By Ruth Hiller

It’s probably difficult to pinpoint the very first artist to make a shaped construction, an artwork that hovers somewhere between painting and sculpture. The possibilities for non-rectangular paintings begin as early as the 1920s with fanciful polychromed wood reliefs by Jean Arp (one dating to 1917 can be found in the Museum of Modern Art’s collection). A Wikipedia entry on the subject cites such now-forgotten figures as Abraham Joel Tobias, Rod Rothfuss, and Rupprecht Geiger from the 1940s. Closer to our own times, and far better known today, Carmen Herrera, Ellsworth Kelly, Elizabeth Murray and Frank Stella literally broke boundaries by creating outside the rectangular box.

This exhibition, following on the precedent of Robert Straight’s selection “Is It Frankenstein?” from last summer, brings together a selection of six artists, all of whom are members of Vasari21, whose work expands the constraints and parameters in contemporary painting. Encompassing a formidable array of materials—from plywood and Lucite to traditional mediums like oil paint and canvas—the constructions of Ruth Hiller, Rachel Hellmann, Mokha Laget, Michelle Benoit, Paul O’Connor, and James Austin Murray shift our perceptions of what a painting—or even a sculpture—should be. By testing the boundaries, they continue to open up the possibilities for art in the 21st century

Ruth Hiller

Hiller began using soft rounded panels six years ago, as a way to break out of traditional confines. Like Michelle Benoit and Paul O’Connor, she works with plywood, once considered mainly a building material, but now increasingly called into service by artists. The wood grain, along with her brightly painted surfaces, is an active participant in creating a sense of movement. “Color, Minimalism, science, and mathematics have interested me throughout my painting career,” Hiller says. “My use of materials is the unifying thread that ties these concerns together. I am a surface fetishist.”

Michelle Benoit

In Benoit’s reductive and luminous constructions, her color choices reference memory, personal experience, and a sense of place—she describes the work as a “tangible remembering,” says the website for McKenzie Fine Art, where she was part of a three-person show last summer. “In this new series ‘Laminae,’ the artist’s process is akin to a geologist gathering core samples of the earth. Benoit, based in Providence, RI, literally excavated the walls of her childhood bedroom. The palette choices in her sculptures were derived from the layers of paint and wallpaper she discovered in the core samples, which are recreated with acrylics, gouache, and other pigments and forever preserved under reclaimed bulletproof Lucite.”

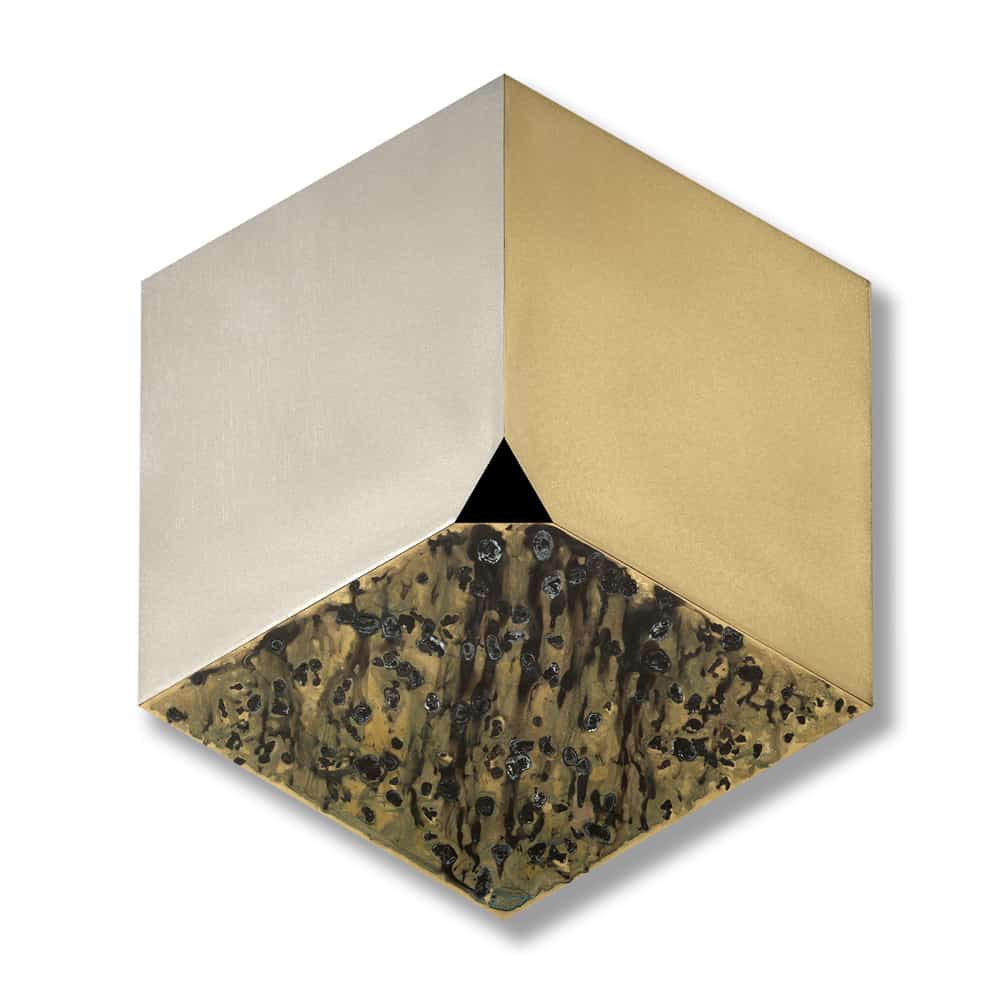

Paul O’Connor

Trained as a photographer and well known for his portraits of Taos, NM, luminaries like Agnes Martin, Ken Price, and Dennis Hopper, Paul O’Connor turned to sculptural constructions in the 1990s. He has developed an idiom in the Minimalist tradition, using a few basic shapes to create wall-hugging “reliefs” made from wood, aluminum, stainless steel, and other materials suggestive of both the natural and the industrial world. The artist’s introduction of unusual woods—like purple heart and leopard wood—along with rusted steel, copper, and highly polished brass give the works a lively painterly surface, even though paint is never part of his vocabulary.

Rachel Hellmann

Hellman works in bright acrylic hues on solid poplar wood, whose painted folds may remind the viewer of multi-colored origami. The lights and shadows open up different interpretations, depending on where the viewer is standing. “Drawing has always been the backbone of my studio practice,” says Hellmann. “It is the place where ideas are generated, space and shape are explored, and color relationships are introduced. My approach to the works on paper is fluid, immediate and exploratory. Some of the painting moments in these pieces seep into sculptural pieces and others will be happy to remain in the two-dimensional world.”

Mokha Laget

About 10 years ago, Laget turned to shaped canvases incorporating hard-edge color fields to create more dimension in her work. The artist can trace the beginnings of her fascination with geometry to her upbringing in North Africa, where remnants of ancient Islamic and Roman civilizations are still evident in mosaic floors and architectural ornaments. Her affiliation with Gene Davis as a student at the Corcoran in Washington, DC, set her on the path to becoming a professional artist, and relocation to Santa Fe 20 years ago opened up her practice in ways she is still exploring.

James Austin Murray

Relying on the most basic of means—ivory black oil paint, canvas, and a wood support—Murray uses up to nine wallpaper brushes affixed to a long handle to create magically undulating surfaces. The striations from the brush take the eye on a roller-coaster journey into pleats and folds, over light-struck hillocks and into shadowy crooks and bends. Depending on where you stand, the paintings look like a forbidding landscape you could walk right into. In the last couple of years, Murray has been experimenting with tondos and large, asymmetrically shaped canvases, which continue the journey into ever more intriguing territory.

Sorry to to just be catching up on all the Vasari21 posts now! Beautiful job Ruth Hiller!

Just saw this! Congratulations, Ruth! This work is so colorful and dynamic that it breaks off the wall into living and breathing space. Such fun to see it together!