Artists reflect on changes, shifts, departures, and continuity

I’m fairly sure it was Chicago artist Sharon Swidler who mentioned a year or so ago that she was riffling through her inventory and remarking on the absence of abrupt departures in her work. I tucked the idea away for a future post—what do artists gain from looking at past work?—and now seems the ideal time to investigate the subject further. So I asked around a dozen (and could have asked many more): What changes do you see when you look over a few decades of making art?

Responses tended to fall into two or three camps: artists like Laurie Fendrich, who describes herself as a “slow painter,” and has experienced only a few shifts in the many years of her long career; artists who have experienced a need for radical departures; and those who can return to earlier works and happily pick up the threads of ideas forgotten or abandoned.

The pandemic, which has entailed stasis and self-isolation for so many, seems a perfect time for looking back. Below are nine who reflect on the particular pleasures of retrospection

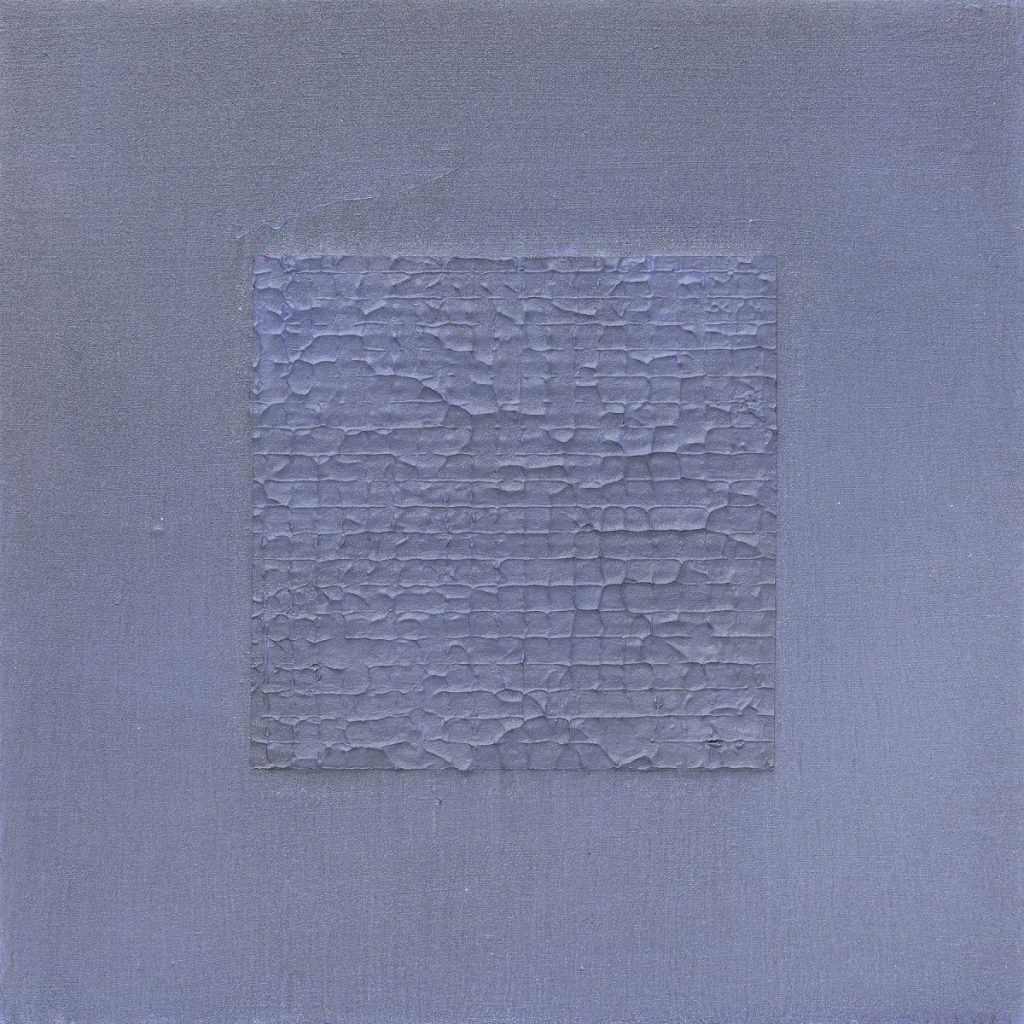

Sharon Swidler

I have been going back and redocumenting a lifetime of old paintings and drawings, hoping at some point to sell them at an open studio. As artists, I think we all want to grow and develop, and there’s that “aha!” moment of discovery—of finding a new idea, a new way of working. What I’ve realized in going back through my work is that I’m exactly who I’ve always been. I’ve had moments of shock when I started something new, and I’ve thought, “Oh, wow! I’ve had a breakthrough.” And then I go through a portfolio and I find something identical that I did 20 or 30 years ago.

I never expected in graduate school, where I was smitten with works by painters like Susan Rothenberg and Franz Kline, to evolve into the kind of artist I am now. That is, predominantly a minimalist. There’s a consistency to my work, to the format and the colors I choose, and the degree to which that happened is surprising. It’s also very reassuring to me. People might see that as limited, but I don’t.

Christopher Benson

I tend to veer between realism and abstraction and have repeatedly bounced back and forth from one to the other of those extremes over the years. I did Hopper-like figurative paintings for a long time, then took a radical turn and went wholly abstract. Somewhere in there I veered back into a kind of invented, landscape-based expressionism. These cycles have repeated several times in my life as a painter

Recently I looked at a body of work that I did in my thirties, in the mid-1990s. These were all landscapes and coastal scenes, and mostly imaginary places. Earlier this year I went back to those works to jump-start a new run of a similar kind of invented subject matter, and also to explore the more expressionistic, painterly approach I’d used at that time.

Revisiting the old work was a way of getting the ball rolling and saying, “Okay, I’m not going to do this radically abstract work, or the realistic work. I’ve got to find a place in the middle.”

The Basin is a straightforward copy of a detail from another large landscape from 1994, but with some altered areas in the foreground. Big Sky, which is a recent small canvas, is based on an even smaller painting—Thunderstorm, from 1997—but rather than being a direct copy, it’s more of a variation on the original theme.

I’ve tried a lot of different approaches in my career. But at this point, having just turned 60, I’m simply looking for the language that is the most satisfying to me, and which combines the best aspects of all the many paths I’ve traveled. (Editor’s note: Several of Benson’s works, including The Basin, can be seen at Evoke Contemporary in Santa Fe through the end of the month.)

Christine Aaron

Art is a second career for me. When I began more than 20 years ago all I wanted was to master my materials and paint evocative landscapes. It wasn’t long before I wanted to create work that offered more than the image itself. Themes of memory, loss, time, and the fragility of human connection crystallized early on, and these have remained my focus ever since.

I gravitated toward tree imagery as a metaphor for humans. Trees mark their experience within their rings much the way humans are marked within by emotional, physical, and psychological experience. I wanted my materials to be more visceral, serving as meaningful contributors to the themes I was exploring. I started printing on aged mirror and patinated metal, reflecting the tangible marks of the passage of time; and I printed on transparent gampi panels, through which one could walk as if through life’s experiences and memories. This installation also included an audio component.

Through continual viewing, reading, and professional critiques about art, I have realized that art is part of a larger cultural conversation. When I first began, I was trying to guide the viewer to a specific meaning. Increasingly, I am using materials such as tree slices, shattered mirror, nests, dyed cocoons, books, and handmade paper, with their own rich histories and associations. These are tactile and evocative but leave the interpretation of the work more open ended, even more so than my intermediate materials of patinated metal, aged mirror, and gampi. I have come to believe that there is truth in the making itself, and I employ processes that contain and point to content, meaning, and concept. The through line all these years is to create art that explores memory, loss, and human connection in ways that allow the viewer to respond with curiosity, the intellect, and the gut. My art has grown over the years in exploring these themes less rigidly and literally, with more flexibility and respect for the materials and the individual human experience of the art itself.

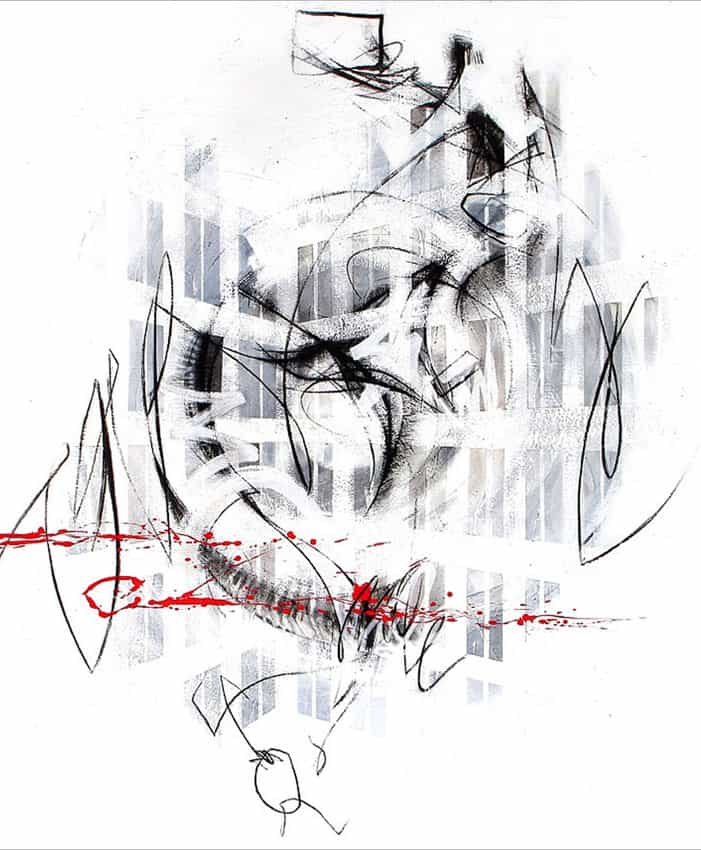

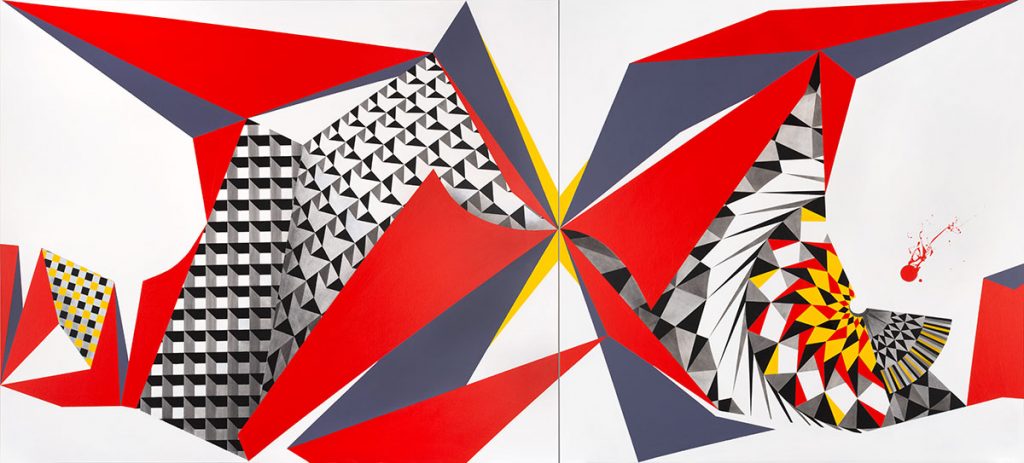

Jane Barthès

Last year I gave a talk about my work at Fermilab in Chicago and found myself looking to explain how on earth I have evolved from a comic strip in the 1980s, through figurative painting and on to the geometric, urban abstract shapes that define my work today. It has been quite the journey; an intensely personal one that involves considerable travel and living around the globe. Each port of call has been an opportunity to integrate new ideas and cultures. However, regardless of the visually quite different phases of my work, I was struck by the underlying coherence in thought and practice. Themes can come and go and get explored in a myriad of ways, but there are two profound motivations that remain at the core.

I discovered drawing and energy are my immutable themes, or obsessions that nurture my entire journey. I almost feel as if I have an informal PhD in drawing, having spent my life deconstructing and reconstructing all I know about it to better understand the notion of the abstract in order to reconstruct form in new ways. Drawing has always been the main tool through which I explore every phase and development in my work and my life. Beyond using drawing as a tool, the actual process of drawing became fascinating to me early on and lead me to the philosophy of Zen. I came to realize that in the act of drawing there was no separation between me, the object of my art and the canvas. I became one with everything. I have been developing this intuitive experience and way of working ever since.

Throughout my work, there is also an undeniable, almost overwhelming core of energy. I have always been intrigued by the intangible quality of energy that propels me through my existence. I try to understand it without wishing to pin it down or own it. I am guided by a sense of the esoteric connection between all things. Quantum physics, String Theory, geometry and architecture have all come together to build and contribute to an abundance of layers accumulated throughout my life, but when I look back, I see that drawing and energy are always at the core of everything I create. I hope they contribute, in a fresh way, however humbly, to the major conversations and disciplines I engage with in my practice

Christopher Rico

There are two ways in which I tend to encounter my previous work. The most common is usually tied to relocating my studio, and the other is seeing the work in situ. The latter is disappointingly infrequent, but it tends to be more arresting because of context. The former will often send me into multiple days or even weeks of introspection as well as retrospection.

It’s easy to see unifying themes, and even recognize a persistent (if at times emerging) visual vernacular. I confess I’m always a bit surprised to discover that old work still retains my hand in a recognizable way, no matter how long the journey from it may seem. Hindsight, they say, is 20-20, but the human ability to forget even the most traumatic of historical events very quickly makes me skeptical that I’ve consciously built on my own past. Looking back upon the road traveled through my paintings and assemblages, it is tempting to construct a cohesive narrative. Like curating those Instagram photographs before posting them, I can easily believe that version of the truth; that what I was doing in 2010 or 2001 somehow foretold the paintings in my studio now, but that is both disingenuous and revisionist. The truth is I’ve wandered and explored and gotten lost and found my way back countless times, and I intend to keep doing so.

As artists, we train ourselves to see and not merely look. Seeing older work is like finding old letters. They are moments frozen in time by another self—a younger self from a different era with a different soundtrack. I like to run my hands across old surfaces, perhaps to glean some muscle memory wherein I can inhabit that previous self, if only for a moment. In one’s studio, there are the intimacies of proximity and reference.

I moved into a new studio on March 1 of this year. After the initial quarantine, I’ve spent some time in the space reflecting on and revisiting old works, and they are helping me find a new direction. Representatives from abandoned bodies of work, in some cases unresolved, in some cases simply something I needed to move on from (and occasionally something that I wonder why I didn’t do more of), stand as witnesses to persistence, tenacity, and what my wife simply calls stubbornness. Incorporating what I see into the sketchbooks and working through the ideas and associations has been one significant way I’ve coped with all things related to this pandemic.

There’s value to looking back. I’m no futurist. I just don’t like to stay in the past too long.

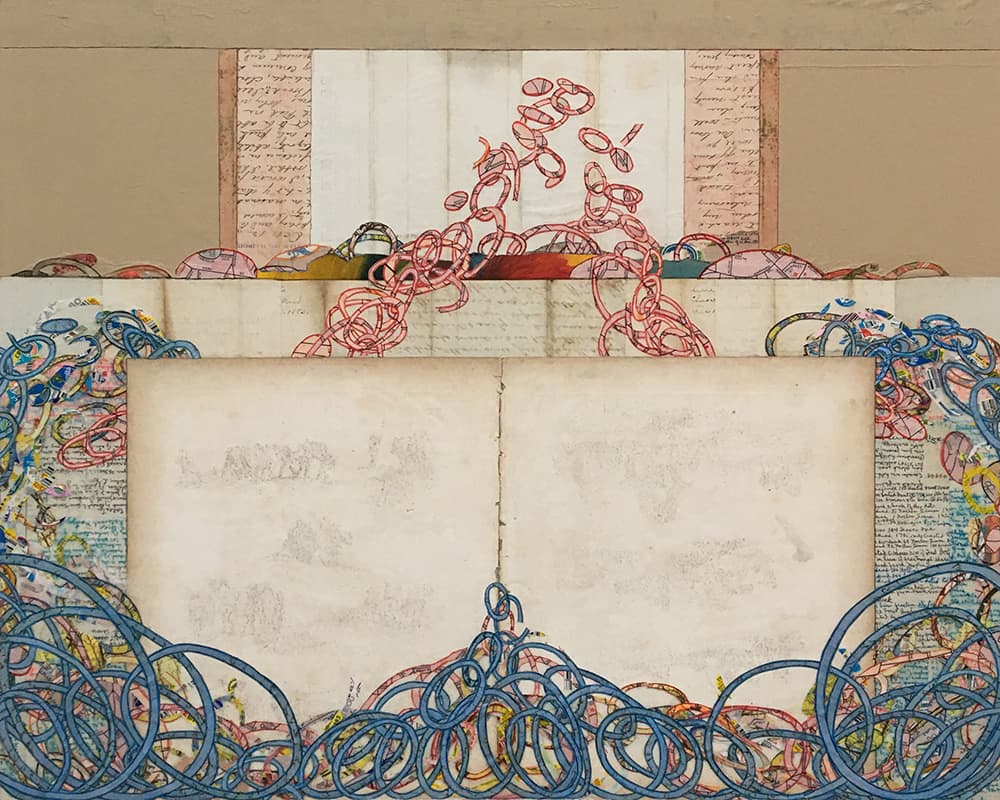

Jemison Faust

Cleaning out the studio as well as purging art files has turned out to be a fine time to check on my long journey as a visual artist.

Over the years the work has ranged from clear realism to process-based abstractions. Settling into one or the other has always seemed totally out of the question, but it did give me pause at times when the visual thread seemed tenuous at best.

Yet, looking over the span of years, there now seems to be much more conceptual consistency and an actual process in my brain that begins a new series. Who knew? There is always some small object (a 200-year-old letter, the separated foot of a doll) or some place (a room full of frightening detritus or the TV operating room where beauty is “restored” through plastic surgery). Some kind of emotional resonance gets triggered in me from these objects or places and off I go down that wonderful path toward creating my version of what it is all about. Mostly I just want to see what I am thinking about and so I have to actually make it. The hardest work I have ever done, but what a life-long treat.

Laurie Fendrich

Over the years, through a natural attrition that probably came about because I moved around so much, I lost almost all the paintings and drawings I made from undergraduate

through graduate school. Although I held on to work starting in the early 1980s, the work I made in that decade seems jejune and derivative to me, and I’m not interested in it. Around 1990, however, I suddenly, on impulse, introduced ovals and curves in my work, which I had never done before. For a slow painter like me, who paints at a turtle’s pace, this was an enormous swerve away from the direction in which I’d been mindlessly heading. I see now, with the clarity that comes with time, that it was then that I hit my stride. All the paintings and drawings I’ve made since that first little oval continue to resonate with me, and looking at these older paintings gives me ideas for new ones. Recently, I pulled out a 20-year-old painting from my storage racks and happily hung it on a wall in our living room. I see it every day now, and the oddest thing is that I could have painted it yesterday. An artist I once knew told me that painters are lucky if they come up with one good idea in their lifetime. At the time, I dismissed the comment as patently ridiculous. It turns out he was right.

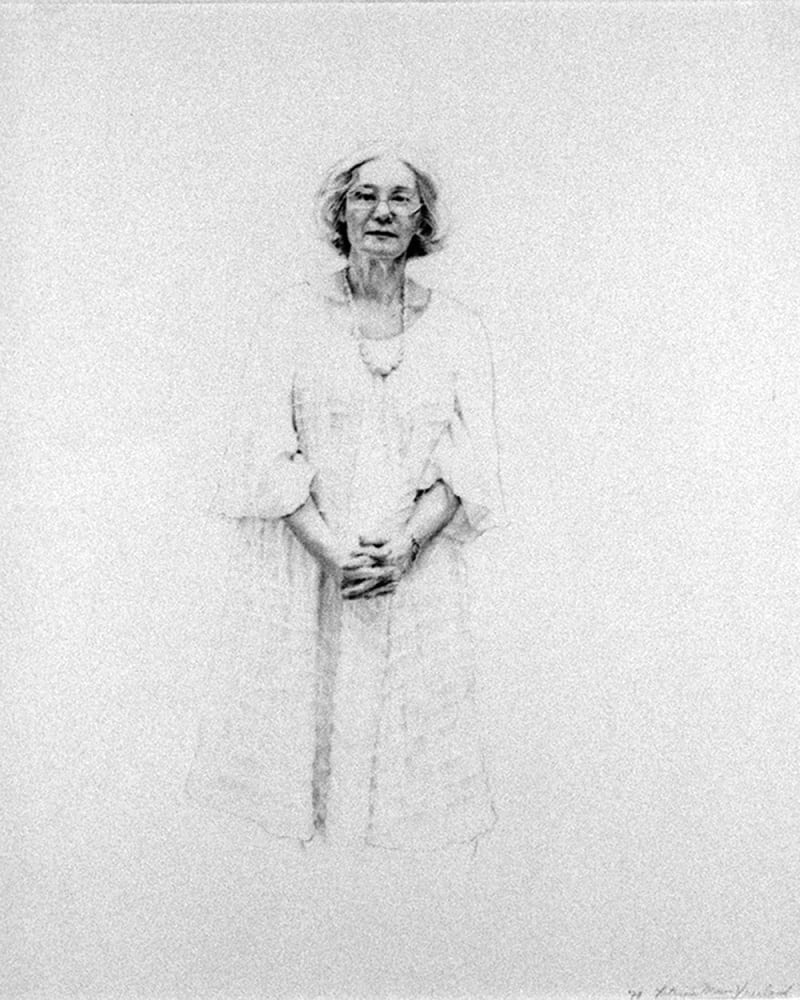

Patricia Moss-Vreeland

I started out as a draftsman and painter of still life and figuration, and had a successful 20-year run of gallery shows in Philadelphia. Two qualities that were important to me were composition and a sense of stillness and order. Art at that time provided moments of contemplation within my personal narrative. But there came a point in the early ‘90s when I wanted to branch out and aim for a bigger permanent space. My husband, sculptor Robert Moss-Vreeland, and I applied to and won a competition to design the Memorial Room, Holocaust Museum Houston, which consumed three years of our lives and became a place to address remembrance. Right after the museum opened, I found it difficult to return to the routine of having gallery shows. I was searching for a transition. I had lingering questions about the process of memory, experienced so differently by survivors, and this became important to me, as it also dovetailed with my own memory of losing my mother when I was 25.

The relationship between memory and emotion propelled me into science and learning about the brain and the construction of memory. I was led into research, starting a book, and then on to my next show, a collaboration with a neuroscientist in a nonprofit space, the University City Science Center, EKG, in Philadelphia, about memory as a subjective process, placing it both in the realms of science and of art.

In my poetry and in my art, I’m always looking back in ways that deal with memory. I’ve devoted the last 25 years, first with the design of the Memorial Room, to exploring the mysteries of the brain and memory in a multi-sensory art and science installation, interspersed with authoring a book, A Place for Memory: Where Art and Science Meet, and other exhibits, projects, and events that deal with the social impact of memory.

I’ve always drawn, and that forms a daily practice since I was a young child. It’s a way for me to process, and a form of meditation. I have started working with still life again. I enjoy revisiting pieces from my past, as they create a link to my memory, and how things have evolved. Because of the isolation, I found we have a chance to be quiet, to think about where we are, what’s happened in the past, and we’re going. My still lives are about that—a stillness.

Adria Arch

I have often been struck by how many times I seem to circle back to familiar elements in my work. I’m definitely not an artist who stays in her lane, repeating the same work over again, but there are several threads that I see myself following through the years. For example, I seem to gravitate to the close-up view with no horizon line, a kind of “in your face” perspective. I have a fondness for the rounded, organic shape as opposed to the architectural. I’ve always been drawn to energetic work by artists like Frank Stella, Elizabeth Murray and Judy Pfaff. I am excited by three-dimensionality and by the cross fertilization of dance, poetry, music, and visual art.

For instance, a piece from 1987 is sculptural but still painting, with dangling appendages, and is a precursor to a piece from 2018 that recently hung in my exhibit, “Reframing Eleanor,” at the Fitchburg Art Museum in Fitchburg, MA.

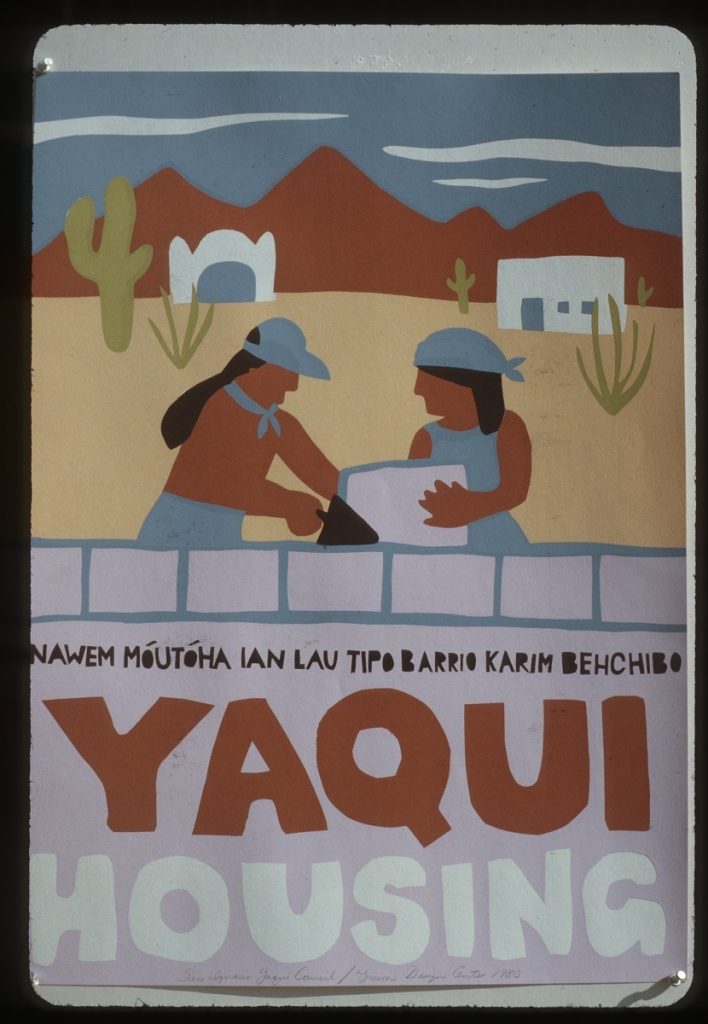

The poster about Yaqui Indian housing rights in Tucson, AZ, from 1980, makes me think about my very recent installation at the Cahoon Museum of American Art on Cape Cod, echoing the shapes and colors I used so long ago.

When I started my most recent series of installations filled with swooping painted plastic shapes, I so wanted to see them move, but at first I couldn’t imagine how that would happen. So I sought to collaborate with dancers and a musician to animate the space around the pieces. It was thrilling to work with my collaborators, and the experience allowed me to see so many possibilities. That very successful experiment reminded me of my work as a graduate student in art education at the University of Arizona in 1979. I created a project to enhance the museumgoer’s understanding of several art works in the university art museum, including a Rothko, by pairing the art work with poetry and dance performances.

I feel that if an artist tracks her work over a lifetime, it isn’t at all surprising to notice many similarities and connections.

Top: Adria Arch, “Interfence,” installation at Cahoon Museum in Cotuit, MA, on view through December 2020

Such a wonderfully evocative and timely question you pose for artists. Thank you for asking me that question and including my response. I so enjoyed hearing from all these diverse artists, their true reflections and approach to their art.