Timehri No. 1 (1968), string, oil paints on Masonite board, 36 by 48 inches (photograph courtesy of Ohene Koama)

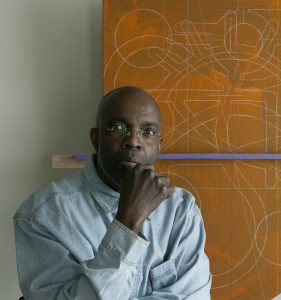

Though it may not be immediately apparent in his elegant abstractions in many different mediums, Andrew Lyght’s works are infused with memories of his boyhood in Guyana, a small multicultural country on South America’s northern coast. The only child of a single mother who struggled to make a living as a seamstress, he remembers the ways in which she took clothes apart and put them back together. “The construction and deconstruction of the picture plane came from looking at my mom’s work,” he says. When color entered his imagery in a serious way in the 1970s, he recalled the hues of garments flapping on the small household’s clothesline.

For pocket money, the artist made and sold kites to neighborhood kids, and kite-like forms recur in many of his mature constructions. “I looked closely at all of the different things going on around me,” he told curator Artemis Zenetou. “I was encouraged to try my hand at building and painting houses, to paint billboards and to help out with the bending and clamping of wood in a boat yard after school and on weekends.” All these skills would come into play when he worked in construction and developed his vocabulary as an artist.

Painting Structures (1985), Atrium IV, S/A Associates, Somerset, New Jersey, Bamboo, matte varnish, nylon cords, and acrylic on canvas, 20 by 65 by 25 feet (photograph courtesy of Malcolm Varon)

At the age of eight, he started drawing and dabbling in watercolor. When he won a competition in school, he came to the attention of the country’s leading artist, Edward R. Burrowes, and was soon working almost full-time as his apprentice. Burrowes had studied in Europe, and his demanding curriculum emulated Renaissance training methods so that the teenager first learned to handle materials and then proceeded to draw, paint, and sculpt. Because Lyght suffered from a stutter, his teacher particularly emphasized drawing, believing the meditative state induced would help with his breathing and speaking.

By the time he was 20, Lyght had won numerous competitions and trophies and was gradually moving away from figurative work to more experimental forms. He studied Timehri rock paintings and drawings found in the interior of Guyana, and the fluid curving shapes of the Amerindian tribe still find an echo in his mature drawings.

His world changed dramatically when he won a scholarship to study at the Saidye Bronfman Centre in Montreal. It wasn’t a matter of abandoning Guyana, he says. It was simply time to go. He also realized he needed the proximity to New York to absorb the latest currents in contemporary art (among the few books he carried with him was the catalogue for the Museum of Modern Art’s Landmark show “Sixteen Americans”—a group that included Jasper Johns, Ellsworth Kelly, Alfred Leslie, Louise Nevelson, Robert Rauschenberg, and Frank Stella).

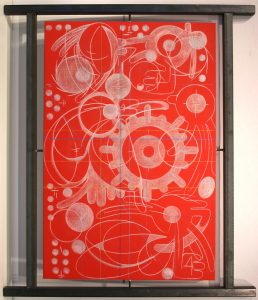

Industrial Painting/Sheathing 0340RD (1998-01), Rust-oleum enamel, Prismacolor pencil on steel sheathing, post-and-lintel steel frame, 44 by 51 inches (image courtesy of the artist)

His initiation into a new and urban environment in a chilly northern climate was a challenging one (this was the first time he ever had a telephone), so much so that the artist stopped painting for year. He worked in a cafeteria and spent his spare time looking and drawing. “I was experiencing the different seasons, fall, the changing colors, the leaves on the ground, tree skeletons, seeing snow for first time.” But his ties with his home country remained strong. Lyght was selected to represent Guyana in the XI Biennale in Sao Paulo and returned to Georgetown to be the guest of the government at the first Caribbean Festival of the Creative Arts in 1972. Two years later, at the age of 25, he had his first solo show at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.

In-Flight 0033 (2005), installation at the American Academy in Rome, Italy; nylon cords, acrylic paint, Prismacolor pencil on plywood sheathing, 36 by 144 by 84 inches (photograph courtesy of Gary Dwyer)

By 1977, Lyght decided it was time to move to New York. He put all his large paintings, art books, and equipment in storage and hopped a bus to Port Authority. “I had two pairs of jeans, two shirts, $150 in my pocket, and a single artwork that folded into a portable case,” he recalls. Through friends, he met the filmmaker and art impresario Emile de Antonio, who was impressed with the artist and his work, and in turn introduced him to critic Barbara Rose, another early supporter. Rose helped him find a job and studio space at P.S. 1, then a fledgling cutting-edge art space in Queens, where he could camp out in a sleeping bag at night. Through De Antonio, he also met Andy Warhol (who advised him to drop the “Andrew” and go by the name “Lyght”), Frank Stella, Leo Castelli, and other dealers.

Drawing Structures G741 (2016), red oak, paint stick, acrylic paint, prisms color pencil on plywood, steel bolts, 45 x 45 x 9.1/2 inches.

After his two-year residency at P.S. 1, the artist moved to Williamsburg in Brooklyn, where he worked at construction, continued to make art, and soon became caught up in the kind of real-estate hell common to communities on the brink of gentrification. In 2004, after renovating through large spaces in exchange for free rent, Lyght lost a six-year court battle for his third and final loft in Williamsburg. But as luck would have it, at the point when he was the last person living in the building, he landed a grant for $150,000 from the Barnett and Annalea Newman Foundation. He took ten months to pack up and then went to Europe for a year, a sojourn that included a three-month artist residency at the American Academy in Rome and six months in Tuscany. “While I created a series of wall pieces at the American Academy in Rome I also began setting up a virtual studio on my laptop computer,” he told Zenetou. “I taught myself how to use digital technology, learning Photoshop and CAD software. Upon returning to the United States, I began transforming and reinventing my studio practice, integrating photography with CAD technology and drawing into a new series of hybrid works on paper.”

Painting Structures 645C (2017), red oak, paint stick, acrylic paint, Prismacolor pencil on plywood, 42.5 by 38 by 5 inches (image courtesy of the artist)

Back in the U.S., after a period of makeshift living situations, including a year of couch-surfing with friends, Lyght won another grant, this time from the Adolph Gottlieb Foundation, and in 2010 he purchased a 19th-century brick barn in Kingston, NY. “I began renovating my new studio/home, ‘Lyght Box,’ stripping the building back to its bare brick shell, leaving intact only the original chestnut floor on the second level hayloft,” he recalls. “While making architectural drawings for the interior space of my new home and filing for a building permit I was reminded of the type of stick-frame house construction that I had grown up with in Guyana.”

The last eight years have been good ones for the artist, whose handsomely renovated mule barn received the Annual Preservation Award from the Friends of Historic Kingston in 2012 “in deep appreciation for preserving our architectural and cultural heritage.” In 2016, he landed a smart retrospective at the Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art at the State University of New York at New Paltz, an exhibition that earned high praise from The New York Times. The reviewer called it a “stunning show” and noted that his work “blurs all distinctions between drawing, painting, sculpture, digital photography and installation art.” He has been featured in Sculpture magazine, and this spring he will have a solo show at the esteemed Skoto Gallery in Chelsea.

It has been a long, winding, and often arduous journey from Guyana to upstate New York, but Lyght shrugs off the difficulties. Modestly, he credits much of his grit and determination to his mother. “My whole attitude came from my mom,” he says. “We didn’t have much, but I never saw myself as a victim. She thought the sky was the limit.”

Ann Landi

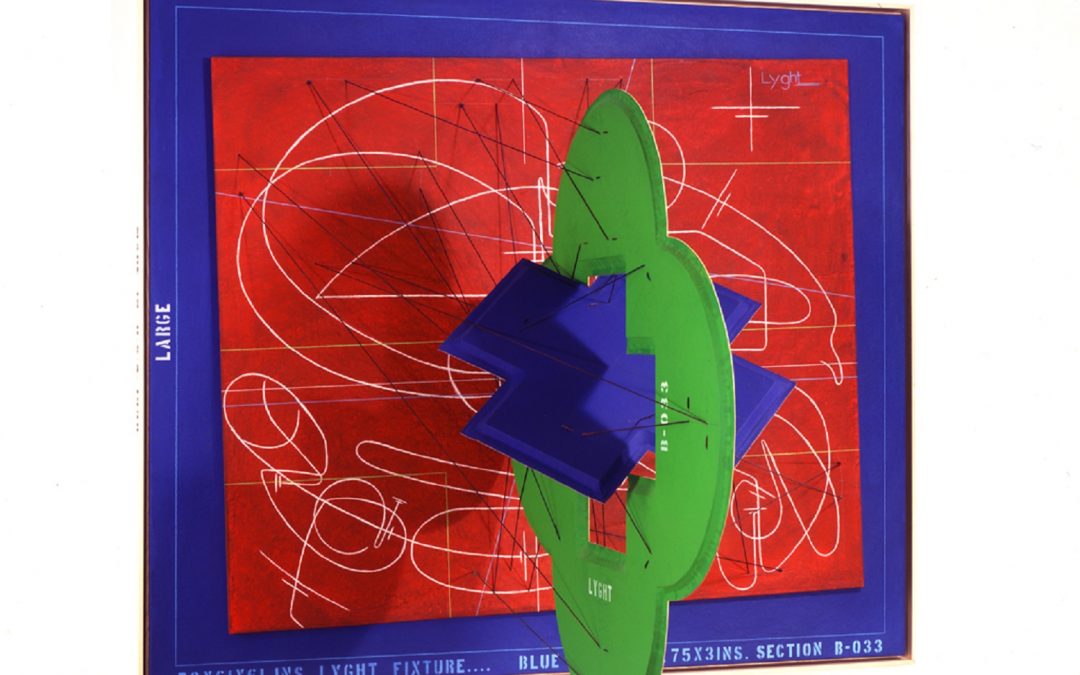

Top: LyghtFixture/Blue Section, B-033 (1990), Prismacolor pencil, nylon cords, acrylic on canvas, plywood, 60 by 84 by 72 inches

I love this work and great article.

LOVE his work. Thank you!

LOVE his work. Thank you!

I’m still a little mystified by hashtagging too! If anyone has additional advice please do post it here.

What a nice tribute to a unique artist! I remember Andrew Lyght from PS 1, and I enjoyed reading about the underpinnings of his work.

Fantastic work. Thank you Ann for this wonderful piece about him. Very inspiring!

Congratulations, Andrew! A wonderful and well deserved article.

Wow! This guy got all the right breaks….”Through friends, he met the filmmaker and art impresario Emile de Antonio, who was impressed with the artist and his work, and in turn introduced him to critic Barbara Rose, another early supporter. Rose helped him find a job and studio space at P.S. 1, then a fledgling cutting-edge art space in Queens, where he could camp out in a sleeping bag at night. Through De Antonio, he also met Andy Warhol (who advised him to drop the “Andrew” and go by the name “Lyght”), Frank Stella, Leo Castelli, and other dealers.”

I wonder if the work of very good artists, such as Lyght, gets even better because of the good fortune such acquaintances can provide. And then….his good instinct to keep moving north toward the art mecca – NYC. A good read. Thanks.

Lovely article and portrait of a beautiful person. I know how hard he has worked and has developed an intriguing and consistent style in his art throughout the years. Congratulations Mr. Lyght. Recognition well deserved!