A prescient dealer begins to get her due as an artist

Betty Parsons was the sort of art dealer who is invariably dubbed “legendary” when her name appears in the annals of art history. At the Betty Parsons Gallery on West 57th Street, which she opened with a borrowed $5,000 in 1947, she showed the work of the young titans who would change the course of American painting: Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Ad Reinhardt, Barnett Newman, and Clifford Still, among others. Later, she was one of the first to promote the work of female artists, such as Agnes Martin, Hedda Sterne and Anne Ryan (all included in the Museum of Modern Art’s show of women abstract artists through August 13).

Less well known are her achievements as an artist herself, a calling she determined to make her own after seeing the Armory Show of 1913 as a teenager. But now an exhibition at Alexander Gray Associates through the end of this month, “Betty Parsons: Invisible Presence,” offers a chance to assess her accomplishments as a painter and sculptor.

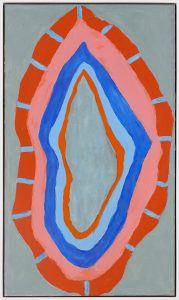

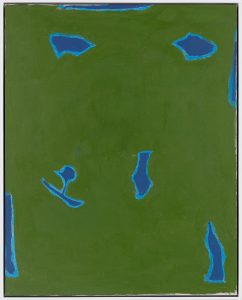

Too often she was dismissed in her own time as a talented hobbyist, “unlikely to eclipse the historical importance of [her] gallery,” as Roberta Smith notes in her review of the show for The New York Times. The 60 works on exhibit range from small bronze sculptures made when she was 22 to sunny watercolors realized on travels to exotic places to small sculptures in wood fabricated toward the end of her life. But the standouts, as Smith notes, are the 14 radiant abstractions that seem a response to the innovations of Color Field painters in the 1960s—big saturated paintings with minimal imagery and a brash assurance. My personal favorites, though, are the small, quirky sculptures like Punch and Judy Theater (1975) and African Village (1981)—offhand, almost childlike assemblages that show her confidence with unassuming materials (it seems no accident that she was the first to represent Richard Tuttle).

Parsons (born Betty Bierne Pierson) was the scion of an old New York family. It was not considered fitting for a woman in her milieu to go to college, so she took classes at the Parsons School of Design, and moved to Paris in her twenties to continue her education. She studied at Antoine Bourdelle’s Académie de la Grande Chaumière, alongside Alberto Giacometti and Isamu Noguchi, and was part of the lively circle of American expats that congregated around Picasso and Gertrude Stein.

In spite of firsthand exposure to some of the most advanced art of her day, Parsons did not turn to full-blown abstraction till around the same time that she opened her gallery, in the late 1940s. When she returned to the U.S. in 1933, she settled in Santa Barbara and Hollywood, CA, for a time teaching art, painting portraits on commission, working in galleries, and studying with Alexander Archipenko. What later drove her into gallery work in New York, according to Abigail Winograd’s excellent catalogue essay for the show at Alexander Gray, were “financial considerations” and it was her career as a dealer that kept her afloat. “We cannot say that Parsons was uncomfortable with the limited attention her work was paid by the critical establishment,” writes Winograd, “but given the fact that she continued to produce and show work as well as her consistent tendency to identify herself as an artist confirms that she was not, nor did she think of herself as, just a Sunday painter.”

Some inkling of a stubborn and determined personality shines through the chronology at the end of the catalogue. She was married to Schuyler Livingston Parsons, an affluent socialite ten years her senior, in 1919. Two years later she moved to Paris, divorced Parsons, and was disinherited by her family (reading between the lines, it seems she had no fear of scandal and was headstrong enough to go her own way at a relatively young age). In 1923 she bought a house in Montparnasse and settled there for the next decade with her lover, fellow artist Adge Baker, and their dog Timmy.

Her relationship with Agnes Martin, as recounted in Nancy Princenthal’s recent biography of the younger artist, gives evidence of just how shrewd, difficult, encouraging, and prescient Parsons could be when it came to recognizing talent and promise. She first met Martin on trips to New Mexico in the summers of 1956 and ’57. Martin at that time was pursuing a kind of woozy biomorphic abstraction that scarcely hinted at the kind of revolutionary painter she would become. Parsons bought five of Martin’s works and promised to show her paintings on the condition that she move to New York. The transition eventually made history, because Coenties Slip in downtown Manhattan, among a coterie of similar innovators like Ellsworth Kelly and Robert Rauschenberg, was where Martin found her true voice.

But Parsons, with whom she may have had a brief romance, was not an easy business partner. “Martin would get quarterly statements from Parsons indicating, ‘after expenses for moving, storage, and publicity, I owed her money….I just couldn’t live on what I was getting from Betty,’” according to Princenthal’s account. But in the end Agnes Martin expressed mostly gratitude: “She came to Taos and bought enough so that I could get to New York and start up. She put me up until I found a place to stay,” Martin recalled.

Betty Parsons was from the outset one tough cookie, alert to the changes in the artistic winds of her day, and well worth the sobriquet “legendary.” That she found the time and energy to make art at all is something of a miracle. Who can say the same about any of the hard-driving male art dealers—Leo Castelli, Sidney Janis, Ivan Karp, or Dick Bellamy—of her generation?

Ann Landi

Top: II Oglala (1979), acrylic on wood, 31″h by 33″w by 16″d

All images courtesy Alexander Gray Associates©Betty Parsons Foundation

I loved this article. It’s so refreshing to read about courageous do what they loved.

And…I’m in total agreement about her sculptures and paintings. Such quirky, humorous color. Yummy!

Great article. Makes me want to know more.

Did not know that Betty Parsons also made her own work. Thanks for posting!

This could be your next documentary, Marcie!

Fantastic article on Betty Parsons – I had no idea! Wish I had known about this exhibit when I was in NY last week.

Really enjoyed this article about Betty and seeing her impressive work. What a wonderful sense of color and form. Thanks Ann!

I so appreciate your writing voice, your choice of words, and your insights and opinions.

I’m enjoying this site so much!

Thanks to my father who told me about this web site,

this website is actually amazing.