Though they are profoundly simple in composition, Chandrika Marla’s paintings contain an abundance of references. They offer up allusions to the landscape and to the curves of the female body, and they find their antecedents in any number of minimalist and color field artists, beginning with Mark Rothko, the granddaddy of saturated color and pared-down shape, who was an early influence when Marla spotted his works in the Museum of Modern Art in 1999.

Less obvious, particularly to a Western viewer, are the sources for her intense, often jewel-like colors, achieved through layer upon layer of paint applied with an ordinary hardware-store brush roller. Marla was born and raised in New Delhi by a single mother who worked as an interior decorator (her father, a pilot, died when his plane was hijacked in 1977 and the artist was nine). “I grew up in a country where bold color is the norm, and ancient structures and spirituality collide with a shocking lack of respect for women,” she says. “It’s a country of contradictions.”

Marla describes her upbringing as simple, but the family living room was “decorated for client meetings and it was designed to dazzle. A black velvet sofa, red carpeting, oil paintings and antiques, deep accent tables for large speakers. My friends would be drawn to the decadent velvet furnishings, and I had to pull them away and explain the rules each time they visited.” What probably impressed her young eyes the most were the fabrics in her mother’s workspace—“silks, jacquards and velvets, soft and alluring in beautiful deep shades,” as she recalls. “My room had a wall-to-wall cupboard where the extra bolts were stored. I would be reading and one of the cupboards would creak open, and there was my friend, the burgundy velvet, keeping me company.” There were also stacks of books on interior decoration: “It was incredible, the peace I got from seeing those volumes filled with good design and color coordination.”

Her aunt taught her to sew and from the age of 13 she was making her own clothes. “The most exciting aspect of this was hunting for cheap fabric. India is legendary for its intricate weaves and bright silks, and to this date I can go a little crazy when I shop for fabric.”

Her only real art education as a teenager came from a local photographer, and the process impressed her deeply. “Upon entering the dark room, I felt like I was going to school in the night. Photographs hung on something akin to a clothesline, while we manipulated paper in trays. It was like nothing I’d seen before. Each time an image appeared in the tray was a minor miracle for me and I was in control, deciding what to shed light on and what to obscure.”

After earning an undergraduate degree in English literature, Marla decided to study fashion design at the National Institute of Fashion Technology in New Delhi. Her first jobs in the industry entailed working for companies that exported women’s and children’s clothing to Europe. “This involved sourcing fabrics, visiting printings mills, and overseeing the sewing and production of samples,” she recalls. “There was immediacy to the process, and it was gratifying to see my ideas take on a form.”

In 1998, after marrying her high school sweetheart, Sudhakar Marla, she moved to Boston to join her husband while he was doing postdoctoral studies at MIT. The terms of her visa did not permit her to work, so she took classes in pottery, as well as Adobe Illustrator and Photoshop (two processes she still uses in plotting out her canvases). “This was the first time in my life that I had to deal with loneliness and figure out ways to stay occupied on a very tight budget.”

In 2000, the couple moved to Chicago, where Marla worked as a designer for companies in India and New York and gave birth to her son in 2005. A year later, laid off from a job designing children’s clothing, she joined a painting class at a local art center, the North Shore Art League. “I can’t say that I had a burning passion to paint, but I did know that I needed to do something creative,” she says. “My teacher told me months later how sincere—and probably absurd—I was on the first day of class. I described the Rothkos I remembered and suggested that he teach me how to paint like that, while waving my arms around, recalling the immense swaths of transcendent color.”

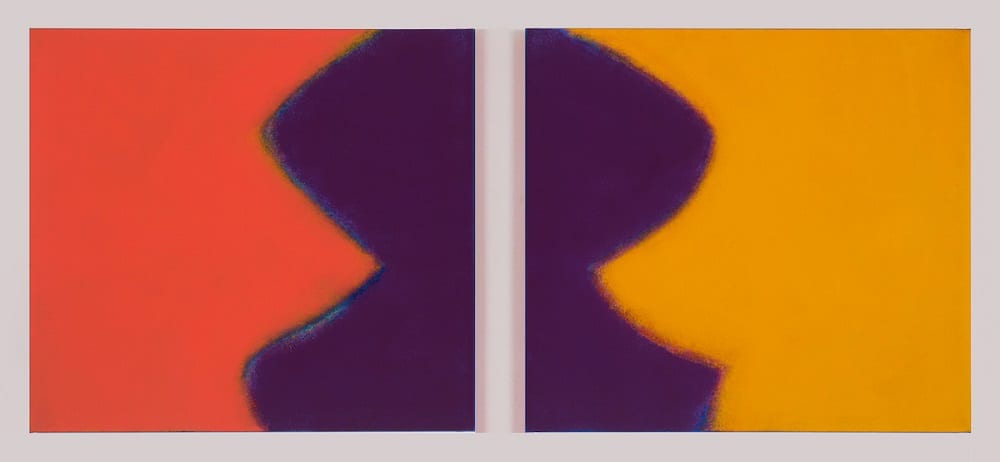

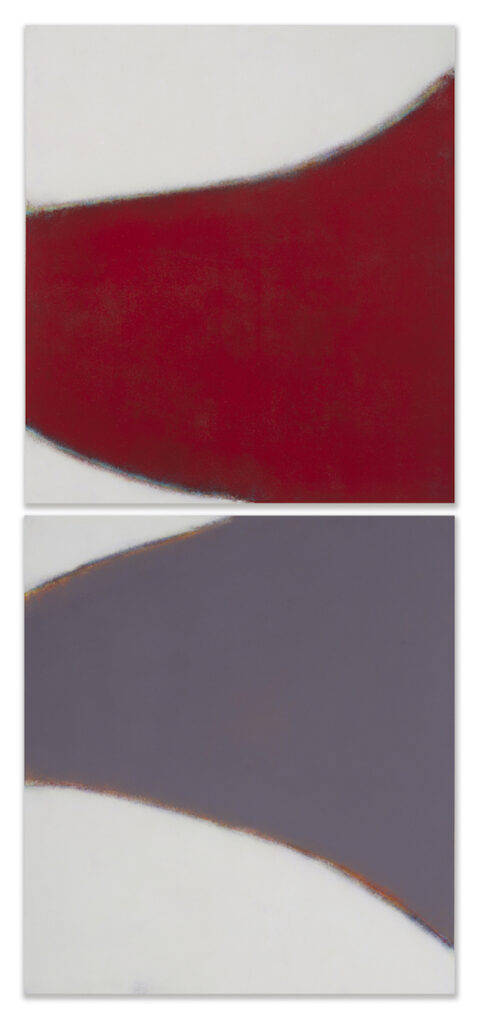

After a couple of “failed Rothko attempts,” she began painting anthropomorphic shapes with heads and shoulders. The paintings had a reversible quality to them. “If you hung them upside down, you would get the same image. I called this first series ‘Inversions.’ But within a year I dispensed with the heads and started making these beautiful shapes of seated figures, still headless.”

During her time in Chicago, a few experiences helped reinforce her path toward becoming an artist. At a high school reunion in New Delhi, she met a friend she hadn’t seen in decades, a well-known Bharatanatyam dancer trained in the oldest classical dance tradition in India. “I decided to organize a program for her to dance in Chicago. At some point she decided that she wanted to dance to my paintings, and this suggestion shocked me, that someone of her expertise could interpret my work.

“At the performance, which was absolutely exquisite, she told the audience that she wanted to dance to my paintings because my protagonists had no limbs and she wanted to make them fly. This was one of the most beautiful experiences of my life, seeing my forms come alive through her movements.”

Marla also joined a critique group headed by Sarah Krepp, and for four years, once a month, met with other artists, a transformative involvement because she had never before been exposed to serious artists. She also had her first solo show at the Mars Gallery.

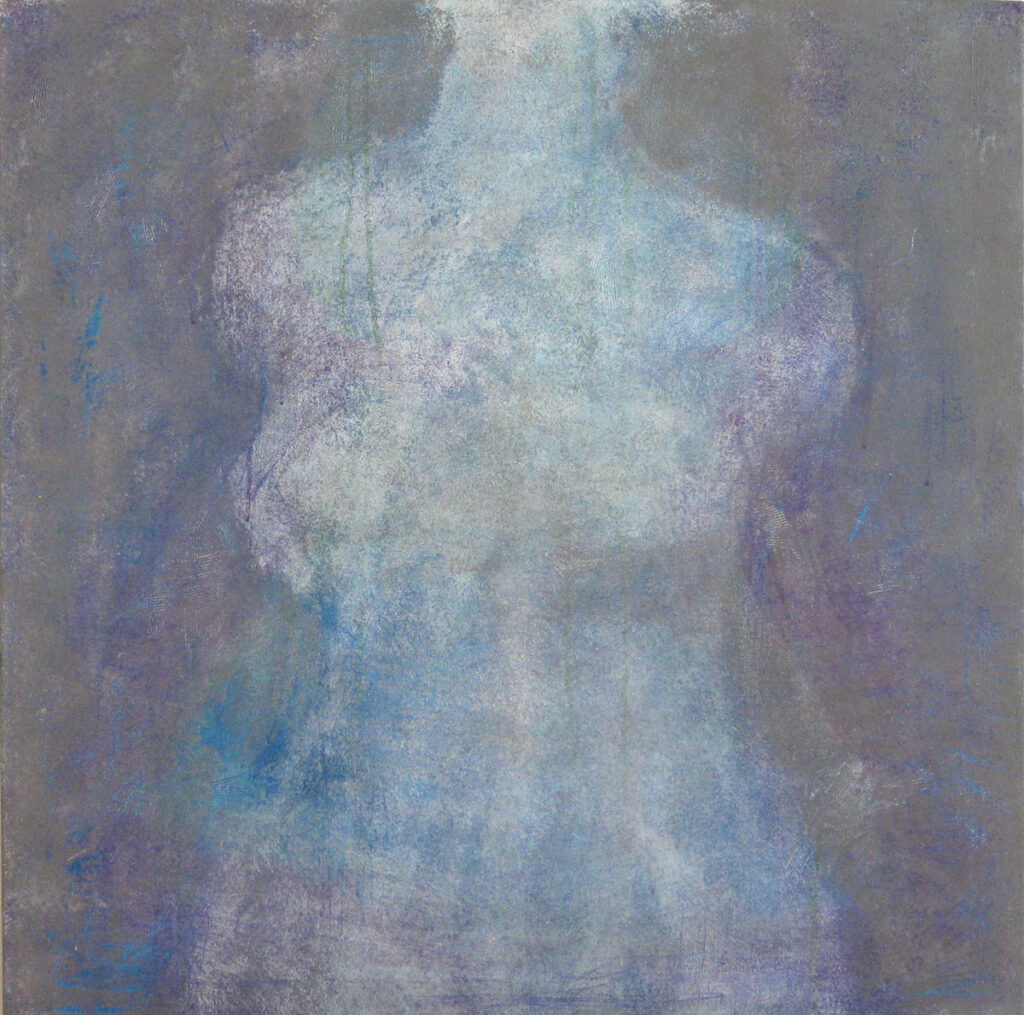

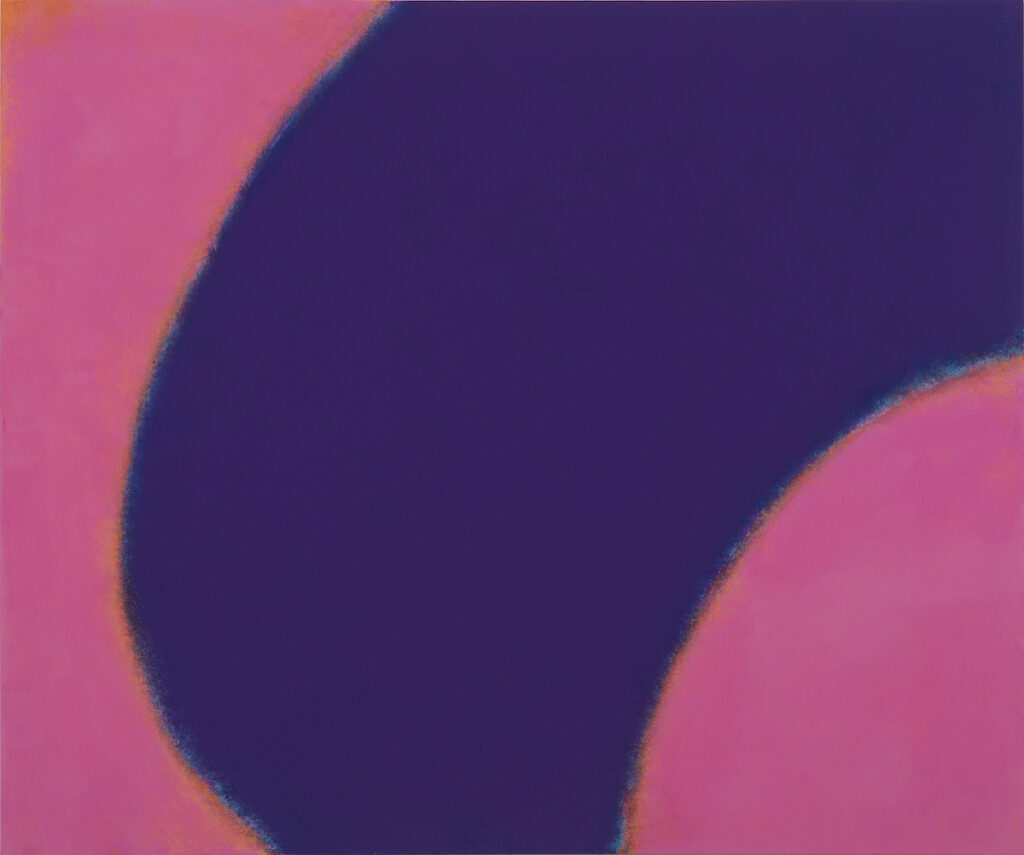

“Unfortunately, with the solo show and the dance performance within a few months of each other, I think I had taken on too much too soon.” She started have panic attacks, and was soon battling claustrophobia as well. “When I went to my studio, I couldn’t deal with intense color. This is when I made a series of white figures on pastel backgrounds and began to use a roller. But after a year of these ghostlike white figures, my original love of color came back, and I started zooming into the torso and creating simplified shapes based on female breasts and shoulders.”

In 2017, Marla and her family moved to Mountain View, CA, for her “mental health and his career.” She is now an artist-in-residence at Cubberley Studios, a competitive program run by the city of Palo Alto. In her work, she continues to explore the feminine in simple shapes composed of between seven and twenty layers of acrylic, divided by a stippled line. “The vivid colors are in the background of all my childhood memories,” she says, “and I am still trying to grasp what the line divides.”

Top: And Then They Were Two (2019), acrylic on canvas, diptych, each 35 by 35 inches

What an inspiring interview!

Thanks, Payal. I hope you’ll visit the Bay Area soon and experience the work in person.

This is such a fascinating story of this artist’s journey. Her story, along with the rich layers of color and history in the images, is a vivid testament to what inspires this maker to create.

Thank you, Susan! I’m so glad that you enjoyed reading about my artistic journey.

Chandrika, such beautiful, mesmerizing work and story!!

I’m glad you got to see some of my earlier work, Karen!