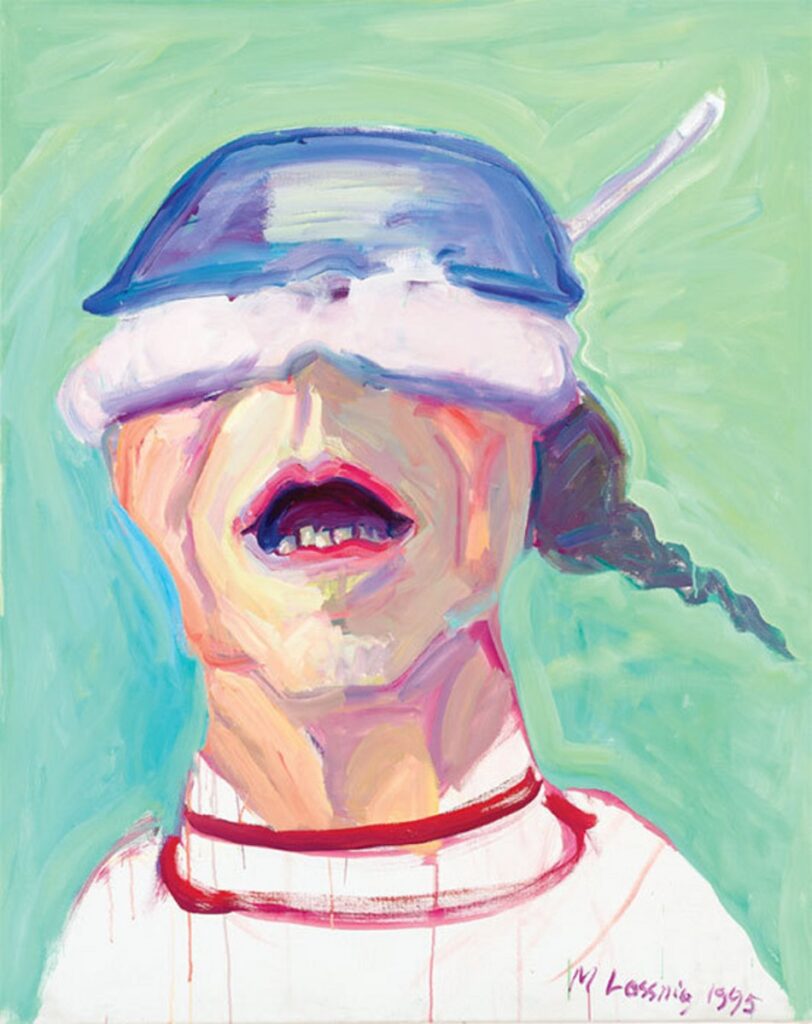

Her brand of fierce but often clownish feminism made itself felt in a series of “Kitchen War” paintings from the 1970s through the ‘90s, which critiqued women’s relationship with domesticity. “In The Kitchen Bride (1988), the artist transforms herself into a giant cheese grater and makes a bow of obeisance to the household gods,” wrote Hughes. “Meanwhile in Self-portrait with Saucepan (1995), she wears a cooking pot on her head.” Her obituary in the New York Times quotes her attitude toward traditional female roles: “When I was young, I was clever enough to know that if I got married or had children, I would be eaten. I would be sick if I couldn’t paint, and I would be schizophrenic because I would have wanted to [both paint and raise a family]. So I renounced it.”

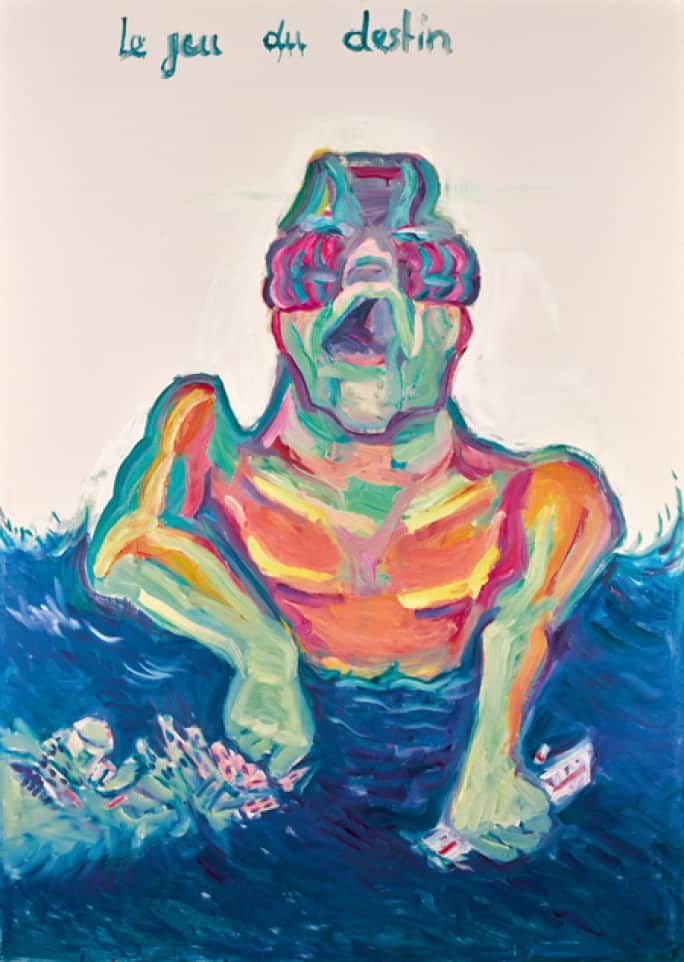

“She had fun representing herself in outrageous roles: as an astronaut, an extraterrestrial, a robot, a monster, a baby,” recalled fellow filmmaker Silvia Goldsmith in Hyperallergic. “And there is a searing social/political consciousness coursing through her loosely painted, acidly colored art — the tanks and missiles zooming across her 1980s canvases; the animals she depicted with soulful empathy; and above all, the confrontational self.”

During her time in New York, the Austrian government declared her Artist Laureate. There was a “hilarious ceremony at her loft, which was almost bare: 1 cup, 1 saucer, a plate, a bowl, a bed, a few chairs and a table,” recalls another friend, Martha Edelheit, a pioneering feminist artist who now lives in Stockholm. “We stood in the middle of the loft in a circle and these very uncomfortable Austrian gentlemen in their business suits crowned her with a laurel wreath and opened a bottle of champagne, with plastic glasses. The art school in Vienna, the University of Applied Arts, offered her a professorship. She didn’t want to go back, she liked living in New York. She said that if they paid her what they paid Joseph Beuys, she’d return! They did…and she felt she had to go back.”

Lassnig remained in Europe for the rest of her life, gradually accruing numerous honors, participating in a bevy of shows, and enjoying a more prestigious reputation than she might have realized in New York. While oil was her primary medium, in the 1980s she frequently used watercolors in her paintings. Her works from the 1990s and 2000s featured semi-figurative, semi-abstract representations, mostly of herself that were often in a cooler palette, and fleshy and naked, as if bodies were turned inside out.

Since 2014, her work has been shown at the Fondacio Tapies in Barcelona (2015), Tate Liverpool (2016), and the Albertina, Vienna (2017), the National Gallery in Prague (2018), Kunstmuseum Basel (2018), and Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam (2019). Like Alice Neel, another painter whose ferocity and freshness resembles hers, Lassnig seems destined to go down as one of the great originals of our times.

Top: Self-Portrait with Lobster, 1979

I saw Maria Lassnig’s work for the first time in a museum in Austria and was intrigued since I work figuratively. She’s an original. There was also an exhibit we saw where contemporary artists were paired with older masters. She had a nude self-portrait next to a nude by Rubens. Very striking. I took a photo and could find it and send it if you’re interested.