Why set oneself the task of watching all the movies about Vincent van Gogh available for streaming during this period of lockdown and self-isolation? I believe the initial suggestion came from Amazon Prime, way back in February, when the site proposed Robert Altman’s “Vincent and Theo” and I realized I’d never seen it, nor did I remember catching the granddaddy of all van Gogh biopics, Vincente Minnelli’s “Lust for Life,” starring mid-century superstars Kirk Douglas and Anthony Quinn.

Why there seem to be no films about van Gogh prior to 1956 is somewhat of a mystery. Irving Stone’s bestseller, which inspired the Minnelli movie of the same name, was published in 1934. So the high drama that infused the paintings and made tales of the artist’s life so irresistible had been in general circulation for two decades, and even the deeply affecting correspondence between Vincent and his brother, Theo, though probably not of much interest to a mass-market audience, has been around since 1914.

Nonetheless, the bulk of Vincent movies—about eight to be found online—dates from 1990. Perhaps it was the record $39.9 million paid for Sunflowers at auction in 1987 that jump-started interest. Or perhaps contemporary filmmakers feel more resonance with the details of the artist’s life or see the potential for bravura cinematography in the paintings themselves. And what a life (and death)! Van Gogh worked for a while as a minister among coal miners, set up housekeeping with a prostitute, met some of the artistic giants of his day in Paris, decamped to the south of France to realize most of his greatest works, and committed suicide in a cornfield in July of 1890 (though the 2012 biography by Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith suggests he was murdered by a local teenager). And then of course there was the madness, the nine turbulent weeks with Gauguin in Arles, the year-long stay in the asylum at St. Remy And that ear.

Minnelli’s two-hour extravaganza, starring Kirk Douglas as Vincent and Anthony Quinn as Gauguin (the latter won an Oscar for best supporting actor) covers the artist’s adult life from his time among the coal miners through his death in the cornfield, adhering to the known facts without descending into bathos. It’s a big lush production with a heaving musical score and panoramic shots of European landscapes. The costumes, of course, look dated and the dialogue seems often stagey and stilted, but Douglas acquits himself admirably as the neurotic Vincent and there are two indelible scenes: the artist painting by candles affixed to his straw hat and the attack of crows among the cornstalks. Maybe a period piece, but still riveting.

The sale of “Irises” for $53.9 million may have kicked off a wave of interest among filmmakers in 1987

If my research is correct, the next van Gogh production is not until more than 30 years later, when Robert Altman tackles the tale with “Vincent and Theo,” a kind of double portrait of the brothers as equally unhinged but inhabiting different worlds. Theo is the smooth operator in the Parisian gallery business while Vincent rages his way, occasionally munching on paint, to his mature style. I rented the four-hour mini-series on Amazon Prime, and couldn’t make it halfway through the third installment. Some of Altman’s trademarks—overlapping dialogue, aggressive zooming camerawork—are here, but I found the whole thing a tedious slog.

A far gentler and more modest approach to the bond between the brothers is explored in “Vincent van Gogh: Painted with Words,” with Benedict Cumberbatch as the artist in a movie released in 2010, the same year his fame really took off in the BBC production of “Sherlock.” This is perhaps the most art historically satisfying of the biopics, concentrating on van Gogh’s development from a clumsy sketcher of rural life to the sublime draftsman and colorist of the last years. There’s even a bit of serious discussion about his passion for Japanese prints, and in dialogue drawn entirely from the letters, van Gogh emerges as much less of a nutter and more the serious, questing genius we see on museum walls.

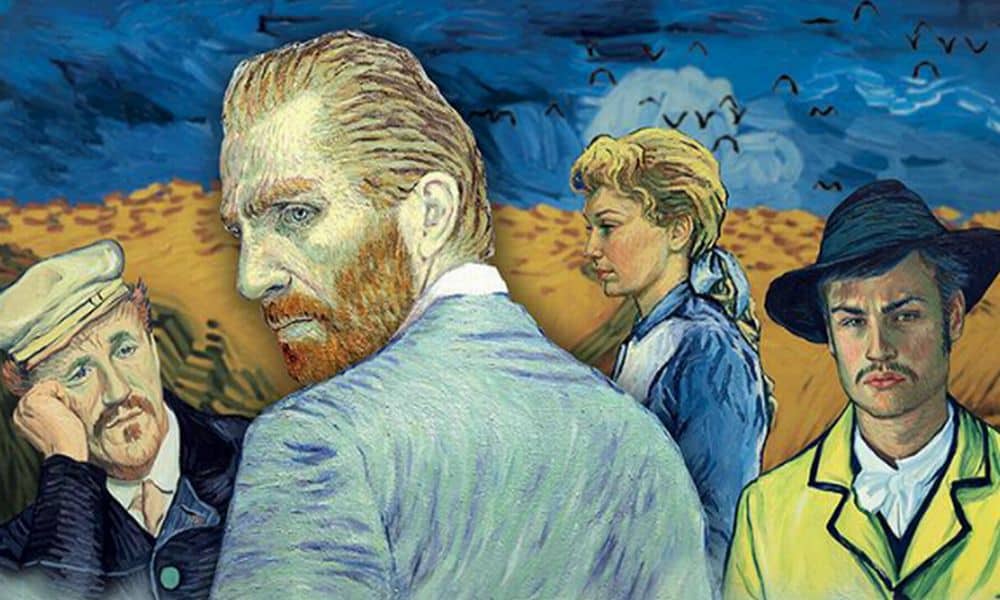

“Loving Vincent” and “At Eternity’s Gate,” from 2017 and 2018, demonstrate the polar extremes the van Gogh story can inspire. The former, directed by Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman, uses tens of thousands of oil paintings commissioned from scores of artists, to tell the story of Vincent’s last days in a sort of hypnotic and protracted cartoon. The characters van Gogh depicted on canvas—the postman Roulin, Dr. Gachet, the innkeepers and barmaids, farmers and townsfolk—are brought to life, abetted by professional actors like Saorse Ronin and Chris O’Dowd. It’s a kind of meandering detective story narrated by the postman’s son, Armand Roulin, that never really grips the viewer once the novelty of the visuals wears off, and it’s far more effective on the big screen, where I first saw it, than on a laptop or home television.

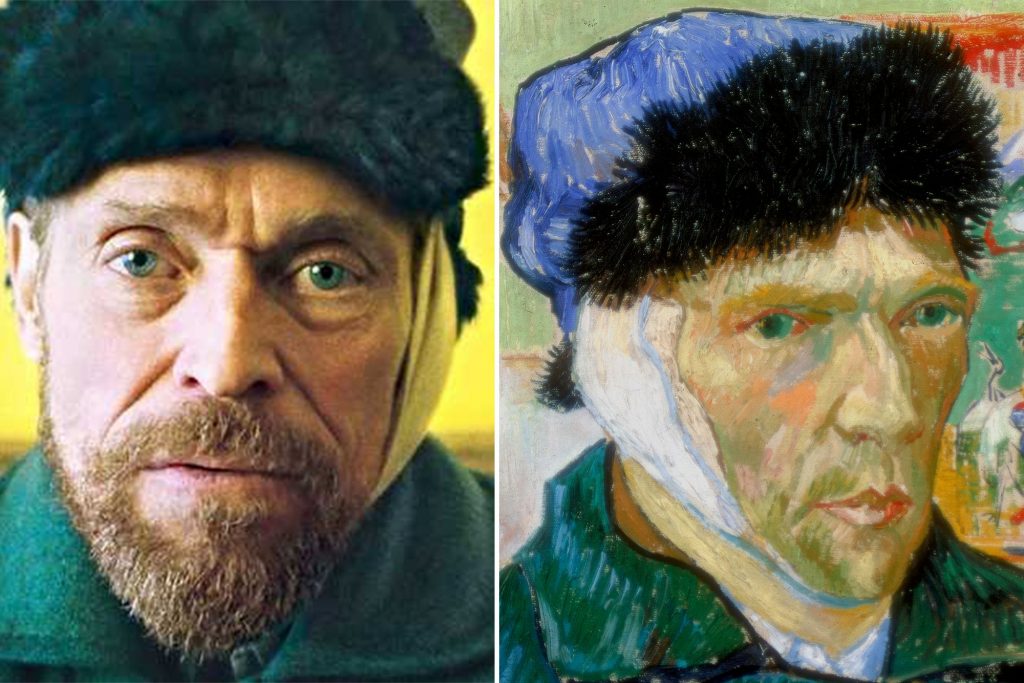

Though more than two decades older than the tormented painter when he died at 37, Dafoe offered a bravura performance as Vincent

Julian Schnabel’s “At Eternity’s Gate” is perhaps the most intense and painterly exploration of Vincent’s last days. Not too surprising from an artist who has turned to movie-making with exquisite skill in films like “Basquiat” and “The Diving Bell and the Butterfly.” Willem Dafoe, in his 60s, effectively captures both the tenderness and the ferocity of the 37-year-old painter, but the wobbly handheld camera technique, the interminable tromping over hill and dale in Provence, and a couple of risible and talky scenes—one in a therapeutic bath in the asylum, another with a sympathetic priest, discussing God, painting, and Nature—seriously try the viewer’s patience. I was screaming for a glass of absinthe long before the final frame.

The unexpected sleeper hit in this barrage of van Gogh filmography (and there are a few I’ve left out owing to the reviewer’s exhaustion with the subject) is not really a film at all. It’s a one-man performance called “Vincent” by Leonard Nimoy from 2006, available on Amazon Prime, recorded at the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis. Drawing on the more than 500 letters, Nimoy plays both Theo and Vincent in the days after the funeral, as slides of the artist’s work are projected in the background. He makes vivid van Gogh’s surliness, his demands on others, and the ways in which he was tormented by the Arlesiennes in his final days, who “pursued him like a hunted animal.” The bond between the brothers is breathtakingly dramatized, with Nimoy slipping easily between the two characters. In all the tributes to filial love, this is easily the most moving. I was in tears at the end.

So if you dip into only one of the van Gogh stories available for streaming, go for Nimoy’s “Vincent.” The others cover the territory in intriguing ways, but this one rips out your heart.

Top: The hand-painted cast of characters from “Loving Vincent”