I first encountered a couple of John Outterbridge’s trippy, sexy, irresistible sculptures on a press trip to Los Angeles in 2011 for the first iteration of Pacific Standard Time, the sprawling series of exhibitions devoted to art in southern California. It was love at first sight. When I learned that he died in November, I was sorry I’d never taken the time to get to know his work more thoroughly, and that I’d never lobbied to write a profile of the artist when I was working for ARTnews.

Born in Greenville, NC, in 1938, Outterbridge was the second of eight children and liked to say that his parents were the first artists he ever knew. His father hauled and scavenged junk for a living, and the backyard was heaped with cast-off flotsam and jetsam. “The family home was covered with paintings by the children — even some window shades were hand-painted,” The New York Times obituary reports. “And he was surrounded by the beauty of homemade things: his grandmother’s soap bars, stacked like buildings; wood floors bleached bone-white by all the lye; tall poles outside decorated with gourds that rattled and scared away the birds.”

After serving in the Army (where one of the officers created a studio space for him), Outterbridge attended the American Academy of Art in Chicago and, after marrying in 1963, moved to Los Angeles. He worked in a production studio, taught art classes, and became an art handler and instructor at the Pasadena Art Museum, where he met leading lights of the avant-garde like Robert Rauschenberg, Richard Serra, and Mark di Suvero. His first major body of work, known as the “Containment” series, was created in the wake of the Watts riots in 1965 and immediately read as a reaction to racial oppression. For these, “he covered wooden armatures with pieces of sheet metal to create the illusion of bulk and weight, sometimes incorporating straps, buckles or ties that evoke notions of physical restraint or slavery,” notes the Times.

Rags became a dominant motif in his work for the series he pursued for the next 40 years. In one called “Ethnic Heritage,” for instance, he fashioned dolls from metal, wood, red clay, rags, human hair and more. Watching his young daughter at play offered the initial inspiration, but the inclusion of materials like shells and beads recalls traditions in African art. For a show called “The Rag Factory” in 2011 in Los Angeles, Outterbridge made a site-specific installation that consisted of brightly colored rags tied together into long strands that extended nearly floor to ceiling like columns.

For almost two decades, beginning in 1975, Outterbridge was the director of the Watts Towers Arts Center, an education and exhibition space inspired by the collection of 17 interconnected sculptural towers and other structures folk-art hero Simon Rodia built by hand and decorated with found glass, pottery shards and more. It was a fitting occupation for an artist consumed with making statements from the culture’s discards.

Throughout his long life, he continued to comb the junkyards in Pasadena, near his home in Altadena. Like Robert Rauschenberg, he operated in a kind of gap between art and life. “Art and the creative process always belonged to humanity at large,” he told an interviewer for Art in America. “No matter what their complexion, no matter what their posture, people always expressed themselves in some way. That expression, to me, has always been about some form of art. So I grew up not knowing I was doing anything but participating in life. I didn’t see art as a separate thing.”

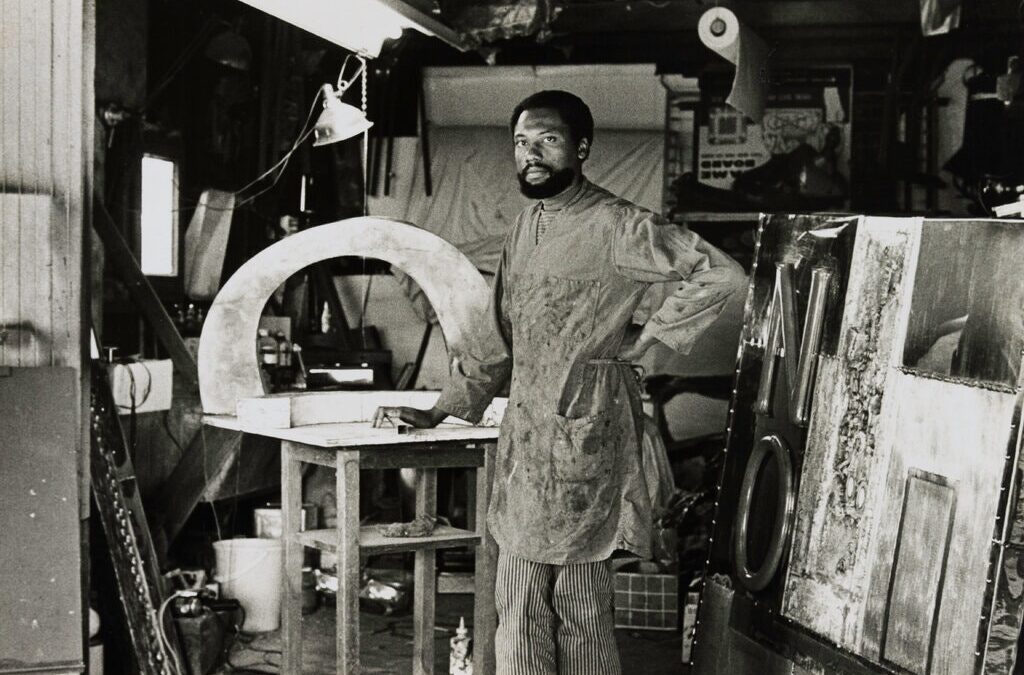

Top: John Outterbridge in his studio in Altadena, CA, 1970. Photo by Robert A. Nakamura for The New York Times