Even the Most Respected Critics Change Their Minds

When a politician flip-flops on a position, the public and press alike are quick to cry foul, hurling accusations of bad faith or pandering. But when an art critic changes his or her mind, the ripple effect is likely much smaller, piquing the attention of only staunch loyalists, other critics, or the artist in question. Nonetheless, when venerable critic Peter Schjeldahl’s blog post titled “Changing My Mind About Gustav Klimt’s ‘Adele,’” appeared on the New Yorker’s website in June of 2012, we took note. Schjeldahl did not so much do a complete about-face on the glittering 1907 portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer, the 25-year-old wife of an Austrian industrialist. He downgraded it from a work of art, which he’d called “transcendent in its cunning way” six years earlier, to a “largish, flattish bauble . . . classic less of its time than of ours, by sole dint of the money sunk in it.”

“I’d kind of given it a pass the first time around,” Schjeldahl says. “After seeing it repeatedly for many years, I decided, ‘This is a mess.’ The first impression is that it’s absolutely gorgeous. But now I find it too incoherent to qualify as good painting or even as good decoration. That it was the most expensive painting in the world at the time is depressing.”

Schjeldahl’s admission led us to wonder about other art critics who have altered or even totally upended their judgments in print. How does this happen with a person who supposedly has smart-enough eyes to operate as a critic in the first place? Does the mood of the times influence their tastes? The high or low opinions of other critics? A lack of familiarity with a given medium or artist? And what do critics say of other critics who change course?

“Behind Peter’s blog post, I think, is a disgust with the impact of grandiose money on esthetic judgment and experience. That disgust to some degree determines how he sees the painting,” says Michael Brenson, who spent nine years as an art critic for the New York Times. “It’s an admission that the context in which a work is seen affects what you actually see.”

Donald Kuspit, an author of numerous books on artists and art criticism, had harsher words: “Schjeldahl’s remark about Klimt’s painting doesn’t seem well considered. It’s more of a snap judgment than an argument, which is what a critical evaluation should be. It should also be more art-historically informed. He might have compared other Klimt portraits to the portrait of Adele. His unsubstantiated opinion—which is what it is—might then have credibility.” (Kuspit himself was once a great admirer of Leon Golub and wrote a book on the painter in 1986, but began to lose interest in the artist’s later works, saying that “in the end his political correctness became more important to him than painting.”)

Late Monet: Style but not Art

In the long and mostly unexamined history of critical flip-flopping, Clement Greenberg’s judgments about Monet may rank as one of the top ten reversals of all time. In 1945, Greenberg dismissed the Impressionist master’s late paintings as “mere instances of his style but not works of art.” Twelve years later, notably after the achievements of the Abstract Expressionists, he could proclaim their revolutionary significance: “the righting of a wrong is involved here, though that wrong—which was a failure in appreciation—may have been inevitable and even necessary at a certain stage in the evolution of modern painting.”

“Excuse me? That’s like a politician saying Mistakes were made instead of I blew it,” wrote critic Terry Teachout in a 2002 essay that revealed his own wrong-headed assessment of a Mark Morris ballet. “I’ve changed my mind many times and feel that it’s important to admit that you did instead of trying to pretend you always felt that way, as many critics do,” says Teachout, who has written about art, theater, and dance, most notably for Commentary and the Wall Street Journal. Teachout experienced his own reversal on Monet, finding him “great” at first, but then deciding the paintings “eventually went dead on the wall for me.” After years of writing reviews, he says that he has learned to become wary when he has a strong negative reaction to something. “When your first encounter with a work of art produces a powerful negative reaction,” he says, “you mustconsider the possibility that in fact it’s a positive reaction and that you’re misinterpreting because you’ve been so jolted.”

Irving Sandler, well known as a champion of Abstract Expressionism and the author of The Triumph of American Painting, admits that when he first saw the works of Frank Stella and Andy Warhol he was completely baffled. “Here I was, identified with the avant-garde, unable to immediately accept what was new,” Sandler says. “Did I love Andy Warhol in the same way I loved de Kooning? No. But I certainly recognized his enormous importance and the way in which he is relevant today. And since then I have been very, very careful. When something really strikes me in a negative way, I’ll give it time.”

Some critics chalk up their inexperience with entire genres for judgments that later required adjustments. Not long after landing in the Bay Area more than three decades ago, Kenneth Baker, former art critic for The San Francisco Chronicle, was invited to give a talk on photography and confesses that he “essentially wrote off the whole canon,” at the time. “But soon I made two discoveries—that there were a lot more photographs out there that I admired for various reasons, and that photographs are easy to write about because they are rife with content.” These recognitions led Baker to explore the medium more deeply. “I found myself fascinated by the work of photographers as different as William Klein and Irving Penn, Lee Friedlander and Joel-Peter Witkin.”

Bad First Impressions

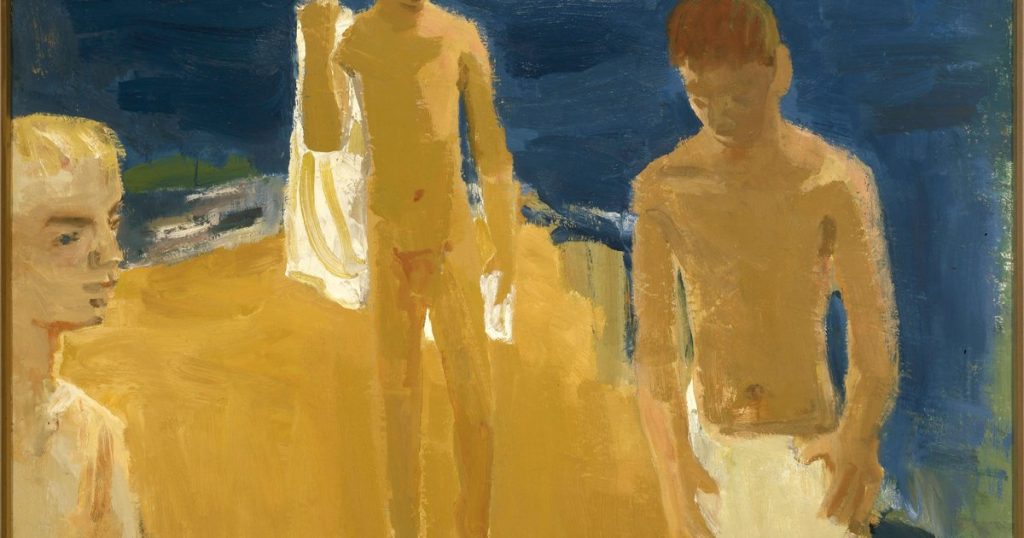

Sometimes, the initial experience of an artist’s work provokes a negative reaction in print, but more sustained exposure leads to an appreciation of his or her achievements. “The first time I saw David Park’s work, which was in 1983, I wrote a short, fairly negative review. By the time Park had a retrospective at the Whitney, I loved the work,” says Brenson. “Barbara Kruger was another one. The first few times I saw her work, I wasn’t that taken with it. I came to love her work as well.” When Kim Levin, another ARTnews regular, was writing for the Village Voice, she strongly urged viewers to “boycott” John Currin’s first show, appalled at his depictions of older women and calling the paintings “awful.” Later, on seeing his 2003 retrospective at the Whitney Museum, she did not entirely reverse her initial dislike, but expanded on her reservations while lauding his “courageous stance” and calling him our era’s “premier mannerist.”

Similarly, Christopher Knight, critic for The Los Angeles Times, remembers admiring but ultimately dismissing Nancy Rubins’s Trailers, Drawings and Hot Water Heaters from the landmark group show “Helter Skelter: L.A. Art in the 1990s” at the Museum of Contemporary Art. Her “mountainous pile of wrecked mobile homes and ruined water heaters startles with blunt force, but little resonance follows the initial, gee-whiz impact,” he wrote in 1992. And yet 16 years later he disclosed that he found it impossible to put the work out of his mind: “A sculpture I can’t forget is one I criticized as unmemorable.” When Rubins installed a monumental piece in MOCA’s plaza, Knight called it a “strange and formally beautiful force-field” that “gives me a thrill every time I walk by.” The lesson from the 1992 review “is fundamental,” he wrote. “Art is experience, which needs to be trusted as it unfolds. The better part of criticism is in understanding that.”

A prime example of an almost seismic shift in opinion occurred after “Picasso: Mosqueteros,” a show of late Picasso paintings at Gagosian Gallery’s Chelsea outpost in 2009. Eminent critics like Robert Hughes and John Berger had dismissed the paintings from the master’s final years when they were unveiled in exhibitions in the early 1970s. “It seems hardly imaginable that so great a painter could have whipped off, even in old age, such hasty and superficial doodles,” Hughes wrote in Time. A decade later, after the Guggenheim’s 1984 retrospective, he began to relent: “the good ones are so good, and in such a weird way, that they utterly transfix the eye.” And by the time of the 2009 survey of over a hundred works from 1962 to 1972, more than one critic was munching on a little crow. “Some of us condescended to the last phase of Pablo Picasso’s career, dismissing it as lazily slapdash,” wrote Schjeldahl. “We ignored who we were dealing with. . . . Ahead of his time yet again, Picasso anticipated generations of painters who have roughed up the medium in order to resuscitate it.”

The sociopolitical temper of the times inevitably has an influence on critical judgments. “I’ve been instructed a bit by feminism and identity politics,” says Peter Plagens, who has been a critic for Newsweek and the Wall Street Journal. “Lee Krasner was overlooked and underrated, and the most jaw-dropping show I’ve seen in recent memory was the Lee Bontecou retrospective at MoMA-in-exile. She should be right up there with Johns and Rauschenberg.” Plagens recalls having changes of heart over the years about Helen Frankenthaler, Francis Bacon, James Turrell, and Robert Irwin, among others.

Then there’s the problem of too much hoopla surrounding the debut of a new artist. Peter Frank, a Los Angeles–based critic who has flip-flopped notoriously on Mark Kostabi (loving, then hating, then loving him again), says, “I’m always suspicious of my own suspicions. When somebody comes along and everyone makes a big deal, that always puts me off slightly, even if I’ve been enthusiastic myself.” Adds Plagens, “Most of my changes of mind—or changes of heart—concern something that I see in a gallery show that strikes me as really snappy, only to have it seem more superficial as time goes by.”

“To me there is a difference between a reaction and a response,” says Brenson. “A response is more what I’m looking for. Understanding what you’re looking at is really a precondition for making a judgment about it. Sometimes that understanding can take time—it can take years to begin to feel you ‘get’ an artist. For years, I could not respond to Bruce Nauman. I knew that the problem was mine. With more knowledge, more exposure, more time, one changes. A charged receptiveness becomes possible.”

But no matter what the judgments over the long haul, most critics agree that it’s important to be careful about the targets of negative reviews. “There’s a natural reluctance on the part of critics to say out loud that somebody they might know in the flesh has gone downhill. Part of that is because most artists, even famous and successful ones, suffer real damage from critics’ opinions,” says Plagens, who’s an artist as well as a critic.

“One thing I learned at ARTnews, where I was a critic from the end of 1956 to ’62,” adds Sandler, “is you always hit the big guys. You never hit a little guy. You simply walk away from those who are incompetent unless they’ve achieved some reputation worthy of being hammered.”

Ann Landi

Top: Gustav Klimt, Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1907)