There are many artists who might be said to channel the impulses of childhood into their mature works—Picasso, Klee, and Dubuffet are three who come to mind. But few I know of carry over a talisman from their earlier years as an important subject in their so-called mature works.

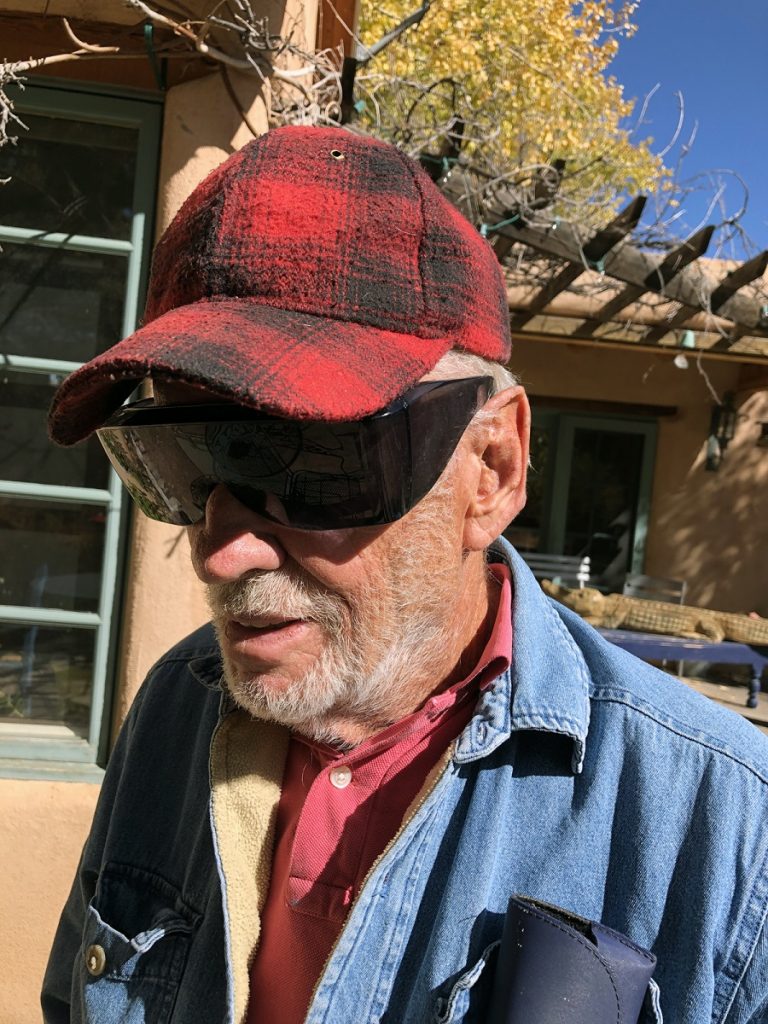

When he was a very small child, Ira Wright, who is now 87, remembers going to the movies to see Mickey Mouse cartoons at the theater in his hometown of Kalamazoo, MI. “He was huge, of course, on the screen,” he remembers. “And this was like magic.”

Not long after that he was given a toy made from rubber and shaped like Mickey. The arm broke off; the mouse could not be fixed, because there is no way you can easily repair rubber, and Mickey ended up in the trash. But Ira, then three or four years old, couldn’t stop thinking about the toy and first thing the next morning went to retrieve him from the waste bin. Alas, by then the trash man had come and gone, and Wright was devastated.

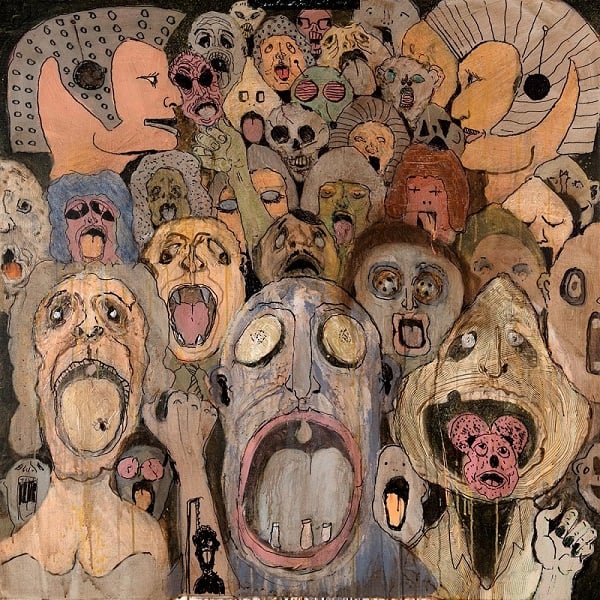

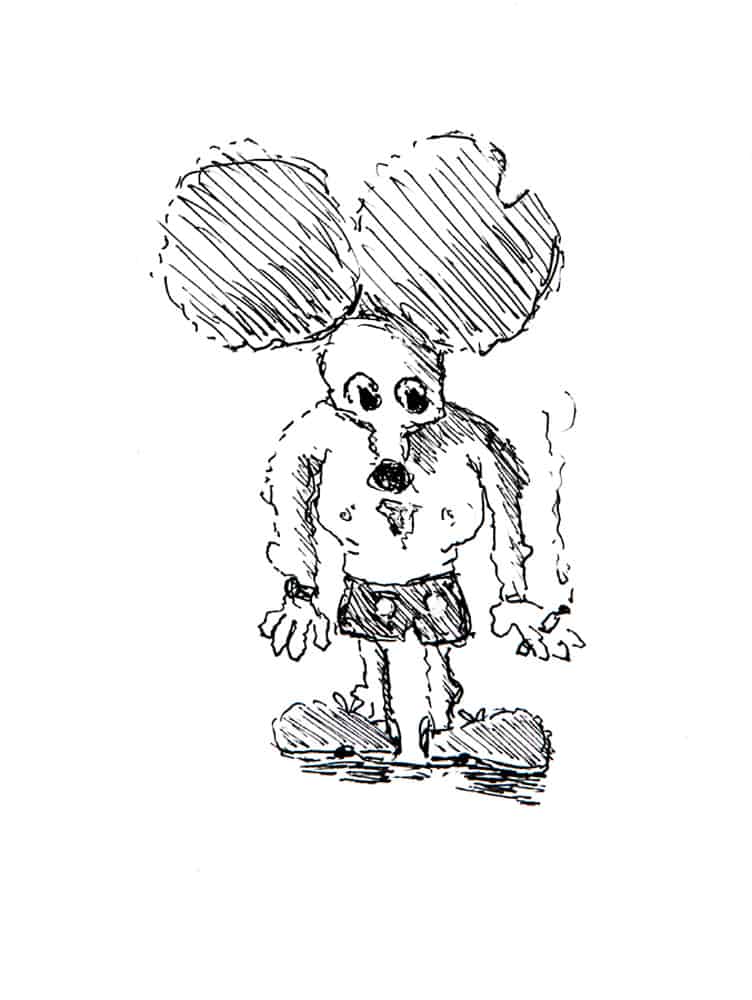

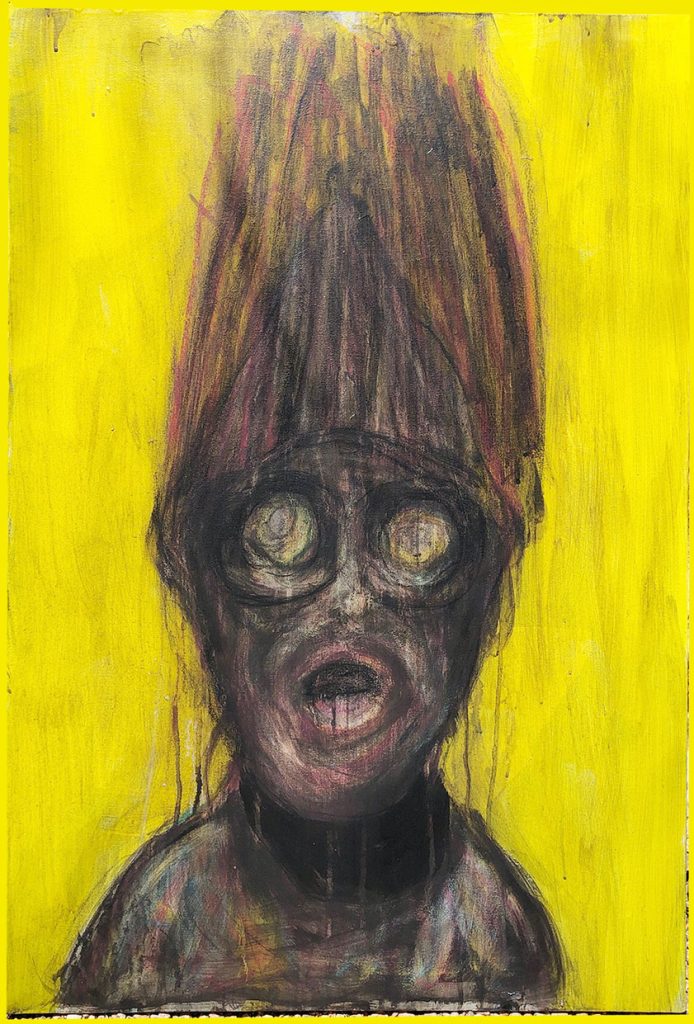

Mickey turns up now, more than eight decades later, mostly in his drawings, but also in group scenes like Rally (2018), where he is trapped inside one of the mouths of a screaming crowd, who seem to be watched over by two Roman centurions. But he more commonly appears in the artist’s drawings in many different humors: Mickey can be a benign figure in a coat and tie or a monstrous apparition smoking a cigarette or leering at the viewer under tattered ears.

Wright says he is both “a golem and a companion.”

As a child, Wright got little encouragement from his parents to give full rein to his artistic impulses (attempts to tamper with the iconography of the wallpaper met with severe disapproval), though an aunt who came over from Paris during the war “made a huge impression” because of the landscapes she painted and the box of pastel she gave the boy as a gift.

When it came time to head off to college, at the University of Michigan, Wright settled on a major in industrial design because it was a subject his father, a banker, would approve. He continued to study design at Cranbrook, where groundbreaking designers Charles and Ray Eames were on the faculty, along with Morris Brose, a Polish-born sculptor whose works in bronze show a prickly modernist sensibility. “The Eameses represented a new aesthetics that opened my mind to the notion that art could be practiced in many ways, practical as well as esoteric,” he says. “And Morris Brose showed me the kind of commitment a life in art required.”

Because his father had a connection with Litton Industries, which was still in its infancy but would later become one of the largest conglomerates in the world, Wright moved to Orange, NJ. He designed the cases for early computers, which were then about the size of a desk, and had the distinction of naming a custom color “Tahitian Sunrise.” After a few years, he returned to Kalamazoo and worked at a succession of jobs—including gigs as an art director and graphic designer at an ad agency, a foundry worker, and a teacher of studio art and art history at local colleges.

Though he wasn’t seriously pursuing art as either career or avocation, he did end up running a gallery “for artists who couldn’t get shows anywhere.” It was called Six17 and was “hugely popular but not financially successful.” By then Wright had three kids, and his daughter helped write press releases and catalogues. “The evening openings got out of control and we had to quit serving booze,” he recalls

As a single father, the artist often took trips with his kids when they were teenagers. When the family wanted to go somewhere out west, they ended up in Santa Fe, NM. “And I said, that’s where I’m going to move,” he recalls. “The light, the landscape, the tranquility. There was a peacefulness that didn’t exist in places where I’d lived before.”

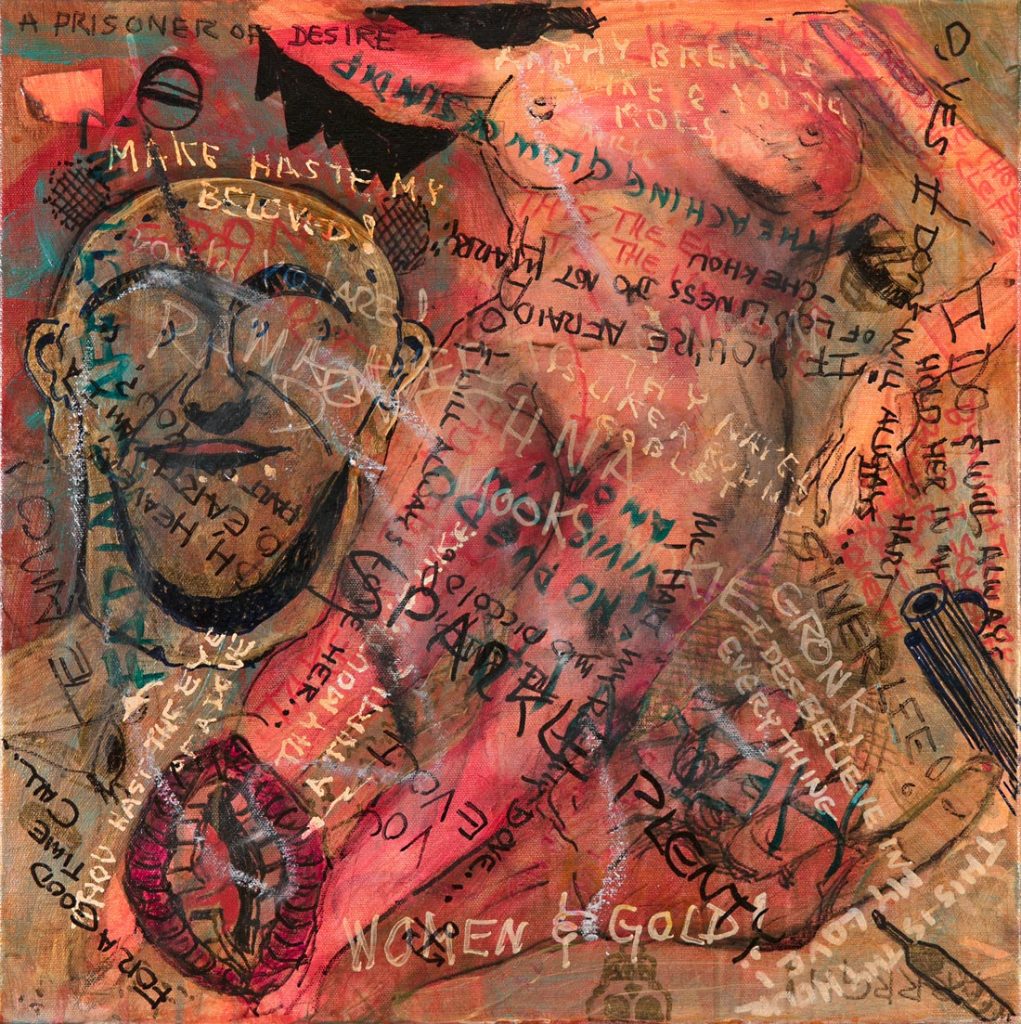

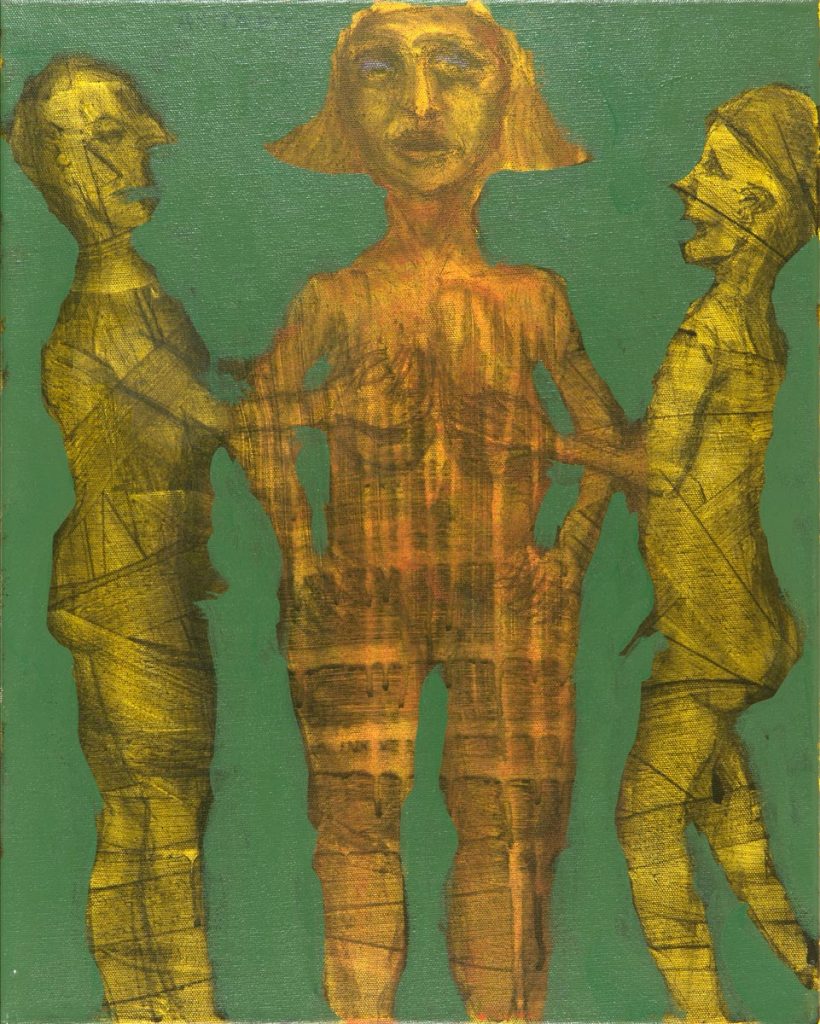

Since 2004, Wright has lived in a sun-drenched house and studio just north of Santa Fe. His surroundings may be tranquil, but what emerges from his imagination is far from peaceable. His larger tableaux include bare-breasted women, skulls, disembodied hands, slobbering dogs, exotic masks, and guys who can’t seem to keep their mitts off the nude and semi-nude female figures. His is an aesthetic as bitingly crazed as Ralph Steadman’s, who made his name illustrating Hunter Thompson’s zany reportage. Words and sentences sometimes march across the surfaces—“sparkle plenty,” “women in gold,” “for a good time call”—but one is reluctant to scrape too hard for literal interpretations. He will say that Susan Sontag appears in a party scene because he likes “brilliant, somewhat wacky Jewish women,” but beyond that he doesn’t elaborate.

And when so much of the imagery has the feel of a waking nightmare or a bad acid trip, it may be best not to inquire too closely. We live in a period that defies easy explanations, when the barbarians are always at the gate. There’s no good reason to expect art to reflect an ordered and sensible universe when we’re all overwhelmed by mayhem and fear. Wright fits in neatly with the temper of the times.

More about Ira Wright can be found on Instagram @theartofwright and his website.

Top: Rally (2018), mixed media on canvas, 28 by 28 inches

Terrific job Ann. This guy really needs to make art, and to be so productive at 87 is astonishing.

I love this article and Wright’s work!

These are raw and unnerving pieces with the power of outsider art. I hope I’m making art at 87, and I hope it’s this arresting.

I don’t know you Ira, but wish I did. Your work really appeals to me. What also appeals to me is that you are a man of few words and you let your images speak for themselves. As it should be as far as I’m concerned.