A Major Abstract Artist of the 20th Century Begins To Get Her Due

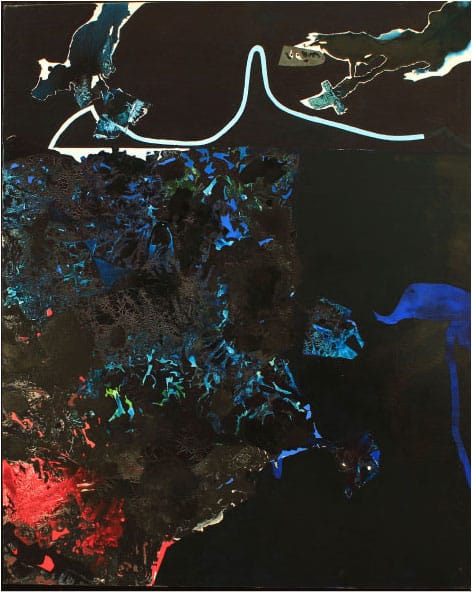

I first stumbled upon the paintings of Dorothy Hood about five years ago, in the home of collector and artist Dora Dillistone. It’s not too much of a stretch to say that I was completely blown away. These are large, emphatically lyrical works, with broad swaths of limpid color broken up by jagged lines and collage-like shapes and patches. They reminded me a little of aerial views of the planet’s surface, and also of the canvases from the 1950s and ‘60s of Helen Frankenthaler and other Color Field painters.

“Who,” I asked Dora, “painted those?”

“Oh, that’s Dorothy Hood,” said Dora, who spent many years in Houston. “She’s from Texas too.”

And that was my introduction to the works of this remarkable artist who, like so many, fell between the cracks of art history, this time with not one but two strikes against her: she was female, and she matured far from the mainstream buzz and star-making opportunities of the New York art world in the heyday of AbEx and Greenbergian formalism.

But now if you’re lucky enough to get to the Art Museum of South Texas in Corpus Christi for “The Color of Being/El Color del Ser: Dorothy Hood (1918-2000),” between September 30 and January 8, 2017, you can check out 160 of her works gathered from museum and private collections around the world.

Hood’s early childhood in no way presaged the sort of tumult and ambition that lay ahead. She was raised in Houston, the only child of a prosperous banker and his fragile wife, but her parents separated when she was eleven and her health deteriorated as she suffered from anemia and pneumonia. By the time she was in her teens, however, both her ripe blonde beauty and her talents as an artist were obvious. Through the efforts of a supportive high-school art teacher, she won a four-year scholarship to the Rhode Island School of Design.

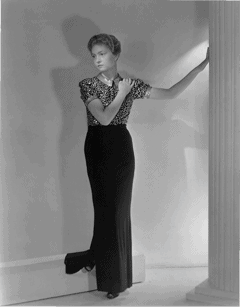

After graduating from RISD, where her forte seems to have been making miniature ceramic figures, she headed for New York, working as a fashion model to support herself and pay for classes at the Art Students League. In 1941, on a whim, Hood and two friends drove to Mexico City. And what she found there changed her life. “The Mexican Revolution was only twenty years over—its fires and illusions and memories were still alive in the air. It was an era of action for artists and intellectuals,” she recalled.

What was supposed to be a two-week vacation turned into a 22-year love affair with the country and its artists. “In the early 1940s Mexico was as culturally adventurous as any place on earth, with experimental artists taking the bare bones of European modernism and shaping distinctive new anatomies from it,” notes the show’s curator, Susie Kalil, in her catalogue essay about the artist.

Hood became friendly with Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, the surrealist painters Leonora Carrington and Remedios Vara, poet Pablo Neruda, and especially with José Clemente Orozco, the great Mexican muralist whose intense depictions of war and revolution helped inform her own early and haunted visions of waiflike children, women huddled in dark corners, and stampeding horses. By the time she was 25, a resident of the city for only two years, she had her first solo show at a prestigious Mexico City gallery.

Hood left Mexico briefly in the middle of the decade, spending time in Houston and New York, where she developed important relationships with the influential Museum of Modern Art curator Dorothy Miller and the director of the esteemed Willard Gallery, Marian Willard. She was “exposed to the front lines and demands of the art world, and she understood it,” writes Kalil of the artist’s encounter with the seductive Chilean painter Roberto Matta. “With her striking beauty she could have lived as a muse in that world, but she was not content to do that.”

After little more than a year on the East Coast, however, she returned to Houston and “worked in the shipyards as part of the war effort, earning four hundred dollars for travel and expenses back to Mexico,” according to Kalil. There she met and fell in love with José Maria Velasco Maidana, a handsome and charismatic composer and musician 22 years her senior. “When he walked through the streets of Mexico, some say, children would follow him and give him flowers,” noted the writer Katy Vine in Texas Monthly. “Harlequin bodice-ripper authors could not have invented a more romantic partner.”

They married in 1946 and spent the next few years traveling back and forth between Mexico, Houston, New York, and Central America so that Maidana could pursue his conducting career. Hood’s direction as an artist meanwhile was moving toward ever greater abstraction, and in 1950 she landed a solo show at the Willard Gallery, a rare feat for a woman at that time. Hood’s life throughout the ‘50s was peripatetic, as she and her husband spent time in Puebla, a town southeast of Mexico City, and then in Mt. Vernon, NY, where they became involved in a medallion jewelry business. And then it was back to Mexico for a few years, until she began to worry that she was perceived as an interloper, a foreigner in a culture that she had known and loved for decades.

In 1962 the couple moved to Houston for the long run. “The city’s art scene,” says Kalil, was “intimate and self-supporting in the 1960s. It was formed by a small nucleus of artists who were attracted to the sense of romance, opportunity, isolation, and open space that Houston offered. Hood stepped into this milieu—a turf vigorously dominated by male artists—when she made Houston her permanent home.”

As an older artist, and a woman, Hood felt somewhat isolated from her peers, but respect for her work was immediate. She found avid support from Meredith Long, an important dealer in town, and by the end of the decade, “she had uncovered what she needed to use as an artist, pushing form, structure and color, as well as the imagination…and the sensual to their very edges,” notes Kalil. Thanks to a benefactor and friend who was the director of the Contemporary Arts Museum, she soon had a small building to use as a studio and the size of her paintings began to grow, so that she was working on ten-by-eight-foot canvases that, says one critic, “did not sit quietly on the wall.”

As her work gained in size and sophistication and confidence, her personal life went into a tailspin. Maidana, already afflicted with Parkinson’s disease, was soon suffering from senile dementia. Hood continued to dote on him, even as he required constant attention, but in 1973, “while visiting Europe on a travel grant, she met Baron Krister Kuylenstierna, a tall, dignified man with thick eyebrows and an intense face who counted among his friends Frank Lloyd Wright, Carl Jung, and Aldous Huxley,” writes Vine. “She quickly developed a daily correspondence that continued until his death, in 1987, interspersed with passionate rendezvous around the world.”

The 1970s, when Hood was in her fifties, marked a sea change in her fortunes as an artist. She had solo shows at the contemporary museum in Houston, at Rice University, and the Tibor de Nagy Gallery in New York. She won awards and placed work in important collections. A solo show of drawings traveled the country. “All she needed was a major show at a New York gallery that would transform her from a regional painter into a significant American artist,” writes Vine. “Hood was on the verge of stardom. She could feel it.”

But the New York art world seemed closed to her, even if by then there were more women on the scene. As an example, Kalil found a letter to Hood from a gallery that represented Joan Mitchell at the time, which said, in essence, “We like your work but we already show Joan Mitchell, and she wouldn’t want another woman in the gallery.”

After both Maidana and Kuylenstierna died in the 1980s, Hood seemed to lose her bearings and some of her earlier bravado. She became involved with a handsome geneticist, Krishna Dronamraju 17 years her junior, with whom she traveled to India, and she began to inject intimations of mortality and spirituality into her work, especially the collages she was making during her later years.

Though he was able to find homes for her work to prestigious collections, Long’s relationship with Hood grew ever more strained, with the artist complaining that he was not putting enough effort into promoting her, and the dealer claiming she was doing too many sales out of her studio. In 1996, they severed ties, and at the age of 77 Hood was without a gallery. A short time later she was diagnosed with breast cancer. She managed to set up a foundation that would care for her legacy, but increasingly Dronamraju controlled access to her and to her work, an off-putting situation for dealers who had an interest in representing her. She died in 2000, leaving Dronamraju as the sole heir to her estate.

Regrettably, because of internal politics and the costs of crating and shipping Hood’s enormous paintings, the show at the Art Museum of South Texas will not travel. But perhaps it will spark renewed interest in this enormously gifted artist, whose works deserve a wider audience in this country and abroad.

Ann Landi

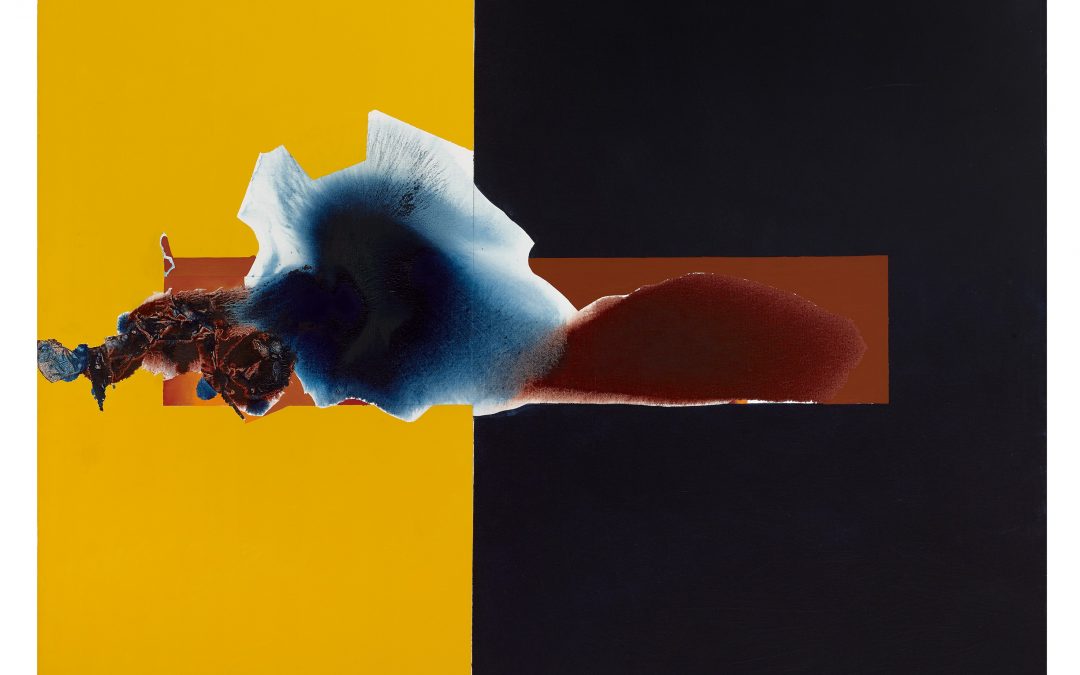

Top image: Untitled (orange and black), oil on canvas, late 1980s, 96 by 120 inches.

Beautiful work, thanks for writing about her, and for beginning to fill out the many gaps in art history. I always feel more alive and filled with hope when I encounter an unknown serious female artist.

I’ll have to travel to Corpus to see this work !

Great article. Thank you so much, Ann. I’m hoping that through Vasari21’s reach that Dorothy will become better known… and that somehow, with enough social media discussion, another museum will take the risk of showing her work, and take this retrospective. She deserves it.

Wow what a saga! Thanks for helping to bring her life and art back into the public eye Ann!

The Art Museum of South Texas (AMST) asks the editorial staff to correct two inaccuracies in the above article:

1. While in Mexico, Dorothy Hood was mentored by the great Mexican muralist Jose Clemente Orozco.

2. The Art Museum of South Texas will tour the exhibition to other museums after the current exhibition concludes on January 8, 2017.

Corrected! Thanks.

Thank you for the information on this wonderful artist.

I studied with Dorothy Hood for a while. She certainly was an outstanding artist, who should be better known. Thank you so much for the article Ann.

Thank you for introducing me to the work of this incredible artist!

My husband bought a drawing from Dorthy Hood for $100 when he was 10-years old. It still hangs in our living room.