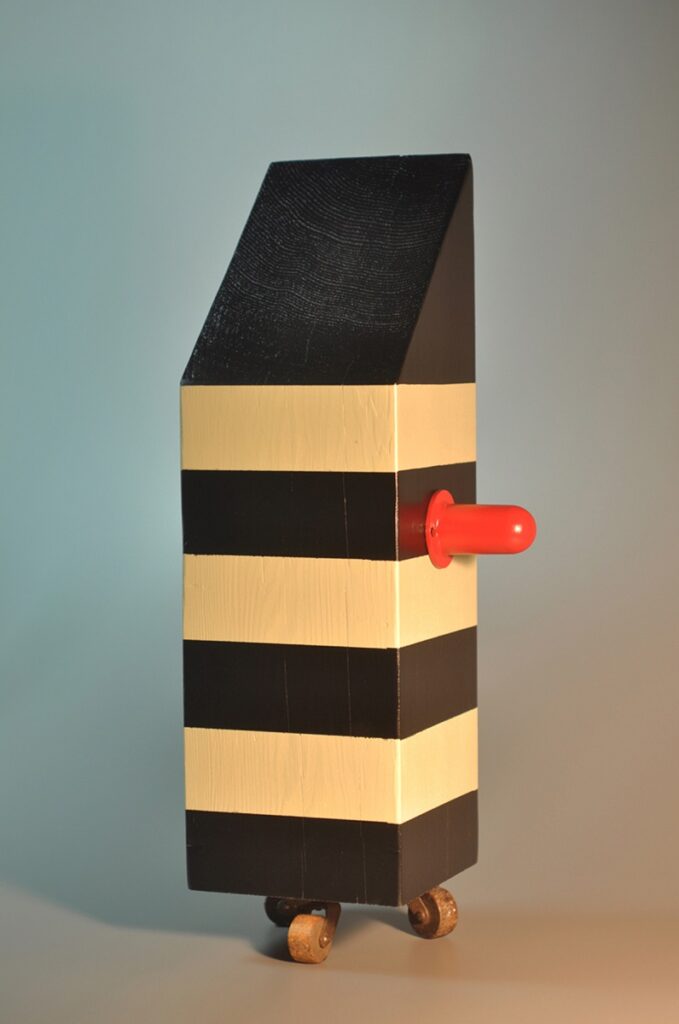

Cindy Blakeslee’s sculptures startle with unexpected collisions of found objects: Nails bristle, almost angrily, from shapely chunks of wood. Papier-mâché eggs lie cradled in a nest of shredded maps, suspended from delicate chains. A marbled rock supports a pewter-colored lightbulb, cast in concrete from a real bulb, which is gracefully encircled by a bracelet of steel. Some of her source materials are obviously industrial, but it’s difficult to name precisely what they are, and though there are intimations of the figure (could that be a red penis protruding from #165? does #154 remind you of PacMan?), most of the work is resolutely abstract. “People sometimes ask me what a particular sculpture means,” says the artist. “For me, the medium is the message, so the meaning is inherent in the piece.”

Like many members of this site, Blakeslee is a late bloomer, coming into her own about 17 years ago, after years of pursuing other paths. But an interest in the environment and what our culture tosses aside as trash has been with her since she was a child. As a pre-teen, growing up in Baltimore, she cruised the alleys behind neighborhood houses to collect newspapers set out on top of garbage cans. After the papers had piled up in the garage, she and her father took them to a broker downtown who bought them by the pound. From an early age, she developed an entrepreneurial streak. “When I was 12, I started a business called Bristol Household Services—Bristol being my middle name—and turned index cards into business cards to advertise the venture,” she recalls. “I put them around the neighborhood and did errands for people, raking leaves, mowing lawns, going to the store for those who couldn’t get out of the house.”

When it came time for college, she went to Smith, the exclusive women’s school in Northampton, MA. But it wasn’t a good fit. “I came from an integrated high school with 3,000 students in the heart of a city to an isolated place in the wilds of Massachusetts, where I didn’t have a car and had no way to get around.” She quit after two years, moved to Washington, DC, and soon went to work for Common Cause, an organization that fights for an accountable government. Eventually she ended up as executive director for a newly formed study group with the Maryland legislature, which evolved into a writing job with the Institute for Highway Safety (the organization that tests crash dummies). “I knew at that point that if I didn’t return to school to finish my degree, I wouldn’t, so I moved back to Baltimore to study at Johns Hopkins.”

By the late ‘70s, she was in Washington again, primarily as a technical editor, which entails turning complicated jargon, such as economic studies or computer manuals, into lay language. Art was a sometime interest, particularly photography; she took classes at night and built a dark room in a bathroom. But a real love of tactile materials kicked in when she got a job outside the city at what was considered the second-largest fabric store in the country. “I enjoyed walking up and down the aisles and getting acquainted with the fabrics. They offered me a full-time position, but I turned it down because managing a store just wasn’t for me,” she recalls.

Over time she “got tired of hearing that D.C. was the center of the world.” Her sister had been living in Vermont for decades, and on visits to the small towns and rural areas of the Green State, she fell in love with the slower pace and natural surroundings. For four years, after moving to Burlington and then Montpelier, she was executive director of the Vermont Trial Lawyers Association, but a passion for the environment—and for discarded materials—kicked in when she worked for a nonprofit that collected industrial scrap and sold it to the public. “My job was to go around to manufacturers in the state and look in their trash cans,” she says. “I would bring back all kinds of cool stuff—scrap fabric, scrap leather, scrap plastic and metal. Bits and bobs, odds and ends.” Teachers bought the materials to use in the classroom, and Blakeslee began to do what she describes as “crafty things.”

From 1997 to 2001, she created and managed the Center for Sustainable Building. As a sideline, an interest in food and her accomplishments as a chef led her to enter a cooking competition on PBS, one of the earliest reality shows on television. “I went to New York, became the Northeast winner, and then was sent to Hollywood, where I made it as far as the quarter finals.” After that she wrote for online blogs and a respected alternative publication called Seven Days, contributing the first restaurant review for a newspaper in northern Vermont.

Blakeslee has suffered from bouts of lifelong depression, and she is upfront about its impact on her career. “It explains the fits and starts of my work, art and otherwise,” she says. “Art actually suits my situation because I can come and go from it at will, and it is still there when I return.” After launching a website called Eat Vermont.com, which was designed to be consumer-centric but never got off the ground, she turned full-time to sculpture.

All the years of collecting discards have paid off throughout her many ventures, but there have been mishaps, one of the most memorable of which occurred in the mid-‘90s “I learned of a nearby dumpster in Montpelier that was full of cool stuff from an office-supply store,” she recalls. “I always carried a step stool in my truck to get in and out, so I easily made it inside the container. As I gleefully tossed many things out onto the ground several people passed by, half of them smiling, half glaring. But my glee was short-lived because I forgot a cardinal rule of dumpster diving: when you lower the level of the stuff in a dumpster, your exit may not be as easy as your entry. Sure enough, I got stuck. A woman passing by came to my rescue. I forget the actual maneuver, but whatever it was worked. Lesson learned.”

Since 2006, Blakeslee has been living in Bradford, VT, on the eastern border on the state, a conservative place politically but home to a nationally known and respected furniture maker, Copeland Furniture. “I haunt the bins of scrap they put out for the public to take—most burn it but it’s lovely hardwood. I wish I had more woodworking skills so that I could manipulate the wood better, but I can’t resist collecting it. I just got a router which I think will open up many possibilities. I’m still seeking a woodworking mentor to help me with table and band-saw skills.”

She also occasionally goes to metal scrap-yards, and friends bring her random bits of metal and wood they think she might find interesting. “I crowd-source items from the local community,” she adds. “I did this with stringed instruments and with VCR tape, both of which I’ve used as materials.” Wood chunks to use as bases often come from a large timber-frame company. “They offered me a sideways pallet to get into their dumpsters, but that seemed dicey, so I now bring my own ladder. What I can’t use in art I have used to create raised garden beds.”

Blakeslee says she is inspired by the materials she collects but has no preconceived ideas about what she’s going to make. “My overarching goal is to elevate materials into fine art rather than craft and to change the way people view that which they discard.”

Top: #110 (2005), plaster, mung beans, glass bowl, concrete, 12 by 12 inches. Cindy Blakeslee’s studio in Bradford, VT, is on the homepage of Vasari21 for the next couple of weeks.

Hello Ann, I am knocked out by Cindy Blakeslee’S work! As someone who has been working with the somewhat overused term”mixed media”for years; her work really resonates. I just finished a one month residency at SAW-Salem Art Works in Salem NY. where I completed several pieces of sculpture. What a great experience. BTW, I am back in northern NY these days after 17 years in Tennessee. I’d like to send you some pic s of recent work but need to be reminded of the proper criteria to get them on your site. Any help would be appreciated! Talk about late bloomers, I’m still kicking the can down the road at 79…….

Thank you Paul!!