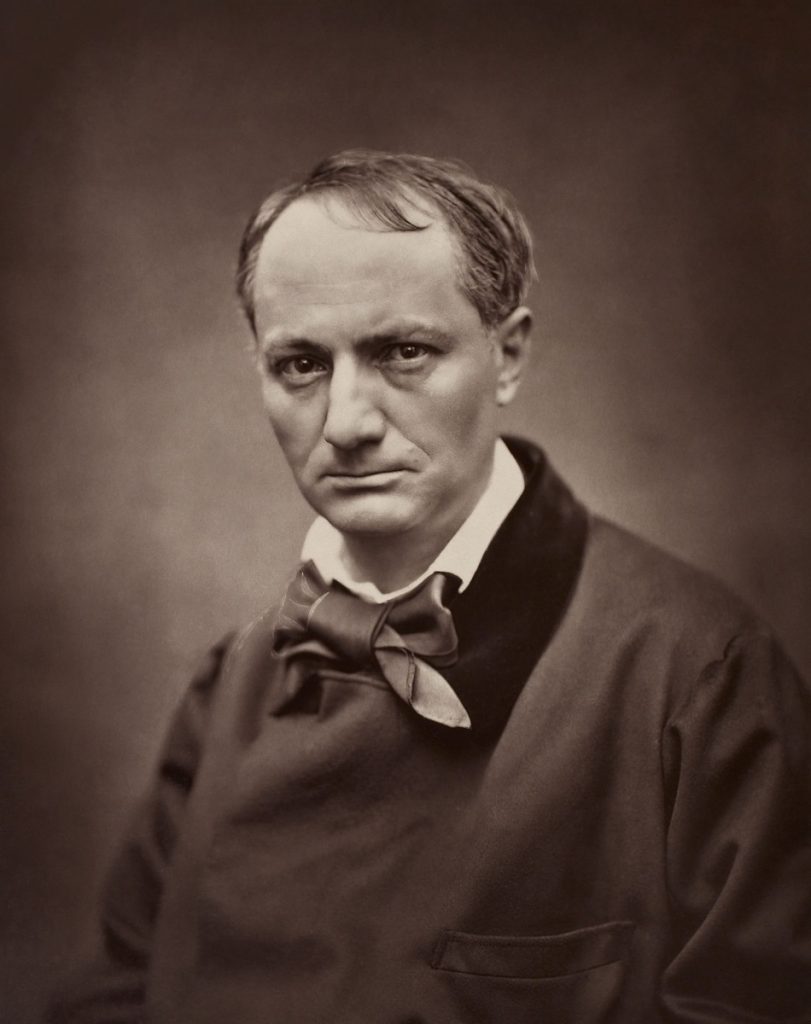

Who Was the Mysterious Mistress Immortalized by Two 19th-century Geniuses, Charles Baudelaire and Édouard Manet

The widespread protests in the wake of George Floyd’s murder in May, abetted by the swelling powers of the Black Lives Matter movement, got some of us with an interest in art history thinking about the accomplishments of many underknown Black artists (not the usual suspects like Kara Walker, Nari Ward, and Nick Cave). And so I started posting (and will continue to post) on social media about noteworthy artists who never spent much time in the limelight, including Benny Andrews, Mary Lee Bendolph, Bill Traylor, Barbara Chase-Riboud, and others.

But Black artists are not the only aspect of art history, past and present, to fly under the radar. For centuries, Black models have served to supply the ends of mostly white artists, from Velázquez to Eakins to Matisse, playing important roles in mammoth tableaux like Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa and John Singleton Copley’s Watson and the Shark.

Women of color were critical to (mostly male) artistic visions as well, figuring importantly in such milestones of art history as Manet’s Olympia and Matisse’s “Jazz” sketches and cutouts. (This territory was thrillingly surveyed in one of those shows I deeply regret missing: “Posing Modernity: The Black Model From Manet and Matisse to Today,” a traveling exhibition that debuted at the Wallach Gallery in New York in late 2018).

John Singleton Copley, Watson and the Shark (1782), oil on canvas, 36 by 30 inches, Detroit Institute of the Arts

But of all the Black models in Western art, the one who has most intrigued me is Jeanne Duval, mistress of Charles Baudelaire, immortalized in Manet’s portrait of 1862, roughly a year after the poet and painter became fast friends, and also a year after Baudelaire broke off the stormy 20-year liaison with his dark-skinned muse, who by then had suffered a stroke and was nearly blind.

One of the reasons I’ve always been seduced by Manet is because so many of his paintings pose baffling mysteries about their ultimate meaning: he has teased art historians for decades in works like The Bar at the Folies Bergère, Le Déjeuner sur L’Herbe, and the scandalous Olympia, consigned to a dark corner when it was shown at the Salon in 1865.

The portrait of Duval is no exception, and is perplexing not just in its subject but in its execution and composition. The hand of the somewhat haggard-looking model is larger than her head; one foot protrudes at an angle that makes it impossible to imagine it joined to the hip; and nearly half the painting is dominated by Duval’s loosely painted voluminous dress, identified as a crinoline popular among the fashionable set of the 1860s.”One can assume that Manet intended Baudelaire to be the prime viewer of the portrait and planned to give it to him, perhaps in gratitude for the favorable notice the poet gave him for his essay ‘L’eau forte est a la mode,’ which appeared in 1862 in ‘La Revue Anecdotique,’” wrote art historian Therese Dolan in The Art Bulletin in 1997.

But back to that model. Securely identified as the inspiration behind Baudelaire’s cycle of poems Les Fleurs du Mal, Duval is celebrated in verses of an extreme sensuality abhorrent to many readers in mid-19th-century Paris

“My loved one was naked and, knowing my heart/Was dressed only in the music of her jewelry”

“So she lay upon a divan preparing to be loved,/Smiling on my lust, as it rose like the tide of a distant sea”

“Her legs, her arms, her thighs, polished as if with oil,/Uncoiled with swanlike grace before my eyes;/Her belly, loins and breasts, the fruit of my vine,/Thrust themselves forward, more tempting than demi-angels….”

And so it goes in a few of the choicer verses from “Les Bijoux.” Not exactly as lewd as most present-day pornography, or even John Updike, but nasty enough to bring Baudelaire and his volume to trial. Ultimately six poems had to be excluded from the cycle; its publisher nearly went bankrupt; and Baudelaire failed to achieve the financial and critical acclaim he was sure Les Fleurs du Mal would bring his way.

But not all that heat and passion was confined to the bedroom. The long Baudelaire-Duval relationship was one we would today characterize as co-dependent to an extreme. “Baudelaire claimed that Duval made him suffer greatly, admitted striking her on the head with a console table, and more than once he sold her jewels and furniture,” reports Dolan. “When they were apart, however, he grieved intensely. She was his single distraction, his sole pleasure, his only friend, and the sight of a beautiful object or lovely landscape made him long for the pleasure of sharing his thoughts with her.”

About Duval herself, though, little appears to be certain. She is described as a “quarteroon”—three-quarters white, one-quarter Black—but her birthplace in varying accounts is cited as Nantes, Guadeloupe, Martinique, or Haiti. “Duval (who also went by the names Lemaire and Prosper) was likely born….around 1815–1820 to a black prostitute and a white father, and had performed in vaudevilles under the stage name Berthe in 1838 and 1839,” claims Colin Bailey in his review of “Posing Modernity” in The New York Review of Books. “She had been the photographer Félix Nadar’s lover before meeting Baudelaire in 1842.”

The poet may have first encountered her in a cabaret. “It seems that she was a ‘femme entretenue’—a kind of nineteenth-century call girl—who, prior to meeting Baudelaire, led the life of the ‘demi-monde’ so aptly described by Alexandre Dumas [whose grandmother was a Black slave],” writes Marc Christophe in the Journal of the College Language Association. The lovers both became seriously addicted to laudanum and alcohol, and Baudelaire constantly petitioned his mother for more funds to support a bohemian and peripatetic lifestyle. As Christophe admits, “It is not easy to determine who this Jeanne Duval really was. Even in Baudelaire’s opinion, she changes temperament and characteristics from one letter to the next [and] Baudelaire’s biographers hardly bothered to research, in depth, the poet’s attachment to the ‘Black Venus.’” In spite of complaints of mistreatment at her hands, however, the poet finds in her both “joy and tranquility.”

Yet by the late 1850s they seem to have parted for good. After Duval suffered a stroke in 1859, she “tried to extort money from Baudelaire,” Dolan claims. Three years later, Manet painted her portrait; and in 1865, the poet produced a little sketch of her as a voluptuous young woman with large dark eyes. Wikipedia says that Duval may have died of syphilis as early as 1862, five years before the poet, who also died of syphilis. But the photographer Nadar claimed to have last seen her in 1870, when she was on crutches.

So many mysteries remain. Why would Baudelaire sketch his lover as a young woman years after they parted? Why would Manet paint her when she was obviously frail and infirm? And capture her in a kind of costume that was most likely alien to her tastes and means (if you’re interested in crinolines and caricature, a truly fascinating discussion of this is in Dolan’s scholarly article, available here).

But the biggest gaps of all are in our knowledge of Duval herself: Did she have ambitions as a singer or an actress? Was she any good? Did she aspire to a more conventional life? Or could she have chosen a more favorable match than the scrawny and chronically impoverished Baudelaire? An exotic beauty in the Paris of her day, one suspects, could have done a whole lot better in the mistress department.

And why would she agree to model–raddled by infirmities, her glorious beauty long gone—for Manet after she’d broken off with the poet?

No letters or journals of Duval’s survive, to the best of my research, nor is there much in the way of testimony from Baudelaire’s friends and acquaintances. Her legend, though, has inspired novelists and artists to re-imagine her struggles. I’ve read only one, a rather tepid piece of historical fiction called Black Venus, by James MacManus, which fails to breathe life into this shadowy half of a love affair as stormy and steamy as this morning’s Hollywood gossip.

There are a couple more fictional accounts out there by the late English writer Angela Carter and Canadian-Jamaican novelist Nalo Hopkinson, which I will track down in due time.

My own take, after admittedly only two or three weeks of cursory investigation? She was dedicated to her abusive genius, but she probably gave as good as she got.

Love is strange.

Ann Landi

Top: Edouard Manet, Portrait of Jeanne Duval (1862), oil on canvas, 35.5 by 44.5 inches

`