Like many little girls, Marietta Patricia Leis first set her sights on becoming a ballerina. “At the age of seven I was entranced with wanting to be a ballet dancer,” she says. As a child in suburban East Orange, NJ, she studied dance every day after school, and though the passion eventually faded, she says she later recognized that those classes were the seeds of a serious discipline that has served her ever since. “The repetitive barre exercises I performed each day for self-improvement gave me a deep understanding of the value of hard work,” she states in her online artist’s bio. And exposure to George Balanchine’s elegant choreography—its clean lines and spare movement—planted an admiration for the minimalist vein that runs throughout her mature work.

But even as a kid, Leis (pronounced like “lease”) found studying ballet an isolated experience, and so in high school she gravitated to acting and performed in summer stock. “As an actor, I could think about the character and the character’s life. And that opened a new horizon for me.”

By the time she landed in New York, after finishing high school in the late 1950s, she was primed for the city’s heady mix of bohemian life. Whether you set your sights on acting, dancing, music, or art, there was no lack of opportunities, and affordable rents still made the city a mecca for creative types. “I studied dance and method acting, went to the Met Museum almost every day, painted, auditioned, worked at a myriad of temporary jobs while simultaneously landing work as an actress and dancer Off-Broadway and in experimental film, television and movies. I played the student in Ionesco’s The Lesson while my paintings exhibited in East Village galleries. And then there were all those mandatory coffee-house discussions on ‘the meaning of life.’”

“Visual Art was always a constant,” she adds. “In between jobs, either dancing or acting, I was always painting.”

In 1962, she married a fellow actor and moved to Los Angeles to work in television. The couple found an affordable house in Laurel Canyon, and then, as she puts it, “life started to intrude.” Leis had two children before the marriage started to unravel, and then, still in her twenties, she found herself a single mom with no college degree and not much in the way of prospects for steady employment.

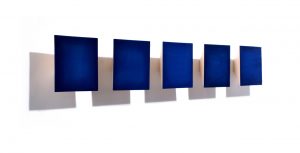

Convergence/Sublimation (2016), installation, various sizes, Styrofoam/cover stock/MDF/oil and cigar boxes/acrylic (inspired by winter residency in Iceland)

She put together a natural childbirth course and started teaching in a hospital, and then after a friend gave her Arthur Janov’s The Primal Scream—an introduction to a new kind of therapy that became hugely popular in the ‘70s—she got in touch with the author to describe her observations about birth trauma. He asked her to write a chapter for his next book, and within a year she was on her way to becoming a primal therapist, earning a bachelor’s and a master’s in psychology from Antioch University West.

Throughout her years of studying and working in L.A., Leis continued to paint, and by the time her kids were ready to leave the nest, she decided she wanted to devote the next stage of her life entirely to art. New Mexico seemed like a good place to start the next chapter, and after seeing an ad in the Los Angeles Times for a house in a little community south of Albuquerque, she headed east. Mountainair, a town with about 1200 residents, looked too rural to her, but she explored Santa Fe, Albuquerque, Dixon, and Taos, and found a house for a couple of years in Ranchos that seemed ideal for her purposes. “Then I really decompressed,” she says. “I was working every day, and confident about the work I was doing.”

Green: Abundance and Scarcity (2014), installation of “Seed” paintings, oil/paper/wood/gold foil, various sizes (inspired by a residency in Thailand)

But at the end of that period Leis decided it would be a good idea to return to school for an MFA degree at the university in Albuquerque. She interrupted her studies midway to go to spend a year in Perugia, studying Italian at the niversity “because that’s my family background,” she says, “and I was also very interested in Arte Povera. Luckily I was able to meet Mario and Marisa Merz and Alighiero Boetti, whose generosity was truly inspiring.”

Flying back from Italy, on the leg from L.A. to Albuquerque, Leis met her second husband, David Vogel, a management consultant who now devotes much of his time to photography. Throughout the years in Los Angeles and New Mexico, the artist says her work was “very fractured and complex, every square inch filled with something, but then as things evolved, it just started emptying out. I started being more interested in space and form.”

A major turning point occurred during a residency at Crater Lake, OR, in 2001. “There I awoke each day to see the deepest, bluest lake in North America,” as she writes on her website. “It brought to mind my profound experience of Maya Lin’s Vietnam Memorial, where I felt I became part of the sculpture as I descended down its walkway. Crater Lake helped me to understand viscerally how to make paintings that would dissolve the boundaries between the viewer and the painting so that people could ‘enter’ my work.”

In conversation she calls this a “very primordial experience, completely bypassing the intellect.” At first her paintings about the Crater Lake experience had edges—”as the sunset reflects in the waters, as the water laps toward the shore. Then I just dared myself to take away the edges, and that’s when they became just about color and place.”

In the last 17 years, Leis has traveled widely and spent a great deal of time in residencies, where a single color might provide the inspiration for an entire body of work. A series called “Atmospheres” reflects a stay at the Cawdor Estate in the Scottish Highlands. “As I looked from my cottage-studio window the sun winked now and again, lighting the skies with wondrous sunsets of lemony and cadmium yellow and fuchsia pinks,” she writes. “The days were pregnant with every gray color value and the nights were like black velvet. The scenic beauty that could be both dramatic and soft as cashmere fascinated me as I hiked the hills, moors and river valley.”

Similarly, a need to feel grounded led her to an artist-run residency in a remote corner of Thailand ( Compeung in the Chiang Mai province) and resulted in a series of sculptures, paintings, and photos exploring the humid and tropical essence of the experience, mostly through the color green. “I try to be in or near a small town or village, where I can meet people, because that gives me a greater sense of place.

Symbiosis 1-2/Traces1-3 (2018), oil on linen, part of a new series “Engrained: Ode to Trees,” 60 by 40 inches

“I also travel a lot outside of residencies,” she adds. “I ask myself, What would it be like to spend 30 days in the forest? Or 30 days in the Arctic Circle? That’s the basis of what I seek out, the environment.” A series of works at the Harwood Museum in Taos (through October 8) explores what it was like to be in Laugarvatn, Iceland, a place that’s dark almost 24 hours a day in winter.

“It is antithetical in our everyday life to slow down, but I am committed to this process in creating my art,” Leis writes in one of her artist statements. “Restraint is a key factor in my work as I include only what is essential for the optimal taste and visual experience.”

When people ask about inspiration, she says her work “is almost always influenced by the environment, not by art or the art world. And it’s about stretching myself—there’s always some new medium I want to try.”

Marietta Patricia Leis exhibits widely in the U.S. and internationally; her works will be at the 2019 Venice Biennale and at the Mark Rothko Art Centre in Latvia (July 6 through September 8, 2019). More about the artist can be found here.

Ann Landi

Top: An installation (2017) inspired by Leis’s residency in Iceland

Ann–Your piece beautifully captures the essence of who I know Marietta to be and what her art-making is about. Thank you for such an articulate expression of this complex, diverse and intelligent woman who I’ve been madly in love with ever since the day I watched her walk onto that flight from Los Angeles to Albuquerque. /d

What an informative review. I appreciate the explanation of the progression of Marietta’s work to what we see today, and the background/context that informs my current rich experience with it. Big fan.

This is a remarkable story of the artist who makes this beautiful strong work. As is so often the case, the richness of the path and the richness of the work.

I think I have one of her personal sketches, I think it’s called clown break. by chance anyone might know how to find out who it might be the sketched it. It’s old found in mothers’ stuff after she passed, and I’ve never seen it before .